By Al Hemingway

On April 30, 1975, the American-backed government in Saigon, South Vietnam, fell to the Communists. For those who served in what was then our nation’s longest war, it was a time of sadness, bitterness, and anger. How could the strongest nation in the world be defeated by a third-world country? Who could forget the sight of CH-46 Sea Knights lifting off the roof on the U.S. Embassy, with desperate stowaways clinging to the sides?

Although one can spend countless hours debating such questions, there is no debating that those Americans serving in South Vietnam in those last, harrowing days literally went above and beyond the call of duty to ensure that every individual possible was evacuated to safety on the ships lying offshore.

Although one can spend countless hours debating such questions, there is no debating that those Americans serving in South Vietnam in those last, harrowing days literally went above and beyond the call of duty to ensure that every individual possible was evacuated to safety on the ships lying offshore.

In their new book, Last Men Out: The True Story of America’s Heroic Final Hours in Vietnam (Free Press, New York, 2011, 304 pp., photos, notes, index, $26.00, hardcover), authors Bob Drury and Tom Clavin trace the terrible last hours of the Vietnam conflict, focusing on how a detachment of leathernecks stood their ground until the book was closed on the long, frustrating, ultimately heartbreaking war.

The authors did yeoman’s work in researching new, never-before-seen documents that have recently been declassified. They also conducted interviews with the participants to obtain firsthand accounts of the tragic events that transpired in the closing days of the war.

Major Jim Kean and Master Sergeant Juan Valdez, both with prior service in Vietnam, led the heroic efforts of the Marine detachment during the terrifying 24-hour ordeal immediately prior to the collapse of the Saigon government. The tiny security guard unit could not look for any assistance from the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Most South Vietnamese soldiers already had thrown down their weapons, and fled southward, killing, looting and raping victims in their heedless path.

As darkness fell on the last day of the war, the situation deteriorated rapidly in Saigon as huge crowds of angry South Vietnamese congregated around the American Embassy gates. When the throng realized that the Americans were fleeing the country, they became more and more aggressive in their behavior, screaming and pushing against the fence. Elements of the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines were hastily choppered into the compound to augment the security detachment as the operation continued. One Marine guard, Sergeant Steven Schuller, was bayoneted by an ARVN soldier as he and the others were trying to keep the mobs of civilians and soldiers from gaining entry into the compound.

Marine helicopter pilots played a major role in transporting people to safety. Captain Gerry Berry flew an incredible 18 hours straight and made countless trips ferrying personnel to the vessels anchored just offshore in the South China Sea. With just minutes before the embassy was overrun, the last Marines were aboard a chopper headed to safety. “We never had a doubt that our fellow Marines would return and pick us up,” Kean said later. “They had been doing it all night long.”

Operation Frequent Wind, as it was called, was the largest and most successful helicopter evacuation mission in American military history. The pilots logged more than 1,000 flight hours and flew 682 sorties, 34 of them by Berry alone. In the end, nearly 1,400 American citizens and 5,600 non-Americans were evacuated

Sadly, such heroism does not erase the painful memories of the final moments of the Vietnam War, when the Americans fled the country amid chaos and uncertainty, after the loss of more than 58,000 U.S. service personnel. The war ended, as poet T. S. Eliot once wrote, “Not with a bang but a whimper.”

Unjustly Dishonored: An African American Division in World War I by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2011, 146 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Unjustly Dishonored: An African American Division in World War I by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2011, 146 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The author, a professor emeritus of history at Indiana University, has written this account of the all-black 92nd Division in France in World War I to illustrate that the unit, falsely accused of performing poorly, in fact had fought very well during its time in combat.

Digging through the National Archives and gaining access to a wealth of personal interviews from the division’s officers, Ferrell paints an entirely different picture. The field artillery brigade, led by Brig. Gen. John Sherburne, did a masterful job of supporting the infantry assaults during the Meuse-Argonne campaign that began in September 1918 and lasted until November 11, when the armistice was signed.

Ferrell contends that, with few exceptions, the 92nd suffered from inept officers during the initial stages of the fighting. According to Ferrell, Colonel Fred R. Brown gave “vague directions” to his three battalion commanders; Major John N. Merrill “was an embarrassment to the American Army” because of his strict command style; Major Max A. Elser’s indecisiveness played a key role in their failure; and Major Benjamin F. Norris had little leadership capabilities and passed on command decisions to his subordinate officers.

It certainly appears that it was a recipe for failure. The U.S. Army at that time did not look favorably upon using African Americans in a combat role. The supposedly inadequate performance of the 92nd Division supported their views. Of course, the inferior actions of many white units during the initial stages of the fighting were never mentioned. The 92nd bore the brunt of the criticism.

With the advent of World War II, the new Army realized that, with the proper leadership, any unit, no matter what its ethnic background, could perform well. That was clearly demonstrated when the 92nd gave a good showing during the Italian campaign later in the war.

The Field Campaigns of Alexander the Great by Stephen English, Pen & Sword, South Yorkshire, England, 2011, 246 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

The Field Campaigns of Alexander the Great by Stephen English, Pen & Sword, South Yorkshire, England, 2011, 246 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Arguably the greatest military commander of all time, Alexander the Great never lost a battle. This was an amazing feat considering the fact that his army marched thousands of miles through enemy lands to conquer much of the known world. Keeping his men clothed and fed was a truly Herculean feat for the young commander.

This book traces some of Alexander’s major battles and greatest triumphs. In November 333 bc, the young Macedonian warrior crossed the Dardanelles and defeated the Persians at the Battle of Granicus. The Persian leader, Darius, took personal command of the army and met Alexander at the village of Issus. While the Macedonian infantry attacked the Persian army, keeping them in check, Alexander led his expertly trained cavalry uphill and struck the Persian left flank. During the confusion, he regrouped and gained the momentum by routing Darius’s soldiers.

The ensuing battle was a bloodbath, with reports of bodies stacked so high in the nearby Pinarus River that they blocked the flow of water and the dead soldiers’ blood turned the water crimson.

The book has a wealth of information on the strategies, tactics, topography of the battlefield, and casualties that both sides endured. Maps are included, enabling the reader to follow the movements of the armies and the way in which each commander deployed his men for battle.

Preparing for Victory: Thomas Holcomb and the Making of the Modern Marine Corps, 1936-1943 by David J. Ulbrich, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD, 2011, 285 pp., photos, maps, notes, index, $35.95, hardcover.

Preparing for Victory: Thomas Holcomb and the Making of the Modern Marine Corps, 1936-1943 by David J. Ulbrich, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD, 2011, 285 pp., photos, maps, notes, index, $35.95, hardcover.

Not much has been written about the contributions that Marine Corps commandant Lt. Gen. Thomas Holcomb made during his tenure as the top Marine. The author does a good job in filling this void by outlining the Delaware native’s efforts to increase the size of the Corps during the 1930s, while the country was immersed in the Great Depression. Holcomb’s ensuing hard work to mold the mission of the Corps during World War II made it the premier amphibious fighting force in the world.

Ironically, Holcomb was first rejected by the Marines as being too skinny and unlikely to withstand the harsh treatment that recruits received in their initial training. Through the efforts of his father, a well-known Delaware state legislator, he was finally accepted into the Marines in 1900.

Holcomb was a crack shot and went on to win numerous shooting awards. He was a quick learner who grasped the importance of the issues. His service in China and at the Marine Barracks in Washington, D.C. and his combat duty in France in World War I helped shape his ideas about how to build a new future for the Marine Corps.

Ulbrich’s book highlights Holcolmb’s unique blend of managerial talents, which included combining military and political skills, becoming a publicist to promote the Marines’ image, and a real prophet in the field of amphibious warfare that began with the Guadalcanal campaign and lasted through the assault on Okinawa in April 1945.

Holcomb’s tenure as commandant effectively guided the Marine Corps from a small group of slightly more than 17,000 men just after World War I into to an unthinkable 385,000 men by the time he stepped down in 1943. To many, Holcomb was indeed a visionary, one whose quiet leadership was instrumental in securing a future for the Marine Corps in the American armed forces.

Insurgents, Raiders and Bandits: How Masters of Irregular Warfare Have Shaped Our World by John Arquilla, Ivan R. Dee, Chicago, IL, 2011, 350 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, $27.50, hardcover.

Insurgents, Raiders and Bandits: How Masters of Irregular Warfare Have Shaped Our World by John Arquilla, Ivan R. Dee, Chicago, IL, 2011, 350 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, $27.50, hardcover.

Here is an intriguing book that deals with some of the key individuals who fought as insurgents in a variety of wars throughout the world. People such as Robert Rogers, Nathaniel Greene, Nathan Bedford Forrest, Giuseppe Garibaldi, T.E. Lawrence, and Orde Wingate fought a hit-and-run type of war that totally baffled their opponents and kept them off balance. Arquilla focuses on seeming contradiction when discussing these masters of the insurgent war—how they could sustain a string of defeats and still erode the fighting ability and morale of the enemy.

Greene did this against Lord Charles Cornwallis before the British surrender at Yorktown, Garibaldi did so in Italy, North Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap did so against the French and the Americans in Vietnam, and Boer guerrilla leader Christiaan de Wet confounded the British in South Africa. Although they were beaten on numerous occasions, their steadfastness and willingness to sacrifice prevailed, allowing them to achieve victory when the opposing side tired of the war.

Even Osama bin Laden, who masterminded the September 11 attacks, can be included on the list of master insurgents, although the “jury is still out” on him, the author writes. The author contends that the next conflict will “unfold along irregular lines.” He insists that the past masters of guerrilla warfare should be studied in greater detail to gain a better understanding of their tactics to ensure success.

“In this respect the long debate between the leading conventional and irregular military theorists and practitioners that has flared continually since the 1750s seems finally to be over,” Arquilla writes. “The irregulars have won—a sure and troubling portent of the darkness that lies ahead.”

Great Sioux War Orders of Battle: How the United States Army Waged War on the Northern Plains, 1876-1877 by Paul L. Hedren, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2011, 240 pp., map, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Great Sioux War Orders of Battle: How the United States Army Waged War on the Northern Plains, 1876-1877 by Paul L. Hedren, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2011, 240 pp., map, index, $39.95, hardcover.

A myth has persisted that the U.S. Army was ill prepared to fight Native Americans in the years immediately following the Civil War. Many point to the 7th Cavalry’s humiliating defeat at the Little Big Horn as a prime example of the inept leadership and poor caliber of soldier pitted against the might Sioux warriors and their Cheyenne allies.

The author, however, disputes this claim and asserts that the cavalry and infantry units assigned to the Great Plains to fight the Indian nations were a well-equipped force filled with numerous Civil War veterans, both officers and noncommissioned officers.

Despite the disastrous loss of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s command in June 1876, Hedren says, the Army performed well as a whole and drove the various tribes from their lands, back onto the reservations, or into Canada to seek refuge.

The book is handsomely bound and comes with a richly detailed pull-out map that highlights the forts and different battles that the Army and the various Indian tribes engaged in. It is recommended for those fascinated by this period of American history.

Battle for the City of the Dead: In the Shadow of the Golden Dome, Najaf, August 2004 by Dick Camp, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2011, 312 pp., maps, photos, index, $30.00, hardcover.

Battle for the City of the Dead: In the Shadow of the Golden Dome, Najaf, August 2004 by Dick Camp, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2011, 312 pp., maps, photos, index, $30.00, hardcover.

Retired Marine Colonel Dick Camp has done a superlative job in writing about the exploits of the soldiers and Marines who drove Muqtada al-Sadr’s militant army from its stronghold at Najaf, known as the city of the dead because of its massive cemetery, during the Iraq War. Najaf, with a population of more than a half million people, is located 120 miles south of Baghdad. Al-Sadr, a diehard radical cleric, created an ad hoc force by stirring up anti-American sentiments among the local population.

Despite the intense 120-degree heat, the Americans fought al-Sadr’s Mahdi Militia among the tombstones and mausoleums in the sprawling 12-square-mile Wadi Al-Salam Cemetery. One Marine officer called it “a New Orleans cemetery on steroids.”

Before U.S. troops could defeat the Mahdi Militia, a ceasefire was called, and Al-Sadr fled to Iran. Camp believes this move “just delayed the inevitable” and bolstered the morale of the insurgents, who made their stands in other locales such as Ramadi and Fallujah.

This book is a great testimony to the fighting ability of the average American soldier and Marine who, once again, demonstrated their abilities to operate in unforgiving terrain against a fanatical militant force and soundly defeat it.

Silent Killers: Submarines and Underwater Warfare by James P. Delgado, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2011, 224 pp., illustrations, photos, notes, $24.95, softcover.

Silent Killers: Submarines and Underwater Warfare by James P. Delgado, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2011, 224 pp., illustrations, photos, notes, $24.95, softcover.

Here is another first-rate book from Osprey Publishing. This one traces the earliest pioneers in submarines and underwater warfare. Man has always had a fascination with the concept of submerging in a vessel beneath the waves for a sustained period of time.

Much of the book focuses on the history of the American experience with submarines. From the Confederate vessel CSS Hunley to the boats that prowled the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans in World War II hunting for enemy shipping, to today’s sophisticated nuclear-powered subs, this underwater arsenal has evolved into an effective fighting force.

The book is filled with numerous photographs and drawings to assist the reader as the author explains these intricate machines and the crews that manned them.

Lost Eagles: One Man’s Mission to Find Missing Airmen in Two World Wars by Blaine Pardoe, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2010, 256 pp., notes, index, photos, $32.50, hardcover.

Losing a loved one in a war is a heart-wrenching experience. However, for those families who have someone listed as missing in action, and their remains are never recovered, the pain continues.

Frederick W. Zinn, a World War I veteran, went on a lifelong mission to try and bring closure to these families by attempting to find out what happened to them. Zinn’s story is a remarkable one. Born in Michigan, he traveled to Canada and eventually made his way to England before joining the French Foreign Legion at the outbreak of the conflict in 1914. He was later transferred to the French Air Force and served as a bombardier and gunner. In 1917, when the United States entered the war, he served with the American Army. In all, he survived four years of some of the bloodiest fighting of the war.

The author has done meticulous research in uncovering Zinn’s life and his innovative method for tracking lost airmen from both WWI and WWII. A humble man, Zinn never talked about himself or tried to grab the limelight about his efforts to find missing airmen. Instead, he worked tirelessly behind the scenes, creating a system that is still in use today. His methodology included imprinting all parts of an aircraft with its serial number so that if a crash site was found, the crew could be indentified. He was an advocate for a centralized department that could process data to locate missing personnel. His dream became a reality after his death in 1960, when the American government established the Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii in 1976 to include not only air crews, but all Americans who were missing in action.

Roman Conquests: North Africa by Nic Fields, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2010, 176 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $39.95, hardcover.

Roman Conquests: North Africa by Nic Fields, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2010, 176 pp., notes, index, illustrations, $39.95, hardcover.

Historian Nic Fields has written a compelling account of the Roman Army’s campaigns in North Africa, tracing the numerous battles that expanded their empire. Perhaps Rome’s greatest threats during this period were the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca and his famous son by the same name, Hannibal. The elder Hannibal once called Rome the greediest nation on earth. He was probably correct. The riches that Rome had gathered came largely at the expense of other nations, including Carthage.

The younger Hannibal had been a formidable foe as well. His daring incursion into Italy, crossing the Alps and winning an incredible victory at Cannae, where an estimated 50,000 to 70,000 Romans were killed, wounded, or captured, was a tremendous feat. Unfortunately for Hannibal, the Romans invaded his country and he was forced to return. He was soundly defeated at the Battle of Zama, primarily because of Rome’s superior cavalry tactics.

Fields has written a forceful narrative that easily takes the reader from one campaign to the next. For those with an interest in ancient warfare, this book would make a solid addition to their home library.

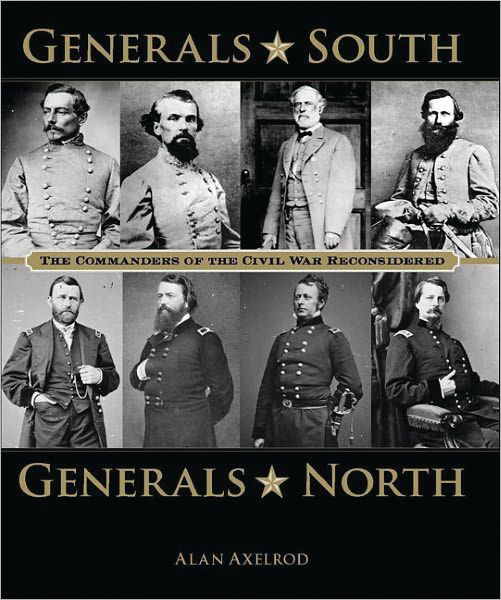

Generals South, Generals North by Alan Axelrod, Ph.D., Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2011, 311 pp., photos, illustrations, maps, $27.95, hardcover.

Generals South, Generals North by Alan Axelrod, Ph.D., Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2011, 311 pp., photos, illustrations, maps, $27.95, hardcover.

If you want to gain a greater insight into the performance of the generals on either side during the Civil War, here is a book that is perfect for your needs. By 1865, 583 generals had served for the North. Likewise, 572 wore the stars for the Confederacy. The author has taken two dozen of the best-known generals and rated them.

In his opinion, the Union side that included Ulysses S. Grant, Phil Sheridan, and George Thomas deserves accolades for its outstanding capabilities. Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Nathan Bedford Forrest rank high on his list for the South.

Ironically, Grant had a reputation as a drunkard and had failed in most everything he did after his resignation from the Army before the war. However, it was this quiet, unassuming, cigar-smoking Illinois native who brought victories in the western theater while the Army of the Potomac in the East was floundering. That all changed when Grant took charge.

A fiery Yankee hater who came onto the scene like a bolt of lightning was Nathan Bedford Forrest. With no formal military training, he nonetheless made life miserable for the Yankees with his daring raids deep beyond their lines. He proved to be so formidable an opponent that William Tecumseh Sherman called him “That Devil Forrest.” The nickname fit.

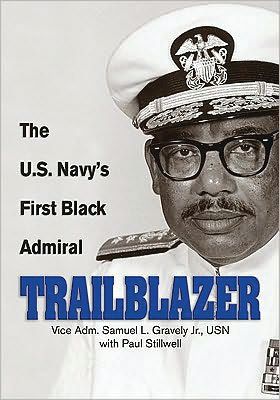

Trailblazer: The U.S. Navy’s First Black Admiral by Vice Admiral Samuel L. Gravely, Jr., USN, with Paul Stillwell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 272 pp., photos, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Trailblazer: The U.S. Navy’s First Black Admiral by Vice Admiral Samuel L. Gravely, Jr., USN, with Paul Stillwell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 272 pp., photos, index, $34.95, hardcover.

The title of this book could not be more appropriate, because that was exactly what Samuel Gravely was during his 30 years in the U.S. Navy—a true trailblazer.

Growing up as an African-American in pre-World War II Richmond, Virginia, was not easy for a young black man. Segregation was the order of the day, and opportunities for blacks were limited. However, Gravely was one of the first blacks accepted into the U.S. Navy and was commissioned an officer at war’s end. Even while wearing the uniform, he was arrested for impersonating an officer by military police while in Miami and was denied housing in Virginia during the Korean War.

Despite the racial injustice, Gravely persevered and rose up the promotional ladder, becoming the first black admiral in 1971. After his death in 2004, the Navy named a guided missile destroyer in his honor. The move prompted his wife Alma to say, “Since the Navy thought enough of my husband to build a ship for him, I am so glad you chose a destroyer. Because if you had not, be it larger or smaller, my husband would have turned over in the grave. And he would have, because he loved destroyers.”

The Big Book of Civil War Sites: From Fort Sumter to Appomattox, a Visitor’s Guide to the History, Personalities, and Places of America’s Battlefields edited by Cynthia Parzych, Globe Pequot Press, Guilford, CT, 2010, 444 pp., illustrations, maps, $27.95, hardcover.

For those Civil War buffs who plan on taking to the open road to visit battlefields, here is a book you may seriously want to consider taking along on your journey. Not only does it give the reader a synopsis of a particular battles, events leading up to it, leaders of both the Northern and Southern armies, but it also includes points of interest, restaurants, lodgings, and day trips.

For those beginners in Civil War history who want to learn more, the book contains a glossary to assist them with unfamiliar terms. The editors suggest that you call ahead to obtain current information about hotels and restaurants.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments