By Lt. Col. Harold E. Raugh, Jr., Ph.D., U.S. Army (Ret.)

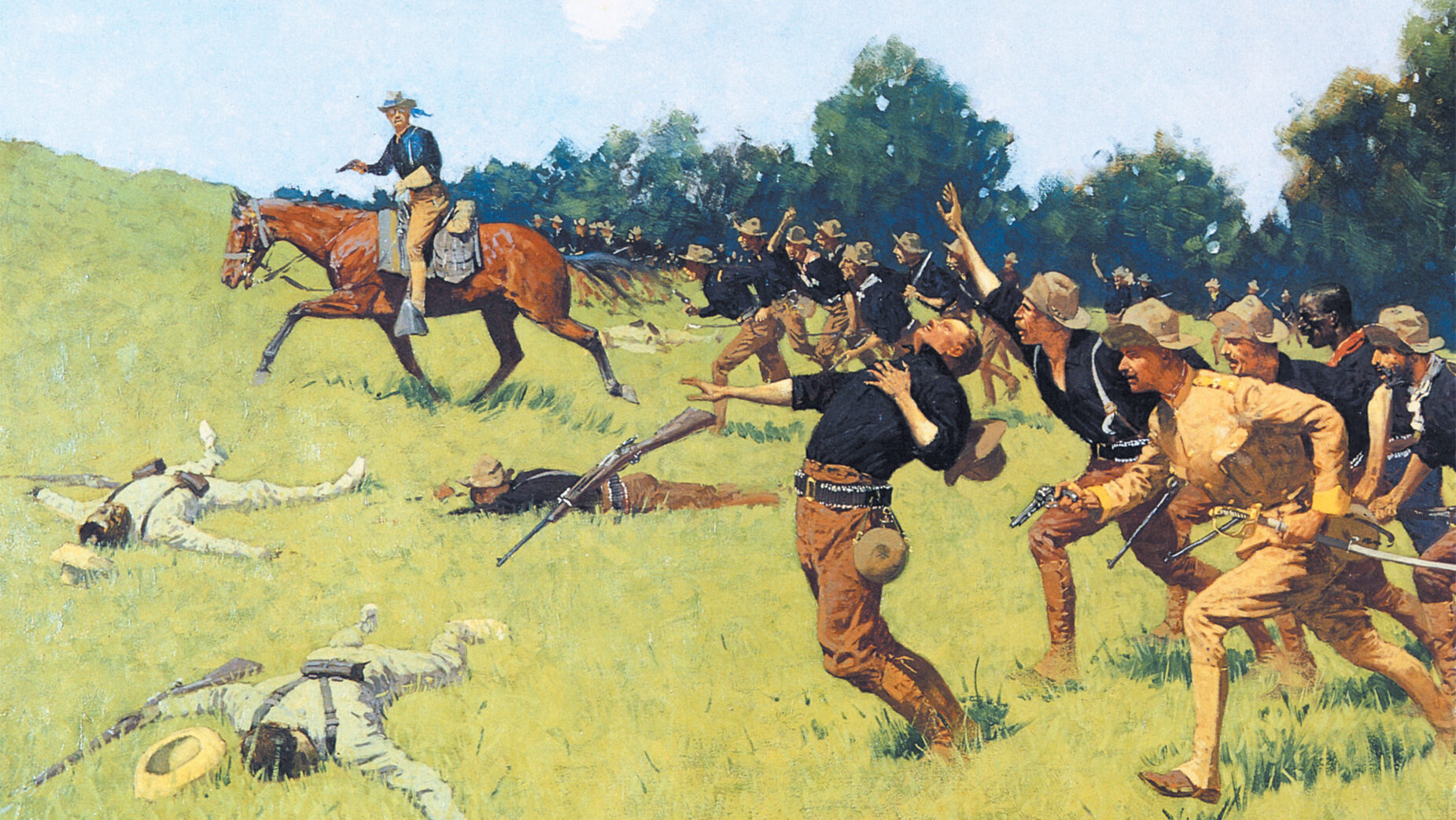

In 1898, with Indian campaigns in the past, the 28,000-man U.S. Army was a small frontier constabulary force scattered about the nation in 78 posts. Forty-three years later, after having fought in the Spanish-American War, in the Philippines, and on the Western Front during World War I, the U.S. Army in 1941 was, according to eminent military historian Edward M. Coffman, “a large modern army ready to wage global war against the Germans and the Japanese.”

Coffman’s superb The Regulars: The American Army, 1898-1941 (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2004, 517 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover) is the long-awaited continuation of his 1986 study The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784-1898. This new, superbly researched, and riveting study chronicles the evolution of the U.S. Army from its emergence as a force used to conquer and control a new colonial empire to the eve of American entry into World War II. In many respects, Coffman has written a cultural and social history, as well as an institutional and campaign chronicle, of the U.S. Army during this period.

Coffman’s superb The Regulars: The American Army, 1898-1941 (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2004, 517 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover) is the long-awaited continuation of his 1986 study The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784-1898. This new, superbly researched, and riveting study chronicles the evolution of the U.S. Army from its emergence as a force used to conquer and control a new colonial empire to the eve of American entry into World War II. In many respects, Coffman has written a cultural and social history, as well as an institutional and campaign chronicle, of the U.S. Army during this period.

Anticipating war with Spain after the USS Maine was sunk in Havana Harbor in February 1898, the strength of the army surged from 28,000 to 104,000 officers and enlisted men, with an additional 200,000 volunteers. The military mobilization was not, however, accompanied by a similar increase in support capabilities. The result was that the army blundered its way through chaos and disease to a relatively easy victory over the Spanish.

After the Spanish-American War, the army became responsible for pacifying and policing numerous imperial possessions including Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Hawaii, and Alaska. Two interesting chapters, “The Colonial Army” and “Life and Training in the Philippines,” cover army service in these exotic locales.

One of the most important chapters in this study is “Enlisted Men in the New Army.” Myriad facets of the soldiers’ military experience—to include terms of and reasons for enlistment, recruit quality and literacy, training, duties, pay, living conditions, religious services, discipline, race relations, and their families—are described in detail. According to Coffman, the statement made by a secretary of war in 1889 pertaining to soldier enlistment was still relevant during this period: “To the colored man the service offers a career; to the white man too often only a refuge.” Noncommissioned officers were frequently motivated not only by pay raises, but also by “privileges, allowances, and dignity.” Numerous anecdotes appear in this chapter, as they do throughout the book.

Other chapters chronicle major military reforms in organization and professional education, highlighting curriculum at the U.S. Military Academy (West Point), the branch and service schools, the General Service and Staff College, and the War College. The development of military technology in the combat arms, including mechanization and aviation, is also recounted and assessed. Coffman labels these and other reforms as the “managerial revolution” that helped prepare the army for World War I.

The second half of this volume contains chapters on U.S. Army participation in “the war to end all wars”; the glacial promotions and doldrums of soldiering during the interwar years, at home and in “Pacific outposts”; and finally, “Mobilizing for War.”

Coffman, a renowned scholar of American military history, conducted research and collected material for this study for decades. He interviewed and sent questionnaires to scores of officers and enlisted men and their families from the pre-World War II era and used this priceless information, plus memoirs and letters, to include in each chapter riveting vignettes from their own experiences. Coffman also follows the careers of many officers, including Marshall, MacArthur, Patton, Devers, Eisenhower, Bradley, and others less prominent, in the decades leading up to World War II.

The history and evolution of the army from 1898 to 1941 is a reflection of American social, political, and technological factors, shaped in large measure by its officers and men. This easy-to-read, enthralling collective biography of the U.S. Army is impeccably researched and a model of military history.

Recent and Recommended

A Question of Loyalty: Gen. Billy Mitchell and the Court-Martial That Gripped the Nation, by Douglas Waller, HarperCollins, New York, 2004, 384 pp., illustrations, source notes, selected bibliography, index, $26.95, hardcover.

Aggressive, competent, self-promoting, and intolerant of inefficiency, U.S. Army Air Service Brig. Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell was a visionary and a showman who thrived on controversy. During the post-World War I military retrenchment, Mitchell fought for an independent air force and goaded the Navy into testing the ability of aircraft to sink large ships. It seemed to be a showdown between air power and sea power, innovation against tradition. Mitchell’s challenge was proved by the aerial bombing and sinking of the battleship Ostfriesland in 1921. Outspoken and unorthodox, Mitchell’s appointment as assistant chief of the air service was not renewed in 1925, and he reverted to the rank of colonel. He was reassigned to the Texas hinterlands, but was buoyed by the support of the press and air service veterans.

After naval aviation tragedies in September 1925, Mitchell responded by declaring them to be “the direct result of the incompetency, criminal negligence, and almost treasonable administration of the national defense by the Navy and War Departments.” While Mitchell may have thought this would propel him back into the limelight, he was charged with insubordination and conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline and court-martialed. The sensational trial resulted in Mitchell being found guilty on all counts and basically forced into retirement. Author Douglas Waller, using newly discovered diaries, letters, and other documents, has written a riveting biography and a dramatic record of the court-martial of this apostle of air power.

In Brief

The Battle That Stopped Rome: Emperor Augustus, Arminius, and the Slaughter of the Legions in the Teutoburg Forest, by Peters S. Wells, W.W. Norton, New York, 2003, 256 pp., chronology, maps, appendices, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in ad 9 is not well known today, but it is one of the most decisive military engagements in world history. A chieftain named Arminius led “barbarian” Germanic warriors and ambushed and wiped out three Roman legions in north-central Germany. This massacre had far-reaching consequences. Emperor Augustus abandoned his plans to conquer and colonize Germany, and he halted expansion at the Rhine River. Until recently, the only information about this battle came from brief references in Roman and Greek works. In 1987, archaeologists discovered the actual site of the battle at Kalkriese, near Osnabruck, Germany. Author Peter S. Wells has chronicled the events leading to the battlefield’s discovery. More importantly, he has used surviving Roman texts and archaeological evidence to produce compelling accounts of this seminal clash, from the perspectives of both the Romans and the Germans. The result is a fascinating narrative, detailed but written for the general reader, of this cataclysmic battle that left some 18,000 Roman legionnaires dead and dying in the blood-soaked mud of northern Europe.

Fort Ticonderoga, by Carl R. Crego, Arcadia, Charleston, SC, 2004, 128 pp., illustrations, maps, $19.95, softcover.

Fort Ticonderoga, by Carl R. Crego, Arcadia, Charleston, SC, 2004, 128 pp., illustrations, maps, $19.95, softcover.

Fort Ticonderoga was known as the “key to the continent” and the “Gibraltar of the north” during the 18th century because it controlled, at the borderlands of the French and British colonies in North America, the portage between Lakes George and Champlain. This area was also strategically important because it was the nexus of north-south (on the Hudson River) and east-west (by trail) transportation and communication routes in New England. Originally built by the French in 1755 and called Fort Carillon, Fort Ticonderoga played a key role in both the French and Indian War (1754-1763) and the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Afterward, Fort Ticonderoga fell into ruins, became a tourist attraction, and was restored beginning in 1908. This fascinating volume is a pictorial history of Fort Ticonderoga using mainly rare and vintage postcards. From its construction to the British storming of the fort in 1759, to its capture by Colonels Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen in 1775, through its modern restoration, this superb book traces the evolution and significance of an important American landmark.

Reflections of a Civil War Historian: Essays on Leadership, Society, and the Art of War, by Herman Hattaway, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2004, 254 pp., footnotes, index, $44.95, hardcover.

Reflections of a Civil War Historian: Essays on Leadership, Society, and the Art of War, by Herman Hattaway, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2004, 254 pp., footnotes, index, $44.95, hardcover.

Professor Herman Hattaway is the consummate Civil War historian. He has devoted his life to the scholarship of the War Between the States and to mentoring students in the pursuit of greater understanding of this seminal conforce them to give up the gold-rich Black Hills area. These efforts culminated in the destruction of much of Lt. Col. George A. Custer’s 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, June 25, 1876. The army then concentrated on subjugating, disarming, and punishing Indians, including those already on reservations. Part of this mission was given to the Powder River Expedition, commanded by Brig. Gen. George Crook, and including Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie’s 4th Cavalry and other units. Departing Cantonment Reno on November 22, 1876, Crook’s column began searching for Indians in their winter villages, where they were most vulnerable. A few days later, the army located and destroyed Northern Cheyenne Chief Morning Star’s 173-lodge village in a day-long, touch-and-go battle. While the engagement itself was somewhat minor, it had long-term ramifications, encouraging the Northern Cheyenne and Sioux to surrender the following spring. Noted National Park Service historian Jerome A. Greene conducted extensive research to write this balanced, fast-paced account of a chaotic Indian campaign.

Meuse-Argonne Diary: A Division Commander in World War I, by William M. Wright, edited by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2004, 174 pp., illustrations, maps, sources, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Meuse-Argonne Diary: A Division Commander in World War I, by William M. Wright, edited by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2004, 174 pp., illustrations, maps, sources, index, $29.95, hardcover.

There were 42 divisions, 29 of them in the front line, in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in Europe on November 11, 1918, the day the Armistice ended World War I. The four divisions considered the “best” were the 1st, 2nd, 42nd, and 89th. Maj. Gen. William M. Wright commanded the 89th Division, a national army division composed largely of conscripts from Kansas, Missouri, and Colorado, during the last two months of the war. Under his command, the 89th Division fought in the St. Mihiel offensive and advanced to a depth of almost 20 miles. The 89th Division was continuing offensive operations as part of the Meuse-Argonne campaign when the war ended. Wright is believed to have been the only AEF division commander to keep a personal journal, in which he candidly chronicled his perceptions of the war, the AEF decision-making process, his superiors, and his subordinates. Professor Robert H. Ferrell has superbly edited Wright’s journal, interspersing it with later comments from one of his regimental commanders. Wright’s journal provides an interesting glimpse into the higher levels of command of flict. This fascinating volume is an anthology of 13 of Hattaway’s Civil War essays, divided into three sections: “Leadership and Command,” “Society in Wartime,” and “The Art of War.” It is obvious that military leadership has been the focus of much of Hattaway’s studies, and “Civil War Leadership,” for example, is a perceptive collective biography of Southern and Northern generals. Other topics include religion in warfare, military balloon operations, and the evolution of tactics during the Civil War. All of the essays here are interesting and of a uniform high quality. This volume makes an outstanding contribution to Civil War scholarship, and is well worth the modest investment of time and money it requires.

Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri, 1862, by Bruce Nichols, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2004, 264 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover.

Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Missouri, 1862, by Bruce Nichols, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2004, 264 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover.

Missouri, loyal to the Union and occupied by Northern troops, was the scene of brutal fighting during the Civil War. Southern sympathizers, known variously as “partisans,” “irregulars,” and “bushwackers,” conducted low-intensity warfare to defeat the U.S. Army forces and destroy their means of support in Missouri, especially in 1862. Cartographer Bruce Nichols chronicles this guerrilla campaign, focusing on “which southern partisan leaders and groups operated in which areas of Missouri, how they operated and how their warfare evolved.” He relates “seemingly isolated incidents to other incidents to show patterns and chains of events.” To accomplish this goal, Nichols presents these operations chronologically and geographically, with chapters covering each three-month season of 1862 and each of four quadrants of Missouri. The result is a detailed, fast-paced, descriptive catalogue of guerrilla operations, through which colorful characters like William C. Quantrill, Joseph O. Shelby, “Bloody Bill” Anderson, and Cole Younger cut a wide swath. This fine, well-illustrated study helps one understand Civil War guerrilla motivation and operations in the West.

Morning Star Dawn: The Powder River Expedition and the Northern Cheyennes, 1876, by Jerome A. Greene, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2003, 304 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover.

In the spring of 1876, the U.S. Army began military operations to intimidate the Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne Indians and the AEF during the “war to end all wars.”

Hitler’s Admirals, by G.H. Bennett and R. Bennett, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2004, 248 pp., index, $29.95, hardcover.

Hitler’s Admirals, by G.H. Bennett and R. Bennett, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2004, 248 pp., index, $29.95, hardcover.

Shortly after Grossadmiral Karl Donitz surrendered Germany in early May 1945 and ended the European phase of World War II, a British Admiralty mission arrived in Flensburg. Its task was “to interrogate senior officers in the German Admiralty . . . [and] obtain details of technical development and equipment from the appropriate departments of the German navy.” Written interviews were conducted with a number of senior German naval officers. Selections from these 1945 essays are cobbled together in 12 thematically oriented chapters. From “The Prewar Period” and “Operation Sea Lion” to “Decision in the Mediterranean, 1942-1943” and “Fortress Germany and Unconditional Surrender,” the German admirals’ perceptions are presented and compared in each chapter. The defeated German admirals, through their own words, provide insight into the Third Reich’s Navy, its leaders, and its operations during World War II.

A Good Deal of Hell: Letters from a Chasseur a Pied, edited by Joshua Brown, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2003, 336 pp., illustrations, maps, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover.

A Good Deal of Hell: Letters from a Chasseur a Pied, edited by Joshua Brown, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2003, 336 pp., illustrations, maps, bibliography, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Robert Pellissier was born in France in 1882, migrated to the United States as a child, and earned a doctorate from Harvard in 1913. Only weeks after the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Pellissier left the comfort of his Stanford faculty position and traveled to France to enlist in the French Army. After a short period of training, he was sent to the mountainous Vosges area of Alsace. His numerous letters and diary entries, compiled by a descendant, reveal detailed observations and perceptive comments, many contradicting stereotypes of the French Army. On the one hand, soldiering, even in wartime, was “mainly monotonous drudgery”; shortly afterwards, one of Pellissier’s comrades was killed in the trenches: “there was a death rattle, the gurgling of a hemorrhage, then he rolled over on one side and remained lifeless.” Pellissier soldiered well, and his maturity helped him persevere stoically in the trenches – until a German machinegun drilled his chest and killed him in August 1916. Although he detested the insanity of war, a sense of duty and loyalty compelled him to return to and defend France, which cost him is life. Pellissier’s example is worth emulating, and this book deserves a wide readership.

America’s War with Spain: A Selected Bibliography, by Anne Cipriano Venzon, Scarecrow Press, Lanham, MD, 2003, 224 pp., $65.00, hardcover.

American participation in the 1898 Spanish-American War propelled the United States veritably overnight from being a minor player to a major participant in international affairs. This volume is a select bibliography of books, articles, and dissertations covering myriad aspects of the Spanish-American War, as well as its direct aftermath, the 1899-1902 Philippine Insurrection. In addition to general works, studies about foreign relations; biographies, memoirs, letters, and diaries; U.S. Army; U.S. Navy; press and public opinion; medical and sanitary conditions; relief efforts; black Americans; anti-imperialism; literature; music; and others are described and listed. America’s War with Spain is a worthwhile research tool for the student and historian of this watershed American military campaign.

Voices from the Korean War: Personal Stories of American, Korean, and Chinese Soldiers, by Richard Peters and Xiaobing Li, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2004, 312 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, selected bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover.

“I have both good and bad memories of my experiences in Korea,” recalled Herman G. Nelson, “but I sure wouldn’t want to go through all of that again.” Nelson served as a U.S. Army private first class in an 8-inch howitzer unit in Korea, 1950-1951, and was one of 21 Korean War participants—13 American, 4 Chinese, and 4 Korean—who provided reminiscences for this anthology. After an informative overview, the first-hand accounts are divided into five sections: “Many Faces, One War”; “Chosin Accounts”; “On the Front Lines”; “Behind the Front Lines”; and “POW Camps: North and South.” These individual stories are of varied quality, length, and interest. Many of the accounts are mundane, but those from the Chosin Reservoir, POW camps, and Chinese officers are the most interesting. These narratives were collected in the late 1990s, almost a half-century after the events described occurred. The editors recognize that “memory, of course, is not infallible, especially after so many years have passed,” advice the reader should consider when perusing this book.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments