By Alan Davidge

When the 230th Field Artillery Battalion was attached to the 30th Infantry (“Old Hickory”) Division in Mortain, France, on August 6, 1944, many of its men had already received their baptism of fire in Normandy. They had trudged through the grim remains of the slaughter on Omaha Beach, then endured weeks of fighting in the notorious hedgerows before arriving at the abattoir of St. Lô.

In addition to being on the receiving end of the worst that the German army could throw at them, a number of the “cannon cockers” had also been caught up in the short-bombing incidents by their own air force on July 24/25, which killed Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, the commanding general of Army Ground Forces, who was in France acting as a decoy as Commanding General of the fictitious FUSAG—the First United States Army Group (Lt. Gen. George S. Patton had played that role earlier).

This had taken place at the start of Operation Cobra, the breakout from the beachhead, which resulted in considerable American casualties. The 30th Infantry Division suffered particularly badly with many casualties coming from the 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment. These men thought they had seen it all: landing craft, mines, tanks, snipers, friendly fire and the dreaded 88s, but fate had more horrors in store.

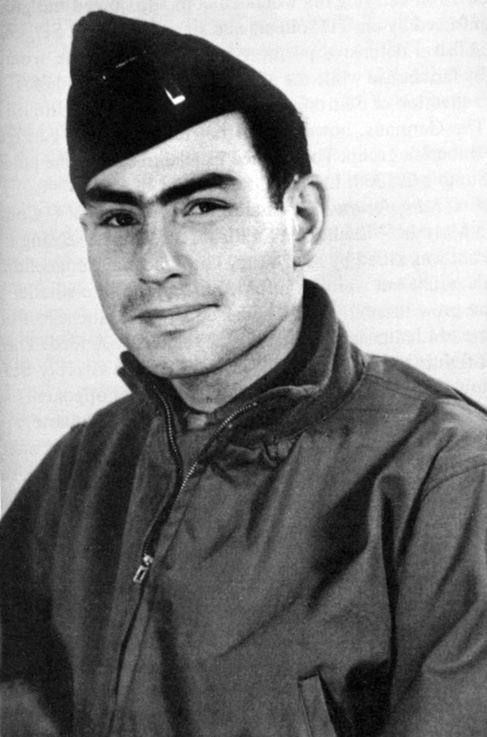

Private First Class Frank Denius from Austin, Texas, was one of the 230th FA’s Forward Artillery Observers (FAOs). After initial military training at school from age 13, he had joined the Army at 17 and was sent to The Citadel military training academy in South Carolina. After two semesters he was called up for active service.

Following the detailed preparation for the invasion, Denius landed at Omaha Beach on June 10, 1944, still six months short of his 20th birthday, where his first task was to support the 29th Division, whose first waves had been decimated on D-Day.

He was soon united with his attached division, the 30th Infantry and from there on it was combat all the way to St. Lô and Operation Cobra. In the process he earned his first Silver Star, taking over from his officer, a Lieutenant Miller, who had been gunned down beside him near St. Lô. A few days later, he found himself in a foxhole only 60 yards away from where General McNair died when an errant bomb fell into his foxhole.

To Denius’s relief, his battalion and the rest of the 30th Infantry Division was soon pulled out of the line for a rest, which included a United Services Organization show with the singer Dinah Shore and Hollywood actor Edward G. Robinson. To the envy of his mates, he also got a kiss on the cheek from Dinah Shore!

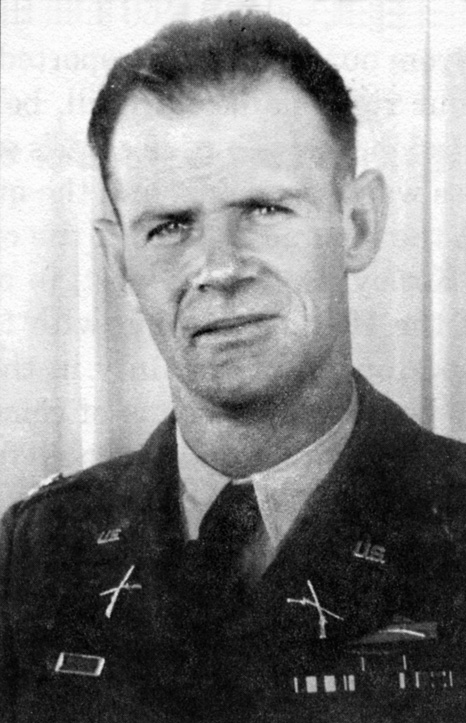

Lieutenant Robert Weiss from Indiana, another FAO with the 230th FA, had joined the Army in 1943 at the age of 20. Arriving on July 28 via Utah Beach, he was soon integrating himself within the 30th ID. At the same USO concert where Frank Denius was getting familiar with Dinah Shore, Weiss was detailed to be Edward G. Robinson’s driver, so they both arrived at Mortain on August 6 with name-dropping tales to tell. Their journey to Mortain through small French towns was equally memorable, with cheering crowds tossing bouquets of flowers and offering drinks to their liberators.

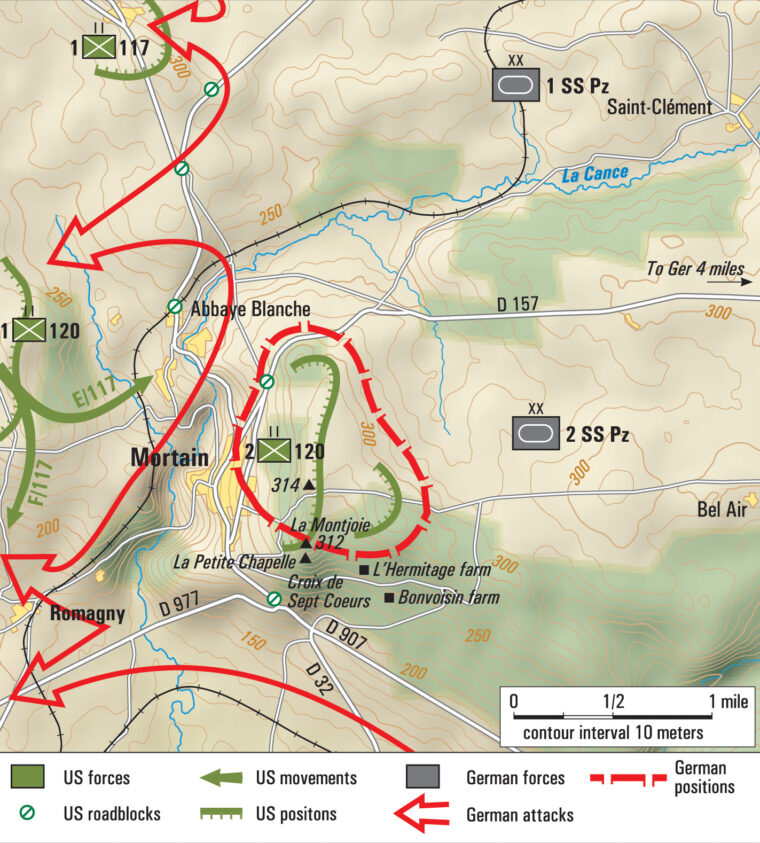

Leaving gun battery “B” of 105mm howitzers five miles outside of Mortain, Weiss drove with his team of three men into the town. Initially he met a Lieutenant Walsh of the 32nd Field Artillery, who was the Forward Observer of the unit that his battery was relieving. He then met his new artillery liaison officer, Lieutenant Webster R. Lee, who led them to Hill 314.

Previously occupied by German troops and more recently by the U.S. 18th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Infantry Division, the hill comprised a huge piece of craggy limestone overlooking the town, which was clearly a diamond in any army’s defensive strategy, dominating the landscape and offering views of up to 15 miles in several directions across the surrounding plains.

Mortain was quiet, a golden sun shone out of a pale sapphire sky, the 18th Infantry hadn’t seen a German for five days, and Patton was chasing the enemy out of France. On this hill you could see forever. What could possibly go wrong?

Denius, now a corporal, had been assigned to C Battery and was also up on the hill by early afternoon with his radio sergeant, Sid Goldstein, with whom he had shared his battle honors since his arrival in France, plus a commander of one of the companies of the 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment, who were already digging themselves into foxholes wherever there was sufficient depth of earth on top of the limestone.

Fortunately, as they were taking over from previous occupants, they were not starting from scratch, but their experience had already taught them the importance of a deep shelter and in this location, in the event of an attack, there would be splinters of rock and wood as well as shards of shell seeking a place to embed themselves.

They were also joined by a new officer to replace Lieutenant Miller, killed beside Denius three weeks earlier. Lieutenant Charles A. Bartz from Lincoln, Nebraska, was 24 and recently married, but his experience of combat was nil, so like all replacements he would have to discover very quickly how to put the theory he had learned into practice and follow the advice of those who had seen it all before. To those around him he was on a steep learning curve.

Writing about Bartz after the war, Robert Weiss said of him: “He always seemed to be looking over his shoulder and I could already see the pale stamp of death on his face. This gave me an uncomfortable feeling, and I could not look him in the eyes or study his face for long.”

The two teams of observers, on the advice of the departing 18th Infantry, and after discussion with their company commanders, chose the observation posts (OPs) where they would set up radios for their period on the hill. Weiss and his crew would occupy a high point on the east side of the hill, which gave a perfect view of the two main routes into Mortain: the road to the town of Ger (now the D157), and parallel to it on its south side, one they called the Bel Air Road, as it led to a small village bearing that name (now the D487). They also had a good view to the south.

Bartz, Denius, Goldstein and their driver, Louis Sberna, located themselves on the other side of Hill 314, facing west and looking down on Mortain itself and a little further towards the north, a location decorated with a series of rock outcrops that provided a fantastic view.

Denius and Bartz were able to explore the hill safely, out in the open on a clear summer’s afternoon and pre-register a series of points on roads and other crucial locations to call down artillery fire if necessary—a real luxury, considering the conditions under which artillery observers normally had to operate.

They worked out the coordinates of key places, allocated them a number as a reference for any artillery fire they may have to request, which would make the process quicker and simpler. On the Bel Air Road, and set between the two teams of observers, they discovered a farm, L’Hermitage, with a well and a pump that would be a great asset if the hot weather continued. They did, however, have sources on the hill from which they initially could draw water.

A number of companies from the 2nd Battalion took up positions on the hill while others stationed themselves in the town. Company K, under Lieutenant Joseph Reaser, located itself on the north of Hill 314 near the farm of Bonvoisin; G Company, under Lieutenant Ronal Woody, occupied a position further south but also spread out to the crags of Montjoie on the west (coincidentally “Montjoie” is an ancient French battle cry, shouted by warriors to hold the line).

H Company, essentially a heavy weapons unit, was down at the southern end. E Company, under Lieutenant Ralph Kerley, another proud Texan like Denius, was based in the east and south east which included the higher ground chosen by Weiss’ observer team. The hill was a vast feature, however, and significant distance separated the different units, which could make communications difficult.

After their eventual breakout from Normandy, U.S. troops did not expect a counterattack from the Germans. They saw the enemy finally losing its grip and felt they were already on the road to Berlin. Hitler’s decision, made four days previously on August 2 to reverse direction and try to push the Americans back to the coast at Avranches, would also have taken most German commanders by surprise.

His Operation Lüttich was a hastily conceived plan for a counterattack and despite the best efforts of Field Marshal Hans Günther Adolf Ferdinand von Kluge, whom he had placed in charge, there were delays and confusion among the Panzer divisions that would carry out the assault. The generals on the ground knew that it would not be possible to detach the eight divisions proposed by the Führer and position them for a counterattack within the time frame required, but planning proceeded.

The eventual line-up for the counterattack was: 2nd SS Panzer “Das Reich,” 2nd Panzer, 116th Panzer, and part of 1st SS Panzer Division “Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler,” plus some infantry divisions and other specialist groups and tanks.

General of Panzer Troops Hans von Funck was not optimistic of their chances and asked for a postponement of Lüttich, but without success. Hitler’s unwillingness to listen to his generals, who in turn were fast losing confidence in their Führer, had been a contributory factor to the unsuccessful assassination attempt which had taken place only a few weeks earlier and now he scarcely trusted anyone.

He had dealt mercilessly with the plotters (the “von Stauffenberg group”) and knew they still had sympathizers, so von Kluge and the other senior generals could not afford to raise his suspicions by questioning his plan, which privately they thought was crazy and unworkable.

The “Ultra” decoders at Bletchley Park in England picked up no clear warning of a counterattack but at 2 p.m. on August 6, while Weiss and Bartz were getting acquainted with Hill 314 in the summer sunshine, Panzer Division 2 broke radio silence and asked for nighttime air support in preparation for an attack.

This was followed by a specific reference to an attack on Mortain at 8:30 p.m., the contents of which were relayed immediately to Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, CG of 12th Army Group, and passed from him to American troops in the area. The scope of the attack soon became clear when a later message indicated the involvement of several Panzer divisions, followed by a further order to cut off supply lines and push American forces back to the coast.

The 30th Division records from 38 minutes after midnight on August 7 reported a possible enemy counterattack from the east or north within 12 hours, but this information arrived too late to reinforce the 120th Infantry. By 4 a.m. on August 7, the Americans had a complete picture of the plan, had already felt the first shells being directed at them, and realized that the odds were heavily stacked in Hitler’s favor.

While the generals were considering how to react to the first indications of a counterattack, the FAOs on Hill 314 were ahead of the game. What the two teams started to observe that afternoon had not suggested an enemy in retreat. They were also perturbed by a single German aircraft that appeared at 2:30 p.m. and seemed to be undertaking a reconnaissance of their position.

By 4 p.m., when everyone was set up and well camouflaged, Weiss’s top non-com, Staff Sgt. John Corn, began scanning the landscape to the east with the BC scope, the artillery observer’s weapon of choice to seek out the enemy. A trusty but heavy piece of kit, the BC (short for Battery Commander’s) required a tripod for accurate reading. Close by was the equally cumbersome but utterly essential Model 610 radio, weighing in at 35 lbs. and fitted to a battery pack of similar weight.

Corn called his lieutenant over to share what he saw. A company of German soldiers was marching along the road towards them, just over a mile to the east and already disturbingly close to the infantry’s front lines.

A primary role of the FAO is to protect the infantry to which it is attached, and Weiss knew exactly what to do. He called an order to Sergeant Sasser, his radio operator: “Fire Mission!” It was his first real shoot since joining the team—he would call another 192 over the next six days and nights. Each call with its data and coordinates would be transmitted to a Fire Direction Center for further calculations and a command sent to the appropriate battery to hit the target.

The commander of this crucial unit was Lt. Col. Lewis D. Vieman, yet another Texan, whose three-word reply, “On the way,” would become a mantra to the artillery observers on Hill 314 over the next few days. (Frank Denius chose it over 50 years later when he was searching for a title for his autobiography.)

Given the number of Texans on this hill, soon to be surrounded on all sides, they could have easily felt that history was repeating itself, but their radios would ensure a better chance of survival than their forefathers at the Alamo a century before!

The first of Weiss’s shells burst close to their target and, as he had been trained to do, he made an adjustment and sent it through to strike a closer blow. When the dust cleared after the second salvo, there were no signs of German life.

It soon became clear that the enemy was going to use every weapon at its disposal to dislodge the infantry on Hill 314. Shortly after the first incident, the message log records six German Focke-Wulf 190s flying over the hill and explosions were heard to the north as bombing commenced.

Then the troops on the south east side were subjected to a mortar attack. The observers hit back after some intelligent guesswork. They saw the direction of fire and knew the mortars had a range of barely a mile, so that was their target. Then, shortly before dark, a runner arrived with further sightings of German uniforms in the distance. Another phone call and more artillery shells were on their way.

A temporary sense of normality then prevailed as hot food arrived, together with an allocation of D and K rations, plus a field telephone which allowed Weiss to speak to Lieutenant Lee, the artillery liaison officer who was back in Mortain after showing them around the hill. Lee provided Weiss with a nighttime plan for defensive artillery fire, just in case.

Not long afterwards, German troops stealthily occupied Mortain, captured Lee, and the line went dead. The hill was starting to become a lonely place. The Americans who had taken up defensive positions were soon reminded that they were among friends, as some of the French had remained and knew the local geography well enough to pass on valuable observations. The message log for the latter part of the day records a French civilian reporting enemy 75mm guns on high ground and, at 8:45 p.m., another brought in another sighting of a German gun battery.

The first attacks of the night manifested themselves south of Hill 314 at the Croix de Sept Coeurs (Cross of Seven Hearts) road block and at l’Abbaye Blanche (the White Abbey) north of the town. The southerly roadblock was overrun and a fierce attack was launched on the roadblock beside the abbey. The men stationed there held firm but could not prevent some Germans from entering Mortain.

On the west side of the hill, occupied by Denius, Bartz, and G and K Companies of the 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment, there was a penetration just after 1 a.m. by SS troops screaming “Heil Hitler!” Denius had to lie on his radio to deaden its sound as it would have become an immediate target for their attackers.

A brand-new, air-cooled .30-caliber machine gun set up by an infantry team immediately jammed, resulting in desperate hand to hand fighting with the Germans tossing “potato-masher” grenades at them until the invaders were finally expelled. With the enemy literally on top of them in the middle of the night, the observers’ specialist skills were of no use. They could only pick up the nearest weapon and fight for survival alongside their infantry comrades and wait for daylight to present them with a target they were trained for.

After the initial attack, the Bartz team moved further north to a location close to Lieutenant Reaser’s K Company command post for better communication as Reaser had set up listening posts around its perimeter. This was a spot proposed initially by Denius but he had been overruled. Bartz instead had chosen an area on the west side of the hill where he, Denius, and Goldstein could share a foxhole and set up a radio.

But Bartz deferred to Denius now and their trek in the dark became a difficult one, especially given the burden of their 510 Signal Corps Radio (SCR) weighing 75 lbs. which they had to carry between them.

An hour after the western attack from Mortain, K Company had to deal with a second incursion from the north. This was most likely the group of Germans that had managed to squeeze past the otherwise effective road block at l’Abbaye Blanche.

To the south of the hill, some of the H Company positions were also overrun in the dark, losing much of their hardware, jeeps, and an 57mm anti-tank gun, prompting the survivors to withdraw and join up with units elsewhere. A number of them stayed with Lieutenant Kerley on the southeast side, bringing their remaining weaponry with them.

Locating the enemy by sound only, Weiss had to call down artillery fire to beat off the attackers. This was a risky business, but fortunately none of it came close enough to cause casualties among American troops. The men had suffered enough friendly fire already in Normandy.

The dawn of August 7 brought with it a mist and low cloud which incapacitated friend and foe alike, although the troops on the hill suspected it was a deliberate smoke barrage. The loss of a telephone line made matters worse and company commanders had to rely on runners.

One of the most important functions of the runners was to update the observers on where the enemy was threatening the other units so that they could call on artillery fire for protection. The infantry did possess field radios but their range was limited and their clarity was poor.

Weiss relocated his OP on the east ridge to Kerley’s E Company command post in the shelter of a draw to the southeast. One runner then arrived with details of several hundred enemy troops massing for an attack, but a well-targeted radio call and subsequent barrage soon scattered them.

As the visibility improved, Weiss and one of his team reoccupied the crest of the east ridge and called down artillery fire on anything that showed its face. He sent the other two in search of extra radio batteries, realizing the crucial role his radio was going to play in the defense of the hill. They soon became targets themselves from speculative machine gun fire from an enemy already familiar with the terrain.

More worrying was the sniping from the rear, suggesting that the Germans had gained a foothold on the southwest side. It later became clear that they had occupied the area around La Petite Chapelle on an outcrop of rock, a local beauty spot which also provided an excellent viewpoint.

The other team, now firmly entrenched in K Company’s area also made the most of the sitting targets below. In his autobiography, Denius states, “While Lieutenant Weiss called in artillery on the east and southeast, I called it for the south and southwest. We laid a solid ring of fire on them. Their casualties and vehicle damage were incredible. The few undamaged German vehicles withdrew to the east, loaded with men fleeing from a killing ground.”

At this stage, the Germans were unaware that the American artillery observers had them in their sights and the appearance of their uniforms attracted one hail of shells after another. They gathered for another attack up the steep slopes from Mortain around 2 p.m. but were driven back down the hill by accurate artillery fire. This was fast becoming the only real resource available to the Yanks. Infantry ammunition was getting dangerously low and, as the last of the D rations were consumed, the men were in danger of losing their physical strength.

E Company’s command post moved to the cliffs on the south side of Hill 314, effectively its highest point, and the observers followed. Its value in commanding the fields and roads to the south was immediately apparent, providing a choice of several slowly moving targets below. Boots or wheels, they couldn’t get away fast enough. Weiss greedily devoured everything with his fire mission calls.

By the afternoon, the enemy had become much more circumspect in his incursions, a double success for the artillery. That which it hadn’t destroyed was extremely cautious and forced to slow down. New tactics would now be necessary to dislodge the hill’s defenders.

The Americans were soon pinned down by a sniper who had managed to infiltrate their lines and Kerley, always leading from the front (he was later to be awarded the DSC for his leadership), seized a rifle and disappeared into the undergrowth. An anxious wait, then two shots. Another wait and to everyone’s relief, it was Kerley who emerged from the woods.

The company and observer team then came under fire from an 88mm gun some distance away, causing infantry casualties and snapping the top off Weiss’ radio antenna. Next it was the observer’s turn for a narrow escape when an 88 shell bounced off an outcrop next to him and exploded harmlessly among the rocks below.

Weiss subsequently calculated the co-ordinates to silence one of the 88s but others still managed to penetrate the east side of the hill, as did the enemy’s tanks and infantry. Snipers from behind also continued to test their nerve. At one point his message log states, “Enemy north, south, east, and west.”

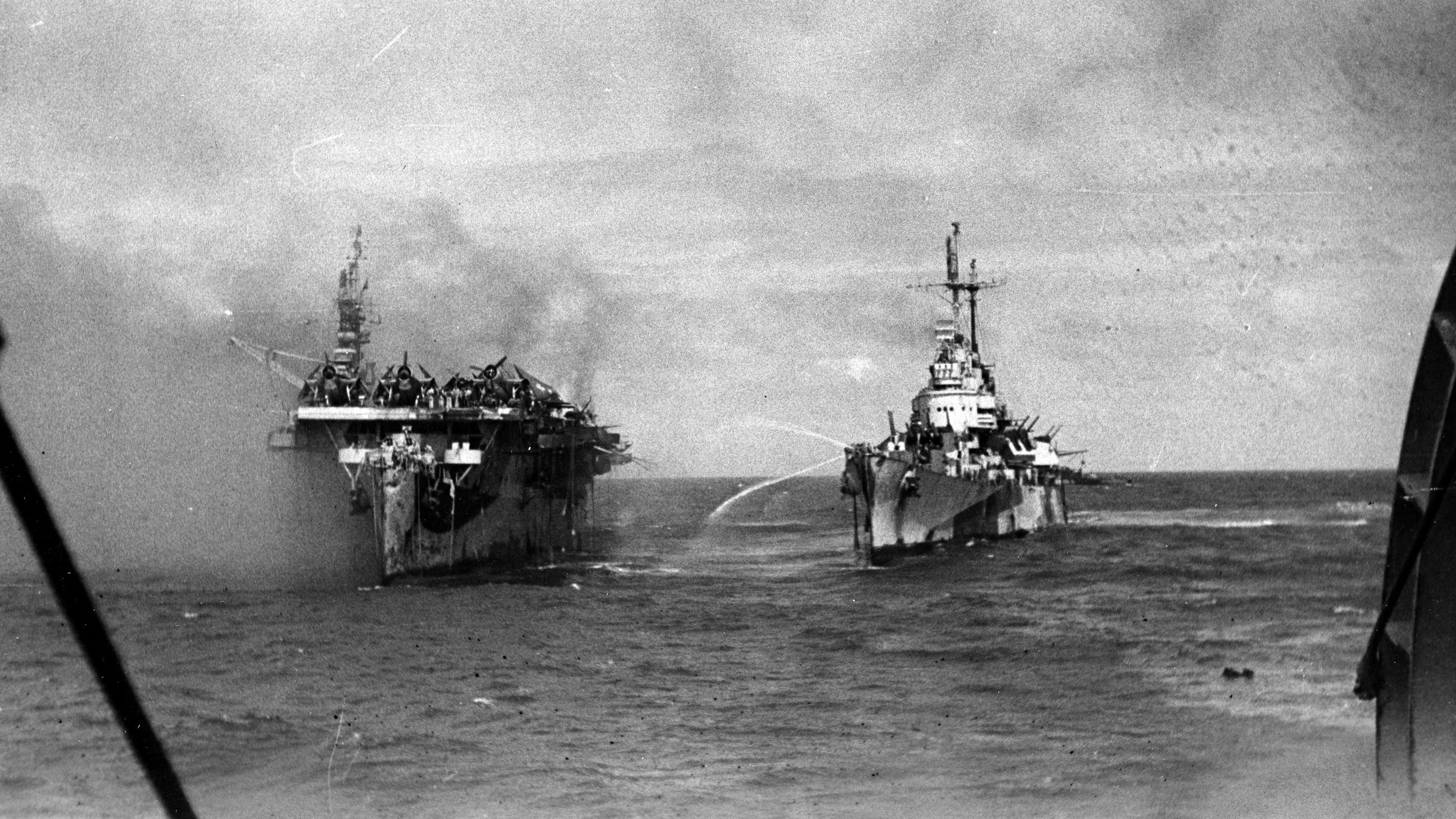

Although it was impossible at this time to get reinforcements through to Hill 314, they did receive support from the skies. On August 7, Denius stated in his autobiography that American fighter planes flew 429 sorties over German forces in the area, which kept the Luftwaffe busy, and RAF Typhoons unleashed over 2,000 rockets at German tanks and vehicles. However, despite all this support, the battalion suffered a reported 78 casualties that day.

Having no idea what the night would bring, Weiss devised a protective strategy. He would fire a regular barrage, then adjust it to bring it as close as was safely possible to his own company’s lines. In the event of a night attack, he could then recall this concentration to defend their position. Reports were also coming in from French civilians, identifying movement of German troops, and at 10:30 p.m. they informed the observers of 100 German tanks that were gathered in Romagny, a small town to the south west of Mortain.

batteries.

Company commander Kerley set up a series of listening posts around his perimeter as an early warning system and then dictated a message to say that ammunition was running seriously low. If the Germans had known the dire straits the battalion was in, they could have overrun the hill, but their dismemberment by the artillery that day whenever they moved into the open had made them extremely cautious.

Everyone in Mortain had also been taken by surprise the previous night and early morning and now the confusion continued. An Oberscharführer from the 17th SS described what he saw: “The houses had been abandoned by the people. Around 300 old people were gathered in a retirement home. The town’s inhabitants had celebrated their liberation with the Americans that evening—food and drink was still on the tables. Some comrades feasted on it before they thought about further searches through homes. All houses were covered in flags. Nobody expected our attack. The town was abandoned in panic and fear.”

American troops were outnumbered and a game of cat and mouse ensued. Lt. Col. Eads Hardaway, the battalion commander, had set up his HQ at the Hôtel de la Poste in the town’s center and could not extricate himself. So Captain Reynold Erichson of F Company, the most senior company commander, was directed through a radio call from Colonel Hammond Birks, commander of the 120th Infantry Regiment, to take charge of the remains of the battalion on the hill.

In practice, communication problems would mean that the management of each company was down to their individual commanders who selected the best-protected positions and held on to them. An overall strategy for defending the hill would not be easy. As well as K, G and E Companies, which occupied discrete but separate areas, there was now a platoon from C, a squad from F, plus survivors of H Company and the remains of a tank-destroyer unit. Erichson decided to position himself on the northern half of the hill near Bonvoisin farm and hoped that with limited radio contact and a system of runners, he could keep these disparate groups functioning.

On the east side of the hill, the careful listening paid dividends. At 2 a.m. on the morning of the next day, August 8, the unmistakable sounds of tanks drifted up from the Bel Air Road in an area previously registered for artillery fire. The next sound was Weiss on the radio, followed by shells exploding among the tanks. The Germans must have figured that their enemy could see in the dark!

Behind Kerley, Weiss and his crew with G Company on the west side decided to cross the Bel Air road and move further north, close to K Company, but there was a problem. When the west side of the hill came under sustained fire the first night, it was Lieutenant Charles Bartz’s first real combat experience. Denius had been concerned about his nervousness and that when he tried to engage him in conversation, his replies did not make sense.

By early morning Bartz told Denius he couldn’t cope and retreated to a foxhole. Despite being still only 19, young Frank took charge, ably assisted by his buddy Sid Goldstein and called in artillery fire as required, just as he had done when his previous officer, Lieutenant Miller, had been shot down beside him three weeks earlier.

Shortly after dawn that morning, enemy vehicles broke through a roadblock before being literally stopped in their tracks. Already it was apparent, however, that the radio batteries were not going to last much longer; Denius hit upon the idea of leaving them out in the sunlight to collect some extra charge. This only gave them about an extra six minutes each time, but it enabled contact with the Fire Direction Center at crucial moments. Weiss lost contact with Denius at this time and believed for many years that the batteries had expired, putting an even greater responsibility on his shoulders.

Operation Lüttich was now into its second day and its commanders were realizing that a major obstacle to its ambitious aim of pushing thousands of Americans into the sea at Avranches and splitting their armies was the few hundred troops who occupied a hill at Mortain and who had them in their sights—and were pouring all manner of Hell down upon them. If they could take the hill, they would not only be helping themselves to one of the best vantage points for miles around but also removing the threat from the showers of artillery shells being directed upon them by the forward observers.

The 2nd Battalion may have been running short of resources to defend its position but its real ammunition was the plentiful supply of 105mm howitzer shells that could be commanded from the sky by the forward observers to litter the roads and fields with burnt-out German tanks and wounded men at a moment’s notice.

At 8 a.m., German troops were seen from the east side to be assembling for an attack. A radio call, followed by “On the way,” and they were gone. Then the tanks lined up and suffered the same fate. Next, an 88 was silenced as soon as its voice was located. The summer sunshine and excellent visibility meant Weiss and his men were on a turkey shoot.

But the lieutenant was running short of juice in his radio batteries, and the water was almost gone. K rations would not suffice for long, either. Increasingly, valuable radio time was being used to plead for more supplies. Some of the troops closer to the road and G Company’s position were able to get water from the well at l’Hermitage farm. but German snipers made access feel like a game of Russian roulette.

Enemy gunners were now varying their tactics. Armor-piercing rounds were hitting the rocks and sending out showers of splinters onto the men below. Next it was phosphorous shells dropping white-hot flakes that caused painful burns and which took a serious toll on morale.

Spirits were lifted when a group of British Typhoon fighter bombers appeared, flew low, and obliterated more tanks and guns. It was the batteries of 88s that were causing the greatest grief, however, and Weiss took the risk of climbing to the top of the highest crags, deliberately exposing himself to enemy fire in order to get a better view. He was hoping he was too small a target for an 88 shell, although his former radio antenna may have disagreed. When they started up again he was able to fix their positions, albeit with several adjustments, and put some of them out of action.

By evening the occupants of the hill were hit by something even bigger. Intelligence gained from a captured German the day before revealed a gun battery near Ger, about six miles to the northeast. This was probably the source and likely to contain 150mm guns. It was beyond the range of the 230th Field Artillery, but the location was estimated and details were passed on in the hope that the air force or the American 155mm guns located further away could take care of it.

Something that Weiss and his team could do was to keep an eye on the roads below their hilltop position and sure enough before midnight there was an attempt to overrun the 30th Division roadblocks by enemy tanks. Both the Ger and Bel Air roads to the east, and the dirt tracks that separated these parallel routes, saw significant tank activity. Three times they tried to attack and three times—thanks to the skill of the listeners and the prearranged fire plans—they were pushed back.

Then the German infantry behind them in the southwest, who had been sniping during the day, made an opportunistic attack in the dark, firing blindly and randomly with an apparently inexhaustible supply of automatic rifle rounds: these only claimed a small number of victims but greatly unnerved everyone on the east side of the hill. The best they could do in return with their sparse ammunition was to try and pick off the source of the last muzzle flash.

The next day, August 9, Weiss and his team moved to a third and final OP on the top of the east ridge, and the day followed the same familiar pattern. Five attacks had to be beaten off before 9 a.m. And still they came. The climax was a huge convoy of German infantry trucks in early afternoon. When they unloaded their men, they received an enhanced concentration of shells from the Fire Direction Center; 24 105mm howitzers, supplemented by a 155mm battery, tore the intended attack apart before it got started.

While some men resorted to scraping slivers of chocolate from their D rations with a bayonet to quell their hunger, others went out scavenging food from local farms and returned with potatoes, cabbages, rutabaga and apples. Some were very fortunate, receiving rabbit and chicken soup from the few French farmers who remained and who were prepared to risk retribution from the SS.

(It should be remembered that one of the divisions present was “Das Reich,” which had committed the atrocities at Oradour sur Glane on June 10, where a whole village was massacred). Local French historians have recorded the contributions to the defense of the hill made by local French civilians who had been isolated along with the 2nd Battalion. Some of them were locals and others were simply taking refuge from the shelling as the front line moved eastwards.

Mr. and Mrs. Laisné pumped water for the men who could avoid the sniper fire to fill their comrades’ canteens and their efforts were supplemented by Mrs. Veuve Baudin and her young son. Elsewhere, Mrs. Lévêque and her daughters, Philomène Malherbe and Veuve Sineux, prepared soup and risked everything to support their liberators. Most of these women were enduring the war on their own, as their husbands had been captured in 1940 when France signed the armistice with Germany.

Shortly after 6 p.m., two Germans were seen in the distance—an SS officer, and a soldier holding a white flag. One of Kerley’s platoon officers raced to meet them before they got close enough for their eyes to absorb anything of importance.

The SS officer spoke in perfect English, congratulating the troops on their heroic defense and offering honorable surrender terms and treatment for the wounded. They had until eight o’clock to accept but, if they refused, they would be blown to bits. The officer relayed the surrender offer to Kerley. His reply was recorded in some sources like an extract from an historical novel, stating that they would not surrender until the last bullet had been fired and the last bayonet broken in a German belly.

Kerley was not given to flowery language however and the general agreement from those present was that he simply told the bilingual officer “Go f**k yourself” Eyewitness accounts also confirm that many of the wounded within earshot also voiced their support for Kerley in spite of their injuries.

The deadline passed and everyone took up defensive positions. Weiss agreed on a fire plan as he had done before, considering the most likely directions from which the attack would take place. In all, there were seven artillery battalions in place which set up a protective ring of fire around troops on the hill. The post-battle report states, “We all slept with hands on our guns, ready for a final fight.”

When it began, they found they were fighting tanks rather than infantry, a slightly less elusive target, and the artillery was able to hold them back until one tank managed to get though the roadblock and fire a couple of rounds.

The turret opened and the commander called out another “Surrender or die” threat, receiving a Kerley-esque response from most of those within earshot although one American soldier dropped his rifle, ran to the tank and clambered aboard. His apparent loss of nerve may have done his comrades a favor as it seemed to satisfy the tank commander who turned his vehicle around and left the hill.

The next day, August 10, and Day Five on Hill 314, began hopefully with the enemy apparently moving in the opposite direction, something noticed by both Weiss and Denius on their opposite sides. But far from being a retreat, it proved to be just a repositioning for a change of tactics. The fire missions continued but battery life became even more critical, and Weiss’ corporal Dan Garrot managed to retrieve a spare pair from their jeep that had been concealed some distance away.

Radio operator Armon Sasser then developed a useful technique, putting one pack in the sunshine to absorb heat, which generated some power, and rotating them with the other set but never letting one completely run out so that it was beyond the point of no return. For the night session, they tried to ensure that both had a reserve of power.

After their frantic calls for extra supplies, spirits were lifted in the afternoon by a parachute drop. First came a Typhoon raid on enemy positions and tanks, then, half an hour later, the aircraft appeared again as escorts for cargo planes which dropped a multitude of orange and blue parachutes over Hill 314. Unfortunately, many drifted into enemy lines; those that were retrieved, despite containing valuable food and ammunition, did not provide batteries or medical supplies.

Later that evening, an attempt was made to lob in medical supplies via artillery shells. Denius received a call from his the artillery battery to say they had shells that were used for propaganda leaflets which were going to be emptied and filled with medical supplies. As they were not designed to explode, they should arrive intact.

Denius and Weiss, in their separate accounts of the event welcomed the initiative at a time when their comrades were dying before their very eyes but, unfortunately, they were working against the laws of physics. The contents of some of the shells were destroyed in transit or even as a result of the exit from the gun barrels due to the tremendous forces involved, and the bandages were hopelessly compressed within the shell casings.

On Denius’s side of the hill, he personally directed the shells that would bear distinct markings, into a position where they could be dug out of the ground and, although the contents were not in great shape, he remembered that they managed to get enough morphine and penicillin to put a smile on the faces of the wounded.

The best protective care that could be achieved for the wounded was to put them in slit trenches or shield them against hedgerows out of the way of shell fragments. The dead, both American and German, were placed out of sight of their comrades, but the summer heat reminded veryone that they were surrounded by death and corruption. Morale was being stretched to its limits.

A further attempt was made on the morning of August 11 to send more supply shells, but with limited success. The only certainty was more panzers, more soldiers, more fire missions, and more carnage.

That morning, Denius heard heavy firing from behind the lines and could see signs of the enemy withdrawing. As well as suffering his artillery strikes from radio batteries that were now breathing their last, the Germans were also becoming targets for the air force. He reported, “The view from Hill 314 gave us ringside seats to this horrible spectacle that the Germans had brought upon themselves.”

Toward the end of the afternoon, there was an assault from a heavy mortar which forced Weiss and his closest comrades to take cover. It became apparent that the excitement about the medical shells had brought many men out into the open and suggested a likely target to the enemy.

When Kerley realised what was happening he, typically, went in search of the perpetrators, taking a mortar man with him. Once located, he ordered their 60mm mortar to be carried across for some retaliation. Unfortunately, there was only one round left. The preparation took an eternity for precision to be achieved but when the projectile was launched, it landed within 10 meters of the enemy mortar. Those team members who were able to stagger away did so immediately and the threat was curtailed.

From the west side of the hill, Denius witnessed further devastation: “When night came, their foot soldiers began walking out and they too were cut down by artillery fire that plastered their routes of withdrawal using the preregistered firing instructions our forward observer teams had provided.”

During the night of August 11/12, Weiss was still firing at tanks, relying largely on sound as a guide to the enemy’s position. Around 5 a.m. he left his foxhole to observe the enemy as it was clear that they were now retreating, but he knew they could still be dangerous. This decision saved his life.

The foxhole he had just left was hit by a shell, mortally wounding Staff Sgt. John Corn and dazing the rest of the team. With what was left of their radio batteries they continued calling down fire on the retreating tanks and trucks and made a desperate but futile attempt to get medical help for the dying Corn. The last of Weiss’s 193 calls to the artillery was made just before midday.

Elements of the 35th Division had now moved up to Mortain and were poised to relieve the men on the hill with much needed supplies. The first to arrive were troops from the 320th Infantry who entered G Company’s area at 11:30 a.m. The 1st Battalion, 119th Regiment, of the 30th Division itself marched through the town and relieved K and E Companies. The wounded were evacuated and food was distributed. Of the 690 men who had occupied Hill 314 on the afternoon of August 6, 277 were killed, missing or taken prisoner.

When Denius walked off Hill 314, he had one more unpleasant task to undertake. For six days and nights he had taken charge of his team in place of Lieutenant Bartz, who had been in no shape mentally to perform the duties required of him, a situation which could not be allowed to continue without putting lives in jeopardy.

He asked to see his battery commander, Captain Merrill Alexander, and told him the full story. The result was that a court-martial was arranged for Bartz to answer the charges against him. But while he was being escorted in a jeep by two military policemen, the vehicle was strafed by a German plane, killing its occupants, and seriously wounding Bartz. He was taken to a hospital in England, where he died of his injuries on October 31.

This was a double tragedy for the family. He left a young wife who never remarried and his mother lost her other son, an airman, the following year. It will never be known whether he was suffering from a condition that should have been picked up before he was sent into action or whether he was simply guilty of dereliction of duty. The court-martial did not take place and—innocent until proven guilty—he received a military funeral and a posthumous Silver Star for his role on Hill 314.

The men who staggered down its slopes would take indelible memories of those six days and nights with them to their next date with destiny. One of them, a certain J.D. Salinger, would become one of America’s most celebrated writers. Several others would receive gallantry decorations, some posthumously, and a great number of survivors would wear a Purple Heart decoration on their chests with pride to remind them of their service on Hill 314.

The valuable time that the Germans wasted trying to capture Hill 314 cost them dearly, providing an opportunity for the Allies to race eastwards and carefully position themselves to encircle and destroy the retreating army near Falaise.

Stories of Hill 314 and what later became known in the literature as “The Lost Battalion” which occupied it August 6-12, 1944, continue to plant themselves in posterity. The wall of the mayor’s office in Mortain bears a huge poster from the 40th anniversary in 1984, signed by many veterans, including Robert Weiss, who returned for the commemorations.

Weiss and Denius have made other visits and both wrote autobiographical accounts of their experiences, published in 1998 and 2016, respectively. In 2011, director Lew Adams, largely inspired by Frank Denius, completed a documentary film “Heroes of Old Hickory,” partly shot in the town with aging super-heroes reliving their youth in open-topped jeeps, driven through the streets of Mortain, and once again being cheered and fêted by the people whose town they liberated.

Then, in July 2020, the 30th Infantry Division was finally awarded the Presidential Unit Citation after several well-publicized campaigns and veterans were honored at a celebration in Raleigh, North Carolina. One of those present, Tony Jaber, who was a mortar gunner assigned to Company E under Lieutenant Kerley, summed up his feelings: “I wondered if we’d ever get rescued, but I didn’t think that I’d ever get killed up there. We had a company commander who wouldn’t surrender, so we were lucky.”

The signs in Mortain point upwards to Côte 314, but today it is a hill of two halves. An easily accessible footpath on the west side overlooking the town runs through the rocks of Montjoie, and the visitor is directed to some of the points where the action took place, by thoughtful signage thanks to the local French landowner.

A 10-minute walk from there, past the Hermitage farm on the Bel Air road, leads to the forest track down which Weiss was driven on August 6. This east side of the hill is now a hunting reserve and privately owned, an area of woodland so dense and overgrown that it seems as if Pan, the Greek god of forests, has reclaimed it for himself.

It even presented problems for Robert Weiss when he last visited Mortain in 1994 in an attempt to retrace his steps. In his account, Fire Mission!: The Siege at Mortain, he found little that bore any real resemblance to the bare, rocky ridges that earned him a place in history.

In a wooded depression which he felt bore the closest resemblance to the place where he said his farewells to Sergeant John Corn, he saluted his missing comrades for the last time and left his memories to rest in peace.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments