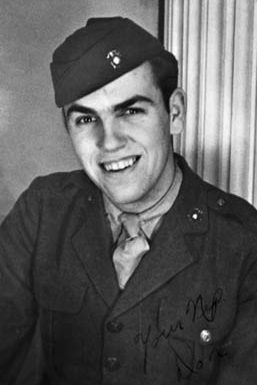

By Durk Steed

He wore the clothes of one of Tarawa’s most well-known and decorated heroes, but his name will not be found in any history book. Hurtled against hell, this unsung American drove a first-wave amtrac into the eye of the Tarawa hurricane, landing on the deadliest beach of the Marines’ bloodiest across-the-reef landing of World War II. He is Don Crain, and this is his story.

Don Crain turned 17 in October 1941 and went straight to the Marine Corps recruiting station to celebrate. “My three brothers, all taller and stronger than me, couldn’t pass the Marine physical for one reason or another. I passed, but before the war the Marines had a quota system. They only allowed 10 or 12 guys a month to sign up from Montana. I got turned down in October, November, and again in December.”

After Pearl Harbor the quota system was dropped, and Don’s birthday wish was finally granted. In January 1942, along with 22,686 other young men across the country, Don enlisted in the United States Marine Corps. Six weeks of boot camp in San Diego followed, and Don became a United States Marine. He expected to be thrown into the fight against the Japanese, but in his wildest dreams he could not foresee his role in that fight and the terrific human cost required.

Assigned to B Battery, Special Weapons Platoon, 2nd Marine Division, Don shipped out to New Zealand in October 1942. The 22-day voyage aboard the transport President Monroe was filled with monotony punctuated by one heart-racing day. “At some point south of the equator we saw ships on the horizon,” Don remembered. “We thought it was the Japanese Navy! Then, the loudspeaker blared out that we were looking at U.S. Navy ships that had just picked up Eddie Rickenbacker.”

Rickenbacker, the leading American fighter ace of World War I, had been adrift for 24 days after a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bomber he was a passenger in was forced to ditch. When the Monroe arrived in New Zealand, “We took one look, saw all the girls, and loved the place,” recalled Don.

A Bold New Tactic: The LVT Assault

In July 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered the 2nd Marine Division to seize Tarawa atoll. The 2nd Division’s Operations Officer, Lt. Col. David Shoup, faced two formidable challenges: concentrated, fortified Japanese defenses along the beach and a wide, shallow fringing reef that could not guarantee the three feet of water required by the Marines’ ship-to-shore mainstay, the LCVP (landing craft, vehicle, personnel), or Higgins boat.

Shoup had a bold idea. Could the Marines’ first-generation amphibious tractor—primitive, thin-skinned, underpowered, and previously used only to haul supplies behind the lines—be laden with Marines and used to spearhead an amphibious assault? Shoup’s daring question was to transform Don Crain’s life and the Pacific War.

While the Marines drank deeply of Kiwi hospitality, Dave Shoup busily planned for Tarawa. Committed to an LVT (landing vehicle, tracked) assault, he needed Marines to crew the amphibious craft in its daring new role. In August 1943, Don Crain was transferred into C Company, 2nd Amphibious Tractor Battalion. Don had never seen an amphibious tractor, but sparks flew on his first date with the 23-foot-long, $35,000 craft.

“I found the vehicle fascinating,” he recalled. Don embarked on a crash course, training as an LVT-1 driver. In less than three months, he would find himself in the driver’s seat of a first-wave amtrac clawing his way across a coral reef into the muzzles of Japanese guns at Tarawa.

“They Told Us it Would be a Piece of Cake”

On a dock in Wellington, New Zealand, in late October, Don’s LVT-1, along with nine other amtracs scheduled for the first wave, was hoisted onto the weatherdeck of the assault transport Virgo. The tractor was field upgraded for the coming assault with three machine guns, ¼-inch steel to protect the cab, and a white “41” painted on the stern and cab sides. Next stop were two days of invasion rehearsal in Efate, New Hebrides, where one of the LVT-1s broke down. Don helped tow it back to the Virgo.

The Virgo departed Efate on November 13, and the next day the assault Marines learned that their target was Tarawa. “A few guys had never heard of New Zealand before we got there. None of us had ever heard of Tarawa. On D-minus-2 the lieutenants and captains gave us a preinvasion talk. They said that after all the bombing and shelling there wouldn’t be a Jap left alive. If there were, they’d all be crying for their moms. They told us it would be a piece of cake.”

Don’s orders were to transport 20 Marines of the 2nd Regiment in the first wave and land them on Red Beach 2. It sounded simple enough, but intelligence gathered on Tarawa’s defenses revealed that Red Beach 2 was bristling with coconut log-reinforced strongpoints, concrete pillboxes, sandbagged positions atop a stone seawall, concealed rifle pits, a double apron of concrete tetrahedrons, and barbed wire strung across the reef. Elite Japanese Imperial Marines of the 7th Special Naval Landing Forces manned the defenses. Their orders were to annihilate the Americans on the beach.

LVT 41 Advances Toward the Beaches

Shrouded in the darkness of the early morning of November 20, 1943, Virgo arrived off Tarawa. “I still remember praying, trying to sleep, and having a meal of steak and eggs,” said Don.

LVT 41 was hoisted over the side, and Don guided her to the open water rendezvous point. There, assault Marines cross-decked from Higgins boats into amtracs. Plans called for 18 assault Marines in each LVT-1. In LVT 41, 20 Marines packed in as tight as sardines. The riflemen, fully combat loaded, stood shoulder to shoulder in the small cargo hold. The LVT’s low freeboard and the ocean swells combined to soak the Leathernecks.

At 6:48 am, the troop-laden LVTs formed into three long, single-file lines, and 42 LVT-1s of the first wave bobbed on the starboard while two lines of 24 and 21 LVT-2s composing the second and third waves scudded along the port side. Crain did not know it at the time, but LVT 41’s position to the right of center in the first wave line was to throw him into the teeth of the most dangerous section of Tarawa’s most deadly beach.

Shepherded by the minesweeper Pursuit’s searchlight, Don fought a headwind and current to navigate through the lagoon passage. The distance from Virgo to the line of departure was almost nine miles, the longest ship-to-shore transit of any invasion in the Pacific War. Hunkered for hours at the controls of LVT 41, Don had no idea that he was approaching the fiercest maelstrom of concentrated fire that the Japanese had yet to throw at the Marines in the Pacific.

“Lock and Load!”

Beginning just before dawn, Navy battleships unleashed an apocalypse. Sunrise lifted the curtain on a theater of destruction. For almost three hours, 16-inch shells, sounding like freight trains flying through the air, rained down on the little island, exploding in eruptions of sand and flame. Carrier aircraft strafed and bombed when the battleships took a rest. Don first caught sight of the islet of Betio, one of Tarawa’s many small spits of land, through the narrow slit of the cab’s appliqué armor plating. The Navy’s promise to blast Tarawa into the sea seemed to be coming true before his eyes, bolstering his spirits. Burning and smoking, Betio looked like a funeral pyre.

Churning shoreward in his LVT, it seemed impossible that any Japanese could still be alive. Yet, Don’s trusty Springfield M1903 rifle was stored on the deck behind him. Lieutenant Bonnie Little stood directly behind, manning one of the cab’s .50-caliber machine guns. In a letter to his wife, Little had written, “The Marines have a way of making you afraid—not of dying —but of not doing your job.”

Don stared as the tropical breeze blew the pall of smoke away. Momentarily, a slight chill ran down his spine. The island floated above the lagoon, defiant and menacing. Ashore, out of Don’s sight, Japanese Marines, hidden safely in their bunkers and pillboxes, stared down their gunsights waiting for the Americans to come into range.

At 8:24 am and 6,000 yards from shore, the column of first-wave LVT-1s, white frothing wake spewing behind, executed a right turn and crossed the line of departure. Behind him in the cargo hold, Don heard the command, “Lock and load!” Riflemen slammed eight-round clips into M-1 Garand rifles and pushed safeties forward. Lieutenant Little pulled back on his machine gun’s cocking lever to catch the belt, pulled back again, and released a second time to advance the first round into the chamber. The assault Marines aboard LVT 41 shared a common duty to get ashore quickly, move forward, defeat any surviving enemy, and secure the island. Don bore another duty: to drive his human cargo to shore.

Squeezing every bit of power out of the 150-horsepower Hercules engine, Don coaxed 3.5 knots from LVT 41. He steered to the west of the long, central pier, aiming for Red Beach 2. The current pulled him farther right.

For several minutes, there was an uneasy calm. Both sides held their breath and their triggers. The Japanese waited for the LVTs to come into range. The Marines had no visible targets. The Navy ships and planes stopped firing to avoid friendly fire accidents.

Driving Into “The Pocket”

As Don closed to within 3,000 yards of shore, Japanese air bursts peppered the amtrac. Illusions of an uncontested assault vanished. Don adjusted his helmet, glancing at his radio operator on his left and his assistant driver on the right. Contact with the reef, the reason for the LVTs’ presence, was at hand.

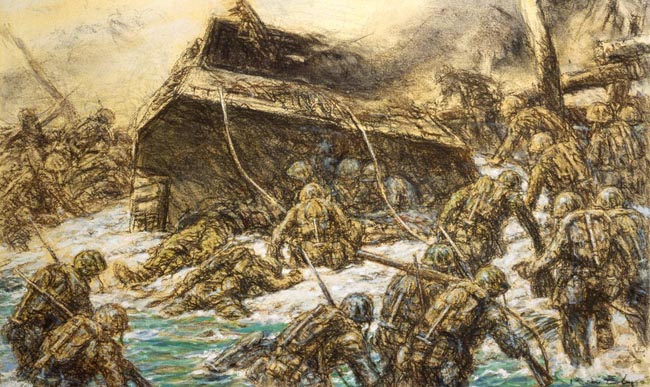

In hindsight, the Americans placed false confidence in their preinvasion bombardment, but the Japanese placed too much confidence in Tarawa’s reef. In stunned amazement, the Japanese watched as the gangly amphibians did not stall at the reef but waddled out of the lagoon, clawed onto the shallow sand and coral of the fringing reef, and churned forward. The Japanese had never seen such vehicles.

The Japanese regained their senses and swatted violently at the “spiders” with a wall of angry steel. In doing so, the shortcomings of the preinvasion bombardment became obvious. Plenty of Japanese were alive and plenty of their guns intact. Without air or naval fire to keep the Japanese buttoned up, Don felt like a duck in a shooting gallery. His amtrac clawed across the shelterless reef, its speed increasing slightly as its tracks gained traction on the coral and sand.

“The reef was about 800 yards out. The pier was to our left. I could see bullets coming through our bow and a lot coming through the side. We were taking a lot of fire from the hulk of a ship aground to our right. The fire killed both the radio operator and the assistant driver.”

Pushing and pulling on the steering levers, Don piloted LVT 41 toward the cove separating Red Beaches 1 and 2. Directly ahead lay a particularly pernicious point of resistance dubbed “the Pocket” by Marines. The Pocket was to withstand three full days of Marine attacks and was the last position of organized Japanese resistance to fall on Tarawa. Unknowingly, Don was driving LVT 41 into the eye of the Tarawa hurricane.

LVT 41 Wiped Out

“After Tarawa, the maintenance officers told us that they had tested the armor plating installed on the amtrac cabs in New Zealand. An M-1 Garand’s bullet could go right through it. We were never told that before the invasion. It would have been too demoralizing.”

Marines in the cargo hold of the LVT did not even have the scant protection of the cab’s armored plates. Lieutenant Little, who had written to his wife that he was afraid of not doing his job, died proving his conviction to his words. “He was firing one of the machine guns, but I was busy driving and couldn’t see what was going on behind me,” Don said.

With a dead crew member on each side, Don gripped the steering levers as LVT 41 churned across the reef and toward the Pocket. Every yard of the way, punishing hits from machine guns and near misses from 75mm dual-purpose guns pummeled the tractor.

“We got about halfway across the reef; then, the amtrac’s engine just stopped. It was dead.” So focused on his job of driving the LVT to the beach, Don was unaware that the other Marines in the cargo hold had been killed. He didn’t know whether they died one by one as LVT 41 clawed across the exposed reef, or whether they died all at one time. He only knew that when he crawled out between the cab’s two dead Marines, the macabre sight of 18 more dead Marines met him in the cargo hold.

“I was one of only three to get out alive—the maintenance sergeant, one Marine rifleman, and myself. The maintenance sergeant and the rifleman were both wounded. We had no weapons. We jumped out over the side and into the water and went to the back of the tractor.”

Everything in the cargo hold, both humans and equipment, had been destroyed.

“I Recall About Six or Seven Percent of Tarawa… I Block Out the Rest”

The history books accurately recount that Tarawa’s LVT gamble was a tactical success. Only eight of the 42 first-wave LVTs were knocked out before reaching the beach. Don Crain knew all too well what it meant to be aboard one of those eight. “There were 23 of us in that tractor, but only three of us got out alive and lucky me without even a scratch. The dear Lord protected me.”

Ironically, Don, a driver of a 20th-century amphibious assault innovation, ended up splashing through the surf to shore just like his Marine predecessors in their debut amphibious landing at Nassau in 1776. Unwilling to abandon the two wounded Marines, Don kept them alive until dark and then got the pair to a low seawall.

Ashore, Don joined the other Marines in wresting the island from the Japanese in a brutal 31/2-day brawl that cost both sides dearly and practically annihilated the Japanese.

“I can recall about six or seven percent of Tarawa,” Don said. “I block out the rest. What I still remember is the incredible noise and awful stench from dead bodies. You just can’t forget that sort of thing. I also remember a Marine shot in the throat and unable to breathe. A corpsman cut an opening in his trachea and inserted a thermometer case to get him air and save his life.”

High Casualties on Tarawa

When the dust settled after the 76-hour slugfest, only 17 of the over 4,000 Japanese defenders remained alive. The Marines paid dearly for the victory with 1,027 killed and 2,292 wounded. Three of the worst hit Marine units were involved in assaulting Red Beach 2. Don’s 2nd Amtrac Battalion suffered 50 percent casualties, and by battle’s end 90 out of its 123 amtracs employed had been knocked out.

Of the eight LVT-1s destroyed in the first wave on all beaches, six of those were destroyed attempting to land on Red Beach 2, Don Crain’s LVT 41 among them. Finally, three of the four Medals of Honor awarded for valor at Tarawa went to Marines on Red Beach 2, to Lt. Col. Shoup, Lieutenant William Deane Hawkins, and Sergeant Bill Bordelon. Yard for yard, Tarawa was the Marines’ bloodiest across-the-reef landing of World War II, and Don’s attempted landing site of Red Beach 2 its bloodiest beach.

Alexander Bonnyman’s Clothes

“The island stunk and reeked,” Don said. The odor of almost 6,000 decomposing dead could be smelled miles offshore. Expecting to return to the Virgo on D-day, Don came ashore with only the clothes on his back. That assault uniform was now in tatters, so Don went in search of clean clothes.

“I found Lieutenant [Alexander] Bonnyman’s pack. Inside was a fresh pair of dungarees,” he remembered. Don put on the clothes not knowing who Bonnyman was, only that he was dead. After the war, when Bonnyman’s name became legendary and synonymous with the highest of courage and sacrifice at Tarawa, Don attended a ceremony at Hawaii’s Punchbowl Cemetery.

“I met Lieutenant Bonnyman’s sister and told her about the clothes,” he said. “She said she was thrilled that her brother was helping Marines even after he died.” Bonnyman was awarded the Medal of Honor for his role in capturing the large sand-covered bombproof behind Red Beach 3. Clad in Bonnyman’s clothes, Don remained on the island for a total of 19 days helping to salvage LVTs and unload the Army’s garrison troops.

Immediately after the battle, press coverage of the role of the LVTs was censored to hide the Marines’ new tactical innovation from the enemy. Don went on to survive an explosion at Pearl Harbor among LSTs loading for Saipan, earned a Bronze Star at Saipan for action in his LVT-2, and made 14 shuttle runs on Tinian.

Bonnie Little is my uncle. Although he was killed at Tarawa before I was born, it was always clear to everyone in my family that he had proudly joined the U.S. Marines fully understanding the ultimate sacrifice that would likely be required. To this day he remains a true hero in our family.

Thank you Lord. For this greatest generation.

Semper fi

Please give proper attribution to the banner photo you used of the LVT collection area. This photograph was taken by my grandfather Arthur John Strenge 2nd Marines.

I believe the photo you are referring to is an official Marine Corps photo from the collection now held at the National Archives. Was you grandfather an official Marine Corps photographer?

My uncle Alexander Peña fought in this battle,3rd battalion 6th marine regiment 2nd marine division, Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan and Tinian, He was KIA July 30th 1944 on Tinian, the island was declared secure Aug 1st, those brave valient men who fought at Tarawa will not be forgotten,heroes, all of them..God Bless America!!

Donald Crain is my grandpa he passed a few years back. I miss him so much. it is always neat to find articles about him. he was a true hero and patriot until his last breath. I was lucky enough to hear this story and many more from him myself, I miss those talks. Thank you for keeping my grandpa stories alive.

As I recall reading, Tarawa was one of those islands that was later fiercely debated over as to whether its occupation by American forces was necessary to defeat Japan. At the time, Admiral Chester Nimitz felt strongly about the necessity of capturing the island. After the battle and the number of killed and wounded Americans was tallied, Nimitz and others had deep misgivings of what had transpired. For the remainder of the war in the Pacific, Tarawa would be a painful reminder to Nimitz and other Navy and Marine brass of the high cost in lives to island hop to the Japanese mainland. It saddens me to read these stories and I mourn all these years later for our military personnel who died in these battles, especially ones that were not really necessary; they were all young men, not even in the prime of their lives yet, but were willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for their country. We are so lucky to have had them when they were so needed!