By Ron Gilliam

On the morning of May 15, 1942, a strange motorcade rolled out of Campo Four, located 170 hot, dusty miles south of the Italian base at Jalo oasis in northeast Libya. In accordance with the rules of war, the two Canadian Ford station wagons and two trucks captured from South African forces sported the German Balkenkreuz (straight cross) and Afrika Korps 21st Panzer Division palm tree stencils, partly rubbed out and sprayed with dust, however, and barely visible in the camouflage paint scheme.

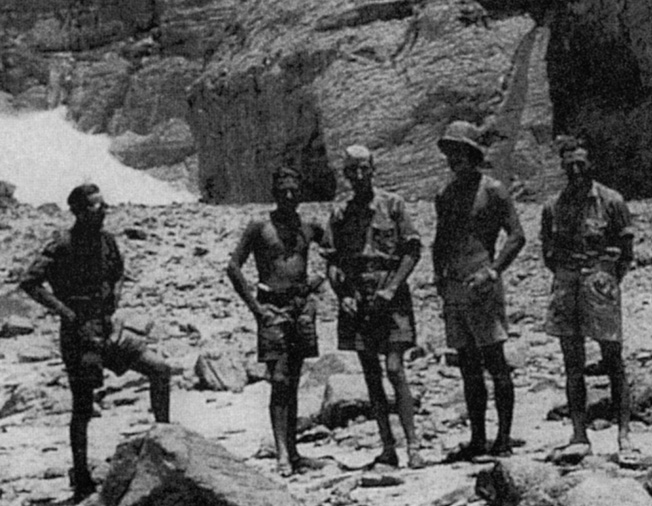

The six passengers were in nondescript khaki shorts and shirt uniforms with unobtrusive insignia, the minimum to avoid being shot out of hand as spies. Their mission was clandestine rather than covert. For the next three weeks, they would hide in plain sight, concealed in the vastness of the greatest desert on the planet, the Sahara.

Reed Thin and Desert Tough

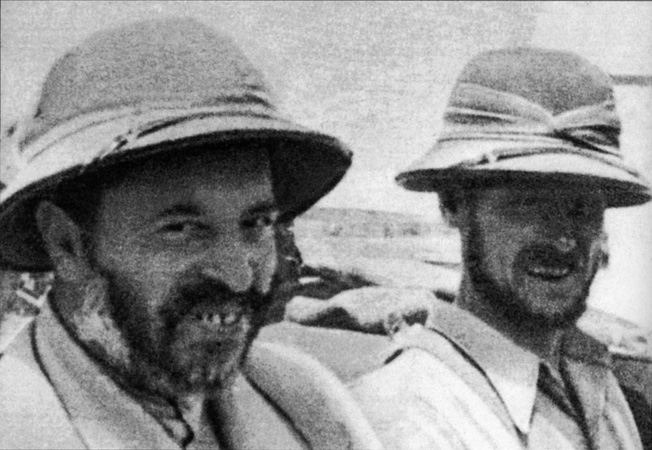

Driving the lead vehicle, a small tricolor fluttering from its whip antenna in deference to Italian theater command, was the mission leader, Hauptmann Graf (Captain Count) Ladislaus Eduoard de Almasy, Royal Hungarian Air Force, seconded to the German Abwehr (Foreign Intelligence). Medium in height and slightly stooped, reed thin and desert tough, the 47-year-old Almasy had lived in Egypt 13 years before the war, and was a published desert explorer, mobility expert, and celebrated aerial discoverer of the Lost Oasis of Zerzura.

Fifty years later, Almasy would acquire posthumous celebrity of another sort as the title character in the 1992 novel and 1996 Academy Award-winning film The English Patient starring Ralph Fiennes.

Unbekannte Sahara: Almasy’s Memoir

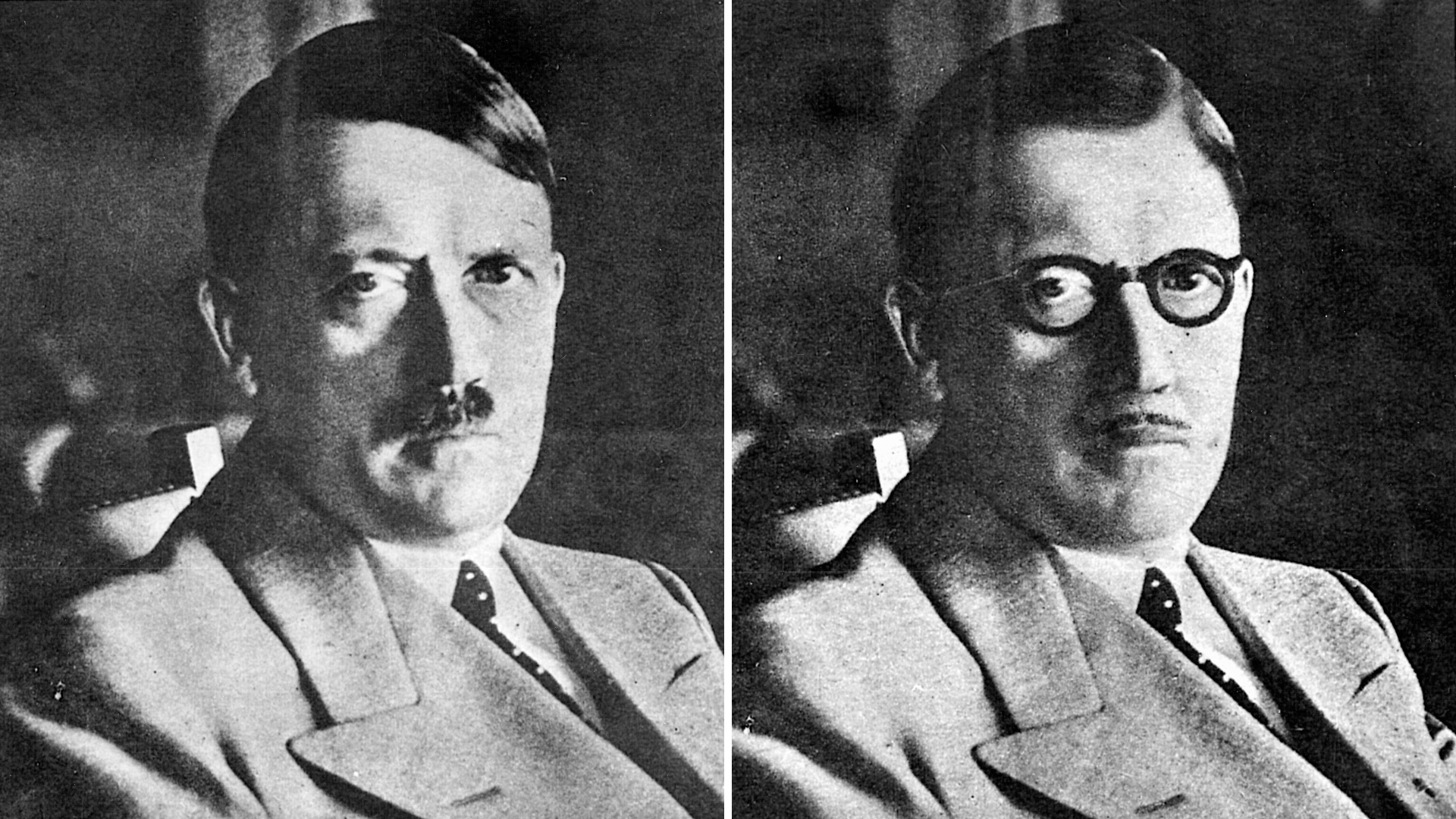

Almasy’s Abwehr assignment resulted directly from the 1939 German publication of his memoir, Unbekannte Sahara: mit Flugzeug und Auto in der Libyschen Wüste (Unknown Sahara: With Airplane and Automobile in the Libyan Desert). Impressed by it, Major Franz Seubert, North Africa desk chief, asked Major Nikolaus Ritter to check out its author on his next trip to Budapest. Ritter, a 42-year-old Abwehr veteran, had scored a major coup during his 10 years in the United States when one of his spies copied blueprints of the Norden bombsight and now directed all espionage operations against Britain and the United States.

When Almasy mentioned his acquaintance with Egyptian General Aziz el Masri, an Arab nationalist whom the British had ousted as Army chief of staff, Ritter conceived “the fantastic idea, crazy but possible,” as he put it in his postwar memoir, of inducing the general to defect to Germany and organize an Army revolt against the British. Almasy, he noted to his surprise, “was absolutely sure it could be done, although his own desire to get back into Egypt may have fostered his conviction.” In January 1941, after Adolf Hitler decided to pull his Italian mentor Benito Mussolini’s imperial chestnuts out of the North African fire, Ritter’s “fantastic idea” became Plan El Masri. While Field Marshal Erwin Rommel organized an Afrika Korps, Abwehr chief, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, handed Ritter a long-desired field assignment: form a Sonderkommando with Almasy “working not for Rommel but with him” to undertake spectacular enterprises, specifically to get el Masri out of Cairo and into German hands, to infiltrate Abwehr agents into Egypt, and to “assist IC [intelligence officer] Afrika Korps through Almasy on conditions in the desert and in Egypt.”

Back to the Desert That “Captured” Him

Now Almasy had a ticket back to the desert, which, he wrote in 1929, had “captured” him. But it was a Faustian bargain. Never questioning the traditional royalist political views of the lower nobility into which he was born, Almasy instinctively disdained fascists. He had even worked to restore the exiled Hapsburg emperor to his Hungarian throne in 1921,receiving the (unconfirmed) title of “count” from the grateful but frustrated monarch. Still, he had an officer’s duty to his country, whose Axis-leaning government had early in 1940 recalled him from the World War I reserve list as a flight instructor (and probably intelligence officer) and would formally become Germany’s ally in November.

A friend asked how he could reconcile working for the Germans with his friendship for the British: English boarding school, cofounding the informal “Zerzura Club” of British explorers in a Greek bar in Wadi Halfa in 1931, and even confidentially offering his desert expertise in 1939 to the British Army. Almasy replied warily that he would do nothing not in accordance with military honor. After top-level arrangements, he was seconded to the German Abwehr and assigned to Aufklärungskommando Nordost Afrika (Reconnaissance Command, Northeast Africa), Sonderkommando Ritter, as 2IC (2nd intelligence officer).

Reporting to the 10th Air Corps

In March 1941, Almasy and Ritter reported to X Fliegerkorps (10th Air Corps) in Taormina, Sicily, their logistical and administrative home. General Stefan Geisler, the commander, assigned them a Fieseler Fi-156 Storch liaison plane and two pilots and authorized them to borrow two Heinkel He-111 medium bombers from Kampfgeschwader (Bomb Wing) 26 for long-distance missions. He also authorized Almasy to wear the uniform of a Luftwaffe captain, to avoid awkward questions, German or, in case of capture, British.

Ritter had brought along four radio operators from Lehrregiment (Training Regiment) Brandenburg, a shadowy outfit created to provide the Abwehr with bilingual personnel for operations behind enemy lines. They would set up radio-relay stations at Taormina, Athens, Greece, and in Libya at headquarters Afrika Korps, and in the field. The Sonderkommando flew to Tripoli in April and drove to Rommel’s headquarters at Derna, 1,000 miles east along the coastal Via Balbia. Ritter flew ahead to coordinate the escape plan with General el Masri via a clandestine radio in the Hungarian legation in Cairo.

Crash-Landing 10 Miles Outside of Cairo

On the night of May 16, Almasy led two He-111s southeast into the Libyan desert. Skimming the desert floor to underfly British radar, they crossed the Egyptian frontier to a prominent jebel (isolated peak) selected as a rendezvous point. Almasy scanned the serir (firm sand area) for the general’s landing marker. There was none. After circling the jebel, he and his escort flew on toward Cairo until their fuel gages dictated a return to base. Days later they learned that el Masri’s plane, piloted by two young Egyptian air force officers, had developed engine trouble and crash-landed only 10 miles from Cairo. Knowing there would be a dragnet for fifth columnists, the general and his coconspirators hid out in Cairo before being tracked down on June 6.

Undaunted, Ritter launched their second spectacular enterprise, infiltrating spies into Cairo, “a notorious hotbed of valuable gossip and rumor.” With British forces astride the coastal highway, agents would have to be taken all the way to the Nile Valley, well south of Cairo but near a town where they could catch a train to the capital. Ritter opted for aerial insertion, though the He-111’s 1,200-mile range was problematic. Almasy proposed driving overland using caravan tracks and explorers’ routes he knew, but he agreed to try aircraft first. He selected a landing site along the caravan track from the Farafrah oasis to Derut, an area he had surveyed in December 1933 for the Egyptian Aero Club’s first Oasis Circuit Air Race.

A lone jebel made a good landmark, and just south of it a strip of serir ran 60 miles to the Nile. For the spies to cover that distance, Almasy procured an Italian motorcycle, common in Egypt, which could fit into an He-111 and be abandoned near the railway station.

Crash-Landing in the Mediterranean

After a first insertion attempt was scrubbed, owing to the Abwehr’s inadequate preparation of the Cairo support network, Ritter flew to Hamburg and brought back two Arabic-speaking, Brandenburg-trained VertrauensmÄnner (confidential agents). June 17, just before takeoff, ground crew discovered a damaged tire on the lead He-111. Major Ritter, leading the mission, ordered the escort plane, unfortunately flown by a new pilot lacking desert experience, substituted as lead plane. Sensing trouble, Almasy and another pilot urged Ritter, who was not an aviator, to wait for the replacement tire or at least to switch pilots.

Ritter feared more delays and refused. Tension mounted. Finally, Almasy exercised his prerogative as an attached Hungarian officer and declined the mission. By the time the planes reached the landing site, the sun was low, so pebbles cast shadows looming like rocks. The nervous pilot refused to land. Exasperated, Ritter ordered a return to base, which they found under attack. Diverted to Benghazi, nearly out of fuel, one plane barely reached an emergency strip, but Ritter’s aircraft had to ditch in the Mediterranean. In the impact one of the V-männer was killed by a shifting crate, and Ritter broke his arm.

Operation Salaam

After nine hours clinging to a small raft, the battered survivors washed up on a beach and trudged to an Arab village before being picked up by Storks of the Desert Rescue Squadron. “I felt that to a great extent I had myself to blame for the failure,” Ritter admitted, “initially for not switching planes [pilots] and then for not having ordered Almasy to take my place. He might have been able to persuade the timid pilot to land.” Before leaving for a hospital and Abwehr headquarters in Berlin, Ritter told Almasy, “Count, you will have to take over now and proceed with our alternate plan to take the next pair of agents by car across the desert.” On June 27, Ritter radioed Almasy to report to Berlin Central to discuss “the penetration of Southern Egypt via the desert.”

Admiral Canaris approved their plan as Unternehmen Salam (Operation Salaam) in September, and they selected two more Arabic-speaking V-männer, former residents of Egypt and Palestine, for Unternehmen Kondor (Operation Condor), plus support personnel from the Brandenburg Regiment. When Almasy returned to Tripoli in December, Panzerarmee Afrika, forced out of Cyrenaica, was regrouping and reinforcing for its January 21 surprise attack. The offensive regained all territory previously lost, coming to a halt 100 miles east of Derna on February 7, 1942.

The Mission Must Succeed

Good intelligence was now never more urgent as Rommel was planning his May thrust toward the Nile Delta, which would be blocked in August at El Alamein. The Abwehr had been providing him with decrypts of highly informative cables to Washington from Colonel Bonner Fellers, U.S. military attach, at British headquarters in Cairo, but knew the source would eventually be discovered. Canaris decided that only an agent network could replace Rommel’s “little fellers” and gave Salaam the green light.

Almasy’s initial attempt was another fiasco. Striking southeast from Jalo on April 29 with five vehicles, he tried crossing Libya’s Calanscio Sand Sea by a passage shown on his Italian maps as serir but that was actually sand dunes. Then his sergeant and medical corpsman came down with desert colic, and he lost a vehicle to transmission failure. On May 7 he returned to Jalo, grumbling, “What were those guys [Italian cartographers] doing between 1931 and 1939, anyway?”

But the mission had to be accomplished. The only way was risky, continue south on the Palificata (an Italian track marked with poles one kilometer apart), around the Sand Sea, to the Kufra oases, then drive east to the Switzerland-sized Gilf Kebir massif, following his own route from 1932; the Gilf he could cross through an obscure wadi. The problem was that the British Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) of fellow Zerzura Club member Colonel Ralph Bagnold had seized Kufra from the Italians. Almasy would have to turn southeast off the Palificata north of Kufra and traverse unfamiliar terrain until he crossed his 1932 tracks.

“That Changes My Whole Plan”

Evacuating his ailing men to Tripoli on May 11, Almasy drove with the remaining seven Brandenburgers and five vehicles to the Campo 4 landing strip at kilometer 276 (from Jalo) to wait for additional fuel and supplies. The original plan was a round trip of 2,000 kilometers (1,200 miles); the new route, swinging much farther south, was 4,200 kilometers (2,600 miles). They would need twice as much of everything.

“At first it looked as if there wasn’t room in the vehicles for enough gasoline and supplies,” Almasy recorded in his journal, ”but somehow it had to be.” Finally he worked out a plan. “I’ll go with two Ford station-wagons (Inspector and President) and two Ford Commercials (Maria and Purzel). The latter two we’ll have to sacrifice. Purzel has to go 800 kilometers, Maria a further 500. I’ll have to get by with one vehicle the last 200 kilometers to the objective. Out and back, 4,200 kilometers—is that realistic?”

The trucks would be abandoned, hidden on the way out as “depots” of gasoline, water, and rations for the return trip. Almasy also had to reduce his team: one fewer truck meant less food and water. He sent his medical officer and a corporal back to Jalo in the superfluous truck, taking with him, besides the two V-männer, only three radiomen-drivers. All, including Almasy and the agents, would drive.

At 8:30 am on May 15, with two hours of sleep after a night spent recalculating and restowing the indispensable gasoline, water, and rations, Salaam again got under way, making 210 kilometers the first day. After digging Maria out of soft sand, they found and began following Italian multi-tire truck tracks dating from 1932-1935, still evident owing to lack of rain. The second day they came across fresh tracks: 104 large trucks headed for Kufra from the Gilf Kebir. The following day, after reaching Almasy’s 1932 tracks, they found two new Chevrolet 3-ton trucks bearing Sudan Defence Force (SDF) markings, apparently abandoned. Their odometers showed 435 miles—the distance from the Upper Nile River port and Cairo-Khartoum rail junction of Wadi Halfa. Almasy realized Kufra was being supplied by SDF convoys following prewar explorers’ tracks from Wadi Halfa, not by the Free French from Equatorial Africa as the Germans had thought.

Two days later, near the base of the Gilf Kebir: a windfall. Parked in the desert were six SDF 5-ton trucks. They carried empty fuel drums, apparently emptied by a Kufra convoy, but their tanks were full, and after draining them, Salaam had 500 extra liters of gasoline. “That changes my whole plan,” Almasy recorded. “I can make my objective with both station-wagons, and probably even get one of my trucks back home. Before leaving, he ordered sand put into the trucks’ oil sumps, a different amount in each one so their engines would not all seize up at the same time. “That way [the British would think] it might well have been an evil ghibli [sandstorm].”

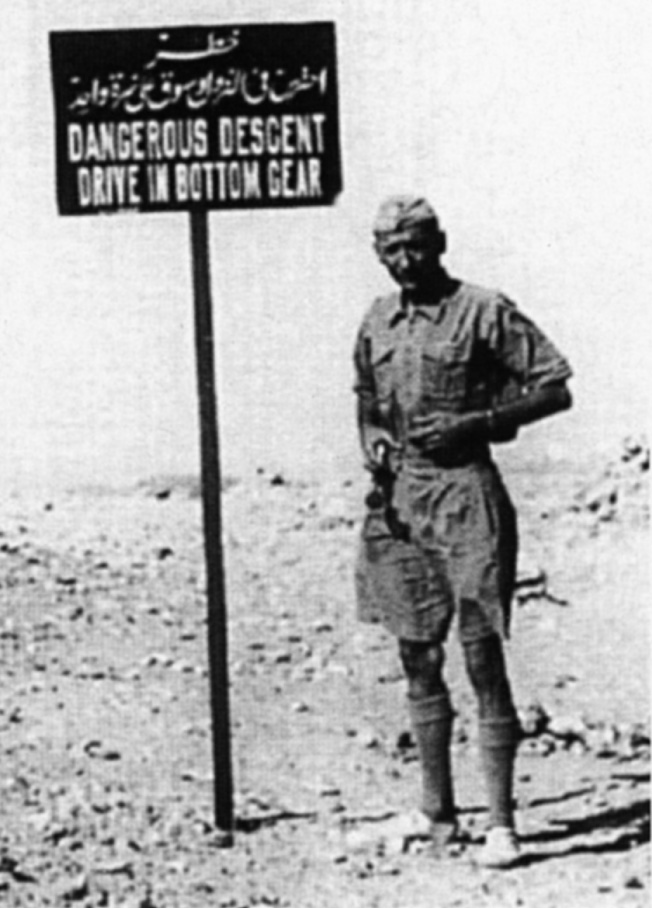

Early on May 23 the station-wagons crossed the Dakhla-Kharga road. It looked unused. Because off-road driving was consuming gasoline so fast, Almasy decided to take the road instead and bluff his way through Kharga. “After five kilometers,” he wrote, ”I stopped and again impressed on the men in the rear car that under no circumstances were they to lag behind, that they would stop only when I stopped, and move out when I did. The submachine-guns were set on ‘FIRE,’ but should only be used when I began firing.”

“Shooting Forbidden, at Most a Salute”

In the marketplace two khaffirs (watchmen), one armed with a pistol, blocked their way. Almasy stopped. “One greeted me respectfully in Arabic, pointed to his mouth and said, ’No Inglisi.’ I greeted him back and said I spoke Arabic. The man was delighted and told me the cars had to go to the markaz (government building), since anyone driving through had to file a report with the muhafiz (commanding officer). I replied that of course the bimbashi (major) would make a report, but that I was merely transporting the bimbashi’s baggage and had to go straight to the railway station.”

“Where is the bimbashi?”

“In the fourth car.”

Surprised, the man looked in the direction we had come. I asked him, “How many cars are behind me?”

“Only one.”

“Good.” I pointed at one of the khaffirs. “You stay here and wait for the other two cars. The bimbashi is riding in the fourth car. You will show him the way to the markaz.” Then I turned to the other one: “And you climb aboard and show me the fork to [the railway].”

“Hadr, Effendi.”

Thirty kilometers from Assiut, Almasy left the second station wagon, ordering the two Brandenburgers in it to wait for him only until 5 pm, then to return the way they had come. Nearing the Nile, he turned off onto an obscure camel track and at 2 pm arrived at the rim of the Egyptian Plateau. Below, “scarcely four kilometers away, lay the deep green valley with the glistening silver river, the great white city, countless esbahs [native huts] and country houses,” Almasy recorded.

Then the two V-männer changed into their civilian clothes and cover identities and walked the last two miles to the railway station. “Not much was said, a couple of handshakes, one last photo, a curt ‘farewell,’ and then I drive back with Munz on our own tracks,” Almasy recalled. ”We don’t lose much time by the waiting station-wagon … before us again lies the 2,200 kilometer stretch which we had just put behind us.”

The night of May 25, they camped by their first “depot,” up a narrow gorge in the Gilf Kebir. As the sun rose they were startled to see two parks of 28 and 30 trucks (guarded this time) out on the plain and another SDF convoy halted in front of their ravine while the Sudanese drivers and guards performed their Muslim prayer ritual. While anxiously waiting for the convoy to leave, Almasy had his men cannibalize the truck’s tires and water pump for the station wagons.

Finally back on the track, they noticed a huge dust cloud behind them, signifying a second enemy column. For several nerve-wracking hours Almasy figuratively drove with one eye on the convoy ahead and one on the rear-view mirror. The convoy ahead stopped for a rest, but the column behind continued to close in on them. Salaam would have to test its stealth. Almasy waved the second station wagon up and told the two men in it to shut all the windows and follow close behind him.

“‘Shooting forbidden, at most a salute.’” They both grinned widely and said, ‘Yes, sir [in English].’ I gave Woermann the Leica: ‘Take a picture as we pass by.’” Slowly they rolled past the seemingly endless line of stationary trucks, men sprawled in the shade underneath. “The sun was in the Sudanese soldiers’ eyes so the insignia on the station-wagons could scarcely be recognized,” Almasy recalled. “I waved, some Sudanese stood up and waved back.”

Late in the morning of May 29, Almasy and his three Brandenburgers, all in one station wagon, pulled into Jalo on their last gasoline. Almasy flew to Rommel’s headquarters, reporting the following day: “Herr Generaloberst, Operation Salaam successfully concluded. Operation Condor can now begin.” In conversation, the general mentioned narrowly evading capture in an LRDG raid just the day before and that the British commandos had captured two Abwehr radiomen Rommel’s staff had brought forward to his mobile headquarters owing to a shortage of communicators.

Almasy realized the radiomen were the Brandenburgers he had posted at main headquarters to link him with Abwehr Central, and they had codes and details about Salaam and Condor. It was an awkward moment, embarrassing to everyone, which Rommel dispelled by congratulating Almasy on his success, promoting him to major, and awarding him the Iron Cross, First Class. In the event, apart from Rommel’s security breach, Condor turned out to be a comedy of errors (though it provided the plot of Ken Follett’s 1980 novel, The Key to Rebecca, and other fictional works), ending in the July 25 arrest of the agents and their Egyptian accomplices, including future president Anwar Sadat.

Dora and Bunny-Hop

In June 1942, Almasy returned to Europe on recuperation leave, detouring through Italy to visit his Zerzura expedition colleague Pat Clayton, interned in a POW camp after his capture in an early LRDG raid on Kufra. Over drinks in a local trattoria during a few hours’ parole, Almasy told Clayton about Salaam—and apparently more, as Clayton’s censored letters home began to refer to his “daughter Dora.” As the Claytons had no daughters, his wife turned the letters over to MI-9, the escape and evasion section of British Intelligence and originators of a mail code used by selected officer POWs.

Dora, unknown to the British, was the codename of an Abwehr operation to prepare a chain of secret airstrips across the Sahara, intended to launch aircraft to shoot down Cairo- or India-bound air transports from the U.S. Atlantic seaboard crossing Equatorial Africa. The following month, a Leutnant von Leipzig led a hundred French-, English-, and Arabic-speaking Brandenburgers in 24 heavily armed, captured British vehicles to Lake Chad in French Equatorial Africa. Before MI-6 made sense of Clayton’s tip, nomads reported the strangers to the Free French at Fort Lamy, and with secrecy blown and taking casualties in skirmishes, von Leipzig retreated back into Libya.

Almasy would have learned about Operation Dora in April, when he and another Abwehr officer, Witilo von Griesheim (code-named Wido), briefed Admiral Canaris in the Tripoli Abwehrstelle on their respective operations. Von Leipzig was part of Sonderkommando Wido, based in the Fezzan in southern Libya. Did Almasy tell Clayton about Dora thoughtlessly or deliberately? Had Ritter’s bungling or the Abwehr’s seemingly intentional organizational incompetence (perhaps ascribable to Canaris’s anti-Nazi sentiment) disillusioned Almasy? Had he decided, after the German defeat at Stalingrad and impending defeat at El Alamein, to make his separate peace?

In the spring of 1943, Dora resurfaced tentatively as Unternehmen Etappenhase (Operation Bunny-Hop). Major Seubert’s plan was to place three clandestine weather stations at remote desert landing sites in North Africa, partly making up for the loss of North African bases caused by the Axis surrender in May. Besides useful data, the weather stations would also provide cover for intelligence communications for subversion and propaganda operations among dissident Arab and Berber groups as well as an opportunity to assess the feasibility of interdicting air routes moved to North Africa with the Allied victory. In September Seubert brought in Vesuchsverband (Research Unit) 2, a Luftwaffe special operations squadron established to support the Abwehr. By November, its commander, Major Karl Gartenfeld, had set up an outstation for Bunny-Hop at the Athens-Kalamaki airfield, used by the Abwehr since the loss of its Tripoli base.

At this point Almasy’s documentary trail fades, but the Abwehr’s desert aviation expert’s fingerprints are all over Bunny-Hop. The first weather station site selected, probably by Almasy, was the abandoned Italian airstrip at El Mukharam, 60 miles inland from Sirte on the Libyan coast. Before large transport aircraft could bring in fuel, supplies, and personnel, however, a pathfinder team would have to fly in to prepare the landing site. The Storks could land on unprepared strips, but their range was only 236 miles. Almasy, a Royal Egyptian Aero Club founder, would undoubtedly have recalled that the 1937-1938 Hoggar Air Races in North Africa were won by a Messerschmitt Bf-108 Taifun (Typhoon) and that the desert-proven Me-109 predecessor could fly 620 miles before refueling. El Mukharam, however, was at least that far from Athens, and Taifuns would be useless coming in with dry fuel tanks.

End of the Abwehr, Rise of the Sicherheitsdienst

In the early morning of November 12, 1943, a single He-111, the Luftwaffe workhorse, took off from Athens-Kalamaki towing an Me-108 with pilot, navigator-radioman, and two soldiers aboard. Over the Libyan coast, the duo descended to 3,300 feet; the Taifun’s pilot started his engine and slipped the tow, then flew with the sunrise to El Mukharam. At 8:25 am, the tow plane landed in Athens, and Tosca informed Berlin, according to a British decrypt, “First operational flight carried out stage by stage without incident; Me-108 arrived safely …”

Who had conceived aero-towing the Taifun like a glider to conserve its fuel? Almasy’s association with gliders went back to age 14, when he built and crashed in one. In the 1920s, he organized glider training for the Hungarian Boy Scouts and cofounded the Air Scouts in 1933. He organized a glider school in Cairo in 1935, importing Hungarian gliders and flying one around the Pyramids at Giza. In 1949 he would tow a glider from Paris to Cairo, with stops at Rome and Tripoli. Was he, as British historian Saul Kelly suggests, trying out the technique he devised for Bunny-Hop?

The first supply flight to El Mukharam was to be flown by two He-111s in two or three days, but engine trouble and a November 16 air attack on Kalamaki forced postponement. Weeks of radio silence followed, during which the officer in charge at El Mukharam, a lieutenant named Duemke, was recalled to Berlin. Then, on February 12, 1944, Duemke unexpectedly radioed Athens, ”Stop radio traffic Tosca-Traviata [Athens-El Mukharam]. Rescue only in emergencies.”

What had happened was that the Abwehr’s longtime Nazi rival, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD, Security Service) had finally triumphed. The SD had had Admiral Canaris on its radar in investigating the Schwarze Kapelle (Black Orchestra), a high-level, anti-Hitler conspiracy (Canaris had, in fact, anonymously fed MI-6 information as early as 1941). Then, at an early February meeting with Hitler present, Canaris heedlessly expressed the opinion that Germany could not win the war.

On February 18, 1944, Hitler abolished the Abwehr by decree, ordering the SD to assume its functions, and transferred Canaris to a meaningless post (he would be arrested after July’s assassination attempt against Hitler and executed a month before the war’s end). Two days later the Luftwaffe formed a new special operations organization reporting to the SD. Named Kampfgeschwader 200 and commanded by bomber pilot Lt. Col. Werner Baumbach, KG 200 incorporated the two Vesuchsverbände. Vesuchsverbänd 2 became KG 200’s I Gruppe, and Major Gartenfeld was replaced by a “politically reliable” Major Adolf Koch.

Almasy After the War

Almasy missed the aero-tow trial, having been posted to Istanbul the previous November 7 on liaison with pro-German Egyptian exiles. When he returned to Berlin, he must have been sent to Athens by Seubert to take charge of Bunny-Hop no later than February 12 because on February 13 a curious communication from Tosca (Athens) advised Berlin that the Kommando at Traviata had “learned from caravans in transit that [the oases] Hon, Bungen and Socna are only manned by a few Arab policemen. Sirte only lightly guarded. Sending of agents to work in Benghazi very possible.” The message was atypically signed “Teddy.” Zerzura Club members would recognize Teddy as the lifelong nickname of Laszlo Almasy.

This use of actual place names with the codename Traviata revealed Bunny-Hop’s area of operation to the eavesdropping British. An immediate search of the Sirte Desert within 20 miles of the coast turned up nothing, but over the next couple of weeks bedouin reported having seen unidentified “Britons” and airplanes deeper in the desert since November. Then, on March 14, an SDF armored-car platoon reached El Mukharam and found a Savoia-Marchetti SM 82 Cangaru trimotor transport on the airstrip. After a firefight, in which the plane went up in flames, the SDF captured four of Duemke’s men from I Gruppe KG 200, and found 2,000 gallons of aviation gasoline.

After the patrol left with the captives, an Arab watching saw two more three-engined aircraft and an Me-108 land. The aircrews then torched the Taifun, loaded the gasoline onto the trimotors, and took off toward Tunisia and Morocco, which were, according to the prisoners, the locations of two more weather stations. The prisoners also revealed that a Dornier 200 (a captured Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress used by KG 200 as a transport) had also flown supply missions.

On May 15 an SDF patrol observed a B-17 in Luftwaffe insignia land and opened fire on it. The plane “managed to take off with a port and starboard engine running.” Three days later, Tosca radioed Berlin, “We cannot keep to date of operation planned as plane and crew have been shot up and are out of action.” RAF photo-intelligence confirmed that the B-17 had indeed made it back to Athens and had been repaired. Amazingly, the Cairo MI-6 station continued to receive reports of German aircraft landing at El Mukharam and two other abandoned Italian airstrips as late as June 1944, a full 13 months after the end of the Desert War.

It is not known when MI-6 realized that Almasy was tipping them to Abwehr operations in North Africa or whether he reported from Istanbul; nor do we know whether he provided information from Budapest, after his return in the autumn of 1944, on German efforts to exterminate Hungarian Jews and Soviet actions to establish a Communist government in Hungary. What is known is that MI-6 rescued or collaborated in the rescue of Almasy from a Hungarian communist prison.

In November 1946, after eight months of interrogation during which his weight dropped from 154 to 90 pounds, his “class enemy” and Nazi-sympathizer conviction was quashed for lack of evidence. In January 1947 the NKVD (Soviet secret police, later KGB) arrested him on suspicion of “links with Western Intelligence.”

Almasy managed to contact Egyptian King Farouk’s cousin, who contacted MI-6, then delivered a generous bribe to Almasy’s Hungarian jailers to permit him to escape. MI-6 agents hid him in Budapest, then in June 1947 smuggled him into the British zone of Vienna with false travel documents under the name Josef Grossmann. The British consulate in Trieste put him on a train to Rome with a British passport, pocket money, and an airline ticket to Cairo. Almasy and his MI-6 rescuers gave an NKVD hit team, following his trail to Trieste and Rome, the slip by minutes.

In Cairo, Almasy regained most of his health and resumed his prewar life, teaching wealthy young Egyptians to fly and leading desert tours for rich Americans. In May 1950 he achieved a long-held ambition when King Farouk appointed him director of the Fuad I Desert Institute. The appointment was formally announced December 30 at a glittering, Arabian Nights-style banquet for an international desert science conference, where Almasy, Ralph Bagnold, and Pat Clayton swapped war stories.

A few days later, Almasy collapsed from hepatitis brought on by amoebic dysentery, and he died on March 22, 1951, in the Salzburg clinic where he was being treated. His brother, Janos, found his Cairo apartment empty, his papers, diaries, expedition journals, and maps all inexplicably gone, and with them any evidence that might have filled the gaps in the Almasy story. Despite all the posthumous celebrity from The English Patient, Laszlo Almasy remains the quintessential mystery man of World War II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments