By Nathan N. Prefer

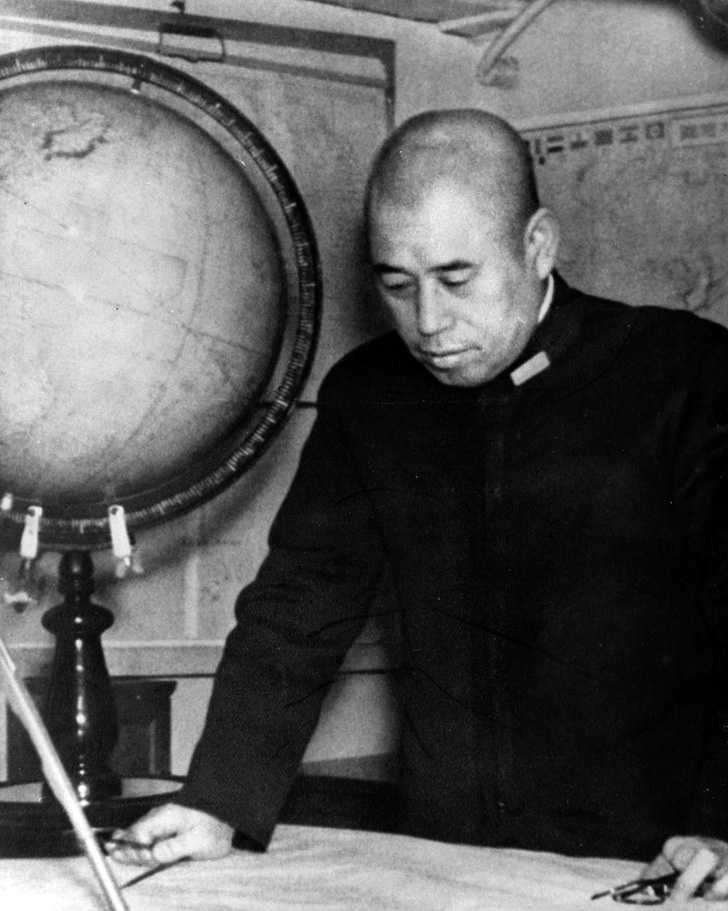

Reluctantly, Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto executed the Attack on Pearl Harbor and brought war with the United States.

For many Americans in late 1941 and early 1942, he was the most hated—and feared—man in the world. More than Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, or Josef Stalin. Many believed that he was just off the Pacific Coast with a huge fleet of warships, ready to pounce at any moment on United States soil. His name was Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, and he was the man who planned the attack on Pearl Harbor.

This dangerous man was born April 4, 1884, to schoolmaster Sadakichi Takano and his second wife, Mineko. He was the family’s seventh child, and when asked for a name for this new son, Mister Takano, at the time 56 years of age, decided to name him after his age. In Japanese, the name Isoroku means “fifty-six” (I = 5; so = 10; roku = 6). The boy grew up regaled by tales of the battles of the Echigo clan, to which his family belonged, as they fought against the unification of Japan just a few decades earlier. Now, the family was poor, and young Isoroku had to borrow his schoolbooks as there was no money to purchase them.

There was little contact with the outside world, and only one Westerner, an American missionary named Newell, lived in the village. It was from this contact that the future admiral would later gain his interest in Christianity. It was also at this stage that he developed his interest in fishing and the sea in general.

By the age of 15, Isoroku decided to apply to the Japanese Naval Academy and entered the naval academy in 1901. The four-year course demanded that the cadets neither drink, smoke, eat sweets, or go out with girls.

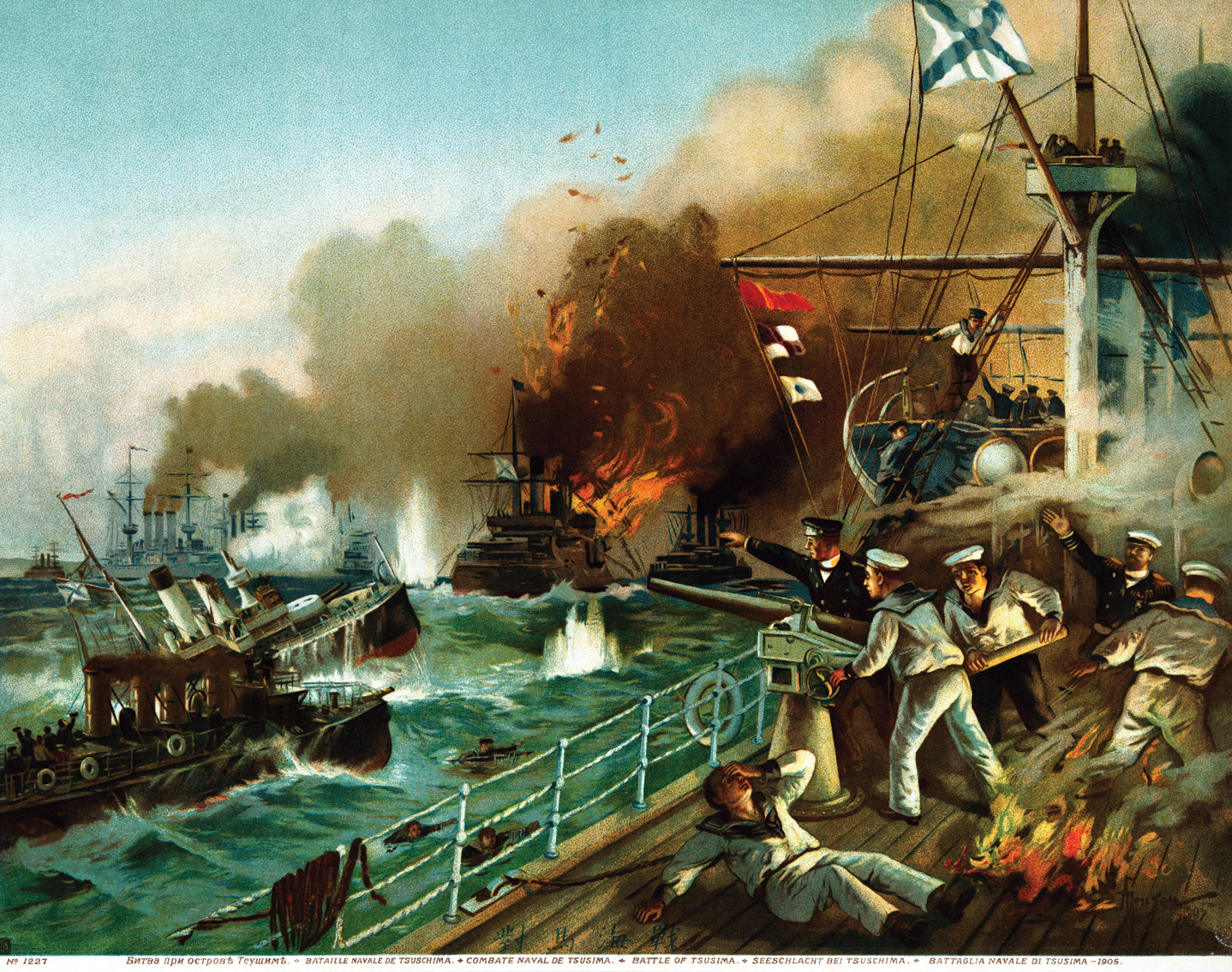

Isoroku Nakano graduated seventh in his class from Etajima in 1904. His timing was excellent, for Japan was about to go to war with Russia. Ensign Nakano was posted to the cruiser Nisshin, part of Admiral Heihachiro Togo’s battle fleet, which was to face the

Russian Baltic Fleet in the epic Battle of Tsushima. In less than an hour, the Russians were defeated, and the Japanese navy had a new laurel to add to its flags.

Ensign Nakano distinguished himself in this, his first battle. He wrote to his family afterward, “When the shells began to fly above me I found that I was not afraid. The ship was damaged by shells and many were killed. At 6:15 in the evening a shell hit the Nisshin and knocked me unconscious. When I recovered I found that I was wounded in the right leg and two fingers of my left hand were missing. But the Russian ships were completely defeated, and many wounded and dead were floating on the sea. But when victory was announced at 2 a.m., even the wounded cheered.”

After two months recovering in the hospital, Ensign Takano went home, where he spent several more months resting. During this period, he studied many Western books, including the Bible. When criticized for this, he would reply that Western books had a great deal to teach Japan.

Training cruises to Korea and China filled the next few years. At age 26, he visited America, then Australia. In 1913, his father, Sadakichi, died at the age of 85 and, according to Japanese custom, the 30-year-old naval officer accepted an invitation to be adopted by a locally prominent family named Yamamoto (Base of the Mountain). The Yamamoto clan was wealthy and could trace its origins back to local clan chieftains, one of whom had been a general during the Shogun wars.

Newly promoted Lieutenant Commander Yamamoto was now in his thirties but unmarried, unusual for a Japanese officer at that age. Eventually he married the daughter of a hometown dairy farmer, Reiko Mihashi, on August 31, 1918, at the Navy Club in Shiba, Tokyo. Despite four children over the next 14 years, the couple seemed estranged from the early days. Shortly after his marriage, Commander Yamamoto was ordered to attend a two-year course at Harvard University. Wives did not accompany their husbands on these assignments.

After a brief visit to Washington, D.C., he went on to Boston where, in addition to his studies, he became an avid poker player. During one vacation, he hitchhiked to Mexico, where he toured the oil fields there. Before he left after his two-year course, he was so knowledgeable about oil that several American oil companies offered him a job. He also studied reports from World War I, then just ending, about airplanes and their use in war. With this began his first beliefs that the airplane would replace the battleship in future naval wars.

In 1923, at the age of 39, came promotion to captain and Yamamoto’s first major assignment, as executive officer of the air-training school at Kasumigaura. This school, copied from the Royal Air Force, taught flying to young recruits. Captain Yamamoto studied flying at night and performed his executive-officer duties during the day. Yamamoto participated in all the sports events at the school and took part in the pilots’ group parties, although he did not drink. He remarked, “I have not drunk since I was commissioned. I found that I was not strong in the head and made a fool of myself, so I stopped.” While at the school, Captain Yamamoto insisted that every pilot be trained in night flying, then unheard of in aviation circles.

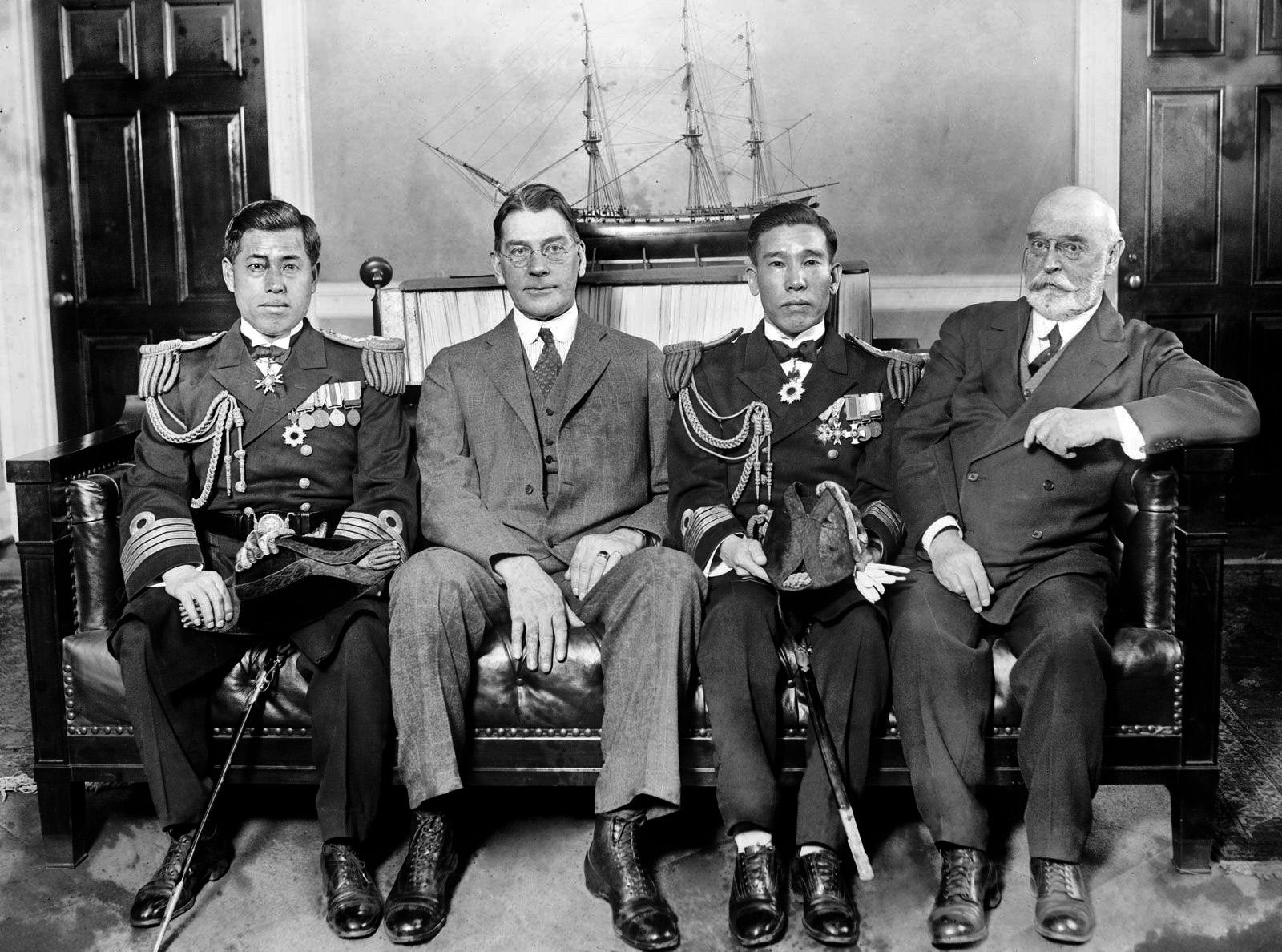

Captain Yamamoto was again posted to the United States from 1925 to 1927. He was naval attaché at the Japanese embassy in Washington, D.C. His job was to learn everything he could about the policies, ship building, and defense programs of the United States Navy.

Yamamoto’s excellent command of English got him assigned as a representative to the London Naval Conference of 1930, where he prevailed on equality in light cruisers and submarines with the other world powers. Command of the First Air Fleet followed, and once again Captain Yamamoto stepped up training. When some of his pilots complained that the training for carrier landings was too difficult, he remarked to them, “The Japanese fleet lags a long way behind the West …. There is very little time to attain their level. That is why I regard death in training the same as a hero’s death in action. The Japanese spirit should not fear death.”

Promotion to rear admiral and assignment to the Imperial Navy’s technical branch followed in 1931. Again, Yamamoto pushed the development of aircraft, particularly fighters and torpedo planes. One result of this pressure was the development of the famous Mitsubishi Zero fighter plane of World War II. In 1934, now-Vice Admiral Yamamoto was selected as the chief delegate for Japan at the new London Naval Conference. Already known for criticizing the earlier conference’s limits on Japan, he was questioned about the speeches of General William “Billy” Mitchell, who had claimed that the United States needed to develop aircraft for the coming war with Japan.

Admiral Yamamoto replied to the reporters, “I do not look upon the relations between the United States and Japan from the same angle as General Mitchell. I have never thought of America as a potential enemy, and the naval plans of Japan have never included the possibility of an American-Japanese war.”

Upon his return to Japan, Yamamoto found that the Imperial Japanese Navy was building warships at an increasing rate. Now Vice Minister of that navy, he opposed the building of more and larger battleships. He told subordinates, “These ships are like elaborate religious scrolls which old people hang up in their homes. They are of no proved worth. They are purely a matter of faith—not reality.” Instead, he demanded that the navy build more aircraft carriers, which eventually they did, launching the new Shokaku and Zuikaku, the biggest and fastest carriers Japan had yet produced.

Vice Admiral Yamamoto was also a leading proponent of avoiding war with the United States. In fact, many of the higher-ranking officers of the Imperial Japanese Navy were against a war with the United States. They believed that their navy was too weak to defeat the American navy and would be for some time. But Japan, led by the Imperial Japanese Army, was already on a collision course with America.

Next, in 1940, came the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, an agreement strongly opposed by Admiral Yamamoto and many naval officers. But they were overridden by the much-more politically powerful Imperial Japanese Army. Admiral Yamamoto now began to regret recently accepting the job of Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial Japanese Combined Fleet. To avoid assassination, a tactic of the extremist Japanese political and military cliques, he remained aboard his flagship, the cruiser Nagato, nearly constantly.

The Prime Minister at this time, Prince Fumimaro Konoye, called Admiral Yamamoto to his office and asked bluntly what chance Japan had of victory in a war with the United States. Admiral Yamamoto replied, “I can raise havoc with them for one year or at most 18 months. After that I can give no one any guarantees.” Based on Yamamoto’s statement, Prince Konoye tried to avert a war with the United States, but things had already gone too far. Soon he was replaced by an army officer, General Hideki Tojo.

Despite the repeated warnings by Admiral Yamamoto, the nation drifted toward war. Once again, this time to a group of senior admirals, he reiterated, “If it is necessary to fight, in the first six months to a year of war against the United States and England I will run wild. I will show you an uninterrupted succession of victories. But I must also tell you that if the war be prolonged for two or three years I have no confidence in our ultimate victory.”

Realizing that he was facing an inevitable conflict, he turned his attention to at least giving Japan a fighting chance. He knew that Japan’s best, indeed only, chance lay in disabling the American fleet at the opening moments of such a war. And so, he began the planning for what was to become America’s “Day of Infamy.” It was then that he gave a speech at his former Middle School in Nagaoka in which he said, “Most people think Americans love luxury and that their culture is shallow and meaningless. It is a mistake to regard the Americans as luxury-loving and weak. I can tell you Americans are full of the spirit of justice, fight and adventure. Also their thinking is very advanced and scientific. Lindbergh’s solo crossing of the Atlantic is the sort of valiant act which is normal for them. That is typically American adventure based on science. Do not forget American industry is much more developed that ours—and unlike us they have all the oil they want. Japan cannot beat America. Therefore she should not fight America.”

Admiral Yamamoto began planning the Pearl Harbor attack around May 1940, when during annual maneuvers he saw how warships at sea could dodge torpedo attacks, even from the practiced and experienced Japanese pilots. When discussing this with his staff, who felt that such attacks would not achieve decisive results, he remarked, “An even more crushing blow could be struck against an unsuspecting enemy force by mass torpedo attack.” Admiral Yamamoto was thinking of the American Pacific Fleet and how to best disable it. He was also implementing his long-held beliefs that air power would be the decisive element in the coming war. But for a while, nothing came of this thought.

In November 1940, the British Royal Navy attacked the Italian Navy while it was in port at Taranto. A small group of carrier-borne aircraft struck suddenly and sank or damaged three Italian battleships as they lay docked. This caught the attention of Admiral Yamamoto, who immediately called for detailed reports from the Japanese naval attachés in Rome and London. Clearly, if the British could do this, so could the Imperial Japanese Navy. Then he checked on the new base of the U. S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The water depth, a key element in any torpedo attack, was nearly the same as that at Taranto. If Japanese torpedoes were modified to run at shallow depths and the attack was sudden, there was every reason to expect success.

Admiral Yamamoto was not the only one who understood the significance of the Taranto attack. American naval officers also understood what possibilities now existed for an attack on the enemy’s harbors. Rear Admiral Patrick L. N. Bellinger, then commanding patrol bombers at Pearl Harbor, and Major General Frederick L. Martin, commanding Army Air Forces in Hawaii, wrote a joint report in which they concluded that Japan could declare war and immediately launch a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, that this attack would be directed at both American warships at anchor and their supporting installations, and that the most likely form of attack would be by carrier-borne aircraft from undiscovered fleet units. Finally, they concluded that such an attack was best launched at dawn. It was almost as if they were reading Admiral Yamamoto’s mind. But this report was ignored.

It was not until after the November 1940 Taranto attack that Admiral Yamamoto brought up Pearl Harbor. In an impromptu staff meeting, he suddenly remarked, “An air attack on Pearl Harbor might be possible now, especially as our air training has turned out so successfully.” He immediately ordered his staff, under the strictest secrecy, to begin to study such an operation and come up with all possible problems, concerns, and issues. One of Japan’s premier flying officers, Rear Admiral Takijiro Ohnishi, was given the task of creating a plan for aircraft to attack Pearl Harbor from carriers at sea. Later, Admiral Ohnishi would be the leading proponent of the desperate Kamikaze tactic.

Six of Japan’s aircraft carriers were selected to participate in the attack. Admiral Yamamoto, the inveterate gambler, was again gambling, for if these carriers were lost, Japan would be nearly defenseless against an American naval advance upon her shores. The most competent and best-trained flyers were selected for the attack force. Secrecy was paramount. Only a handful of senior officers knew what they were training for, or where it would take place. Reports were gathered from naval attachés in the United States, Hawaii, and the Philippines.

There were some scares, however. In early 1941, a Japanese interpreter assigned to the Peruvian embassy drank too much and suddenly blurted out, “The American fleet will disappear!” Peru’s Minister to Japan began to ask questions and eventually submitted a report to the American Ambassador to Japan, Joseph C. Grew, that he suspected an attack on Pearl Harbor was being planned. But, fortunately for the Japanese, the report was discounted by the Division of Naval Intelligence.

By the end of April 1941, the final plans were being discussed. There remained two problems. First, making the necessary adjustments to the torpedoes to run in the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor. Second, how best to get close enough to Hawaii to launch a surprise attack on the American bases there. Staff officers were giving the plan at best a 60 percent chance of success. Most gave it less than a 40 percent chance of success. But Admiral Yamamoto, after carefully studying the plan, believed it stood a good chance of success. Still opposed to the war, he also believed that since it seemed unavoidable, it was his duty to give Japan the best possible chance of success.

In August 1941 the Imperial Navy planners established their planning headquarters in Tokyo, where they conducted numerous war games to test their plan. These sessions brought out significant opposition to Admiral Yamamoto’s plans for Pearl Harbor. Most senior navy men believed it too risky. The Naval General Staff was completely opposed to it. Even Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who would command the attack on Pearl Harbor, was against the idea. He believed that the carriers were too vulnerable to a few bomb hits and that losses would be significant. He would be proven correct later at Midway.

Admiral Yamamoto stood by his plan. He believed that Japan’s only chance was to cripple the American fleet in the opening hours of the war. To wait for them to come to Japan would be the death of the Imperial Japanese Navy. If the U. S. fleet were crippled at Pearl Harbor it would give Japan the opportunity to take Malaya, the Philippines, and Java and the East Indies, with their oil.

The attack on Pearl Harbor has been described as either a great strategic success or a blunder that would cost Japan dearly in the coming years. It did cripple the U. S. fleet for many months, but it did not do much damage to the critical aircraft carriers on which Admiral Yamamoto knew the rest of the war depended. But as he predicted, for the next six months the Imperial Japanese Navy “ran wild” in the western Pacific, conquering island after island, gaining the much-desired oil reserves and other war materiel they would need to bring this war to a satisfactory conclusion. The American Asiatic Fleet was eliminated, the Philippines seized, and Australia threatened.

The Pearl Harbor success also gave Admiral Yamamoto unusual power within the navy. In theory, he reported to the Naval General Staff, but after Pearl Harbor it was he and his staff who made all the decisions about Japan’s naval war. But this brought other problems. Although he never wavered from his pre-war thoughts about a victory, his staff—indeed, most of the Japanese military leaders at this time—began to suffer from “Victory Disease,” a notion of true invincibility. With this, they planned operation after operation under the assumption that they could not be stopped. And for months, they were correct.

Early in the war a press release by Japanese radio purported to detail a message from Admiral Yamamoto, now a national hero, which said in part, “Any time war breaks out between Japan and the United States I shall not be content to capture Guam and the Philippines and to occupy Hawaii and San Francisco. I am looking forward to dictating peace to the United States at the White House in Washington.”

Although widely believed, even today, to be Admiral Yamamoto’s words, they in fact were written as part of a much longer letter to an acquaintance and taken out of context by Army propagandists. This letter, written before the war on January 24, 1941, by the admiral actually said, “Should hostilities break out between Japan and the United States it is not enough that we take Guam and the Philippines or even Hawaii and San Francisco. We would have to march into Washington and sign the treaty in the White House. I wonder if our politicians who speak so lightly of a Japanese-American war have confidence as to the outcome and are prepared to make the necessary sacrifices?”

Admiral Yamamoto was still undecided about where to go next when the issue was resolved for him. All along, he had been seeking what the Japanese called a “decisive battle” in which the striking power of the American fleet was destroyed. The Pearl Harbor attack, which had missed the aircraft carriers and American oil reserves in Hawaii, had not accomplished this, despite its otherwise successful results. Seeking to lure the enemy into such a battle, Admiral Yamamoto chose for his target the lonely Pacific outpost of Midway atoll, where he would strike and hope that the American fleet would respond. Even as his staff prepared the Midway plan, American bombers appeared over Tokyo. This was a severe blow to Admiral Yamamoto, who had always believed that it was vital that no harm come to the Japanese Emperor. Then an American task force under Admiral William F. Halsey attacked Marcus Island, barely 1,000 miles from Tokyo. The threat was clear.

Admiral Yamamoto sent his own carriers looking for the Americans who had dared enter Japanese home waters. Fleet carriers were sent to the Solomons, and in early May came the Battle of the Coral Sea. Generally considered a draw, the battle drew Admiral Yamamoto’s attention to the lowered skill of many of his pilots. Two fleet carriers, originally destined to participate in the Midway operation, needed repairs and had to be dropped from that plan. Disappointed with the results of his aviators’ bombing and torpedo efforts, he began to realize that time was running out. To offset this, he needed another chance to cripple the American fleet.

Once again, over the objections of many senior naval staff members, he went ahead with his Midway plan. But the Americans knew they were coming, and the Combined Fleet was smashed, with a loss of four fleet carriers. Many of the most experienced aviators were lost as well. Sailing some 300 miles behind his attack force, Admiral Yamamoto took no part in the actual battle until the Japanese carriers began to burn, one after another. Determined to win, he kept up the battle even after his scouts reported five American carriers (there were just two) participating.

Disgusted with Admiral Nagumo’s performance, he relieved him of his command and replaced him with Admiral Nobutake Kondo, who went racing toward the embattled Japanese fleet. Then Admiral Yamamoto decided on a night battle, in which the Japanese excelled, with his large warships, including the Yamato. But that did not work out either, and soon he was ordering a withdrawal. So severe was this defeat that for months it was hidden from the Japanese public.

Admiral Yamamoto was one of the earliest proponents of a withdrawal from Guadalcanal. The steady attrition of the Imperial Japanese Navy while trying to support and supply the army had become critical. But once again, the Army prevailed and insisted that these futile attempts continue. Only months after Admiral Yamamoto wanted to withdraw did the Army finally face the inevitable and evacuate Japanese troops from that deadly island. Even in that withdrawal, skillfully conducted by the navy, additional ships, aircraft, and aircrew were lost.

This defeat caused Admiral Yamamoto to become concerned about the morale of his men on the fighting front, and he decided upon a tour of the frontline bases in the Solomons to do what he could to maintain that morale. Not all his staff agreed with this trip, but the admiral insisted, and it was scheduled. Unfortunately, his schedule was signaled to these frontline bases, and those signals were being read by American intelligence.

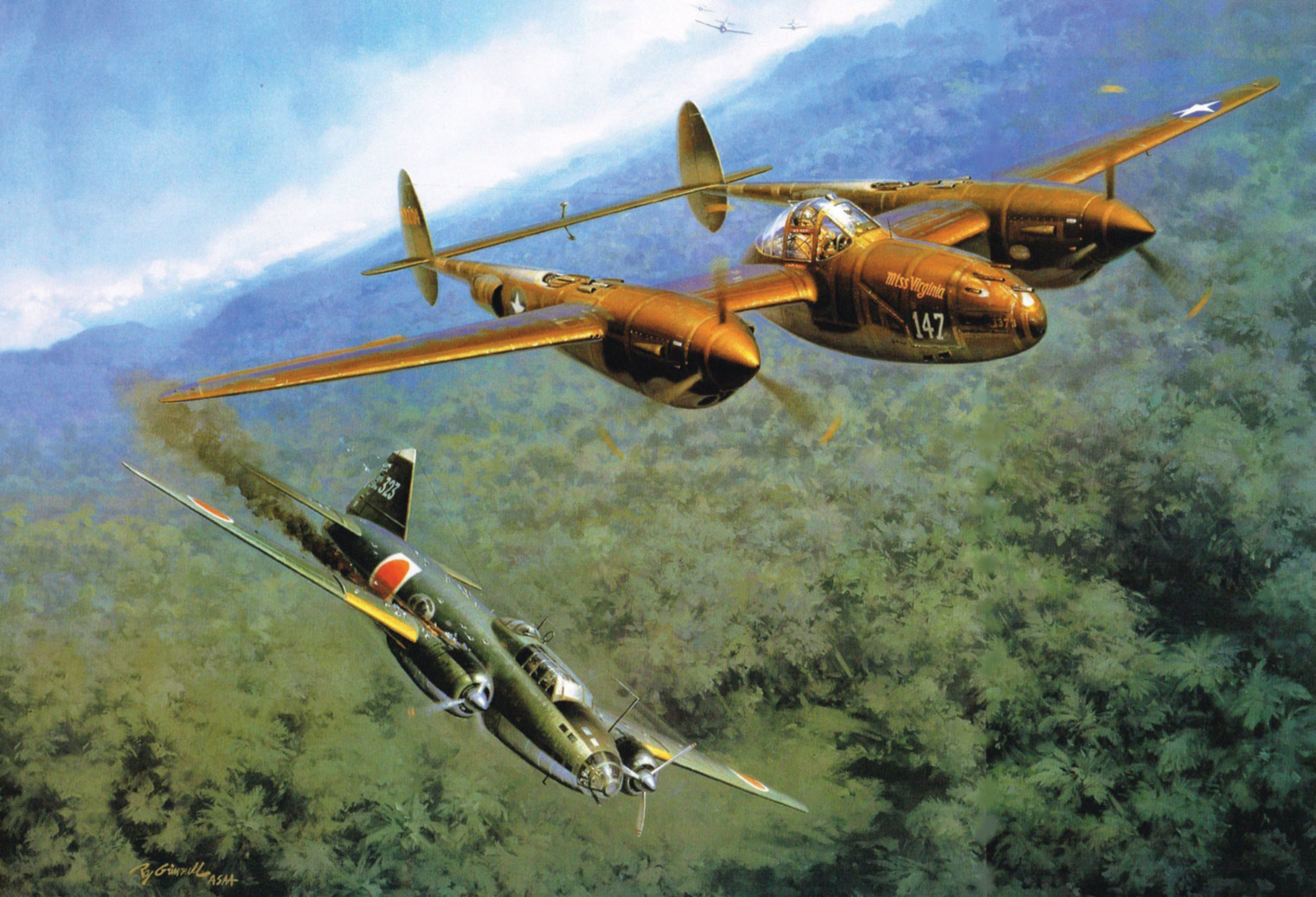

On April 18, 1943, Admiral Yamamoto and his staff boarded two Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers and went on this long-planned inspection trip of his frontline installations in the Solomons. Once again, American code breakers had learned of his plans, and a decision had been taken to kill the man most feared by Americans. The Japanese bombers and their fighter escort planes flew along the west coast of the island of Bougainville. They were suddenly attacked by a group of American Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter aircraft from Guadalcanal. Both bombers were shot down. According to a survivor, one plane landed in the jungle and the other in the water.

Search parties were immediately dispatched, and two days later the aircraft in the jungle was located. Only one occupant had been thrown clear, still strapped into his seat. “Dead bodies were lying about the wreckage. Among them was a high-ranking officer. He sat as though abstracted, still strapped into his seat, amidst the trees. He had medal ribbons on his chest and wore white gloves. His left hand grasped his sword, and his right hand rested lightly on it. His head lolled forward as though he was sunk in thought, but he was dead. This officer was the only one who had been thrown out of the plane in his seat.” Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto had died as he had lived, a naval officer to the end.

Nathan N. Prefer is the author of several books and articles on World War II. His latest book is titled Leyte 1944, The Soldier’s Battle. He received his Ph.D. in Military History from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps Reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.

It is interesting that the attack on Pearl Harbor was well served by the Naval intelligence and Washington Army offices failure to emphasize the coming possibility of danger so that some sort of proper defense could be organized. As it happened, the Japanese, Yamamoto included, were over confident at Midway when Lt. Cdr. Rachford and his signals interception group were listened to and the Navy successfully ambushed the Japanese. Even so, to quote Wellington, “it was a near run thing.”