By Jon Diamond

Many students of World War II history know General Sir Claude Auchinleck as the Commander-in-Chief Middle East, who, after taking over for General Sir Archibald Wavell in late June 1941, oversaw the fluctuating fate of Britain’s Eighth Army while combating German General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps during Operations Crusader and Gazala.

It was after General Neil Ritchie’s humiliating defeat along the Gazala Line that Auchinleck took over direct control of the Eighth Army and fought Rommel to a standstill in July 1942 at the First Battle of El Alamein. However, this Indian Army general had an eventful career leading British and Allied troops in Norway in the spring of 1940 as well as in the British Isles from July through November 1940 before his return to India to become commander of the Indian Army in January 1941. Those early Auchinleck commands were quite uncharacteristic for an Indian Army general given the rivalry of that organization with the regular British Army.

“The Auk”

Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck, nicknamed “the Auk,” was born on June 21, 1884, in Aldershot, England. He was the eldest child of Lt. Col. John Claud Alexander Auchinleck of the Royal Horse Artillery, stationed at Aldershot. The younger Auchinleck was of Anglo-Irish-Scottish descent, which was to characterize the origins of many a noteworthy British Army officer.

When Auchinleck was a year old, his father returned to Bangalore, India, to command the Royal Horse Artillery there. In 1888, while his father was serving in the Third Burma War, Auchinleck returned to England with his mother and siblings. His father, having retired from the Army in 1890, died two years later from a form of anemia putatively contracted during his Burmese service. As a result of his father’s death, his childhood and early adulthood bordered on poverty.

In the fall of 1896, Auchinleck attended Wellington, located near Sandhurst, at a drastically reduced fee since he was an officer’s son. In 1901, he sat for the entrance examination for the Royal Military College at Sandhurst since his lackluster mathematics performance at Wellington precluded the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, the training ground for gunners and engineers. He placed 45th on the Sandhurst examination, taking the last place allocated to the Indian Army, and entered the academy in 1902. He was among 30 cadets receiving their commissions in the Indian Army the following year.

With five other officers from Sandhurst, 2nd Lt. Auchinleck was temporarily sent to the 2nd King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (KSLI), a British battalion having recently seen action in South Africa. After a winter attached to the British regiment, he joined the 62nd Punjabis, an Indian Army regiment, in April 1904, to which he was permanently posted.

Auchinleck rose to the rank of captain during 11 years of peace in India, which were shattered by World War I. Up to that point, he had never fired a shot in anger. However, he did learn a number of local languages and bonded with his troops by being able to converse fluently with them.

Auchinleck in World War I

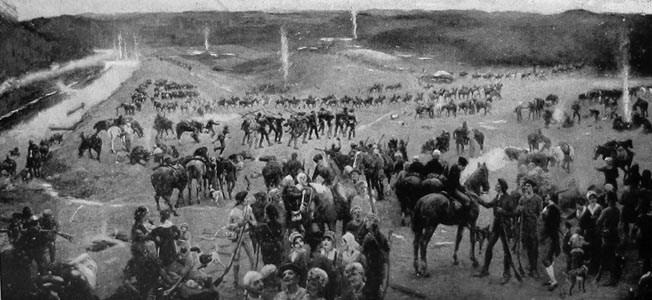

Auchinleck, initially bound for France, was detoured along with his 62nd Punjabis (as part of the 22nd Indian Infantry Brigade) to Suez and the defense of the area around the canal from Britain’s new enemy, Ottoman Turkey. It was in early February that Auchinleck received his baptism of fire as the Turks attempted to cross the Suez Canal at Ismailia. After defeating this Turkish attempt to take the Suez Canal, Auchinleck’s regiment embarked for Aden in July 1915 to successfully eject the invading Turks in that Protectorate.

In December 1915, the 62nd Punjabi Regiment was ordered to the Persian Gulf and Mesopotamia, and thus Auchinleck avoided the carnage of Gallipoli, the brainchild of his fellow Sandhurst cadet, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill. Disembarking at Basra on January 7, 1916, for the offensive up the Tigris River to Baghdad, Iraq, Auchinleck, now an acting major and second in command of his regiment, witnessed nearly a 50 percent casualty rate during a month of campaigning against the well-entrenched Turks. A second major attack, this time along the right bank of the Tigris to relieve Kut in early March 1916, also failed largely due to a background of hasty and unimaginative planning and administrative incompetence.

Auchinleck summed up his regiment’s condition in April 1916 as “exhausted, decimated and with our morale badly shaken.” The chaos in logistics he experienced was to foreshadow the command role Auchinleck inherited during the Allied attack on Norway in 1940.

By the autumn of 1917, Auchinleck was regarded as an officer of promise and meritorious achievement, and he became the brigade major of the 52nd Brigade as part of the new 17th Indian Division. Auchinleck was mentioned in dispatches and received the Distinguished Service Order in 1917 for his service in Mesopotamia. He was promoted to major in January 1918.

Interwar Expeditions in the Middle East and India

Soon after the armistice, Auchinleck became a general staff officer (GSO) 2 with the division garrisoning Mosul, Iraq. In August 1919, as GSO 1 of a division, he was ordered to pacify Kurdistan. For his excellent staff work he was again mentioned in dispatches and made a brevet lieutenant colonel. At the end of 1919, he was offered a vacancy at the Staff College at Quetta, which was recognized as a “gateway to advancement” in the Indian Army. There, he was outstanding among the younger Indian Army officers who had survived the Great War.

In 1923, Auchinleck was stationed at Simla, India, as a British staff officer, and after four years he returned to his regiment, now renamed the 1st Battalion, 1st Punjab Regiment. In 1927, Auchinleck, having been recognized as “one of the outstanding Indian Army officers of his generation,” was posted to the Imperial Defence College (IDC). While at the IDC, Auchinleck made a valuable friendship with General Sir John Dill, the chief instructor there. After his stay at the IDC, Auchinleck returned to his regiment in India. At the end of 1928, Auchinleck was appointed to command his own battalion. In February 1930, he returned to Quetta as GSO 1 at the Staff College with the rank of full colonel. It was a two-year course, and he was in charge of 30 officers in the junior division in their first year.

Later, in command of the Peshawar Brigade, Auchinleck led a short punitive expedition against the Mohmands in 1933. For this expedition, he was awarded the title of Commander of the Bath (CB). In 1935, during another expedition against the Mohmands as a junior brigadier, he made a close professional association and friendship with the forces’s senior brigadier, Harold Alexander. After this expedition’s successful conclusion, he received the Companion of the Order of the Star of India (CSI) and another mention in dispatches. Upon being promoted to major general, Auchinleck handed over command of the Peshawar Brigade to Brigadier Richard O’Connor, another Wellington graduate.

From 1936 to 1939, Auchinleck was the Deputy Chief of the General Staff (DCGS), India and Director of Staff Duties in Delhi. In early 1938, Colonel Eric Dorman-Smith, another young staff officer of high intellect and professional achievement, was appointed Director of Military Training at Army Headquarters in Simla. There, both his work with Auchinleck and their mutual habit of long morning walks forged a strong bond of friendship and professionalism. This relationship would later flourish in the Western Desert in 1942, as the duo oversaw the successful defense of Egypt during the First Battle of El Alamein, after the defeat along the Gazala Line, when the victorious Afrika Korps was threatening to capture the Suez Canal and the Middle East.

From Stitzkrieg to Blitzkrieg

In July 1939, Auchinleck and his family visited the United States as war clouds were looming over Europe. While he was sailing back to India, war broke out. Soon thereafter he took up a new position as commander of the 3rd Indian Division. During the Phony War, he continued to train his troops. In January 1940, he was ordered to return to England to take command of the IV Corps before its deployment to northern France around Lille as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in June of that year. The IV Corps was composed of British Regular and Territorial Army units, with most of the formation being untrained. A “Sepoy General” was now in charge of a large British Army force.

Auchinleck was isolated and lonely in his new IV Corps command, largely because the British Regular Army in the higher officer ranks was a tightly knit and closed community. Auchinleck also felt somewhat inferior to the Regular Army officers of the conventional English upper class because of the relative poverty of his youth and adulthood. To Auchinleck’s endearing credit, he lacked the snobbishness of the British Regular Army. Instead, he exuded professionalism, which was an anathema to English upper class society. With his focus on professionalism, he shared a common trait with a junior competitor, future Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.

On April 9, 1940, the Nazis, who had a non-aggression pact with Denmark, nevertheless invaded and forced a surrender of that country within hours. Also on that date, the Germans seized Oslo, Stavanger, Bergen, Trondheim, and Narvik in Norway despite that country’s neutral status. The Allies decided to counterattack with the most suitable objective being Narvik, even though it lies within the Arctic Circle. This strategic decision was based upon the recommendation of the British Military Coordination Committee under the chairmanship of none other than Winston Churchill, again serving as First Lord of the Admiralty.

The objective was to establish a naval base for the Allies in the far north of Norway, which could be a staging area to seize the Galliväre iron ore fields in Sweden. To achieve this, Narvik had to be retaken. Although other operations were proceeding badly against the Germans in central Norway, the Narvik attack was to deliver the major thrust against the Nazis. As events unfolded, it did no better than the more southern operations despite a British naval victory over a German destroyer force in the Ofot Fiord leading into Narvik.

Evacuation Under Auchinleck

On April 28, Auchinleck was ordered to report to the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS), General Sir Edmund Ironside. The CIGS, who was soon to be replaced by General Sir John Dill, informed Auchinleck that he and part of the IV Corps staff were going to Narvik. To emphasize the divide between the British Regular Army and the Indian Army, Ironside gave Auchinleck a backhanded compliment by describing him as “the best officer India had, who was not contaminated by too much Indian theory.”

Auchinleck replaced the local ground forces commander in northern Norway, Maj. Gen. Pierse J. Macksey, who was faulted for being too deliberate in his approach to secure the port of Narvik. However, Auchinleck could see no way to speed up the British advance.

There were reasons for the faulty performance of the BEF under Auchinleck’s command. There were few reliable maps of the area, and RAF air cover was spotty at best early in the campaign. While Auchinleck was at sea headed for Norway, there was a two-day debate in the House of Commons on the conduct of the Norway campaign that led to the ouster of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s government.

The day before Auchinleck’s arrival in Norway, the Nazi blitzkrieg through the Low Countries had commenced, and Churchill had been appointed prime minister. With attention diverted now to northern France and Belgium, it is easy to draw the conclusion that Narvik had turned into almost a backwater. Near the end of May, it was determined that Allied forces in northern Norway were to be evacuated. However, Narvik should be captured to facilitate the operation.

With Narvik in his hands, Auchinleck had to throw all of his energy and leadership to the task of evacuation with the minimum possible casualties. In his correspondence to Dill on May 30, Auchinleck commented, “The news from France is grim and every one is depressed by it, naturally. However, there is no sign of defeatism so far as I can see. This is a queer show into which you have put me!… One feels a most despicable creature in pretending that we are going on fighting, when we are going to quit at once.”

The evacuation began on the night of June 3. Cloud cover, Auchinleck’s determination to keep British antiaircraft guns in action to the last, and the RAF’s ceaseless sorties from its base at Bardfoss all contributed to a smooth military withdrawal, which was completed by June 7. Auchinleck had been on Norwegian soil for just under four weeks. The Auk realistically drew his own historical analogy about the Napoleonic Wars in his correspondence with Dill. “We are in the same position as were Napoleon’s adversaries when he started in on them with his new organization and tactics! I feel we are much too slow and ponderous in every way.”

Lessons From Norway

Auchinleck had learned some pragmatic lessons from his experiences in northern Norway. First, “To commit troops to a campaign in which they cannot be provided with adequate air support is to court disaster.” Second, “No useful purpose can be served by sending troops to operate in an undeveloped and wild country such as Norway unless they have been thoroughly trained for their task and their fighting equipment well thought out and methodically prepared in advance. Improvisation in either of these respects can lead only to failure.”

Two paragraphs of Auchinleck’s report that was completed on June 19, 1940, and subsequently printed for the War Cabinet in March 1941, had been suppressed during the war and were only to reappear in July 1947. “The comparison between the efficiency of the French contingent and that of British troops operating under similar conditions had driven this lesson home to all in this theatre, though this was not altogether a matter of equipment. By comparison with the French, or the Germans for that matter, our men for the most part seemed distressingly young, not so much in years as in self-reliance and manliness generally. They give an impression of being callow and undeveloped, which is not reassuring for the future, unless our methods of man-mastership and training for war can be made more realistic.”

The Construction of V Corps

Auchinleck would have his chance to train British troops in southern England, North Africa, and India where they would all prove their mettle and receive the Auk’s accolades.

After the Norwegian debacle, Auchinleck was instructed to form V Corps for the defense of southern England. This would be an understrength corps of two divisions, virtually without heavy equipment, along a stretch of about 100 miles. Auchinleck observed firsthand that the British troops in Norway were inexperienced and the new V Corps would be no better off. Hard training lay ahead if a Nazi invasion were to be either repelled or contained.

On July 19, 1940, Auchinleck received another promotion barely a month after his orders to the V Corps assignment. He was now to take over Southern Command. The V Corps would become the domain of Lt. Gen. Montgomery, back from divisional command in the failed BEF operation in Flanders. The two were at odds continuously, with the critical nature of the times preventing Auchinleck from sacking Montgomery. Auchinleck, like Rommel four years later in Normandy, wanted to meet the German invasion on the beaches; however, Montgomery argued vociferously for maintaining strength in reserve behind the beaches to destroy the Germans after they had secured a weak lodgment.

Auchinleck was also praised for the manner with which he constructed the Home Guard, which eventually became a reasonable military asset rather that a militia’s mob. Unfortunately, many postwar accounts give Montgomery credit for the development of Southern Command and the Home Guard, even though it was Auchinleck who had laid the foundations for the hard training in Southern Command. Lt. Gen. Alexander took over Southern Command when Auchinleck was appointed commander of the Indian Army in November 1940.

Auchinleck’s Return to South Asia

One of Auchinleck’s first moves as Indian Army commander in early April 1941 was to send several Gurkha and Sikh elements of the 10th Indian Division to secure the oil pipeline terminus to the Persian Gulf at Basra, Iraq, and to set a staging point to mount operations from there to Baghdad and crush the Rashid Ali rebellion. Other troops from this division, which were originally earmarked for transport from India to Malaya, were maneuvered by Auchinleck to Basra with the 21st Indian Infantry Brigade, arriving on May 6, 1941, followed by 25th Indian Infantry Brigade’s landing there at the end of May.

Auchinleck’s move was in conjunction with Churchill’s ordering Field Marshal Archibald Wavell to provide a relief force (Habforce) from Palestine to lift the siege of RAF bases in Iraq in order to reclaim Britain’s treaty rights from the insurrectionist Iraqi regime. Auchinleck’s actions in Iraq pleased the prime minister. Churchill wrote to Auchinleck on May 14, 1941: “We are most grateful to you for the energetic efforts you have made about Basra. The stronger the forces India can assemble there the better…. We are, therefore, confined at the moment to trying to get a friendly Government installed in Baghdad and building up the largest possible bridgehead at Basra.”

The prime minister further wrote of Auchinleck: “When after Narvik he had taken over Southern Command I received from many quarters, official and private, testimony to the vigour and structure he had given to that important region. His appointment as Commander-in-Chief in India had been generally acclaimed. We had seen how forthcoming he had been in sending troops to Basra and the ardour with which he had addressed himself to the suppression of the revolt in Iraq.”

For an Indian Army officer, Auchinleck had performed admirably in Scandinavia during the assault on Narvik and its subsequent successful withdrawal, as well as in England where he built up Southern Command to become a realistic force to contest a Nazi invasion on the beaches. Furthermore, prior to his assignment as Commander-in-Chief Middle East, for which he is most famous, he had shown initiative when directing his Indian Army troops to seize Basra from Iraqi insurgents.

However, the sternest test for the Auk was to come against Rommel in North African desert.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments