By Jon Diamond

The iconic photograph the Blinded Soldier, New Guinea taken on Christmas Day 1942, reveals a wounded and barefoot Australian soldier, Private George “Dick” Whittington of the 2/10th Battalion, being led down a path through a surrounding field of tall kunai grass to an Allied field hospital at Dobodura in Papua, the eastern third of the world’s second largest island, New Guinea.

Whittington is assisted by a native Papuan, a Good Samaritan or “fuzzy-wuzzy angel” named Raphael Oimbari. The photographer, George Silk, created an indelible image of the Allied struggle to retake Papua’s northern coast from the Japanese from November 1942 to January 1943. The Australian private had been wounded in the ferocious fighting for the airstrip near Buna the day before. The photograph was disseminated worldwide as Life magazine’s “Picture of the Month,” and thus informed the civilians back home about the horrific combat conditions in General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Theater.

The photographer of the Blinded Soldier, New Guinea, George Silk, recalled at a later time, “As I remember that incident it was Christmas Day and I had been back at the Battalion Headquarters … and I was making my way up to the front … only a few hundred yards away, across this field of tall kunai grass … I was the only person on the path and suddenly I saw these two people walking towards me … This native is helping this man so tenderly … I thought I’ve got to take a picture! But I sort of didn’t want to. I didn’t want to interfere … and as I remember I took one shot.”

Ironically, Silk’s photograph did not initially appear in Australia, where he was employed by the Australian Department of Information as a combat photographer. Perhaps, for morale or other reasons, the Department of Information had suppressed the publication of Silk’s image in Australia for almost two months. Parenthetically, Whittington recovered from his wounds incurred on December 24, 1942, but died of scrub typhus at Port Moresby on February 12, 1943. Oimbari, of the Papuan Koiari tribe, received the Order of the British Empire for his wartime assistance to Australian soldiers, and he became the international face of the Papuans, who helped the Allies immensely in the combat supply and evacuation of wounded during the early campaign on New Guinea.

Just weeks earlier, while near a dressing station at Gona, another Japanese stronghold on Papua’s northern coast which before the war was an Anglican Mission, Silk witnessed an Australian soldier pick up a wounded Japanese prisoner and carry him on his back to the aid station. Silk was moved by this scene of the Australian soldier overcoming his bitterness and acting as a Good Samaritan, too. While photographing the prisoners at the aid station, Silk said, “I must get this, this is good propaganda … Not many Japs surrendered … if they were in good shape they would kill themselves…. The ones that were captured were mainly Korean workmen.”

Moving to the European Theater, Silk took a series of close-sequence images to emphasize the drama of February 23, 1945, when American combat engineers attached to the U.S. 102nd Infantry Division on the east bank of the Roer River near the German town of Jülich captured Germans left behind who were sniping at them while a pontoon bridge was being constructed. When two of the engineers herded the three prisoners back to the pontoon bridge, one of the Germans pulled a live grenade out of his pocket and tossed it to the ground.

The German who threw the grenade died, while the other two captured enemy soldiers were badly wounded by the shrapnel. The two escorting American engineers were only dazed; however, George Silk, suffered a leg wound from the shrapnel. On March 12, 1945, Silk’s close sequence of still photographs memorializing this event was published by Life, his employer since early 1943. At that time, Silk’s idea of combat photography was to be out ahead of infantrymen crossing a German river under fire.

Silk’s photographs became some of the most celebrated images of World War II. Always close to the combat to capture these exquisite images of the internecine conflict between unwavering enemies either in Papua’s miserable terrain, which Allied veterans referred to as a “ghastly nightmare,” or across the frigid plains and waterways of northern Germany, Silk once said, “The camera is part of you, it’s your skin! Emotions are powerful, they hit hard, they wash over you. They can’t overwhelm you, you’re doing a job…. Sometimes it was an emotion that took the picture.”

Silk had a strong attachment to his vocation, believing that he “was going to save the world by [his] photographs.” Colleagues commented that Silk wanted to be amid the combat action “and conquer his fears and show people what it was like.” He was not immune to the horrors of war, as was evidenced by his collapse with malaria at Buna and his shrapnel wound in Germany.

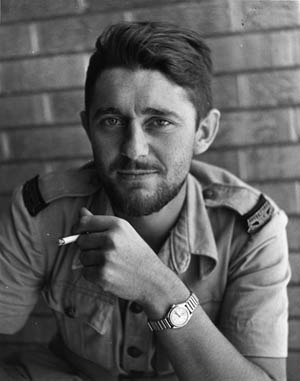

George Silk was born on November 17, 1916, in Levin, New Zealand, and educated at Auckland Grammar. Tinkering with cameras from a young age, he began working in a camera shop at age 16. When the war began in 1939, he was hired as a combat photographer for the Australian Ministry of Information after showing some sports pictures that he had taken as a clerk in the camera shop.

His assignment was to follow the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) formations throughout North Africa, the Levant, and Greece, along with his close colleague Damien Parer, who was later killed in action. Both were to become the best of the AIF photographers and among the finest of World War II. Parer was primarily a movie cameraman, while Silk created still photographs. Both understood the importance of sequential images. In Libya, trapped with the Australian “Desert Rats” of Tobruk, Silk was captured by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s forces. However, he somehow managed to escape 10 days later.

The Japanese landed on Papua’s northern shore at Buna and Gona in July 1942 and drove overland to Port Moresby on the southern shore of New Guinea across the formidable Owen Stanley Range to threaten northern Australia. As Australian militiamen, followed by veteran AIF formations returning from the Middle East, drove back up the Kokoda Trail following the retreating Japanese toward their northern coastal staging areas from late September to November 1942, Silk was soon to become immersed in the hellacious combat that the “Diggers,” as well as the relatively inexperienced National Guardsmen of the U.S. 32nd Infantry Division, would face against the camouflaged bunker system that housed tenacious Japanese Army infantrymen and Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) troops at Buna and Gona under the command of Lt. Gen. Hatazo Adachi.

The Bushido code forbade the Japanese soldier to surrender. Thus, Silk photographed the suicidal combat the enemy soldiers inflicted on Australian infantrymen, first at the Anglican Mission site of Gona, and then on both American and Australian infantry and Australian-crewed M3 Stuart light tanks at Buna. Places along the Buna front with names such as the Duropa Plantation, Old and New Strips, Giropa, and Strip Points, would become forever immortalized for the valor and sheer carnage captured by Silk.

The great photographer used a Contax camera with a telephoto lens as well as a Rolleiflex camera. Both devices enabled Silk to follow the action in Papua and capture close-up images of the Diggers in candid settings. Remembering his journey from Port Moresby to the Buna-Gona front in early November 1942, Silk commented, “By the time I got up there the Australians had pushed across the top of the ranges and were about to take over Kokoda Strip. The Army told me to wait and within a couple of days I’d be able to fly into Kokoda….”

During the December 18, 1942, attack in the eastern sector of the Buna front by elements of the 18th Australian Infantry Brigade, Silk photographed some of the fiercest close combat of the war as the Aussies advanced into the Duropa Plantation and Cape Endaiadere, ground that the U.S. 32nd Division failed to capture with two infantry regiments. A big difference was that the Australians had a squadron of M3 light tanks, which pinned down Japanese machine gunners in their pillboxes with their 37mm gunfire.

Silk recalled, “I was ahead of the troops before the fighting started…. I was in front of the start line. I was running with my Rolleiflex and taking pictures…. Thank God I changed the film.”

The fighting was grueling even for an unarmed combat photographer. Silk reflected, “After I did Cape Endaiadere, and the mass of [Australian] casualties, and I came out of there pretty shot up emotionally and everything else, I took off a couple of days at battalion headquarters or regimental headquarters, and then I went back into the fighting at Giropa Point.”

On New Year’s Day 1943, George Silk recorded the intense Australian advance through tall kunai grass and palm trees to clear Japanese pillboxes and snipers at Giropa Point before the final attack on Buna Mission (also called Government Station). The assault was made by D Company, 2/12th Battalion along with the M3 tanks of 7 Troop, B Squadron, 2/6th Armoured Regiment.

While Silk took a succession of still photographs, the Australians suffered 80-90 casualties before the leading element of the battalion captured the Government Plantation southeast of Buna Mission. Silk was behind one of the M3 tanks taking pictures of the Australian advance through the tall grass and coconut tree rows.

He remembered, “It’s a pretty busy scene! Someone’s just been hit here; someone’s been hit there; and here’s another guy behind a tank shooting…. I mean I was very much aware that this was an amazing position to be in, where you could stand up and take pictures and not get immediately shot! I expected to be shot, because, look what’s going on!”

In another instance, a Vickers machine gunner, who just had one of his crew hit by a Japanese sniper in a coconut tree, yelled at Silk as he spotted him with a camera, “What the hell are you doing?… Get down, you bloody fool. They’ve just got my cobber!”

Late on New Year’s Day, Silk’s photographing of the fighting at Buna ended as he collapsed from exhaustion and was evacuated to Australia suffering from malaria. Silk recalled after the fighting at Giropa Point near the Government Plantation, “I turned around and wanted to go back. I’d had enough. I only went for a short distance and I passed out.”

During his convalescence, Silk learned that the publication of his still photographs had been suppressed by Australia’s Department of Information, his employer. Also, his photograph of a Vickers machine-gun crew with the limp body of a “cobber,” an Australian soldier with his extended arm lying next to the gunner, was censored.

Silk was bitter. “Here I was risking my life to do the job … that they accepted me for … and here they wouldn’t release the pictures!” The Australian government feared the repercussions from the families of killed and wounded soldiers seeing graphic photos depicting dead and wounded soldiers.

Silk was able to get the Christmas Day photograph of the Blinded Soldier, New Guinea passed by American censors, so it appeared in Life; however, the uncensored version of the dead Vickers machine-gun crewman remained suppressed by the Australian Department of Information. Nonetheless, the Life publication put Silk in an uneasy situation with the Australian government.

Silk commented, “And so I was up for treason from then on and I managed to escape from that, because by that stage of the game, I had all the newspapers on my side.”

Amid the bureaucratic turmoil and suffering from malaria, Silk left Australia’s Department of Information and joined Life to photograph the war in the European Theater. Australia’s Department of Information attempted to compel Silk to remain with his position using the “Manpower Act.” However, Silk was a New Zealand citizen, not Australian.

Additionally, many Australian newspaper editors supported Silk in his departure. His still photographs of the frontline combat and candid images of the Australian fighting men at both Buna and Gona were eventually published by a Sydney company (F.H. Johnson) with the title War in New Guinea: Official War Photographs of the Battle for Australia, in mid-1943. The publication included the attribution “Photographs by the Department of Information Commonwealth of Australia.”

Interestingly, Silk’s Blinded Soldier, New Guinea was the first image in the book, and it occupied an entire page. After joining Life, Silk never photographed Australians in combat again, and he continued to work for the American weekly periodical until it ceased publication in 1972.

Immediately after the war, Silk commandeered a Boeing B-29 bomber to take aerial photographs of a devastated Japan, including the first pictures of atomic bomb-stricken Nagasaki. He also photographed Japanese officers awaiting their war crimes trial in postwar Tokyo. In 1946, he shot an essay on famine in China’s Hunnan Province. The following year, he became a U.S. citizen. In America, the National Press Photographers Association applauded his work and recognized him as the “Magazine Photographer of the Year” on four different occasions.

For the rest of his career, Silk worked primarily as a sports photographer, recapturing some of his New Zealand outdoors upbringing. In his obituary, published in the New York Times on October 28, 2004, Margalit Fox wrote, “Mr. Silk was fascinated by motion, and sought innovative ways to snare its rush in a photograph…. Mr. Silk adapted a racetrack’s photo-finish camera [the strip or slit camera] to catch the fluid blur of an athlete in motion… Motion, Mr. Silk found, lay in the distortion.”

Silk also searched for “inaccessible spots” and developed methods in which he would separate himself from his camera to enable the photographs to be taken from almost impossible angles or vantage points such as the surface of a ski or the end of a surfboard.

In 2000, the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra put on a solo retrospective of his work titled “Going to Extremes.” Further exemplifying the exhibit’s title, Silk was the sole survivor of a glider crash in southern France during World War II. Also, he was the only photographer with a U.S. Air Force expedition setting up a weather station near the North Pole, where he risked -60 degrees Farenheit temperatures to capture a photograph.

For baseball fans, Smithsonian magazine’s Michael Shapiro in 2002 reminded us that it was George Silk, atop the University of Pittsburgh’s Cathedral of Learning, who took the photograph of Pittsburgh Pirate Bill Mazeroski at Forbes Field hitting New York Yankee pitcher Ralph Terry’s second pitch for a home run in the seventh and deciding game of the 1960 World Series in the bottom of the ninth inning when the game was tied.

That photograph, like so many others, was published in Life and remains an iconic baseball memorabilia poster to this day. Ironically, Silk claimed to not like crowds. For this former combat photographer who had once said, “I liked being a participant in things I photographed,” it was somewhat paradoxical for him to state, “I hated stadiums and I couldn’t work with all that noise in my ears.”

Perhaps it was the ghostly echoes of Buna, Gona, and all of those other combat zones that had become deafening to him.

Silk was once asked why he deliberately risked his life in the worst of combat. He answered, “I saw the soldiers fighting and dying and I was not fighting, but a civilian and drawing a captain’s pay. I was ashamed. So I drove myself to show the folks at home, as best I could, how the soldiers lived and died. I reasoned that I might do some good for humanity; that perhaps, if people got a good, rough look at how wars are fought, they might stop future wars—or something like that.”

Fortunately for George Silk, he died “an old man’s death” from congestive heart failure at the age of 87, in Norwalk, Connecticut.

Jon Diamond practices medicine in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and is a frequent contributor to WWII History. His Stackpole Military Photo Series book, New Guinea: The Allied Jungle Campaign in World War II, was released in June 2015.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments