By Michale D. Hull

There was tight security and feverish activity on the dock at the Hunters Point Navy Shipyard in San Francisco Bay around 3 am on Monday, July 16, 1945.

Two U.S. Army trucks unloaded a precious cargo—a large crate and a two-foot-long metal cylinder containing a uranium projectile and components for the “Little Boy” bomb, destined to be dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima and usher in the atomic age.

Moored at the dock and making ready to get underway was the fast, heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35), commanded by 46-year-old Captain Charles B. McVay. As soon as a big gantry crane quickly lowered the cargo aboard the ship, the crate was secured to the deck and surrounded by a U.S. Marine guard, and the cylinder was placed in the flag lieutenant’s cabin.

Rear Admiral William R. Purnell, the naval member of the Manhattan Project’s Military Policy Committee, told McVay that if the ship ran into trouble the cylinder was to be saved at all costs. The ship would be carefully tracked during its voyage, and if anything happened to her, it would be known within hours.

It was a unique, top-secret assignment for the 13-year-old Indianapolis. Rushed to completion and commissioned on November 15, 1932, she and her sister ship, the USS Portland, were modifications of the Northampton-class cruisers. They were critically top heavy with new electronics, light antiaircraft weaponry, and fire control gear.

With a complement of 1,196 officers and sailors, the Indianapolis displaced 9,800 tons, was 610 feet long, and had a top speed of 32.5 knots. Her armament included nine 8-inch guns, eight 5-inch dual-purpose guns, and two 3-pounder guns. Though a “treaty cruiser” with some design deficiencies like others of the Northampton class, the Indianapolis was a proud member of the U.S. Fleet. She boasted a handsome teak quarterdeck before being stripped for war and had an enviable reputation for sharp ceremonies and honors performed by her Marine Corps detachment.

As a lifelong private sailor, former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, and fervent advocate of sea power, President Franklin D. Roosevelt held a special affinity for the Indianapolis. He watched seagoing maneuvers from her deck in May 1934 and sailed aboard her when he undertook his unprecedented “Good Neighbor Policy” cruise to Latin America in late November 1936.

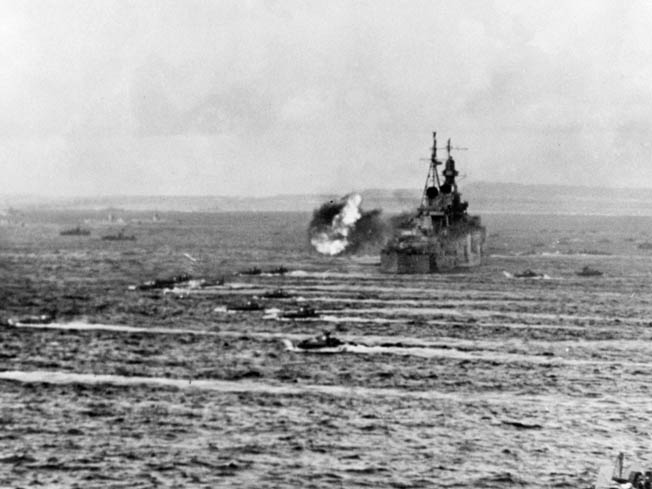

At 8 on the morning of July 16, 1945, the Indianapolis cast off, bound for the island of Tinian in the distant Marianas group. She steamed under the Golden Gate Bridge half an hour later and headed westward across the Pacific Ocean. Recently patched up at Mare Island, California, after being severely damaged by a Japanese kamikaze plane on March 31, 1945, during the Okinawa invasion, the cruiser was a veteran of more than three years of fleet duty. She had been with the Pacific Fleet from the time of the Pearl Harbor raid on December 7, 1941.

After taking part in early 1942 raids, she saw action in almost every major amphibious invasion in the Central Pacific and lent fire support in the Aleutians, Gilberts, Marshalls, Kwajalein, Eniwetok, Saipan, Guam, Palau, and Iwo Jima operations. The Indianapolis also served as the principal flagship of Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance when he commanded the Fifth Fleet.

Captain McVay, who ran a tight ship and was generally regarded as heading for higher flag rank, pushed his engine room crew to maintain top speed during the long voyage to the destination—the Twentieth Air Force’s Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bomber base on Tinian, three miles south of Saipan.

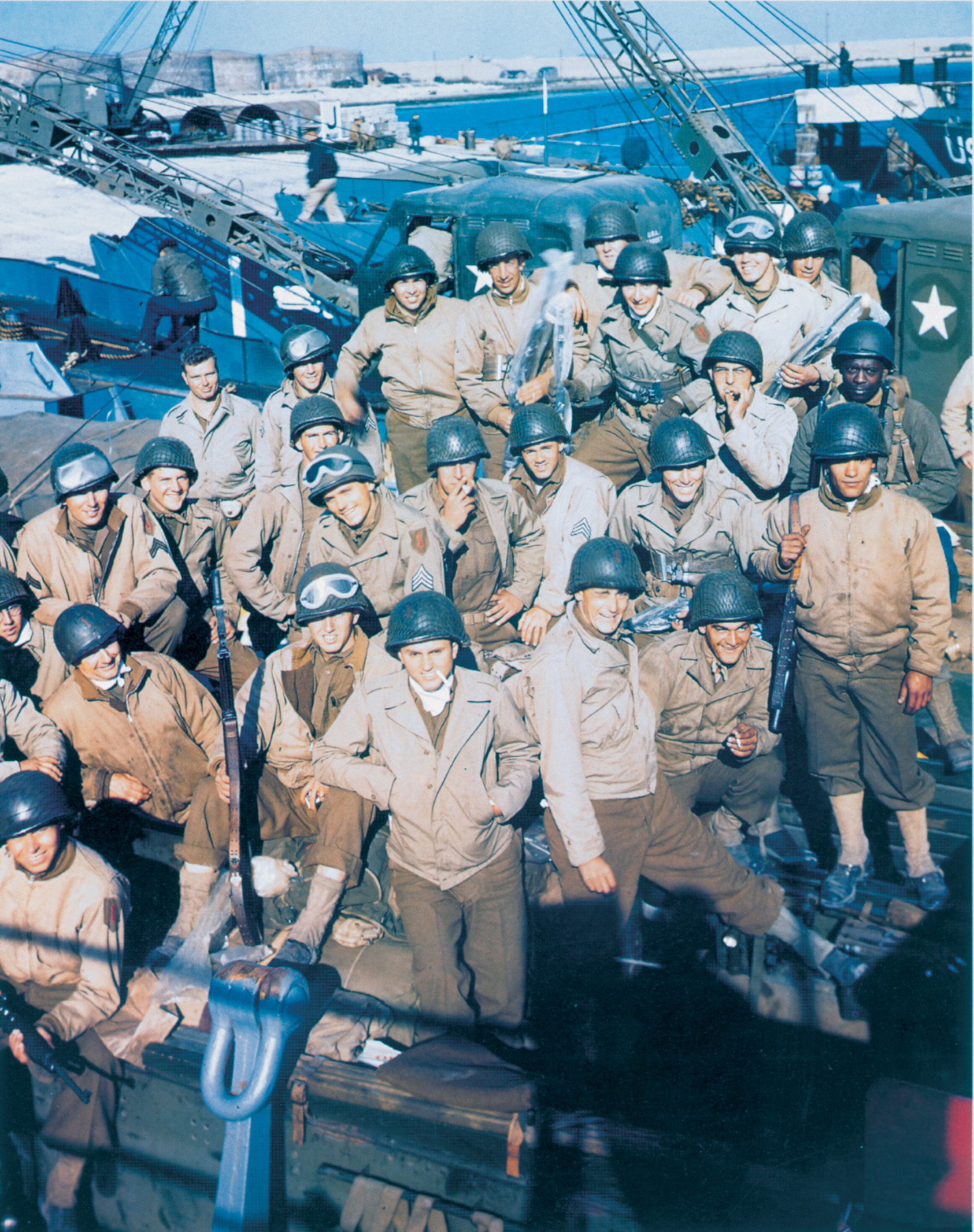

The cruiser reached the volcanic, 50-square-mile island shortly after daybreak on Thursday, July 26. Because Tinian did not have an adequate harbor, the Indianapolis dropped anchor 1,000 yards offshore. As small craft swarmed around the cruiser, high-ranking officers of all services climbed aboard to watch the unloading of the top secret cargo, the heart of the world’s first practical atomic bomb. A crane lifted the crate and cylinder into a waiting LCT (landing craft, tank), which promptly headed for shore. The cruiser had completed her unique mission, and McVay’s grave responsibility was over.

The cruiser then weighed anchor and steamed to Guam, the southernmost island in the Marianas, where McVay was briefed and given new orders. The Indianapolis was to head for Leyte Gulf in the Philippines for two weeks of training exercises before rejoining the fleet and preparing for the Allied invasion of the Japanese home islands. Unescorted, the cruiser departed from Guam on July 28 and proceeded westward.

McVay and his crew were unaware of the dire perils that lay ahead. “There was no mention made of any untoward incident in the area through which I was to pass,” he reported later. “I definitely got the idea … that it was a routine voyage.” A lieutenant and an ensign aboard the cruiser charted a direct, straight-line route at 15.7 knots estimated to get the ship into Leyte on July 31.

Surface and air units of the Imperial Japanese Navy had been rendered virtually impotent by late that month. In strikes against airfields, the naval base at Kure, and shipping in the Inland Sea, the powerful Task Force 38 of Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey’s U.S. Third Fleet sank or badly damaged numerous enemy vessels, including the battleships Haruna, Ise, and Hyuga; the carriers Amagi, Katsuragi, and Ryuho; the heavy cruiser Tone; and the cruisers Aoba and Oyoda.

The Americans had written off the Japanese fleet as a threat in rear areas, but it was not quite finished because a few of its submarines were still at large. A final offensive by six diesel-powered I-boats, each carrying six kaiten one-man midget submarines (human torpedoes) as well as conventional Long Lance torpedoes, was underway in the Western Pacific.

Early that month, U.S. intelligence experts had decoded Japanese messages and confirmed the presence of four enemy submarines in the main shipping lane to Leyte. On July 24, while shepherding a convoy from Okinawa to Leyte, the destroyer escort USS Underhill was crippled off Luzon by a kaiten from I-53 and then scuttled by submarine chasers. The death toll was 112 officers and men. But an Ultra intelligence intercept of a message from Lt. Cmdr. Mochitsura Hashimoto claiming that his I-58 had sunk an American battleship was dismissed as the usual Japanese exaggeration.

The Indianapolis sailed on across the Philippine Sea, but a series of errors and oversights was sealing her fate. She had no underwater detection equipment and was dependent on radar and eyesight to detect a submarine. Routing officers, meanwhile, had told McVay that he would not need an escort. The cruiser was on her own, and her whereabouts would be unknown for several critical days.

A headquarters radio message to the battleship USS Idaho in the Gulf of Leyte, reporting that the Indianapolis was on her way there, was incorrectly decoded and discarded. Next, a Navy radio relay station on Okinawa somehow lost a routing message to Leyte saying that the cruiser had left Guam. Leyte was unaware that the ship was coming.

Seven hours after the cruiser left Guam, the merchant ship SS Wild Hunter dispatched an urgent message from farther along the cruiser’s planned course, reporting that an enemy periscope had been sighted. The destroyer escort USS Albert Harris and reconnaissance planes investigated but reported losing contact with the submarine.

Steaming to an area northeast of Leyte, the Indianapolis zigzagged to make tracking by enemy forces more difficult, although the maneuver was not required in presumably safe waters. Standard fleet instructions required ships to zigzag only when the visibility was good. Captain McVay’s routing orders directed him to zigzag “at discretion,” which he did by day. The cruiser had no lifeboats and only a few life rafts, but the end of the Pacific War was in sight. The Japanese Navy was no longer seen as a threat, and there was no reason to believe that the voyage to Leyte was anything but a routine assignment.

At twilight on Sunday, July 29, the visibility worsened under cloudy skies and the sea became choppy, so Captain McVay ordered a halt to the zigzagging. The ship resumed a straight, steady course. At 11 pm, after going to the bridge to check on the night watch, he went down to his cabin to sleep.

The Indianapolis was not “buttoned up” above the second deck. Like the Navy’s other aging heavy cruisers, she had no air conditioning to make sleep possible for the crew in tropical waters, so the skipper allowed all ventilation ducts and most bulkheads to remain open. The entire main deck, the doors on the second deck, and the hatches to living spaces below were all open.

At the same time that Captain McVay turned in that night, Commander Hashimoto awoke from a nap aboard his I-58. Believed to be the fastest and best equipped submarine in the world, she carried six big oxygen-powered kaiten torpedoes, each with a 3,200-pound warhead. These were lashed on deck and designed to be piloted by one-man crews on suicide missions. I-58 also carried conventional Long Lance torpedoes below decks.

The submarine’s radar operator suddenly spotted a blip on his screen, and the crew sprang into action. Hashimoto submerged to periscope depth, and I-58 closed in on the target, which proved to be the USS Indianapolis. Because she lacked sonar gear, the cruiser had no inkling of the enemy submarine’s presence.

Although he had been running kaiten missions for several months, Hashimoto decided to attack with conventional torpedoes this time. I-58 closed to a distance of 1,648 yards from the target at 12:05 am on Monday, July 30, 1945, and fired six Long Lances at the unsuspecting American ship.

Two and possibly three of the torpedoes slammed into the underwater starboard side of the Indianapolis. The first smashed into the bow, starting a huge fire below decks, and three seconds later the second torpedo found its mark directly below the bridge and detonated. The cruiser was soon burning fiercely.

Although the after half of the ship was untouched, the torpedoes set off a series of violent ammunition and fuel explosions, which blew off her bow. Tons of water gushed into the forward part of the cruiser, and her engines drove her under as she listed at an angle of 45 degrees. Spruance’s gallant flagship was doomed.

From amidships forward, there was no power, light, or pressure. Because the communications and most electrical lines had been severed, the bridge was unable to order the engines stopped, and the engineers could not stop them on their own. Captain McVay was unable to broadcast or sound orders. There was auxiliary power in the radio room, according to survivors’ reports, and SOS and position messages were sent out by the stricken cruiser. But none were apparently received, possibly because of antenna damage.

Eight minutes after the first torpedo struck, McVay gave verbal orders to abandon ship. But below decks hundreds of crewmen who had been sleeping were trapped, mortally wounded, burned, or drowned. Between 350 and 400 men went down with the ship. Of the estimated 800 sailors who were able to jump into the oilcoated sea, many were also wounded or badly burned and drowned.

The Indianapolis went down in 12 minutes. She was the last American warship to be sunk in World War II, the last submarine kill, and the last victim of the Imperial Japanese Navy. It was the most controversial disaster in U.S. naval history. Her skipper was one of the few survivors, but the tragedy was to prove his downfall.

A harrowing ordeal awaited the men able to clamber into the life rafts. They suffered four days of agony while the Navy had no knowledge of the cruiser’s fate. Huddling in the life rafts or floating in lifejackets, the survivors drifted under a blistering sun while salt water caked and aggravated wounds. The fresh water aboard the rafts was found to be contaminated, and there was little food.

Some of the men became violently sick after drinking seawater, and others went mad and attacked their comrades in the water. Many of the men in lifejackets were devoured by prowling sharks. Almost 500 sailors died while awaiting rescue.

While no one ashore in the Philippines noticed that the Indianapolis was overdue, the desperate men in the water prayed and waited—helpless and forgotten. An Army plane called in a report of flares being fired from the water, but it was ignored.

It was not until 84 hours after the ship had gone down that anyone learned of her fate. On August 2, the crew of a Navy patrol bomber on a routine mission from the Palau Islands accidentally spotted bodies in lifejackets strewn over a mile-long area. A rescue effort was swiftly mounted, and when ships and planes arrived on the scene in force the following day only 316 survivors were found out of the cruiser’s complement. Many of them were in shock from hours of exposure and having seen their comrades fall victim to sharks.

Suffering from exposure and dehydration, the survivors were rushed in rescue vessels to Peleliu. They were then transferred to the hospital ship USS Tranquility, which landed them in Guam on August 8. Admiral Spruance went to the hospital to visit his former shipmates and award Purple Hearts. “You’ll never know how happy I am to see you made it,” said the quiet, unassuming Battle of Midway victor, “and I’m only sorry we had to lose so many men I had come to think of as my family.”

News of the loss of the Indianapolis, a final blow struck by Japan, was withheld from the American public for 16 days. Then it went largely unnoticed as headlines blared the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the subsequent Japanese surrender. Distinguished naval historian Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison later called the Indianapolis tragedy a “tale of routine stupidity and unnecessary suffering.”

Major General Leslie R. Groves, the hard-bitten military commander of the Manhattan Project, said, “The Indianapolis was a very poor choice to carry the bomb. She had no underwater sound equipment, and was so designed that a single torpedo (sic) was able to sink her quickly.”

A Navy court of inquiry was convened in August and recommended that Captain McVay be court-martialed on charges of “culpable inefficiency in the performance of his duty” and “negligently endangering the lives of others.” He was to be the first U.S. Navy officer in more than a century to be tried for losing his ship to enemy action.

When the court-martial began on December 3, 1945, McVay was charged with “hazarding the safety of his ship by neglecting to zigzag in good visibility through an area in which enemy submarines might be encountered,” and the “failure to abandon ship in time, causing the death of many persons.”

McVay was acquitted on the latter count but found guilty of the former. The court-martial took the unprecedented step of summoning Hashimoto to testify that McVay was not zigzagging at the time of the torpedo attack. But the Japanese submarine commander said that he could have hit the cruiser, whether she was zigzagging or not.

Appeals for leniency for McVay were registered by several high-ranking naval officers, including Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the revered commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet. As an ensign, he had served briefly aboard the Indianapolis after graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy.

When Nimitz replaced Admiral Ernest J. King as Chief of Naval Operations on December 15, 1945, the court-martial was underway. He and the other officers advised strongly against it, but Navy Secretary James V. Forrestal had felt obliged to sanction it to quiet the press and satisfy the families of the men who were lost. Four other officers, meanwhile, received letters of reprimand in connection with the Indianapolis tragedy. They were the acting commander of the Philippine Sea Frontier, his operations officer, the acting port director at Leyte, and his operations officer.

At a press conference in his Navy Building office in Washington, D.C., on the morning of February 23, 1946, Admiral Nimitz briefed reporters on the court-martial findings. He stated, “We have no desire or intention to deny any of our mistakes.” He said that the court-martial members and the judge advocate had recommended clemency for McVay and that this was supported by senior officers familiar with his service record.

Nimitz added that Secretary Forrestal “has approved these recommendations and has remitted the sentence of Captain McVay in its entirety, releasing him from arrest and restoring him to duty.” A newsman asked the admiral, “Has there ever been a court-martialed officer in the history of the U.S. Navy who was later promoted to flag rank?”

Grinning and with a twinkle in his blue eyes, Nimitz pointed to himself and replied, “Here’s one.” Much to the amusement of the reporters, he recounted how on the dark night of July 7, 1908, he had grounded the four-stack destroyer USS Decatur on a mud bank while entering Batangas Harbor in the Philippines. He was court-martialed, but because of his flawless record received only a reprimand.

With the exoneration of Captain McVay, press attention turned to the four reprimanded port officers as likely scapegoats in the Indianapolis case. But this was not justified when it was established that they were merely following orders. For security reasons, port directors had been instructed not to report the arrivals of warships. It was further shown that when the ill-fated cruiser failed to arrive at Leyte the port director assumed that she had been delayed at Guam or diverted to another command. After a close study, Forrestal withdrew the four letters of reprimand.

McVay had been exonerated, but the tragedy sidelined his career. He was assigned to a minor post in New Orleans and marked time for three years until retiring from the Navy on June 30, 1949, at the age of 51. He left with the rank of rear admiral.

Despondent, he retired to Litchfield, Connecticut. On November 6, 1968, he went for a stroll on the lawn of his home with his pet Labrador retriever. He was later found shot through the head, with a .38-caliber pistol in his right hand and a blue toy sailor grasped in his left.

Author Michael D. Hull is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He writes on a variety of subjects and resides in Enfield, Connecticut.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments