By Kevin O’Beirne

Ever since Julius Caesar’s legions conquered Gaul, opposing armies have built temporary fortifications, or fieldworks, during campaigns in the open countryside. In the modern age, such fieldworks were perfected first during the Civil War. By the spring of 1864, Americans on both sides of the conflict had discovered the life-saving nuances of trench warfare, something that would cost their European counterparts hundreds of thousands of lives to learn for themselves half a century later.

When no one was actively shooting at them, Civil War soldiers despised the hard physical labor required to construct fieldworks. As one officer of the 2nd Michigan Infantry recalled, “Soldiers would rather march all day than shovel for an hour.” Another Union soldier, Sergeant George Tipping of the 155th New York, wrote to his wife from Petersburg, Va., in September 1864: “We now handle the spade and shovel in place of the musket. There are 3,000 of us [who] go out every day to build forts and rifle pits. Twenty men would do more work in one day than the whole 3,000 men.” Another Yank, James Ford, grumbled about building fieldworks at Pipe Creek, Md., during the Gettysburg campaign. “Well we tried what you call soldiering for two days. I think that I should like it very well nothing very bad about it only that spades come trump pretty often.”

Enemy bullets, however, were a terrific motivator of men, as related by a bluecoat named Van Dyke in the aftermath of skirmishing along the Rapidan River in November 1863: “It is hard to get the men to dig for 10 minutes when we are not at the front. But when the shot and shell begin to fly, they dig like woodchucks, even though they do not carry spades. [I]n a short time they are safe behind strong works.”

Regardless of their dislike for constructing fieldworks, soldiers certainly preferred fighting behind them, as New Yorker Richard T. Van Wyck noted of his regiment’s works on Culp’s Hill at Gettysburg. “Our position there was of a most favorable kind,” Van Wyck wrote. “We were little exposed and did terrible execution upon the Rebs.” And a member of the Union 2nd Corps recalled after the Battle of the Wilderness: “The rapid fire of the foe had but slight effect on our line, behind its bullet proof cover, over the top of which we, with deliberate aim, hurled into [the Confederate] regiments an incessant and most deadly fire.”

Civil War fieldworks were actually trench systems, and were much more complex than a mere trench made by excavating material and tossing it out in front of the trench. Fieldwork systems included cleared fields of fire, obstructions, and barricades, and outer works in front of the breastwork proper, together with gun positions, redoubts, covered ways, and other protective features on the defenders’ side of the line.

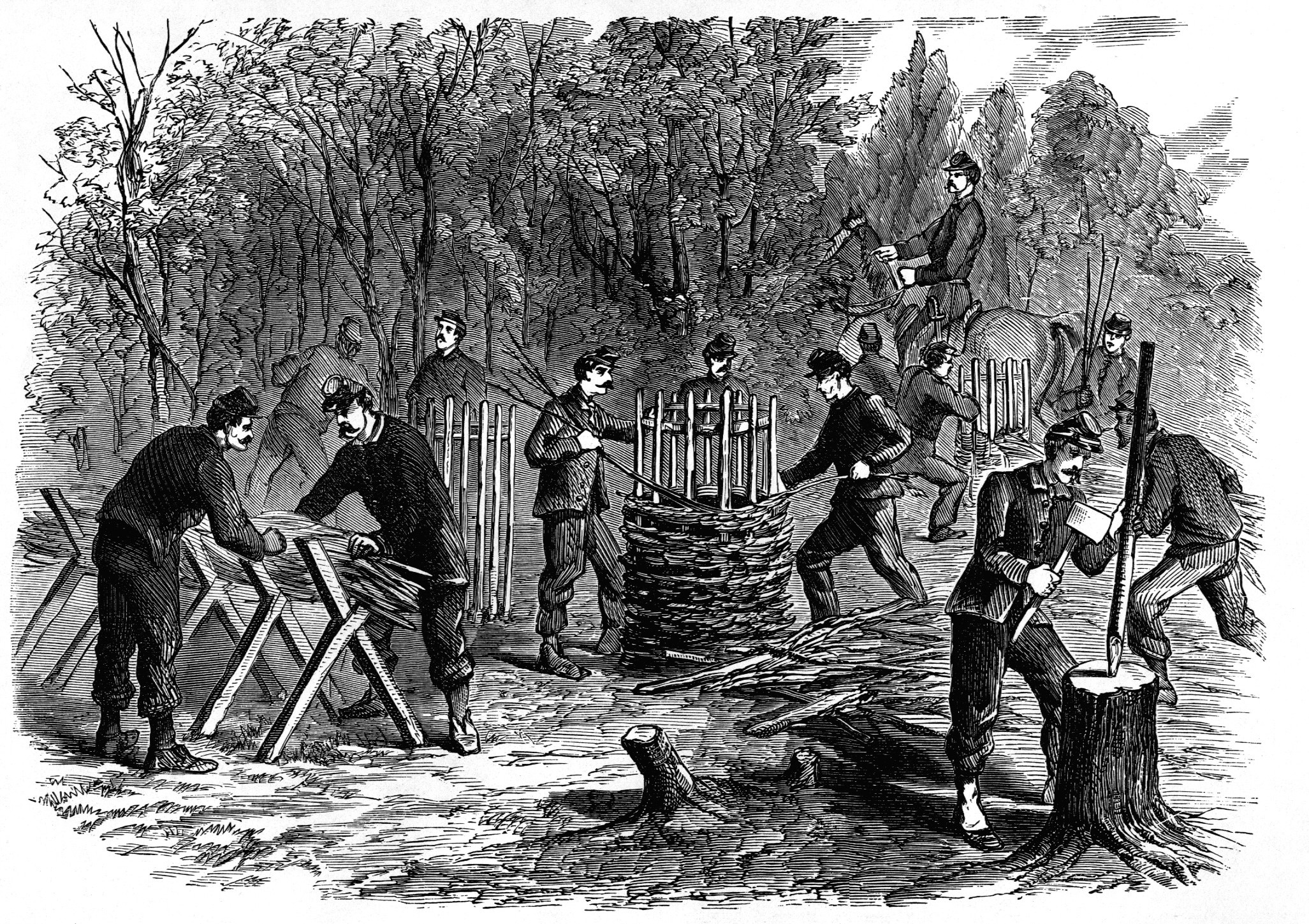

When built under fire, the initial line of fieldworks was often selected by regimental field and line officers, and construction was supervised directly by them. It was not uncommon for engineer officers to later adjust portions of the line to better positions. Non-engineer officers also sited works at isolated posts. The majority of fieldworks were constructed by rank-and-file enlisted men wielding a variety of specially designed and improvised hand tools. A small number of men in each company might be designated as pioneers, temporarily assigned to fatigue duties such as fieldworks construction and road work. Pioneers were not permanent units, and men were selected for such details because they were good ax-men or possessed other construction-related skills.

Some common—but not the only—features of a Civil War fieldworks system included rifle pits, abatises, chevaux-de-frise, ditches, embankments, parapets, breastworks, trenches, revetments, head logs, traverses, sally ports, redans, lunettes, and redoubts. Rifle pits varied in size, from what might be called a foxhole to complete fieldworks. Most were advanced fieldworks meant for pickets, usually hundreds of yards in front of the main line.

An abatis was an obstruction placed in front of the breastworks, well within the defenders’ rifle range. The abatis included the tops of pine trees stripped of leaves and smaller branches and sharpened to points using hatchets and axes, with the points placed towards the enemy. It was usually about breast-high, and was low enough for its defenders to shoot over and into. The obstructions were interlocked with each other to create a formidable barrier.

Chevaux-de-frise were X-shaped, movable obstacles consisting of a horizontal beam about 10 to 12 feet long and one foot in diameter, with two opposing, diagonal rows of sharpened, 2-inch-wide, 10-foot-long wooden rods inserted it. Chevaux-de-frise were placed at important positions in front of fieldworks and could be used to temporary obstruct sally ports. Because they took some effort to construct, chevaux-de-frise were only used when an army remained in location for an extended period of time.

The main line of works had several components, typically including a ditch on the enemy side; an earthen embankment or parapet that sheltered the defenders; a revetment, or retaining wall, on the inside of the embankment, against which defenders stood to fire their muskets; head logs, installed several inches above the revetment to protect soldiers’ heads as they fired; and traverses, or walls of log, timber and dirt extending 15 to 30 feet from the parapet back into the defenders’ line to prevent the enemy from enfilading the entire line.

A ditch, similar to a castle moat in principle, sometimes included obstructions like fraise (closely spaced, sharpened timbers driven into the earth and angled toward attackers), a palisade, or other obstructions. If the earthworks did not have a defenders’ trench, often an earthen platform called a banquette was built a few feet above the ground to allow defenders to fire downward on their foes. Similarly, an earthen platform—often reinforced with a timber floor—called a barbette was constructed for artillery.

Breastworks were arranged in straight lines runs called curtain walls, and commonly included redans, advanced works used to cover a sally port or defend a blockhouse along a railroad. Redans were usually not much more than a V-shaped breastwork, often with a ditch in front, with the point of the V facing the enemy and an open back, or gorge, to the rear. They were placed along the main line of works to permit the defenders to enfilade enemy troops that approached the curtain wall. While redans varied greatly in size, most were between 30 and 60 yards line. An inverted redan was called a tenaille. Lunettes were similar to redans, but instead of being V-shaped, they had two faces and two flanks.

Redoubts were polygonal, redan-type structures. Unlike redans, Federal redoubts were usually enclosed on all sides, and usually were larger than redans, including underground powder magazines and bombproofs to protect the garrison. Redoubts were local strong points, and famous forts such as Fort Stedman were, strictly speaking, redoubts.

Embrasures were trapezoidal-shaped openings in earthworks used by artillery. The artillery could be positioned as single pieces, as sections (two guns), or as four-to six-gun batteries. The ground immediately behind the works was termed the terreplein. If time allowed, an army sometimes constructed more than one main line of earthworks so that if the first line fell, the secondary defense could hold the line and serve as a launching point for counterattacks. Man-made and natural features were almost always incorporated into fieldworks, including high ground, marshes, watercourses, and buildings. Most army-sized fieldworks were securely anchored on impassable terrain features such as a wide river, large swamp, or steep ridge.

The main line of earthworks was not the initial line of defense. Out in front were rifle pits manned by vigilant pickets and their supports. Closer in, portions of the main line were preceded by obstructions, including natural barriers like streams and man-made defenses such as abatis, palisades, fraise, chevaux-de-frise, and horizontal “nets” of telegraph wire strung about 18 inches above the ground. In addition, there would be advanced works such as redans and lunettes. Indeed, an enemy had to pass a number of formidable defenses before reaching the main line of works.

The main line of works—ditch, breastworks, trenches, etc.—was typically located at or near the military crest or a rise in the terrain (the topographical crest or highest point was not where fieldworks were constructed), which allowed the defenders good sight-distance and the advantage of height to fire down on their attackers. The extent of fieldworks behind the main line depended on the terrain and on how long the army occupied the position. The areas behind the works could include additional lines of fieldworks, artillery emplacements on higher ground, zigzagging communications trenches to the main line, encampments, field hospitals, headquarters, and wagon train parks.

The complexity and use of fieldworks increased as the war progressed, and by late 1863 the opposing armies were doing more digging than shooting. However, some fieldworks were used throughout the war. Extensive, siege-type works were built near Washington, D.C., in 1862, at Yorktown, Va., in 1862, and Suffolk, Va., in early 1863. Natural fieldwork-like terrain features figured prominently in such battles as Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Bristoe Station.

To be sure, 1863 was a pivotal year for fieldworks in the eastern theater of the war. Federal troops constructed many slight to moderate works during the Chancellorsville campaign that May, and moderate works were built on Culp’s Hill, Little Round Top, and along Cemetery Ride at Gettysburg. By November of 1863, fairly extensive fieldworks were constructed during the Kelly’s Ford, Rappahannock Station and, Mine Run campaigns. In the spring of 1864, the Battle of the Wilderness saw extensive construction of moderate works, and following the Battle of Spotsylvania that May, the opposing armies of Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee perfected the art of fieldworks during the 10-month siege of Petersburg.

One problem for both armies was storm water drainage. In many Civil War fieldworks there was not a suitable location for drainage, as evidenced by a South Carolina defender of Spotsylvania’s Bloody Angle who recalled, “The trenches, dug on the inner side [of the works] were almost filled with water.” In fact, during very heavy rain, troops were sometimes driven out of their own works by rising water, such as occurred when some Confederate units abandoned their works at Cold Harbor during the night of June 2-3, 1864, making their line vulnerable to attacking Federal troops. Fortunately for the soldiers, much of the soil in the eastern theater of the war a clay-sand mix that usually drained fairly quickly.

When sited under fire, the first line of main works was usually excavated under the direction of field and line officers, or in dire situations by the men themselves, either in positions of military advantage such as the top of a rise in the ground, or simply where the advance halted. Typically, the soldiers constructing fieldworks would stack their muskets and form details for excavation and construction. While most of the manpower was used in earth-moving, other details cut down trees for revetments and head logs. Sometimes other handy materials such as fence rails and rocks were gathered and incorporated into the line, and old logs were often tossed in and made part of the embankments. The tops of trees used for revetments were cut off and used for agates. Other men cleared brush from the forward field of fire.

The entire process was neatly summarized by Union soldier Edward Tillinghast in a letter to his father in November 1863. “I will tell you how the breastworks are made,” Tillinghast wrote. “The first works will be made along the line of the regiment, usually short of the crest of a hill. Fence rails and stones are piled in front, and then we cover this with dirt which is loosened with bayonets and moved in our plates. All this is done in a twinkling. After a while the axes, spades, and picks will arrive, along with an officer who will usually make us move parts of the works to create embrasures &c. Last we will cut away the brush and trees in front of our works and lace them together to create a sort of hedge that is difficult to pass [abatis].”

Union Colonel Theodore Lyman wrote of the troops after Cold Harbor: “They are throwing up dirt as hard as they could. No country could be more favorable for such work. The soldiers easily throw up the dirt so dry and sandy with their tin plates, their hands, bits of board, or canteens split in two, when shovels are scarce; while a few axes, in experienced hands, soon serve to fell plenty of straight pines that are all ready to be set up, as the inner face of the breastworks.”

While a sturdy revetment was preferred, in an emergency almost any available material was used, as one Pennsylvanian, Daniel Chisholm, recalled during the Battle of the Wilderness: “We fell back to the road (100 yards) and commenced to pile up old rotten logs, dry brush, &c. We had no shovels and we had to dig with our bayonets and throw up direct with our hands. We worked all night, and then our works were poor.” Similarly, George K. Collins recalled the works at Culp’s Hill: “The men grumbled a little and said it was the old trade of building works never to be used; nevertheless they brought sticks, stones, and chunks of wood, and felled trees and shoveled dirt for three or four hours.”

Sometimes the contested ground was not conducive to fieldworks, and the soldiers made do with what was available. On the beaches off the Carolina coast, revetments to hold the sand in place were necessary. In elevated areas, brush and sod had to be removed to erect works. In some areas, ground was not readily “digable,” forcing the soldiers to look for other means of protection. Minnesotan James A. Wright recalled of the hard, rocky soil on Gettysburg’s Cemetery Ridge: “We gathered rails, stones, sticks, brush, &c., which we piled in front of us, and loosened the dirt with our bayonets and scooped it onto these with our tin plates and onto this we placed our knapsacks and blankets. Altogether it made a barricade from 18 inches to 2 feet high that would protect us from rifle bullets.”

Most soldier accounts reported that trench life was a miserable experience, with the men exposed to the sun, rain, thirst and privation—not to mention enemy fire. One unhappy Wisconsin soldier wrote of life in the trenches during the fight for Globe Tavern, near Petersburg: “Saturday 20th [of August 1864], in breastworks; sat around all day in rain and mud; everything soaking wet; no fires; no coffee; lived on condensed milk and hardtack. Sunday 21st, clear and bright; hung our blankets and things to dry.”

Sometimes the men managed small cooking fires in the works to boil coffee, but usually the soldiers reported being hungry in the forward trenches, where both cooking fires and hot food were rare. When not under direct enemy fire, the men went to the rear to relieve themselves. An irate Union soldier, Frank Wilkerson, recalled that at the North Anna River in May 1864, “There was an unwritten code of honor among the infantry that forbade the shooting of men while attending the imperative calls of nature, and these sharpshooting brutes were constantly violating that rule.” During times when a visit to the sinks would probably have meant injury or death, men simply relieved themselves in their own works—making a bad situation even worse.

When the opposing lines were in close proximity to one another, particularly in 1864-65, sniper fire made life in the trenches miserable. As one Confederate related at Cold Harbor in June 1864: “Sharpshooters [of the 7th New York Heavy Artillery] were so vigilant and expert at their business that a head could hardly show itself above our earthwork without getting a ball through it. A hat put on a ramrod and raised a little would be perforated in a jiffy.”

Entire regiments usually manned a line of works. Typically, entire brigades or larger units were kept as a reserve, and it was uncommon for a regiment to be split, with a portion in the line and the balance in reserve. However, it was common for a portion of a regiment to be on picket in front of the main line of works, with the rest manning the trenches.

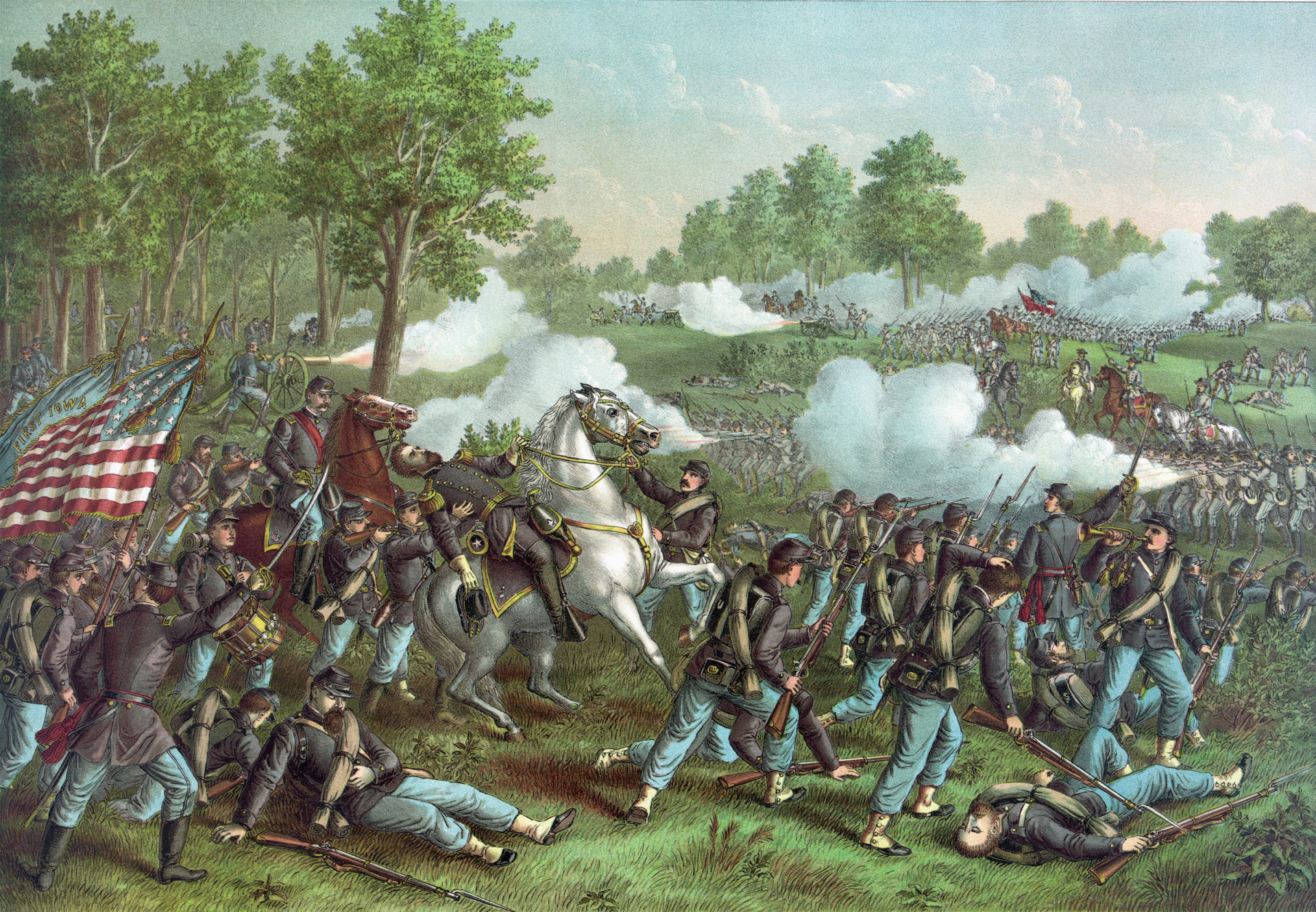

Fieldworks were defended with everything their occupants possessed. Officers would order the men massed in the works to fire when the enemy was well within range—typically at less than 300 yards. Musketry at that range was murderous, particularly later in the war. After an opening volley, most of the firing was at will, as fast as each defender could load and fire. If the enemy was able to reach the works and the defenders stood their ground, close-in combat took place with bayonets, clubbed muskets, and even fists. Because traverses were a common component of fieldworks, breakthroughs were often contained to a fairly small area.

Troops ordered to attack a fortified enemy line usually experienced strong feelings of trepidation—this was true both for “fresh fish” as well as veterans. A member of the 1st Minnesota wrote of the regiment’s dread the night before it was to assault the Confederate fieldworks at Mine Run in November 1863. “We could plainly see the line of earthworks on the crest of the gentle slope rising before us,” noted William Lochran. “We could hear the incessant sound of entrenching tools in the enemy’s works. We knew that it was expected that we should charge those works, and earnestly wished that the order would come to do so in the darkness, before they were made stronger and reinforced.”

Often, it appeared to the attackers that the enemy works were deserted—not a man could be seen in them as the assaulting force approached. But as soon as the enemy skirmishers disappeared back into their own lines, hundreds of flashes from enemy muskets became visible, followed by puffs of smoke and whizzing bullets. Troops attacking stoutly defended earthworks were often unable to reach them at all, and were pinned down in no-man’s-land until they were able to withdraw. Troops pinned down sought cover by any means possible, placing their knapsacks or blanket rolls in front of them, hiding behind cover—including dead bodies—and digging shallow rifle pits. If the assaulting columns were able to penetrate the enemy position, the resulting fighting was typically brutal and bloody. In the end, attacking Civil War fieldworks was almost always an extremely costly enterprise.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments