By Patricia Overman

The sacrifices made by American men and women in uniform during World War WII are legion. The contribution made by the workforce of our nation’s industries, exemplified by the image of “Rosie the Riveter” with riveting gun in hand, is also well known by most Americans. What are less familiar are the contributions made by U.S. colleges and universities both in preparation for and during the war. This is the story of one of the150 colleges that answered the call.

Even before the United States was officially involved in World War II, the Army Air Force (AAF) Aviation Cadet Training Program was running at maximum capacity. After the attack on Pearl Harbor it was clear that even more pilots would be needed. Men were signing up in droves to enlist in the Army, Navy and Marine Corps, and, with the lowering of the draft age to 18, all of the services were increasing their size at an unprecedented rate.

The problem facing the AAF, however, was not just a need for manpower. The AAF needed qualified manpower—men who had the aptitude to successfully pass all three phases of aviation cadet training. In early 1942 two changes were made by the AAF to ensure that a sufficient supply of candidates would continue to be available for the Aviation Cadet Training Program.

First, the two-year college requirement was dropped because the number of men with two years of college had been depleted. Second, the Aviation Air Forces Examination was redesigned to test for aptitude instead of knowledge. These two changes resulted in a tremendous increase in the pool of qualified candidates.

To keep these candidates from being drafted by other branches of the military while they were waiting to be called to service, a third change had been implemented: the formation of the Air Corps Enlisted Reserve (ACER). This program allowed the AAF to hold men eligible for the Aviation Cadet Training Program in reserve until they could start their training.

While ACER solved one problem, it created another. More men than anticipated were passing the Aviation Cadet Examination, and many of these men were left in limbo as it was taking as long as six months before they could be placed in training.

At the time, the AAF’s training facilities had room for 10,000 men per month, but they were gaining 13,000 men per month, resulting in an increase every month of 3,000 men either waiting at home or continuing in their civilian jobs. Not only were the men complaining about not getting called to duty, this perceived hording of manpower did not please either the Selective Service Board or the War Manpower Commission. As a solution to this predicament, General Henry H. (“Hap”) Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces, proposed the College Training Program.

It took 60 weeks to transform a cadet into a pilot. However, only 28 percent were completing the program. One reason was failure to keep up with the academic and critical thinking demands. General Arnold believed that while men were waiting for placement in the Aviation Cadet Training Program, continuing education would help reduce that failure rate. Potential cadets would no longer just wait for available placement in the aviation cadet training program but would be called to active duty and assigned to a College Training Detachment.

The goal of the college program was to graduate these men with the same level of knowledge; an equal and high standard of education to increase retention during the next three rigorous phases of the cadet’s aviation training.

This purpose, stated in an Army Air Force memorandum of the day, was mandated to the colleges: “The College Training Program contemplates the assignment of students to college training for a period of five months, designed to prepare the student educationally to understand the basic principles of mechanics, physics, mathematics and political geography, combined with physical and military training considered essential to operate and navigate modern high-powered aircraft in combat.

“The curriculum varies both in scope and in purpose from the normal curriculum of educational institutions, and in its treatment the purpose should be clearly kept in mind by all concerned in order that the time of the students and their efforts will not be wasted in work which does not contribute to the purposeful intent, that of educationally equipping each student to understand the basic principles behind the operation and navigation of the weapon as the ‘military airplane.’ Without an understanding of the principles outlined in the curriculum, these students become a hazard to scarce and expensive equipment, as well as to the lives of highly trained personnel.”

All of this was to be accomplished in a maximum of five months. The 150 colleges accepting the cadets would need to prepare the cadets for this challenge, and those colleges would be administering the Army’s version of “education on steroids.”

The Army used several very specific criteria for selecting a college for their Air Crew Cadets. Beloit College, a small (enrollment about 1,200) school in Beloit, Wisconsin, was one of the qualifying colleges for this program because it met five of the most important criteria: first, an excellent faculty and curriculum; second, dormitories; third, a mess hall (cafeteria); fourth, athletic facilities; and fifth, close proximity to an airport, Machesney, just across the state line in Rockford, Illinois.

Beloit College, founded in 1847, was also a good candidate because it had a history with the government and America’s defense: in World War I the college was used as a training station. In addition, the college had already been proactive in the current war effort when, in 1939, the college’s Board of Trustees voted to participate in the Civil Aeronautics Program by providing a ground school to prepare college students for further flight training.

A faculty committee was appointed by College President Irving Maurer to discuss all national-defense problems that related to faculty and students and to explore ways in which the college could be useful to the government’s defense program. In early 1941 Professor Philip Whitehead, chairman of the faculty group, sent letters to the Wisconsin Militia, the XI Corps Army Area located in Chicago at Camp Grant; the president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; and the president of the United States offering their facilities and the services of Beloit College to the National Defense Program.

As the Beloit College faculty began working with the government in support of national defense, a majority of the student body was going in the opposite direction. They considered themselves “isolationists” and not only voted overwhelmingly to stay out of the war effort but to offer Beloit College as a place where men could go to avoid enlistment under the Deferred Enlistment Program.

An article in the student newspaper demonstrated this point of view:

“This brings to mind the question of military training in the smaller colleges which are without the jurisdiction of state legislatures. Shall schools such as Beloit maintain units of the Reserve Officers Training Corps? We think not.

“Until a more vital need than the existing is proven to us, we recommend no change on our campus. Here remains one sanctuary for civilian life in all its carefree glory in a world surrounded by conscription and preparedness. We would far rather suffer the sight of worn-out saddle shoes and corduroy shirts than have the nattiest of uniforms paraded before us every day of the year.”

After the events of December 7, 1941, the student body did an about-face. There was even a place on campus to enlist, and the men of Beloit stood in line to sign up.

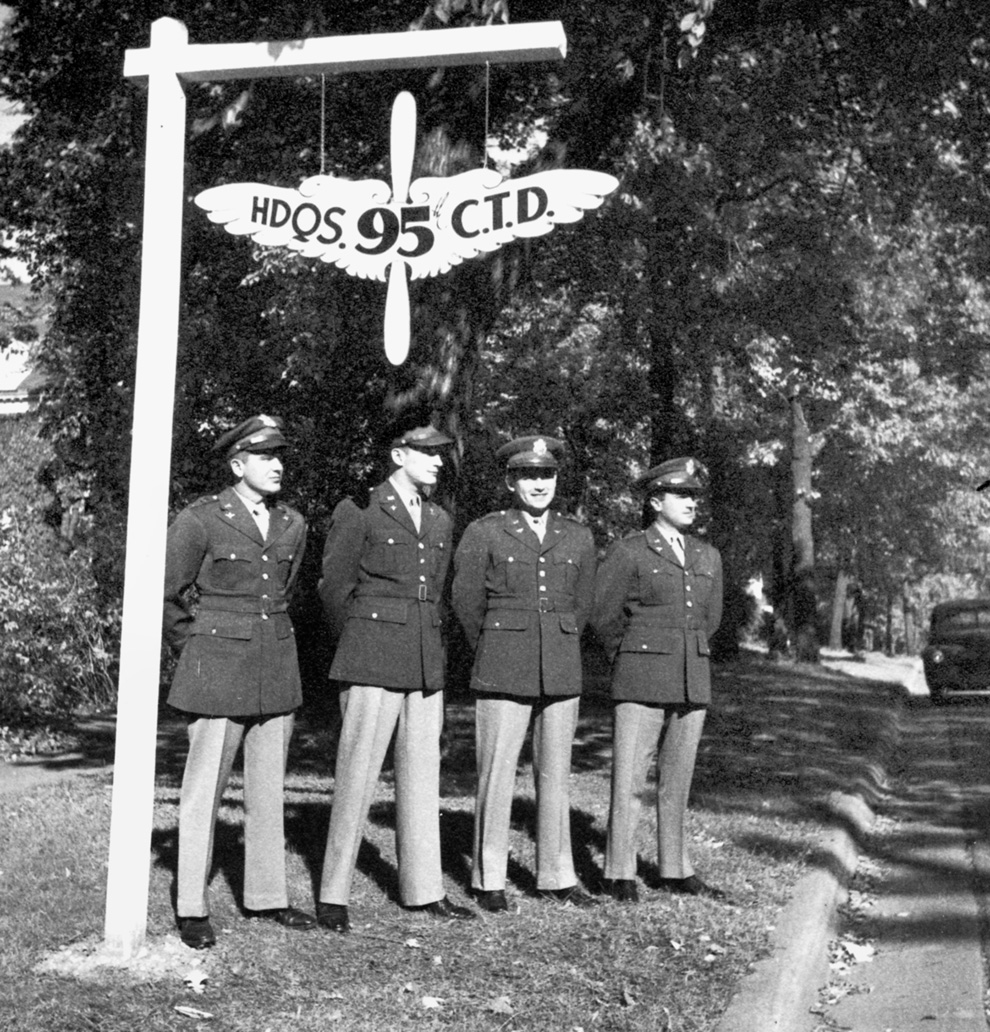

On February 20, 1943, Beloit opened its doors to the 95th College Training Detachment (CTD)––the first detachment of 150 Army Aircrew Cadets, soon to be 300 strong. These were the men who would become the pilots, bombardiers, and navigators who would crew the bombers, fighters, and troop carriers––the men who would put their lives on the line for America’s freedom and for their comrades. Many would make the ultimate sacrifice.

The Army had to make physical changes to the college to accommodate the cadets. The estimated startup cost was $6,111 and included building alterations, equipment additions, and activating an infirmary. Dorms were remodeled to handle bunk beds, extra study desks (for supervised study in individual rooms), lockers, dressers, and bookshelves. Gym classes for cadets were moved to the Walter Strong Memorial Stadium to accommodate the enhanced obstacles needed to meet Army specification (the wall and pits). Physics classes had to be expanded. Fifty percent of Beloit’s facilities were used by the 95th CTD.

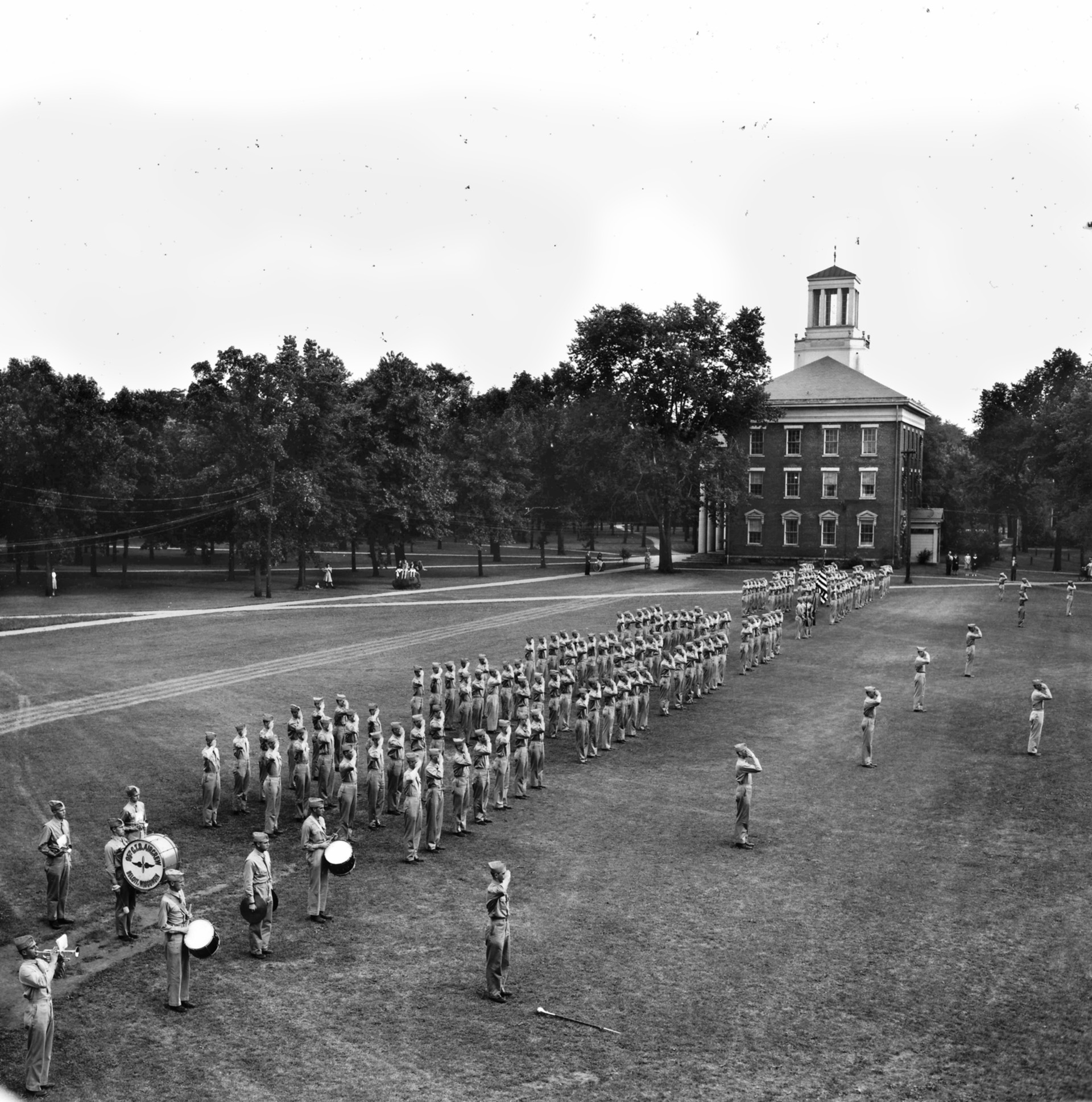

The total strength of the 95th CTD was 300. This number was divided into five squadrons of 60 cadets each. The squadrons were further divided into two flights of 30 cadets. Which flight a cadet was placed in was determined by his academic test score. Cadets who scored the highest were in the same flight and graduated out of the CTD in two months. Those with the next lower test scores were in a flight that graduated after three months, and so on, with those having the lowest passing scores remaining in the CTD for five months. The cadet’s official title was Aircrew Student (though they were still referred to as “cadets”) and they were addressed as “Mister.”

When the cadets arrived each month in groups of 60, they were first addressed by the president of Beloit College, Bradley Tyrrell: “We hope you will feel that Beloit is your school, and thus can become ‘Alma Mater’ to you as she has to thousands of other students over the years. All these sons and daughters of Beloit will be watching your progress here with loyal and friendly interest—your future achievements with pride and gratitude.”

They were then addressed by their commanding officer, Captain Charles Manning: “As you enter the College training phase of your aircrew training, your status in the Army has changed from a “GI” soldier to a full-fledged Aviation Student and potential flying officer…. It will be a tough grind for many of you and some of you will fail to make the grade…. The high standards of discipline, honor, leadership, and military bearing have characterized the men of the Army Air Forces since its beginning.

“I know you are proud of these standards and will keep them constantly before you throughout your Army career. To all of you, on behalf of the officers and non-commissioned officers of the 95th College Training Detachment, I say best of luck and happy landings.”

Sixteen men met the needs of the cadets, from food, to pay, and 280 hours of basic military indoctrination; military etiquette, leadership, Articles of War, hygiene and sanitation, infantry drills, ceremonies, inspection, and even guard duty (The men guarded their own dorms, though some wondered just what threat they were guarding against. To them the greater threat was to the women’s dorms.) In addition to the program’s commanding officer, Captain Manning, commandant for students was Lieutenant William Manning (no relation) and later 2nd Lt. Marshall Sipkins. The detachment adjutant was 2nd Lt. John Dewland and the tactical officer was 2nd Lt. William G. Anketell.

Noncommissioned officers were in charge of military tactics and drills. From Sergeant Jack Butler and Sergeant Joe Oleszycki the cadets learned the art of square corners on the parade ground. Close-order drills were conducted during inclement weather on the side streets bordering the college. The residents watched their drills from the comfort of their yards.

Army personnel overseeing the program set forth requirements within the curriculum. Since these men belonged to the military 24/7, class time could be increased, thereby allowing more instruction in the areas needed most for the war effort. As an example, physics was increased by two hours a week, focusing on mechanics, heat, electricity, and light.

Because Beloit was a liberal arts college, art was an important component of the curriculum. The Army embraced this concept wholeheartedly and designed their curriculum around the study of camouflage.

A day’s schedule had the cadets up at 6 every morning and starting class at 8. Every evening began with Retreat, then several hours of study, some of which was supervised, and ended with uniform preparation for the next day. On Saturday, after morning classes, a two-hour inspection was held. On Sunday the cadets attended church.

With the exception of church, the cadets had “open post” late Saturday afternoon through Sunday. Cadets in their last two weeks prior to graduation attended flight training on Saturday afternoon as well as during the week.

In the early stages of the program the faculty determined that the cadets were not keeping up with the rigid demands of the AAF. Upon successful completion of the program, the cadets from Beloit College were transferred for their Aviation Cadet Training Program to the Army Air Forces Western Flying Training Center (AAFWFTC) at Santa Ana, California.

Therefore, there was constructive and open communication between the faculty and headquarters personnel at Santa Ana. On June 19, 1943, after the graduation of one cadet Squadron, Ivan M. Stone from the Department of Geography sent a letter to Major S. Joseph De Brum acknowledging the “wisdom” of the Army to include geography into the curriculum, as many of the men were lacking in this area. Mr. Stone did, however, go on to suggest that the men were in need of more sleep:

“The Army should be complimented in allowing the various colleges to substantially prepare their outline of the instruction in Geography…. The materials supplied to us were adequate, and I have no criticism from that quarter. All together, the men in the course were bothered and diverted from their primary task of learning by too many diversions of sundry sorts.

“There was regularly evidence that the men had not received enough sleep to permit them to get the most out of the class hour—they were often present in flesh only, and had to fight to stay awake. Obviously, this constitutes a waste of time so far as progress in the academic subject is concerned.”

Captain Charles Manning, the commanding officer of the detachment, commented on their rigorous training: “There is little in the life of the aviation cadet to bring back nostalgic memories of the informal days of ‘Joe College.’ The life is rough from early morning until late at night, and always there is the strict military discipline making soldiers from all….”

Even with all these demands on the cadets, only 3.8 percent failed to go on to the AAFWFTC. Some asked to leave and others who could not meet the standards were immediately transferred; they went on to ground training or to other Army organizations.

The largest impact to the college was on the faculty’s time and responsibilities. Increased class time also meant increased faculty responsibility. The faculty absorbed and implemented all the required changes. At least 75 percent of the faculty took on extra work, giving freely of their time and knowledge to instruct the cadets. The faculty did this without complaint, devoting much of their personal time.

The extra workload also affected the flexibility for civilian classes as was revealed in regular announcements: “The athletic department now carrying a tremendously increased load, will find it impossible to reschedule classes for afternoon times as was done last fall.”

Faculty teaching math, geography, physics, and athletics were now teaching specific information required by the AAFWFTC. Among these were map reading, including aerial; supplementary mathematical material; quantitative and qualitative problem solving in physics, etc.

The continuing communication between Santa Ana headquarters and Beloit College included informing the faculty how the graduating cadets were testing at Santa Ana. The scores were given back to the Beloit College faculty with the request to improve the training in the areas where cadets were consistently receiving low scores.

As an example, the Army requested that greater emphasis in the geography classes be placed on: “1. Latitude and Longitude; understanding world grid and location of points by geographic co-ordinates. 2. Measurement of distance; nautical miles, statute miles, and kilometers as well as conversions. 3. Map Projections; types, properties and their uses. 4. Conventional Map Signs and Symbols.”

It was recommended that a passing grade of 90 percent be required of all cadets in these particular phases of training (a passing grade for the Army was usually 70 percent). These constant evaluations were taken in stride by the faculty and were applied to the best of their ability.

The cadets outnumbered the noncadet male population at Beloit, but those men on campus who were not serving actively were all slated in some way for the war effort. Some were Marine and Navy Reservists awaiting their call to active duty. Others were deferred because their educational major was essential to the war effort. The cadets, however, were the only men under the direct control of the military. The cadets were required to march, singing or chanting to keep the cadence, from class to class.

The intertwining of military indoctrination and education throughout the cadets’ day proved to be a very successful method of implementing military training and preparation for Army discipline. This was enforced by unexpected inspections that occurred between classes and was observed by civilian students. The civilian students would stop to watch as the cadets, never taking their eyes from the back of the head of the cadet in front of them, marched by. Cadets, for their part, got very good at using their peripheral vision to evaluate the female population on campus.

The fraternities took turns graciously inviting the cadets to their formal dances where their favorite local band would play. On the cadets’ first dance they were introduced to the female students, one at a time. The women were lined up and a faculty member would begin the introduction to the first women in line and that woman would introduce the cadet to the women next to her and so on down the line. Usually, by the end of the line, the cadet’s name did not sound familiar even to the cadet.

The cadets reciprocated with their formal graduation dances, which occurred once a month. The civilian students especially enjoyed the cadets’ dances for two reasons; the 95th CTD had a dance band that was very good, and the female students were permitted to stay past their curfew to attend the whole evening. This was an occasion when the cadets put aside their military bearing for one night before going to Santa Ana and another step toward war.

In mid-September 1943, “mixers” were added to the social curriculum. Almost all of the civilian students were now women. Twice a month 19 women were chosen to attend a mixer with each flight of cadets.

The cadets also made an impact on the community. The citizens of the City of Beloit suddenly found themselves visiting the college in the evenings. Army experts, who trained the cadets, frequently put on evening exhibitions such as demonstrating Jiu-jitsu or the modern method of self-defense used by the Army. The citizens took special pride when watching the cadets drill or listen to a bugle call when striking the colors.

Today the area that was Machesney Airport is a shopping mall, but from March 1943 to March 1944, Fred A. Machesney, owner of the airport, and his civilian staff took the 95th College Training Detachment Cadets under their wings, literally. With direction from the AAFWFTC, Machesney, Chief Flight Instructor R.S. Day, and nine Civil Aeronautics Authority-qualified instructors gave the cadets their first taste of flying.

This flight training occurred two weeks prior to a cadet’s graduation. For the cadets, this was what it was all about. The cadets were bused to the airport, a little over 20 miles south of Beloit College. Awaiting them were 11 Piper Cub model J-3 trainer airplanes, as well as a new official title, Aviation Student.

They were also now granted $10,000 worth of flying insurance and flight pay, 50 percent of their basic pay, which was $50 a month. Cadets were now making the extravagant amount of $75 a month!

During this training the cadets learned elementary flight maneuvers, landing, and traffic procedure on an airfield 2,800 feet by 2,100 feet. The landing area was an unpaved grassy strip. The airport buildings were remodeled to add a “ready room” where daily ground instruction was held.

All cadets received the necessary air training, which included 10 hours of flying instruction and 10 hours of ground instruction. All flight instruction was headed by Mr. Day, and all classroom and flying instructions were given in a military fashion. Military forms, records, and rules and regulations were all taught by the various instructors. All cadets kept a rating book documenting their progress and deficiencies.

Inspections were conducted by military officers from AAFWFTC and feedback was given at a round table discussion with the flight instructors. The instructors reported that these discussions were a great aid. It was also reported that the relationship between the 95th CTD and the flight instructors “was the best … a benefit to all participants.”

The Army Air Force had no interest in having the cadets fly while attending their CTD but the War Department mandated otherwise. Once mandated, the AAF used this flying time to familiarize the cadet with flying but prohibited the cadet from soloing. Even so, this provided an early opportunity for the AAF to evaluate whether a cadet would make the grade and another opportunity for the cadet to wash out. This was also the point that some cadets decided that flying was not for them and voluntarily left the program.

It’s interesting to note that the AAF, from 1938 through 1945, became the largest single educational organization in existence. The AAF grew from 11 percent to just shy of 33 percent of the Army’s uniformed personnel. Some historians and authors have written that the College Training Program was noneffective and that it was only a place to “park” the cadets until they could be placed at an Air Force Training Center. General Arnold and the men conducting the training at Santa Ana would have disagreed.

Additionally, the CTD was successful by aiding in preflight and primary flight training. “A 1944 study of the program showed that the indoctrination [flight] training contributed to the students’ progress materially in the early stages of primary [flight] training….”

By the end of the program in March 1944, 100,000 men had entered the Aviation Cadet Training Program through the 150 colleges offering the program. During the year the CTD program was operating, 1,100 cadets had come and gone through Beloit College.

Beloit’s willingness to serve the country by opening its doors to the men of the 95th Cadet Training Detachment is, to this day, a historical treasure for Beloit College and a credit to the country they served. Captain Manning’s prediction about nostalgia is doubtful; the young men never forgot the campus they once called home or the faculty who prepared them for a successful aviation career.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments