By Mason B. Webb

“I do believe that the United States fleet would not have been in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, had I been the chief of naval operations at that time.”

So stated Admiral James O. Richardson after the stunning Japanese attack that nearly destroyed America’s Pacific Fleet on that fateful Sunday and propelled the United States into World War II.

So stated Admiral James O. Richardson after the stunning Japanese attack that nearly destroyed America’s Pacific Fleet on that fateful Sunday and propelled the United States into World War II.

In Pearl Harbor Countdown: Admiral James O. Richardson (Pelican, Gretna, LA, 2008, 543 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, softcover, $25.00), a big and compelling biography of a now almost forgotten historical figure, author Skipper Steely offers an illuminating portrait of a naval officer who could have changed history, if only America’s leaders had listened to him.

Richardson, who commanded the Pacific Fleet until January 1941, had played a central role in developing and implementing War Plan Orange, the military strategies, plans, and exercises launched in 1924 to check Japan’s expansionist moves in the Pacific. From his intense involvement in these exercises, it became clear to Richardson that the fleet should not remain at Pearl Harbor. In his estimation, the fleet was not prepared, the country was open to attack, and the facilities at Pearl Harbor were inadequate for training the sailors whose duty it was to defend the Pacific and America’s West Coast.

Richardson’s own training, expertise, and experience led him to the unshakable conclusion that a Japanese attack against Pearl Harbor was inevitable. The admiral risked––and ultimately sacrificed––his long and distinguished Navy career by locking horns with Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, Chief of Naval Operations Harold Stark, and even President Franklin D. Roosevelt, trying in vain to convince them of Japan’s intentions and the Navy’s vulnerability.

But Knox, Stark, and Roosevelt finally had heard enough and refused to listen. When Richardson continued to repeatedly criticize the executive decision to maintain the fleet in Hawaii, he was relieved of his command. After the attack, it became painfully obvious that Richardson had been right all along.

Pearl Harbor Countdown is a big, important book about one of America’s greatest military disasters––a disaster that might have been averted had his superiors heeded Admiral Richardson’s warnings. Highly recommended.

Deceiving Hitler: Double Cross and Deception in World War II, by Terry Crowdy, Osprey, Oxford, UK, 2008, 352 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.95.

Deceiving Hitler: Double Cross and Deception in World War II, by Terry Crowdy, Osprey, Oxford, UK, 2008, 352 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.95.

One of the most fascinating aspects of World War II is the cunning and trickery employed by the Allies to fool Hitler and his commanders into thinking they were about to do one thing when, in fact, they were about to do something altogether different.

Perhaps the best-known example of wartime deception was Operation Fortitude, the Allies’ successful attempt at using a fake army, fake radio traffic, and fake landing craft in conjunction with a very real George S. Patton, to convince the Nazis that the main invasion of the Continent would take place at the Pas de Calais. So convinced were the Germans that, even days after the invasion of Normandy had been launched, Hitler was reluctant to move any units from Calais to Normandy.

But, as Crowdy points out, Operation Fortitude was only one in a long series of deceptions designed to arouse enemy suspicions and force them to act in a desired fashion. Whether it was dressing up a corpse in a British uniform and outfitting him with a briefcase that contained false plans for an invasion of Sardinia and Greece instead of the real target, Sicily, and setting him adrift off the coast of Spain; or using look-alike “doubles” of famous personalities such as Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery; or employing dummy tanks, aircraft, and landing barges that, from the air, looked like the real thing, the Allies’ disinformation campaign worked beyond the planners’ wildest dreams.

In Deceiving Hitler, Crowdy also details the careers of numerous spies, agents, and double agents whose work did much to confuse and confound the enemy, all the while risking exposure and their lives. We meet the operatives with such code names as Garbo, Dragonfly, Tate, Rainbow, Father, Careless, and Mutt and Jeff, and learn exactly how they contributed to German confusion and Allied victory.

Throughout Crowdy’s constantly entertaining book the reader will encounter colorful characters, preposterous-yet-true schemes, and fabulous plans and plots that fooled the enemy and helped ensure an Allied victory. A must-read book of the can’t-put-it-down variety.

Pius XII, The Holocaust, and the Cold War, by Michael Phayer, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2008, 332 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $29.95.

Pius XII, The Holocaust, and the Cold War, by Michael Phayer, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2008, 332 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $29.95.

For the past 60-plus years, much controversy has swirled around what Pope Pius XII and the Roman Catholic Church did or did not do regarding the mass murder of millions of Jews by the Nazis.

Delving into this complex issue is Michael Phayer, an emeritus professor of history at Marquette University and Holocaust scholar who has specialized in looking at the relationship between the Church and the Jewish Holocaust. In this new book, Phayer makes use of previously unavailable material to shed new light on the actions of the Vatican and of the man whom some have called “Hitler’s Pope” while others continue to campaign for his sainthood.

After Hitler gained power in Germany and another world war loomed on the horizon, the Vatican believed that it had to make a choice between opposing either Communism or Hitler’s Fascism. Convinced that Communist ideology would outlive Fascism, both Pius XI and his successor, Pius XII, reluctantly chose the Nazis as the lesser evil.

Although Pius XII denounced genocide in 1942, the crucial test for the pope came in October 1943, when the Jews of Rome were rounded up and hauled off to concentration camps. Pius XII was deeply troubled by the persecution of the Jews, but he feared that Catholics would be equally persecuted if he were to staunchly oppose Hitler. When 1,000 Roman Jews were shipped to their deaths at Auschwitz, the Vatican did not protest, a silence that has been interpreted as either complicity or cowardice ever since.

Phayer also delves into new documents that shed light on the Vatican allowing Holocaust perpetrators to escape justice by fleeing to South America after the war.

Phayer’s work is a detailed look at a complex man caught on the horns of one of history’s greatest dilemmas.

Intrepid: The Epic Story of America’s Most Legendary Warship, by Bill White and Robert Gandt, foreword by John McCain, Broadway Books, New York, 2008, 348 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $32.00.

Intrepid: The Epic Story of America’s Most Legendary Warship, by Bill White and Robert Gandt, foreword by John McCain, Broadway Books, New York, 2008, 348 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $32.00.

Sitting somewhat incongruously at Pier 86, located at West 46th Street and 12th Avenue on Manhattan’s west side, not far from the site of where the twin towers of the World Trade Center once stood, is a floating museum, the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid.

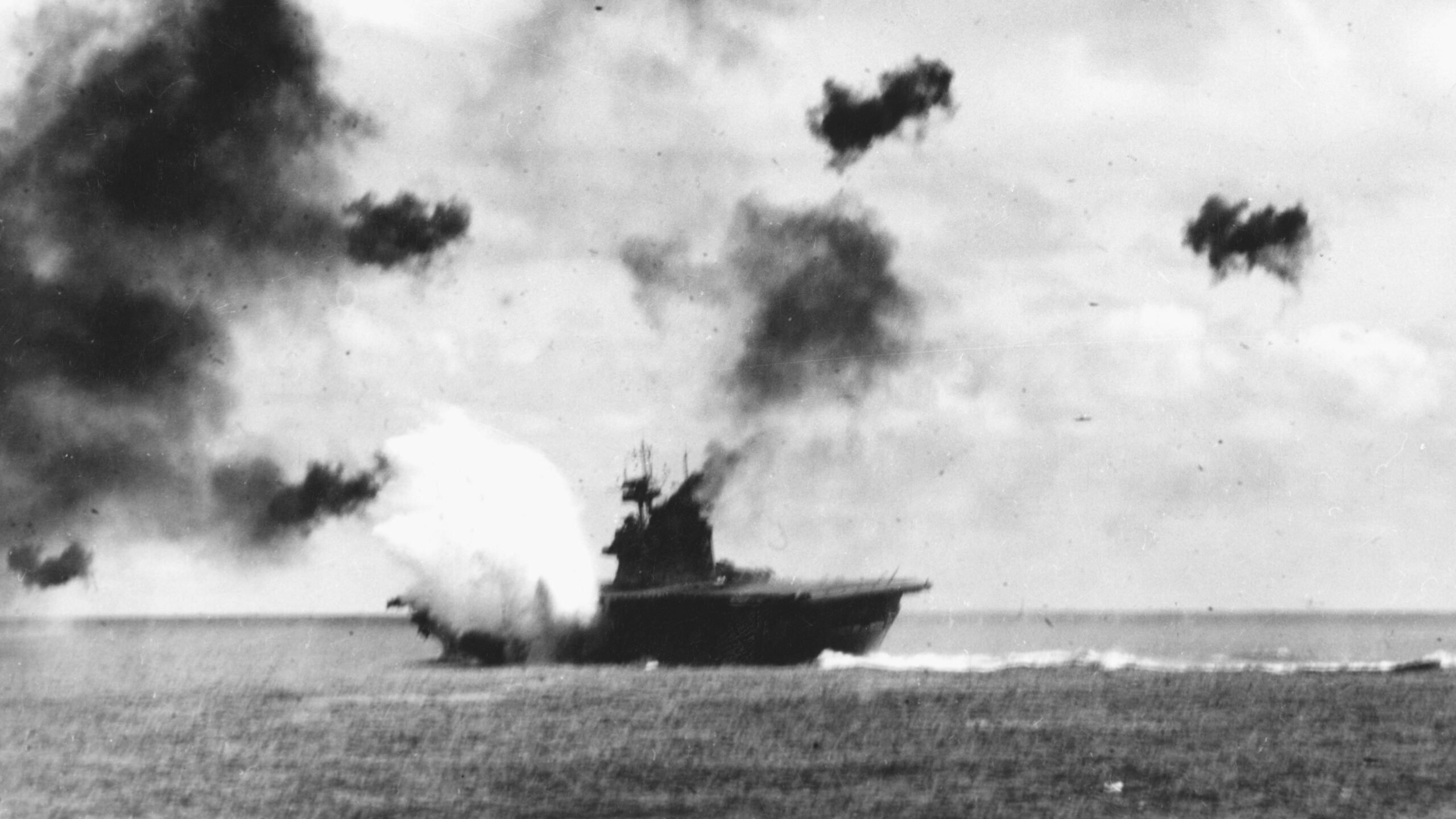

Since her launching in 1943, the 27,000-ton, Essex-class carrier has compiled a record unmatched by any other Navy vessel. During World War II, she took part in some of the most savage battles in the Pacific: Kwajalein, Truk, Peleliu, Formosa, the Philippines, and Okinawa. Surviving kamikaze and torpedo attacks, Intrepid and her crew of sailors and aviators covered themselves with glory.

After the war, unlike so many other ships, Intrepid was not scrapped. She was modernized and refitted and continued to serve her country as a Cold War attack carrier, a symbol of America’s steadfast resolve to defend freedom around the globe. During the Vietnam War, she was deployed to Southeast Asia, where she served as a platform for launching strikes against Communist targets.

She also served in peacetime, recovering returning astronauts who splashed down in the sea. Intrepid was also one of the main ships taking part in the nation’s bicentennial celebration in 1976.

But, like too many other vessels that had served proudly, Intrepid was slated for an ignominious end. Pulled by a tugboat from Quonset Point Naval Air Station in Rhode Island to the Philadelphia Navy Shipyard in March 1974, she was scheduled to be decommissioned and then cut to pieces, welders’ torches doing what Japan’s bravest warriors could not.

But then someone got an idea: perhaps the old ship could be saved and turned into a floating museum. It seemed far-fetched at the time ––how could the millions of dollars necessary to make the conversion be raised? Could enough civilian volunteers needed to perform all the work be found? And where could such a huge vessel be displayed?

The problems seemed enormous, the solutions impossible.

Enter Zachary Fisher, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants and a hugely successful New York developer and businessman. It was he who surmounted all of the hurdles and turned a dream into reality.

This outstanding book, by White, president of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum, and Gandt, a former U.S. Navy fighter/attack pilot, tells how Intrepid was saved from destruction and resurrected as one of the nation’s premier military museums. Both the book and the museum are tributes to America’s heritage and the courage of her fighting men.

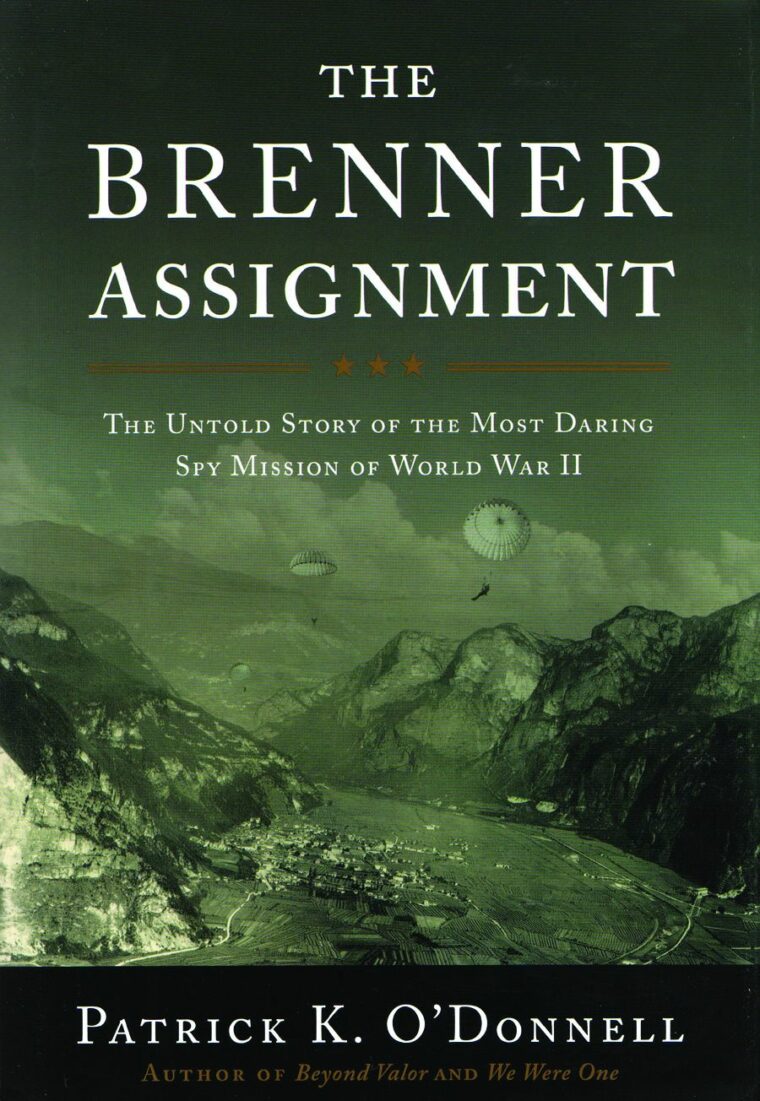

The Brenner Assignment: The Untold Story of the Most Daring Spy Mission of World War II, by Patrick K. O’Donnell, DaCapo, Cambridge, MA, 2008, 286 pp., photographs, maps, index, hardcover, $25.00.

The Brenner Assignment: The Untold Story of the Most Daring Spy Mission of World War II, by Patrick K. O’Donnell, DaCapo, Cambridge, MA, 2008, 286 pp., photographs, maps, index, hardcover, $25.00.

Since Roman times, the Brenner Pass has been an essential trade and military route through the Alps. During the war, it became a major supply artery for the Third Reich, as well as a symbol of the Hitler-Mussolini “Pact of Steel,” enabling German troops to be shuttled to the southern battlefronts and food from Italy’s rich agricultural regions to reach hard-pressed Germany.

This fragile link, tunnels beneath the mountain peaks, became the focus of an incredible plan: a secret American mission to infiltrate Nazi territory and cut the vital artery between Austria and Italy in order to hamper Germany’s ability to halt the Allied drive up the Italian peninsula.

It sounds like the stuff of Hollywood, but it’s all true, a behind-enemy-lines diary preserved in a buried glass bottle telling of the secret plans, along with a sensational cast of characters, the dashing team leader; the idealistic mastermind behind the operation; the beautiful and seductive Italian countess who is also a double agent; the cunning SS officer in determined, deadly pursuit of the spies and their partisan collaborators.

Drawing on a treasure trove of recently declassified files, private documents, and personal interviews, author O’Donnell reveals, for the first time, the facts behind the most daring covert operation of World War II.

Packed with action, suspense, intrigue, and even romance, this exciting tale of sabotage and survival behind enemy lines is one of the great untold adventure stories of the war. Highly recommended.

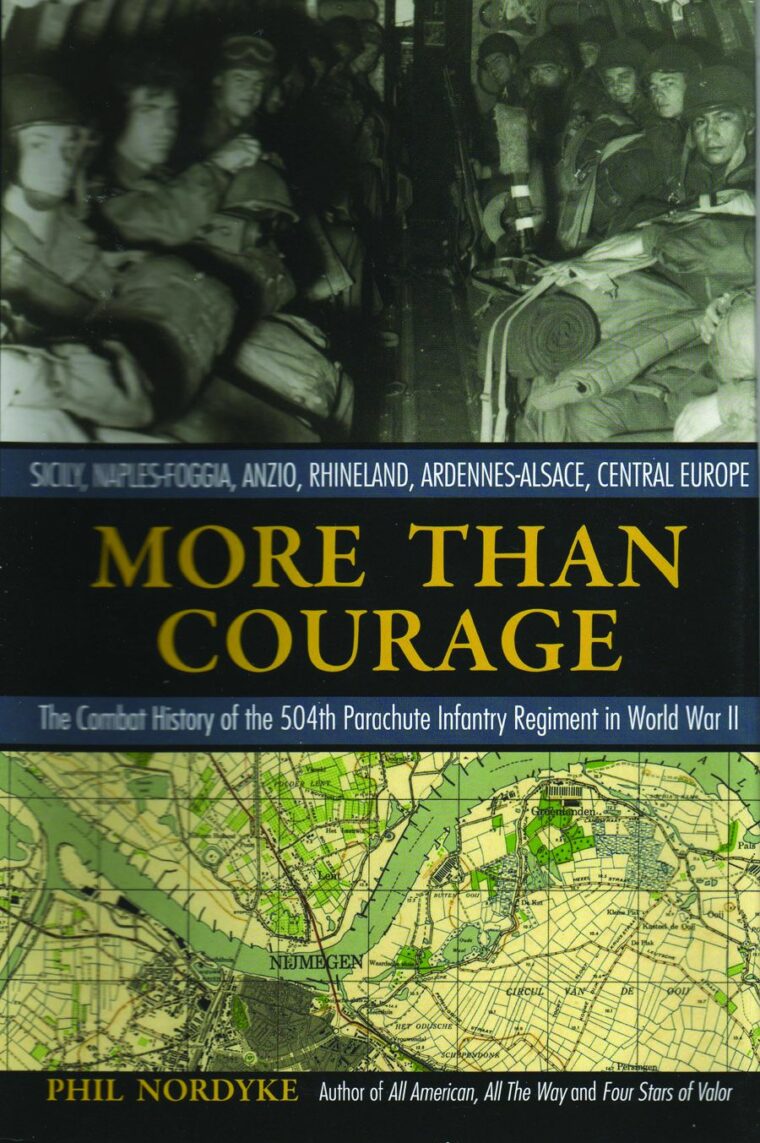

More Than Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II, by Phil Nordyke, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2008, 472 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $28.00.

More Than Courage: The Combat History of the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II, by Phil Nordyke, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2008, 472 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $28.00.

Few historians have captured the spirit and élan of the airborne forces the way Phil Nordyke has. The author of Four Stars of Valor, All American, All the Way, and The All Americans in World War II, has done it again, this time focusing on the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

Although the 504th did not take part in Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Normandy, the unit did practically everything else: executing combat jumps into Sicily, Salerno, and Holland; making an amphibious assault landing at Anzio; fighting in the rugged mountains of Italy; enduring brutal winter combat in the Belgian Ardennes; and making crossings under fire of the Waal and Rhine Rivers.

The 504th combat record is spectacular. No other American parachute regiment fought as many days (281) or under as many differing circumstances during World War II.

As the author notes in the introduction, “The paratroopers of the 504th were some of the toughest, best, most aggressive soldiers that America or any country has ever fielded. Despite fighting against some of the best troops of the German Army, the regiment never lost.”

Drawing on personal interviews, oral histories, and unpublished written accounts from more than 300 veterans of the “black-hearted devils,” Nordyke’s More Than Courage brings the history of the 504th to life, conveying with power what it was like to be there.

A fine book for anyone who likes his or her military history raw, rough, and unadorned.

Short Bursts

Defeat and Triumph: The Story of a Controversial Allied Invasion and French Rebirth, by Stephen Sussna, Xlibris, Philadelphia, 2008, 720 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $25.00.

Defeat and Triumph: The Story of a Controversial Allied Invasion and French Rebirth, by Stephen Sussna, Xlibris, Philadelphia, 2008, 720 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, softcover, $25.00.

This magazine does not often review self-published books. Too often they are poorly written and self-serving. But we have made an exception for this exceptional book.

Stephen Sussna, an emeritus professor of law, was the helmsman on LST 1012 during Operation Dragoon, the invasion of the French Riviera, on August 15, 1944. In Defeat and Triumph, he goes into great detail about all aspects of this important, dramatic, and controversial invasion and his ship’s role in the most dangerous and tragic event of the landings.

In his panoramic, well-researched history, Sussna thoroughly analyzes the pros and cons of Dragoon and provides a behind-the-scenes look at this large-scale but largely overlooked operation that ensured the liberation of France and the defeat of Nazi Germany.

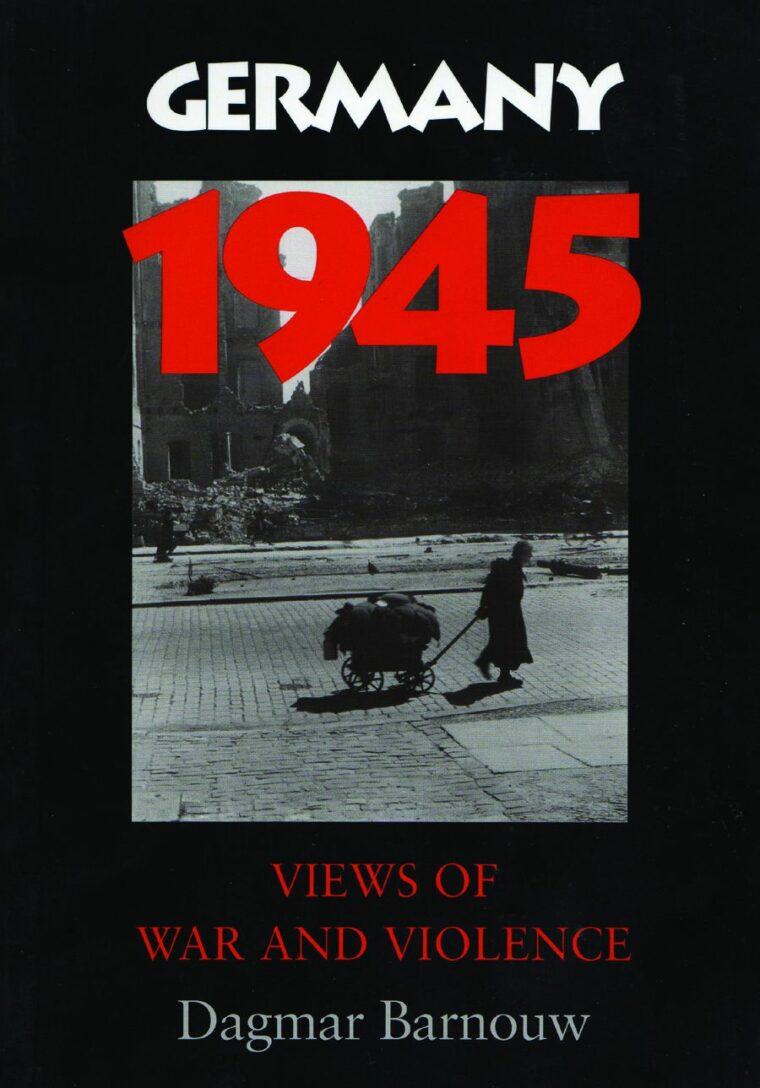

Germany 1945: Views of War and Violence, by Dagmar Barnouw, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2008, 255 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, softcover, $24.95.

Germany 1945: Views of War and Violence, by Dagmar Barnouw, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2008, 255 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, softcover, $24.95.

We are familiar with the images: destroyed German cities, long lines of pitiful refugees, demoralized German soldiers guarded by heavily armed GIs, stacks of dead concentration camp inmates. But what is the meaning behind the photographs? What do they tell us about war and the human condition, about the victors and the vanquished?

The brilliant, late University of Southern California professor Dagmar Barnouw, who wrote intellectually provocative works about the aftermath of World War II, is at her best in Germany 1945 as she uses photographs in an attempt to answer these and other unsettling questions.

As one reviewer noted, “Barnouw’s close readings try to suggest subtexts in the photographs that go beyond, and may even belie, the captions and texts that originally accompanied them. Barnouw aims at questioning a melodramatic victor’s gaze in order to arrive at a more fully compassionate point of view and to force the reader to confront and meditate upon images of death and destruction, of corpses and ruins, of hunger, suffering, hopelessness, and the aftermath of genocide.”

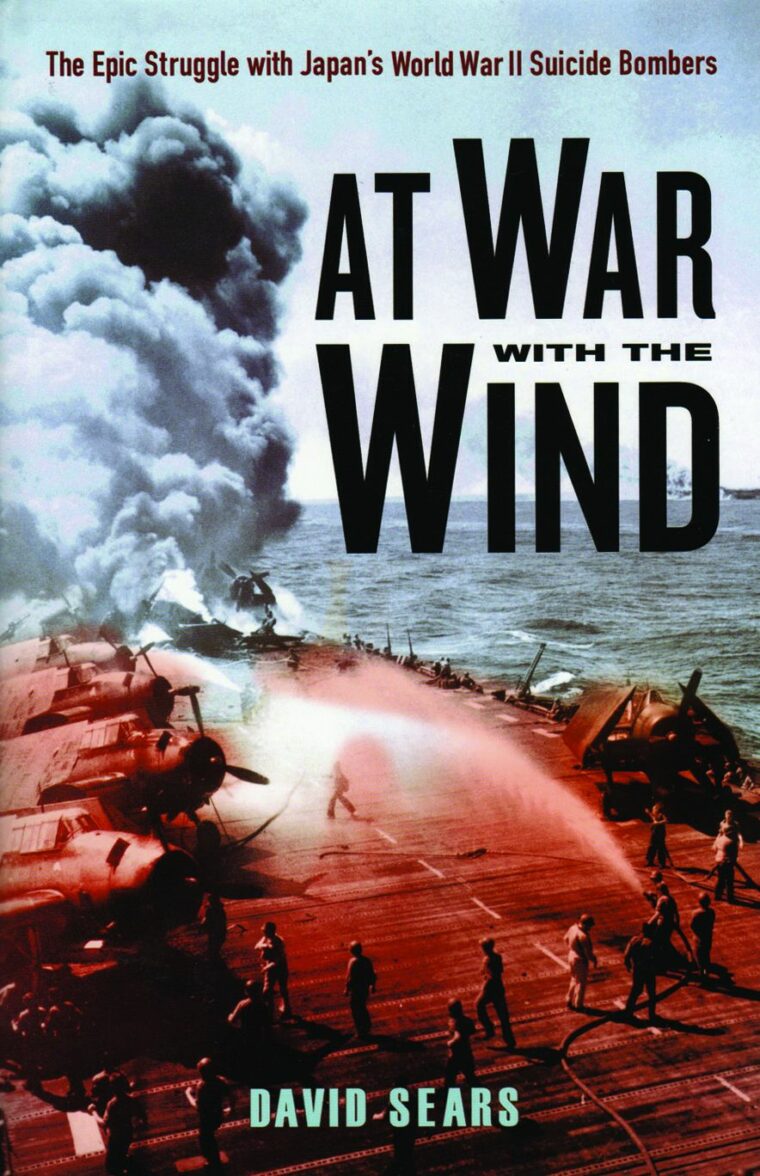

At War with the Wind: The Epic Struggle with Japan’s World War II Suicide Bombers, by David Sears, Citadel Press, Kensington Publishing, New York, 2008, 502 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $24.95.

At War with the Wind: The Epic Struggle with Japan’s World War II Suicide Bombers, by David Sears, Citadel Press, Kensington Publishing, New York, 2008, 502 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $24.95.

Anyone who ever thought that sea duty aboard a ship in wartime was safer than being in a foxhole or in an airplane needs to read Sears’s book.

In the closing months of World War II, a new and baffling weapon terrorized the U.S. Navy in the Pacific, enemy pilots who were determined to die in their attempt to sink American ships and forestall an invasion of their homeland. Known as kamikaze, or “divine wind,” these Japanese aviators were trained for one-way missions of mass destruction. Told from the perspective of the men who endured this horrifying tactic, At War with the Wind describes in nail-biting detail what it was like to be subjected to these devastating attacks from the sky.

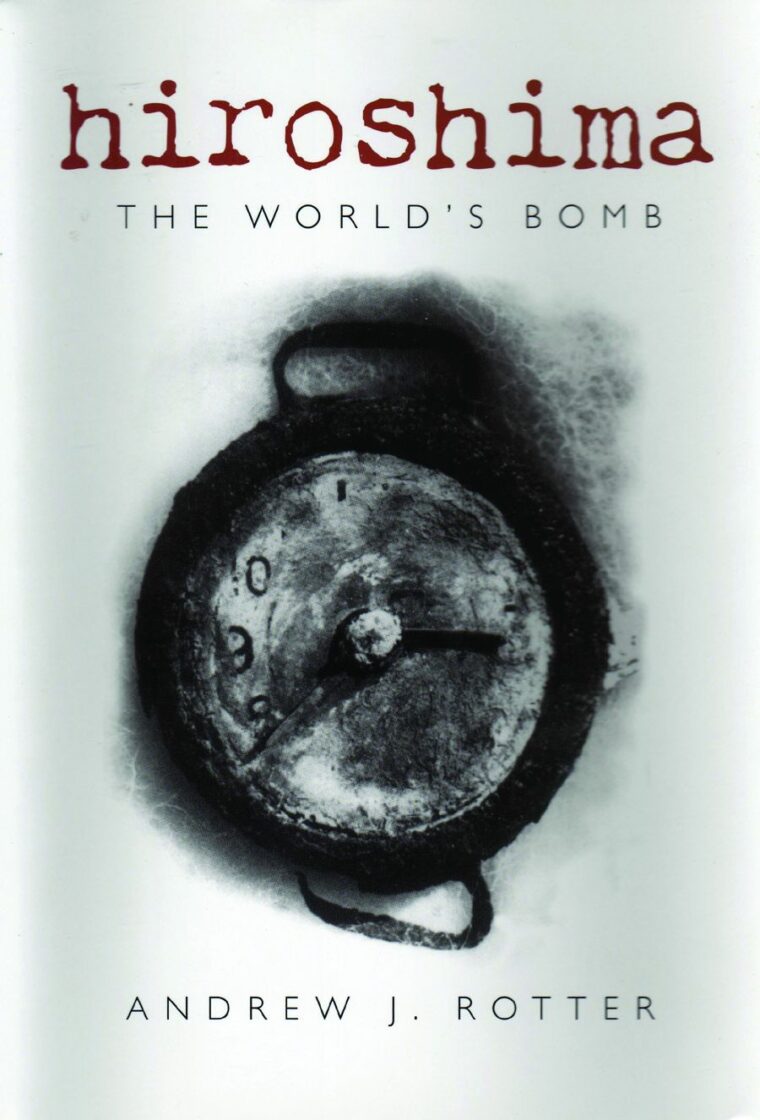

Hiroshima: The World’s Bomb, by Andrew J. Rotter, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2008, 371 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $29.95.

Hiroshima: The World’s Bomb, by Andrew J. Rotter, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2008, 371 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $29.95.

Many books have been written about the development and deployment of the atomic bomb, but Andrew Rotter’s book looks at the weapon in a new way––how it was the product of an international community of scientists, not just Americans. Other nations, including Germany and Japan, were working hard, albeit haphazardly, in the early 1940s to develop the bomb.

As Rotter points out, it is difficult to imagine any combatant nation refraining from using the weapon during the war if it had been able to build or obtain one. The international team of scientists organized by the Americans just happened to get there first.

Rotter shows just how far along these other nations were on the road to developing atomic weaponry and concludes with a sobering assessment of the danger faced by mankind since the proliferation of such devices.

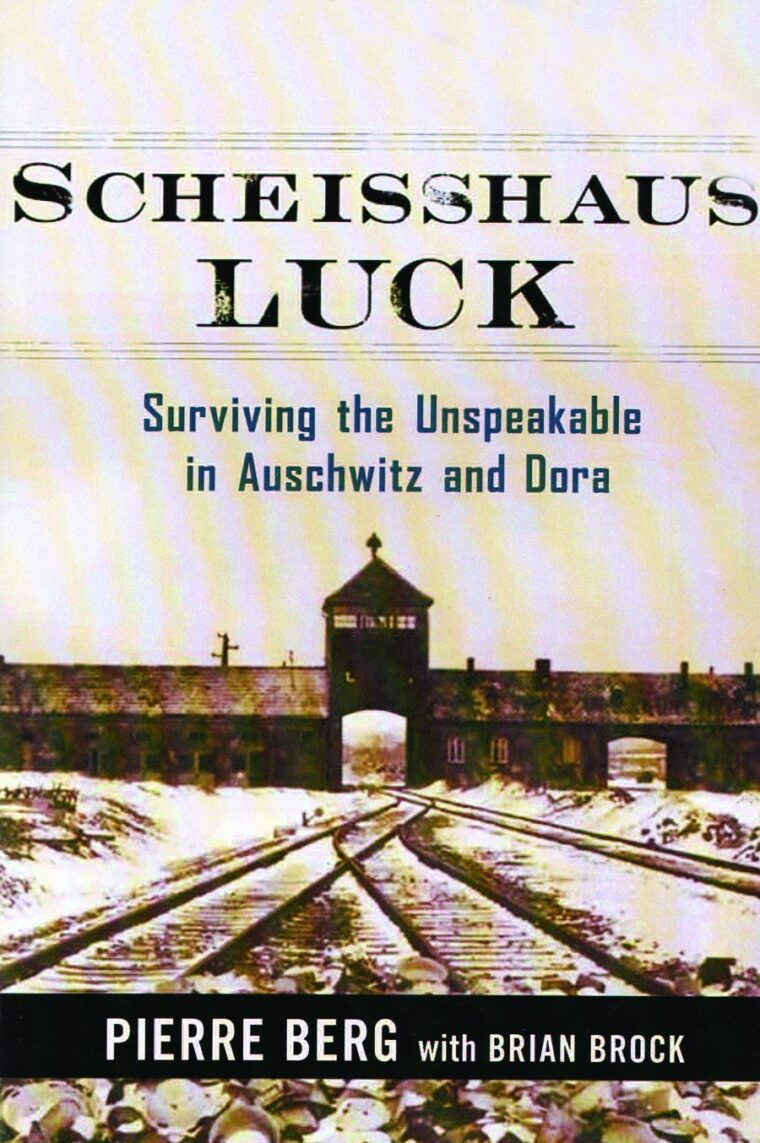

Scheisshaus Luck: Surviving the Unspeakable in Auschwitz and Dora, by Pierre Berg (with Brian Brock), Amacom Books, New York, 2008, 320 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $24.95.

Scheisshaus Luck: Surviving the Unspeakable in Auschwitz and Dora, by Pierre Berg (with Brian Brock), Amacom Books, New York, 2008, 320 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $24.95.

Berg’s book is a remarkable, unique personal account of the Holocaust from a non-Jewish French teenager’s point of view. From his arrest in 1943 to his incarceration in the death camp at Auschwitz and his eventual escape from the underground V2 rocket assembly plant at Mittelbau-Dora, Berg keeps the reader on the edge of his or her seat with his unsparing descriptions––frank, irreverent, and ironic, and with a hint of dry, gallows humor.

Now the Hell Will Start: One Soldier’s Flight from the Greatest Manhunt of World War II, by Brendan I. Koerner, Penguin Press, New York, 2008, 386 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $26.95.

Part history, part thriller, Now the Hell Will Start is the astonishing, unknown tale of Herman Perry, an African-American soldier who sparked the greatest manhunt of World War II and became the war’s unlikeliest folk hero.

Assigned to a segregated labor battalion, Perry was one of thousands of black soldiers ordered to perform the backbreaking chore of building the Ledo Road from the mountains of northeast India through the fetid, tiger-infested jungles of Burma and into China.

Unable to bear any longer the harsh conditions or his white superiors’ racist treatment, Perry deserted into the inhospitable wilds of the Indo-Burmese jungle where he learned how to survive. Befriended by a tribe of headhunters, Perry hid out while squads of U.S. military police sought to bring him back under American control and to a court-martial. A gripping, overlooked chapter of American history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments