By Alan Davidge

One of the most important tasks for Allied troops after the D-Day landing was to seize the city of Caen, nine miles behind Sword Beach. The plan was to take it the same day, but progress was so slow that German troops were able to establish strong defenses around the city, making it impregnable for many weeks. The Allies then prioritized the consolidation of the divisions that had landed on the five D-Day beaches into a secure beachhead in preparation for a breakout inland and to facilitate the U.S. capture of Cherbourg at the tip of the Cotentin peninsula. Once liberated, Cherbourg would become the main port for the supply ships needed to support troops in their fight across Western Europe.

Taking Caen remained a primary objective for the British and Canadian armies, keeping most of Hitler’s strongest panzer divisions occupied defending it and depleting their strength, so that other Allied units could concentrate on laying the foundations for victory in Normandy.

It was mid-July when Caen was taken and its German occupiers forced out to the south and southeast of the city. By this time much of western Normandy was in American hands, and the final details were in place for Operation Cobra, the breakout from the beaches. The cost had been high, however, with the beautiful medieval city in ruins and littered with the bodies of British, Canadian, and German troops. It had also become a graveyard for 3,000 French civilians.

There were a number of important centers behind the beaches which had to fall into Allied hands as soon as possible after D-Day to facilitate the advance into France and beyond. Carentan in the west, between Utah and Omaha Beaches, where the fighting is well documented in the Band of Brothers stories, fell to the 101st Airborne after bloody fighting during the period June 10-12, and this linked the U.S. divisions which had landed on the two beaches. The historic city of Bayeux, behind Gold Beach, was taken by British troops the morning after D-Day, but Caen was a prize which held the key to the interior with roads providing access to all points of the compass and the River Orne bisecting the city west to east. The area around it was sufficiently flat and low-lying to build temporary landing strips, and furthermore it had an airfield of its own, at Carpiquet on the western perimeter.

Given its importance, it would be fair to assume that preparations for the capture of Caen would have received a priority similar to other key objectives such as the storming of the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc by U.S. Rangers or Operation Tonga, which involved the silencing of the Merville Battery, and the capture of Pegasus Bridge by the British 6th Airborne. In his planning, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery failed to consider this, and right from the start the capture of Caen on D-Day appeared a very ambitious undertaking. The ability to hit its German occupiers hard with armor as well as infantry would be challenging at best, and there was no directive to prioritize the exit from the D-Day beaches by the tank regiments which would be essential in tackling the German panzers believed to be in the vicinity of the city. The task of capturing Caen was given by Montgomery to the British 2nd Army under Lieutenant General Sir Miles Dempsey, who had three armored divisions at his disposal plus a number of infantry divisions and the Canadian 1st Corps.

One factor which was to help the British and Canadian invasion in this area, and of which they were unaware, was the chaotic organization of the German high command and the fact that no major decisions could be made without Hitler’s approval. His two key field marshals in Normandy were Erwin Rommel and Gerd Von Rundstedt, and both had different views on how to stop the inevitable invasion when it took place. Rommel believed in deploying his powerful panzer divisions to the coast immediately, whereas Rundstedt wanted to keep most of the troops back until the Allied plan was clear and then defeat the enemy inland. Rommel famously said that if the invading troops were not defeated in 24 hours, it would be the end of the war for Germany.

Hitler attempted a compromise by reallocating responsibilities for the main panzer divisions, but the result was too few in the central reserve to be of use to Rundstedt and not 6thenough near the coast for Rommel. Personality clashes and personal ambitions among senior generals also slowed down the operation of key decisions, and unlike the senior team assembled by General Dwight D. Eisenhower as supreme commander, albeit with a few personality clashes of its own, there was no clear, workable process of delegation among the German commanders.

In the opinion of the British historian Antony Beevor, the only way the British 3rd Infantry Division could have reached Caen in a single day would have been to send at least two battle groups, each comprising an armored regiment and an infantry battalion, immediately after landing on Sword. Ideally, the infantry would travel by armored personnel carriers, which they didn’t have at the time. Unlike the Germans, the British had no integrated armored infantry that could work closely with tank units.

However, there was a plan to reach Caen on the afternoon of June 6—but as the day progressed, factors beyond British control, exacerbated by lack of foresight made it look increasingly impossible. Had the British troops even reached the city, they could well have been outgunned by the three elite divisions, 21st Panzer, Panzer Lehr, and 12th SS Hitlerjugendpanzers, which had been swift getting into position to mount a strong opposition.

The plan was for the British 8th Infantry Brigade to seize the fortified Périers Ridge, five miles inland. Then the 185th Brigade—with three infantry battalions, but only one armored regiment—would pass through them and on to the city of Caen. The 2nd Battalion King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (KSLI) would meet the Staffordshire Yeomanry near Hermanville, less than a mile from the coast and lead the advance, supported by infantry battalions from the Royal Warwickshire and Royal Norfolk Regiments.

The three infantry regiments duly arrived at Hermanville at 11 a.m., but the tanks of the Shropshire Yeomanry failed to appear. The foul weather that had hampered the invasion had also brought exceptionally high tides to Sword Beach, severely reducing its width and causing horrendous traffic jams at the exits. After this delayed start, the tanks then encountered minefields that prevented them traveling cross-country and confined them to already congested roads, some of which had been the recipients of the early Allied pre-invasion bombing that had missed the bunkers on the beach and caused carnage inland.

To make matters worse, the 8th Infantry encountered stiff opposition when it reached the strongpoint codenamed Hillman on Périers ridge and needed backup. Their forward observer, who could have called for support from the 15-inch guns of the British battleships Ramilles and Warspite anchored offshore, had just been killed. That meant the struggling Staffordshire Yeomanry, on its way to joining the infantry, was asked to send a squadron to blast holes in the Hillman defenses instead. If the rest of the regiment ever got to Caen this meant that their commander would have even less firepower, but he reluctantly agreed to the request.

British reconnaissance had seriously underestimated Hillman’s strength and complexity. If this had been understood in advance and knowing it barred the way to Caen, perhaps a strategy could have been put in place to ensure it was neutralized early.

The understrength but determined infantrymen continued toward Caen with the Shropshires leading the way, successfully skirmishing with isolated groups of Germans en route. But the Norfolks who followed them suffered 150 casualties from the Hillman guns before it was neutralized. The Shropshires cleared the small town of Biéville, before stopping at Lebisey Wood at 6 p.m., only three miles from the city. Here their remarkable first-day contribution to the liberation of France came to a grinding halt. Waiting for them were elements of the 21st Panzer Division. Having sustained 113 casualties—and fully aware of the consequences of trying to take on German tanks without serious armored support—they dug in for the night.

Elsewhere, in the gap between the Canadian 3rd Division’s landings on Juno Beach to the west and the right flank of the British troops on Sword another panzer unit mounted a counterattack, heading for the coast. The commander of the Staffordshire Yeomanry, Lt. Col. J.A. “Jim” Eadie, had anticipated this and positioned three troops of Sherman Firefly tanks, which had gotten through the coastal traffic jam, in their path. Thirteen Mk IV tanks were destroyed in minutes and the rest retreated back to Caen.

This encounter was a glimpse of things to come for the panzer divisions. Their Mk IV tanks were formidable, as were the Tigers with their 88mm guns. German commanders felt they could dominate the battlefield and destroy any Shermans in their path. But the Sherman had evolved into the Firefly with a 17-pounder antitank gun. Coupled with its better maneuverability, the Allies now had a tank that, in skilled hands, could take apart its most fearsome opponents.

The British armored divisions had several more surprises for the Germans. In addition to adapting the Sherman to carry a game-changing gun, several other tanks were transformed for specialist roles. Beach defenders were shocked when what looked like floating bath tubs rolled up on the sand and transformed into Sherman tanks. These were the Duplex Drive tanks with protective screens that facilitated amphibious landings. Flail tanks with rotating drums in front whipped chains across minefields to clear them for the infantry to follow. Further inland, those troops holding up infantry advances in reinforced concrete bunkers soon lost their feeling of security when the troops summoned up a Crocodile—a Churchill tank mounting a flamethrower with a range of 80 yards. These specialist machines were the brainchild of Major General Percy Hobart and known to the troops as “Hobart’s Funnies.”

After a disappointingly slow start, the British troops who survived the Sword Beach landings had their first sleep on French soil and hoped the next day would go according to plan. But for the inhabitants of Caen it had been a lot worse—as an exhibition in the Caen Memorial museum now chronicles.

First had come the leaflet drop, warning them of imminent air raids and advising them to disperse into the countryside. Few had time to respond before the first British air raid in the morning. In the afternoon it was the Americans, then three more raids hitting populated neighborhoods and the city center. By the evening, Caen was ablaze. The targets had been the four bridges over the Orne, but these remained intact.

After four years of occupation, it seems reasonable that the French could have expected and accepted the odd friendly fire incident and the shocks that came from being caught in the crossfire before they saw the end of the hated Boche. But this bombing was without precedent. Nobody had taken the trouble to explain or justify that the Allied bombing strategy was not so much about killing Germans as hitting strategic targets. Bridges, railways, crossroads, anything that could slow down the enemy, were the main focus of the Allies’ so-called Transportation Plan and from thousands of feet in the air, the only way to hit these targets was to plaster the surrounding area with as many bombs as possible. This was supplemented with 15-inch shells from ships in the English Channel that could not see their targets, but had to hope the coordinates they had been given were correct. There were only 300 Germans in Caen at the start of D-Day, and by the end of June 7, there were 800 French civilian dead, thousands injured, and the city lay destroyed. The French civilians were not to know that ordnance would continue to rain down on them for a further six weeks of horror, resulting in a total of 3,000 civilian deaths before the enemy was on its way. Not exactly the Libération of their dreams.

The Allied plan prescribed the bombing of any center of population that was considered a strategic target. Another local casualty was Aunay sur Odon southwest of Caen, population 800 and a major crossroads linking Bayeux, Caen, Falaise, and Vire. Fearing it would be critical to the supply of German reinforcements to Caen, it was bombed the nights of June 12 and June 14, killing 25 percent of its residents and completely destroying the town.

With the Shropshire Light Infantry and the remainder of the British 185th Infantry Brigade held up at Lebisey Wood by the 21st Panzer on the morning of June 7, it was now the turn of the Canadian 3rd Division, moving inland from Juno Beach, to attempt a breakthrough into Caen. Their objective was Carpiquet airfield to the west of the city. Here they found the fanatical, young Hitlerjugend of the 12th SS Panzer Division in their path, ready to convert the ideology they had been consuming since childhood into action.

The next few days saw bloodthirsty duels between the two divisions—attacks, counterattacks, villages lost, then gained and scenes reminiscent of World War I. By the end of their first week in Normandy, the Canadians had suffered 3,000 casualties, but they were winning the war of attrition. The Luftwaffe were now a spent force in the war, so the men enjoyed unchallenged air support, and whereas fresh troops and supplies could arrive daily to replace them via the landing beaches and the developing Mulberry harbor at Gold Beach, the German army would find it more challenging to refresh its front line. Furthermore, Hitler’s orders were to stand and fight rather than make tactical withdrawals, a strategy preferred by Rommel and his other generals who were in the thick of the action and therefore had a better impression of how the invasion was progressing.

Montgomery had to revise his plan as taking Caen head-on was no longer practicable. His answer was Operation Perch, which involved the British I Corps under Lt. Gen. John Crocker in the east and XXX Corps under Lt. Gen. Gerard Bucknall in the west launching a joint pincer attack to envelop the city. At the same time, the panzer divisions were planning counterattacks outward from Caen, causing stalemates and more battles of attrition when both sides met. Crocker’s I Corps in the east was halted south of the Orne by 21st Panzer, and in the west, Panzer Lehr put up strong resistance against XXX Corps. But here Montgomery had more success directing the British 50th Infantry Division and the tanks of the 7th Armored, the “Desert Rats,” out from Bayeux to Villers Bocage as the right flank of his pincer, which resulted in a ferocious battle at Tilly sur Seulles that left the town in ruins.

Then, to the surprise of the 7th Armored, a gap opened up before Villers Bocage as units of Panzer Lehr had been moved eastward to defend against attacks by the Canadians, creating the impression that there was now a clear path to Caen. Bucknall saw the opportunity and seized it. Tanks and troops entered the town in triumph at 8 a.m. on June 13, cheered by ecstatic French residents, and then moved up to Hill 213 to get a clearer view of the route into Caen. But they were not alone. Watching them from beside his Tiger was Michael Wittman, “The Black Baron,” Germany’s most celebrated destroyer of enemy tanks with a total of 119 kills achieved on the Eastern Front alone. A brilliant team leader, Wittman was just as dangerous when he worked alone.

With no other tanks for support, Wittman headed for the town. The confident British crews had stopped for maintenance and breakfast, leaving their vehicles unguarded. Wittman then proceeded to take out 12 halftracks, a series of lightly armored Honey tanks, and three Cromwell tanks, sweeping swiftly into the center of town and out again to collect reinforcements. He returned in the afternoon with more Tigers and MK IVs, destroying a row of Fireflies, Cromwells, and Bren Gun carriers. A number of German tanks were destroyed in the process, but at the end of the day the town was back in German hands and the British 7th Armoured Division, heroes of El Alamein, had lost 25 tanks, 14 carriers, 14 halftracks, and several hundred dead.

The German occupiers of Caen had now effectively formed a solid ring around the city. It could have been worse, however, as Hitler was still taken in by the D-Day deception plan Operation Fortitude, believing the main Allied thrust would come across the English Channel to Calais with Gen. George S. Patton’s fictitious First Army Group, so he had to keep all of his Atlantic Wall protected. In addition, such was the Allied command of the air that troop trains provided an easy target. Most German movement toward Normandy had to be by road which would take longer. Intelligence from the French Resistance on troops moving by road was also acted upon, so they would be depleted in numbers when they finally arrived.

Montgomery took significant criticism from day one for failing to capture Caen, some of which he deflected toward Dempsey to whom he had delegated the task, but strategically he was gaining some ground. His subsequent efforts in containing the Germans around Caen were certainly keeping the panzers away from the U.S. army further west, which had suffered a traumatic landing on Omaha Beach and now had its hands full, fighting through the hedgerows to cut off the Cotentin Peninsula and capture the major city of St Lo. Montgomery was also putting so much pressure on his old desert adversary Erwin Rommel that the German field marshal could not release any of his panzer divisions to create an operational reserve.

On June 18, Montgomery ordered Dempsey to put in place a pincer plan with the main thrust from the Orne bridgehead in the east, taken by the British 6th Airborne on D Day, but this was reconsidered when it appeared there would not be enough space to assemble all the troops and tanks required. The emphasis would have to come again from the other side of Caen. Despite the success of the sudden overnight attacks by the paratroopers and gliders on D-Day, the subsequent German counterattacks had prevented the enlargement of the Orne bridgehead until weeks later.

At about the same time, Rommel was ordered to mount a counterattack between Caumont, west of Caen, and the city of St Lo, which would separate the U.S. troops from the remaining Allied forces, and head for the coast, recapturing Bayeux in the process. This attack would comprise units currently moving toward Normandy: 2nd Panzer Division and five SS panzer divisions, namely the 9th and 10th from the Eastern Front plus 1st SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler and 2nd Das Reich from southern France. Because of the Allied air threat, they traveled by road where some were attacked by the French Resistance. The SS, in reprisal, carried out atrocities en route among the French population with Das Reich hanging nearly 100 suspected résistants in Tulle before wiping out the population of Oradour sur Glane the next day.

On June 19, the weather added more misery. The worst storm for many years hit the Normandy coast, grounding bombing and strafing missions from England, sinking ships in the Channel, and destroying the artificial Mulberry harbor at Omaha Beach. Its counterpart at Gold Beach was also damaged. Supplies to troops were delayed, as was Montgomery’s plan. The Germans seized the opportunity to hunker down and recover for a couple of days until the storm blew itself out. General Eisenhower shared the frustration but with a sense of relief. His decision to launch D-Day on June 6 had been a serious gamble because of the weather. If he had decided to defer it, the next date when tides and other conditions would be right was June 19.

Montgomery’s new plan, code named Operation Epsom, was now to kick off on June 26, four days later than scheduled. Operation Martlet, an attack on the Rauray Spur to the west of Caen where panzers were taking advantage of the high ground, would take place a day before that. With this threat contained, the main thrust would curl around the city, cross the Odon, and finish up on the high ground south of Caen at Bretteville sur Laize on the road to Falaise. If all went well, the Canadian 3rd Division would attack north of Caen, then move southwest and finally take the coveted and highly strategic Carpiquet airfield.

The main role in Epsom was assigned to the 60,000 men of VIII Corps, who had just arrived in France under Lt. Gen. Sir Richard O’Connor. Among them was 28-year-old Harold Sykes. Working in farming, a reserved occupation, he could have stayed safely at home, but his sense of duty had gotten the better of him. Fate had now placed him with the crew of a Mk 5 Sherman tank of the 2nd Battalion, Fife and Forfar Yeomanry, 29th Armored Brigade.

On June 14, having sailed from southern England on the 9th and awaiting orders to join the line, Harold with time on his hands penned a note home which he hoped would never be sent: “Dear Ma, Dad and sisters…I thought it would be a good opportunity to write this letter. It is intended to be a last goodbye as we do not know when the end will come so I wish to thank you for all you have done for me. You will not get this letter until something has happened to me….It was my wish that I went and I have had some happy times and do not regret it. It is only bad luck if something happens to me.. Your loving son, Harold.”

Three days later Sykes wrote a more cheerful note describing his impressions of France and sent it home. On June 20, while the storm in the English Channel was imposing a pause on Montgomery’s plans, he wrote again, thanking his “Ma” for the parcel he had received the day before, which contained some soap and the local newspapers. He complained about the army food and asked for some dried eggs and jam, if she could send him any. He finished with “One of the last things that I shall remember of the old country was the smell of fish and chips just before we embarked. What I could do with a plate now!”

At first light on June 25, Operation Martlet was launched to occupy the high ground around Rauray and the town of Fontenay le Pesnel so as to protect the right flank of the units which would spearhead Epsom. By dawn the next day, Fontenay was in British hands after some fierce fighting, but the Germans still held the Rauray Spur. Epsom went ahead as planned amid rain and poor visibility with a huge artillery barrage and with Harold and the 2nd Fife & Forfars supporting the 15th Scottish Infantry Division. The ground was boggy, and the weather prevented air support. Progress was slow, but the small town of Cheux was taken and Harold’s A Squadron with others of the 29th Armored Brigade worked around the town to Haut du Bosq, a hilly wooded area to the southwest.

It was a day of attack and counterattack, with the Germans still established in Rauray pouring shells into what was left of Cheux. In the smaller villages, fighting was hand to hand between Scottish infantry and panzergrenadiers. An armored reconnaissance squadron was sent forward to seek out the bridges over the Odon but penetrated no further than the high ground south of Cheux. It was a disappointing day for the British troops, many of whom had moved back to a position north of Cheux for a more secure night, but they were not to know that the force of their attack had persuaded Rommel that he could not contain them without moving more of his panzers that had been destined elsewhere behind the beaches.

The inhabitants of Cheux had already evacuated the town and begun the long refugee trail to a safer area near the Brittany border. Local historian Maurice Lajoie recalled, “My father, the baker, was killed on June 10. On June 12 everyone was ordered by the Germans to leave the town. My grandfather who was the mayor and all the other families left with their horses and charrettes in the direction of the Mayenne, not returning till September, when they found our town 80 percent destroyed. My mother gave birth to me at the end of October.”

At 4:45 a.m. on June 27, the British attack resumed, led by the 10th Battalion, Highland Light Infantry supported by Churchill tanks. Casualties were high, but by the afternoon the Odon had been crossed and a bridgehead established at Tourmaville. The panzers had also been cleared from Rauray. The Scots had been relieved by the 43rd Wessex Infantry Division, and progress had been made, but at a heavy cost.

The day had begun well for A Squadron, 2nd Fife and Forfars, being selected to follow the first infantry attack behind the Scots and the Churchill tanks. When these suffered heavy losses the squadron was ordered to change direction and give support. Lieutenant Brownlie’s lead tank was damaged, and Harold’s crew took over leading the advance right up to the panzers’ positions, destroying one and damaging another. Their gun took a hit, but that did not stop them from engaging the enemy with their .50-cal. Browning machine gun and grenades.

What happened next is only partially remembered by the survivors. Their tank was hit by a shell, caught fire, and then the ammunition went up. The sergeant and two crew members somehow got out, with wounds that would put them in hospital for weeks. For Harold and the driver, his close friend Stanley Thompson, the war was over. A month later, Mrs. Sykes received condolences from the chaplain who had overseen their burial service and from Harold’s lieutenant telling her that her son and Stanley had been laid to rest where they fell, by the roadside near a little ruined French village (Cheux), south of the church in a grassy bank, “which is forever England.”

On June 28, the battle resumed early with ferocious fighting to try and capitalize on the expensive gains of the day before. Allied troops gained an unexpected advantage when the Germans suffered the setback of losing their 7th Army commander Gen.Oberst Friedrich Dollman, who had overall responsibility for the invasion area. Following the successful American capture of Cherbourg two days earlier, he was dismissed by Hitler and rumor suggests he committed suicide. He was replaced by SS Oberstgruppenfuhrer Paul Hausser.

Grainville sur Odon was secured and held against counterattacks while the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders pushed a salient deeper into enemy territory. Eventually a key strategic point on the map, Hill 112, was seized by the infantry and reinforced by a unit of the 11th Armored Division—but uncomfortably so with German tanks in position on the opposite slopes. Further advance was put on hold as 2nd Army commander Lt. Gen. Dempsey received details of a planned German counterattack through ULTRA, intelligence gleaned by the communications decryption unit at Bletchley Park. He informed O’Connor, in charge of VIII Corps, that he would soon have to close ranks. A buildup of enemy troops and tanks gave further proof of an imminent attack, but improved weather allowed the Royal Air Force to come into the fray and remove some of the opposition before it could get started.

The expected counterattack materialized on the afternoon of June 29 with the recently arrived 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions playing a lead role. Dempsey responded with a tactical withdrawal from some of the frontal positions, including Hill 112, in order to reinforce the bridgehead on the Odon and keep hold of the higher ground at Rauray.

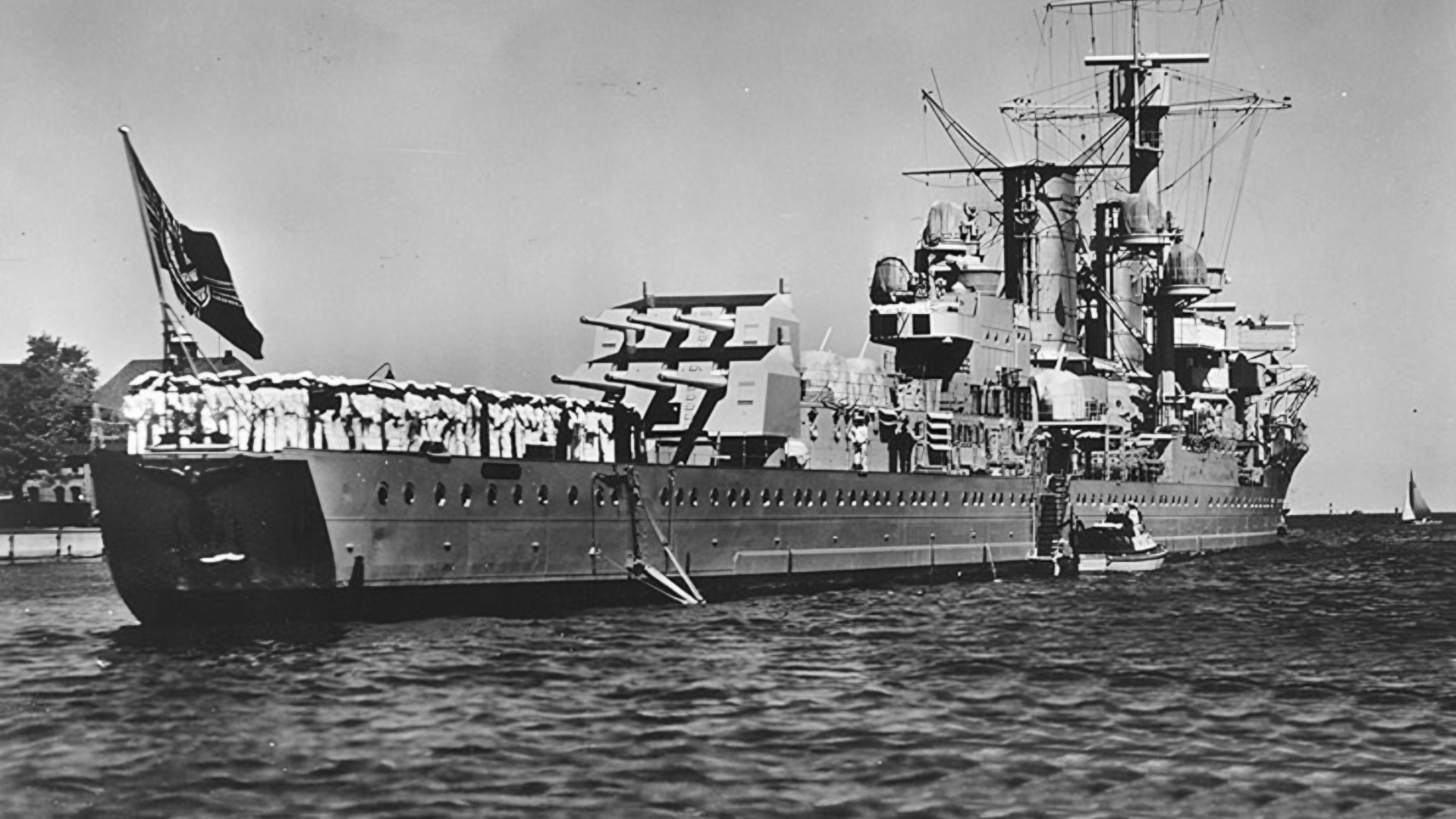

On June 30 the fog of war descended upon the battlefield, affecting troops and civilians alike. The 9th Panzer Division resumed the attack, and the 10th Panzer Division delivered a heavy barrage on Hill 112, then charged the summit only to discover that British troops had gone. Elsewhere there were costly individual encounters, forcing Hausser to call off counterattacks temporarily. Unaware of this, Dempsey decided to consolidate. Offshore, the guns of the battleship HMS Rodney began firing at small villages believed to be occupied by Germans, and in the evening 250 British heavy bombers destroyed the small town of Villers Bocage, also believing it to be occupied, but only French civilians were present.

Counterattacks recommenced the following day, but Dempsey’s line held firm except for a temporary incursion at Haut du Bosq. Casualties were high on both sides, and a British attack with flamethrowing Crocodile tanks provided a particularly painful conclusion to the day’s fighting.

Rommel’s decision to commit the last of his forces to containing the British advance without success in this battle for Caen now resulted in his requesting a tactical withdrawal to the River Seine, but Hitler refused.

Operation Epsom had cost more than 3,000 casualties on both sides and could have been seen as a stalemate, but its result should not be judged in terms of winners and losers. Despite the efforts of his troops, Dempsey was nowhere near his objective of Bretteville-sur-Laize, and the Canadians were still impatiently waiting to get their hands on Carpiquet airfield, but a cost-benefit analysis of events would put the Allies ahead. The Germans never recovered from their losses during Epsom and entered the next phase significantly weakened. Everyone knew this except for the Führer, and the all-time low in confidence felt by his senior staff became a contributory factor in the tragic assassination attempt the following month. With reinforcements and supplies arriving daily from across the English Channel, Montgomery, on the other hand, had the resources he needed to continue his drive into Caen, and by July 5, he had formulated his next plan, Operation Charnwood.

The Charnwood assault was to be launched at 4:20 a.m. on July 8, and this time Montgomery was back to tackling the city head-on. Crocker’s I Corps was assigned the task of attacking from the north with three brigades and the 3rd Canadian Infantry with hitting Carpiquet from the southwest. The city was defended by the experienced 12th SS Panzer Division in the center and the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division in the northeast, which would prove to be a much weaker unit.

During the late evening of July 7, the northern part of Caen was bombed massively by British Lancaster and Halifax bombers, followed by six squadrons of Mosquito fighter bombers. The huge guns of HMS Rodney and other ships anchored offshore then added to the destruction, but reports from troops on the ground signaled an enormous morale boost after weeks of slow progress as they assumed that this would end the German resistance once and for all. Unfortunately, in an attempt to avoid any blue-on-blue casualties the planes had been ordered to hold back a few seconds, and although some damage was inflicted upon the enemy, it was once again the French civilians who came off worse as 80 percent of the northern part of the city was destroyed.

The next day, July 8, British and Canadian forces entered a number of small villages north and west of Caen. Then, following attacks from American bombers and British Typhoon fighter bombers on visible German positions, they moved within sight of the city. The Canadians to the west suffered very strong opposition from the fanatical Hitlerjugend who had no qualms about following the Führer’s orders to fight to the last man. “We were supposed to die in Caen,” noted their commander, Col. Kurt Meyer. By nightfall the Allies were a kilometer from the heart of the city, unaware that during the night and against Hitler’s orders, the majority of German troops would make a tactical retreat to the south side of the river.

When the men eventually entered the city itself they were to find that the rubble would be more dangerous than the original buildings as it provided concealment, sniper hideouts, opportunities for mines and mortar teams and booby traps, as well as general obstacles to movement. Furthermore, there had been a five-hour gap between the bombing and the actual assault, which allowed the enemy time to occupy defensive positions. One effective, if unintended, result of the bombing was the destruction of several bridges, which had hitherto remained intact, by stray bombs, making it difficult for the Germans to resupply from the south side of the Orne.

Troops pushed forward into the city on July 9, and by noon the British 3rd Infantry, after decimating the 16th Luftwaffe Field Division, had reached the banks of the Orne. At 4 p.m., they met up with the Canadians in the center of the city, but it felt a hollow victory to many who had survived. The cost of the two days of Charnwood was 3,500 casualties, and half of Caen was still occupied.

The remaining Germans were rounded up and taken prisoner. Among them were the remnants of the 12th SS Panzer Division, the “Hitler Youth,” the young warrior athletes nurtured into an ideology that would not have seen them out of place in a Kamikaze squadron. One of the saddest indictments on how they were used to advance Nazism is illustrated by a comment from a British Tommy whose unit captured a group of Hitlerjugend. “We went through their pockets and instead of cigarettes we found bags of sweets.”

Despite their own suffering, the surviving French residents appeared through the dust and rubble to welcome the troops. The War Diary for the King’s Own Scottish Borderers remarked: “The ghostlike houses suddenly came to life as civilians began to realize we were entering the town. They came running out with glasses and bottles of wine.”

A month after D-Day, the northern half of Caen was now liberated, and the Canadians were at last occupying Carpiquet and its airfield. As the bulk of the Canadian 1st Army was still in England, Montgomery hoped that there would be reserves to call upon for the next stage in the liberation, but the British army was now at maximum strength, with the potential well of new recruits drying up. His plans from now on would have to minimize infantry casualties in particular. Not surprisingly, many German formations were a shadow of their former selves. The mighty Panzer Lehr could no longer operate as a division, and so many of the Hitlerjugend had followed their Führer’s orders and sacrificed themselves rather than surrender.

U.S. General Omar Bradley felt that the position which the British and Canadians had gained in Caen gave him the space to push ahead with the breakout from the beaches and the capture of the vital city of St Lo, which he eventually entered on July 18. Rommel, cognizant of the seriousness of this latest development, finally sent infantry divisions west to try and frustrate the American plans. As for the French, the partial capture of Caen, with all its death and destruction, gave them heart that the Allies were here to stay. On July 10, they raised their tricolor in the city, and on the 13th, held a parade with a Scottish piper playing “La Marseillaise.”

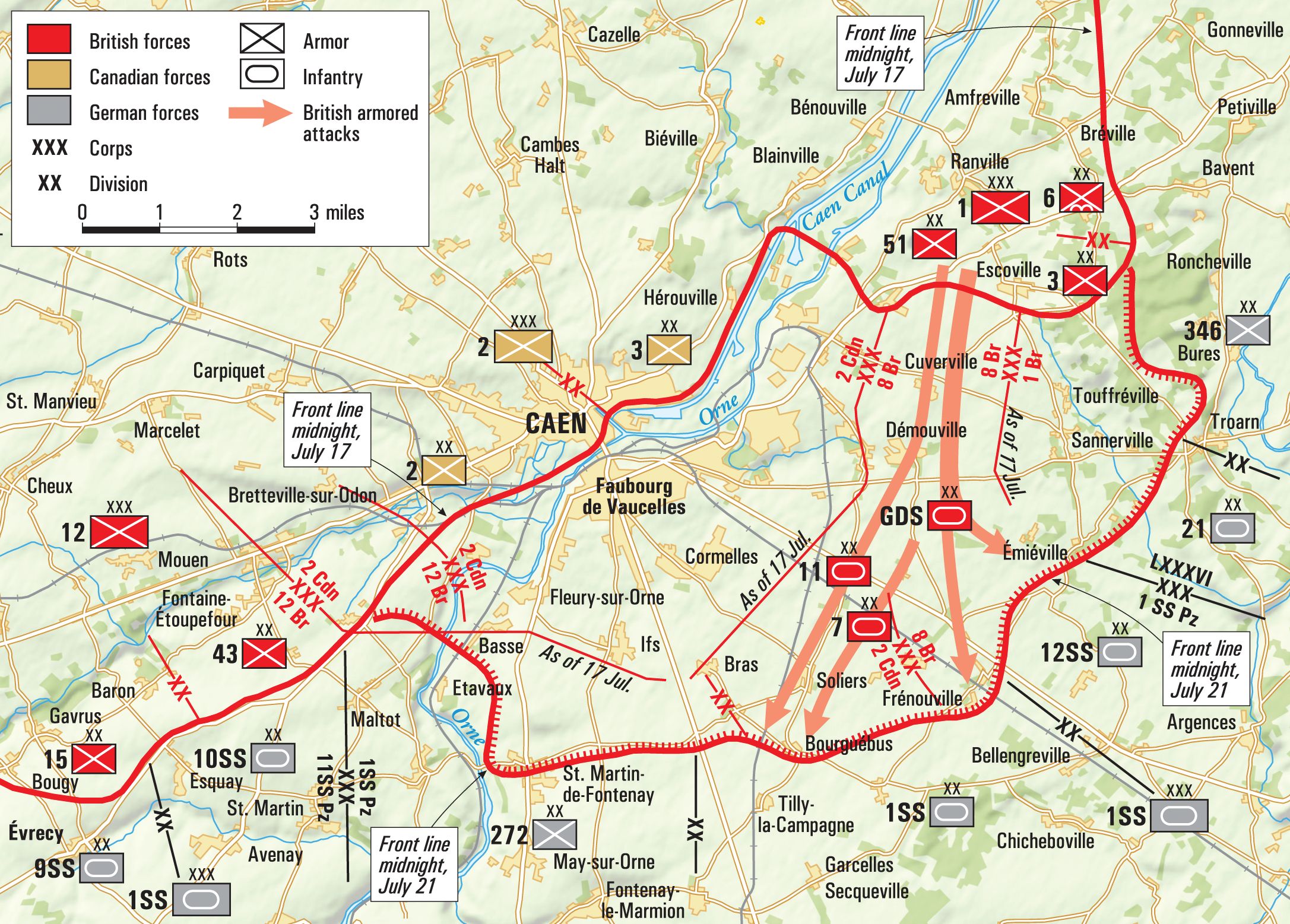

In order to complete the capture of Caen, Montgomery felt it important to consider it in the wider context of his Normandy objectives, and between July 10 and 13, meetings were arranged with Bradley, Lt. Gen. Guy Simonds of II Canadian Corps, as well as his own generals. His next advance would coincide with the U.S. breakout from the beaches, Operation Cobra, and involve a coordinated two-pronged advance on both Caen and the Verrieres-Bourguebus Ridge to the south of the city with a Canadian attack, Operation Atlantic, pushing south across the river and a major British armored advance from the Orne bridgehead to the northeast, Operation Goodwood. The timing would have the advantage of creating a useful diversion for Bradley, making it harder for any more German divisions to be released westwards to tackle his breakout.

The first task would be to secure the city south of the Orne, but the opportunity of taking the southern ridges beyond raised hopes of a breakout to the plains to the south to facilitate a push eastward toward Falaise. Montgomery did not expect to get this far but felt that the resources at his disposal for a tank battle in open country would, at the very least, seriously weaken the German forces to the point where retreat would be their only option in the following weeks.

Goodwood and Atlantic would commence on July 18, but a series of diversionary attacks around the River Odon (subsequently known as the Second Battle of the Odon) would start on July 15. It was important for these to divert attention from the Orne bridgehead on the east side to allow British armor to assemble for what was to be arguably the largest tank battle in British history. Montgomery would normally plan an assault with a good balance of infantry and armor, but the lack of replacements meant he had to limit his infantry’s involvement.

Operation Atlantic began as planned with heavy air support, and soon Colombelles and other industrial centers in the southeastern suburbs of Caen were in the hands of the 3rd Canadian Infantry. By the end of the day, several units had progressed to the southwestern outskirts at St. André. The subsequent consolidation the following day meant that the Battle for the city of Caen was effectively over.

Before Operation Goodwood could begin pontoon bridges had to be built across the River Orne and the Orne Canal south of the two bridges taken on D-Day to move armored vehicles eastward to the assembly area near Ranville. The British advance, consisting of three armored divisions (11th, 7th and Guards), started on time with a huge RAF bombing raid and smaller groups of planes hitting specific individual targets. From the 11th Armored Division, its 3rd Royal Tank Regiment led the attack with the 2nd Fife and Forfar Yeomanry following, and Harold Sykes’ former Lieutenant Brownlie leading his squadron. They were preceded by a creeping artillery barrage and made good progress on the flat terrain, ideal for a fast-moving tank battle.

The German defenses on the Bourguebus ridge, south of the Orne, were 10 miles deep and arranged in four lines. The tanks also had to cross two railway embankments. By the evening of the first day, losses were considerable, with the 11th Armored losing over half its tanks. The division was replaced by Canadians the following day, and some progress was made by capturing villages on and around the ridge. The next day was hampered by poor weather, and by the morning of July 21 Goodwood was called off.

Overall, Goodwood could be considered to be a success, gaining seven miles of ground and causing significant German losses but at the expense of thousands of troops and a great many tanks. The attrition of the panzers was continuing, meaning fewer units to frustrate Bradley’s breakout to the west. The British breakout, Operation Bluecoat, which started on July 30 closer to Caen after the withdrawal of the 2nd Panzer Division, was another beneficiary. From July 19, Caen was conclusively in Allied hands, and the bridgehead to its east had been widened so the city could expect no further trouble from the Führer. Ironically, the day after its liberation saw the attempt on Hitler’s life by his generals, which sent shock waves through the command structure of the German army.

The city of Caen, freed from its German occupation, would try to rise like the proverbial phoenix from the ashes of the Allied bombing. The Marshall Plan after the war would assist the French to get started, but some of its renovation began within days of its liberation, thanks to the work of the Royal Canadian Engineers who had arrived at Juno Beach on July 11 and headed straight for Caen to begin clearing a path through the rubble, defuse mines, and build new bridges across the river. Ostensibly this was for military purposes, but it was the first sign of hope for the city’s inhabitants who had seen nothing but destruction these past few weeks. Furthermore, some of these men spoke French and shared a cultural heritage.

The Canadian sappers cleared a path they called “Andy’s Alley,” after General Andrew McNaughton, also a civil engineer. It would officially become Avenue Triomphale, then Avenue du Six Juin. When they arrived at the River Orne, they started building five Bailey bridges. These prefabricated truss bridges were appearing all over Normandy and were strong enough to carry the weight of a tank. The first were named Monty’s, Winston, and Churchill bridges. When the engineers began building a large 50-meter span to connect the city’s Vendeuvre and Hamelin wharves, news arrived that their captain, Gilbert Reynolds, had just been killed so it was dedicated to him. Today it is the Pont Capitaine George Gilbert Reynolds. The role of combat engineers is often overlooked by historians, but they played an essential role in supporting Allied forces and indirectly in bringing back some normality for the civilians who had found themselves sharing the front line with them.

The Battle for Caen subsequently evolved into the battle for the Verrières/Bourguebus ridge, and much of the lead fighting would be done by the Canadians. Within a month, the remnants of the German army would be pushed eastward toward Falaise with the prospect of encirclement, capture, or being squeezed through the Chambois/Falaise pocket.

In trying to summarize the success or otherwise of the Battle for Caen, it is easy to focus on the failure to capture it on D-Day or on the death and destruction inflicted on both its population and its liberators as a result of the attempts to evict the Germans during the next six weeks. In truth, given the determination of the well-resourced Allies to occupy the European mainland and the desperate reaction of an experienced, well-equipped and highly trained enemy which knew it was fighting for survival, the Battle of Normandy was going to be a fight to the death wherever the two sides met. The fact that the immediate German D-Day restrictions kept the panzer divisions away from the western beaches and concentrated them around Caen meant that the city and its environs were where they were most likely to be forced to make their stand. The total destruction of St Lo in the western half of Normandy is further evidence that no center of population was going to be safe once the enemy had turned it into a fortress for defense.

If Caen had been taken on the first day, it could not be assumed that the subsequent battles would be fought cleanly and out in the open with fewer civilian casualties because Allied control of the skies made them very vulnerable in the field. A bigger mistake than failing to take Caen immediately may have been the actual bombing of the city without consideration for the lives of the thousands of French civilians living there, which also reduced the townscape to features that proved protective for the enemy and easier to defend. This was a serious error from both a human and a tactical perspective. If, in the dark days of 1940, Hitler had managed to establish a foothold on the south coast of England, it is difficult to imagine the RAF bombing civilians to drive out the invaders.

Whether Montgomery’s subsequent operations to seize Caen were an attempt to make up for his failure to capture the city on D-Day or a clever plan to contain the bulk of Hitler’s men in one area so that the rest of the liberation would be less hindered is debatable. It was probably a bit of both with the wily old opportunistic British warrior seeing the chance of turning a negative into a positive. The outcome was the attrition of an increasingly isolated German army which became even more vulnerable when, during the first week of August, the Allies were joined by General Philippe Leclerc’s French 2nd Armored Division from North Africa and the Polish 1st Armored Division. Whether by accident or good Allied planning, the onslaught by the Canadians and British in Caen had left the Germans weakened to a level from which they could not recover.

Today Caen is a vibrant modern city and cultural center with pavement cafés along the river, a top university, and the status of the capital of the Calvados Department. It also contains the largest World War II museum in Normandy, The Caen Memorial, a beautifully designed and well-resourced structure which leaves visitors in no doubt as to the sacrifices made by Caen’s residents and their liberators in the pursuit of peace and freedom in the summer of 1944.

Author Alan Davidge is a frequent contributor to Sovereign Media publications. He is a resident of Normandy, France, and is quite familiar with the campaign of World War II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments