By Robert Whiter

The short, slim man strove to keep still despite the stifling heat and the perspiration trickling down his face and neck. Clad in an army uniform he wasn’t used to wearing, he felt his sun helmet was more like a heavy iron band around his head. Nevertheless, his eyes absorbed all of the spectacle that was unfolding before him.

This was the Delhi-Durbar, December 12, 1911: King George V and Queen Mary were being made King-Emperor and Queen-Empress of India. All the worldwide newspapers and magazines would be needing graphic coverage of the great event—their readers demanded it. Photographers weren’t permitted to get too close. Even artists, then the main source for recording historical happenings, weren’t allowed too much leeway in carrying out their craft—they had to keep their distance.

For Fortunino Matania, graphic artist for the Sphere, a famous first-class British magazine, this wasn’t good enough. He had roughed out the basic essentials at dress rehearsals, but now he wanted all the important details, not only of their majesties’ regalia, but also of the attending officers and retainers and of the surrounding splendor. The different uniforms and dress of the various regiments also had to be noted and stored in his astounding photographic memory until such time as he would be able to commit it all to his drawing board and finish the complete picture.

A little bribe here and a spot of persuasion there, knowing the right people and, lo and behold, here he was in the front rank, in the uniform of a soldier, standing at the foot of the steps leading up to the throned dais. That his masquerade paid off was proved by the fact that his illustrations were in the editorial office of the London Sphere only 14 days after the event.

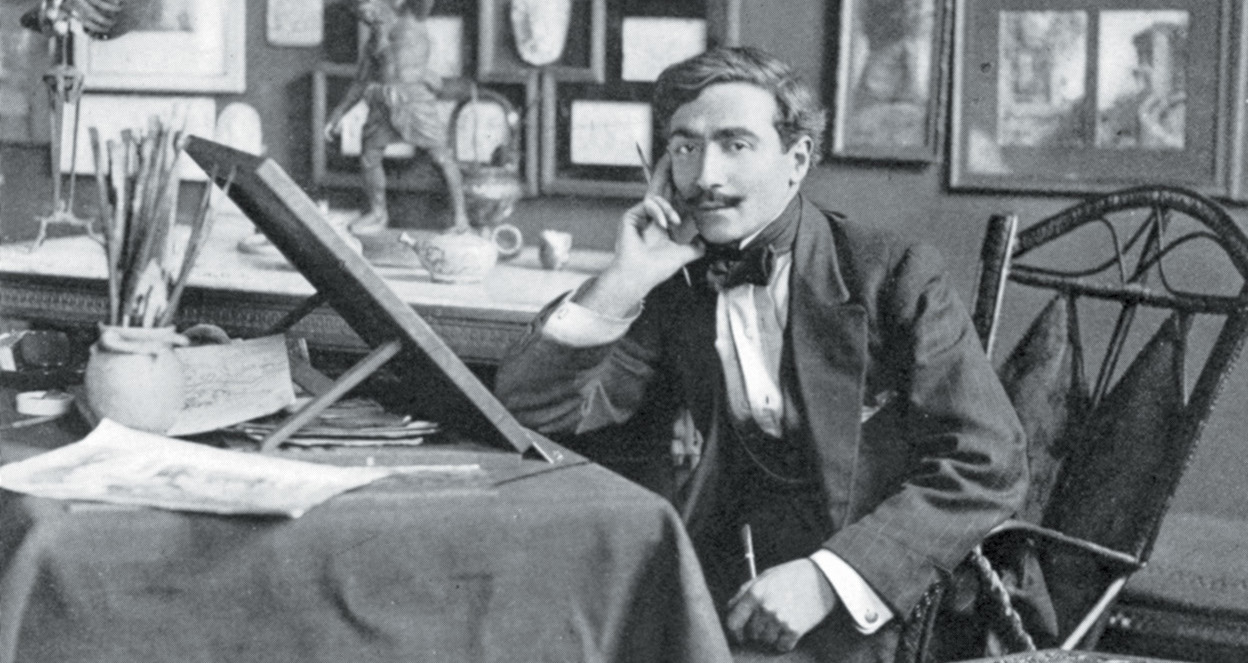

Fortunino Matania was born in Naples, Italy, in 1881, the son of Professor Cavaliere Eduardo Matania and Clelia della Valle. His father, a famous southern Italian artist, was a frequent contributor to several of the top Italian magazines, including the much-bespoken L’Illustrazione Italian. In later years, some of his work, together with that of Fortunino’s cousin, M. Ugo, could also be seen in the Sphere. A child prodigy, Fortunino had his first work published when only six years old. At age 11, his painting of a group of life-sized chickens was accepted by the Naples Academy.

The early years helping at his father’s studio certainly stood him in good stead. But when the editors in Milan began to receive drawings signed Fortunino Matania, they couldn’t believe that a 14-year-old boy was responsible. It wasn’t until the teenager rather shyly walked into their office armed with paper and pencil and executed a skillful drawing on the spot that they realized the truth. He was hired immediately. Even so, for quite a time when covering news stories, he had trouble convincing the officials that he hadn’t borrowed his father’s press card.

Very soon his work was noticed abroad and, in 1902, Fleet Street’s prodigious magazine the Graphic invited him to cover the Coronation of Edward VII. They couldn’t believe their eyes when the 19-year-old artist walked into their editorial offices. He spent three years with the Graphic before moving on to the Sphere, where in no time at all he became their principal artist.

In those days, being an artist for any of the leading magazines was no bed of roses. Often he would have to travel from one end of the country to the other just to cover some special event. In most cases, this would barely leave enough time to finish the drawings and get them to the engravers—the drawings had to be hand-engraved onto wooden blocks for reproduction.

To quote Matania himself, “The difficulty was to combine speed and finish. When we drew some official function, every portrait had to be recognizable in the finished illustration, every uniform perfect, every decoration correct. If we could publish within a week of an event, it was a feather in our caps.”

Having settled down comfortably in the United Kingdom, his tenure with the Sphere was broken only when he had to return to Italy to complete his military obligations (in an elite Bersaglieri unit). Discharged, Matania returned to the Sphere. Although he had by this time developed a great love for his adopted country, he never renounced his Italian citizenship. That proved no handicap until World War II when Italy declared war on Britain and France. However, with the help of friends, he was able to convince the British authorities of his loyalty to “Old Albion” and was not treated as an undesirable alien.

His marriage to Alvira du Gennario in 1905 gave him a son and a daughter (the union lasting until his wife’s death in 1952).

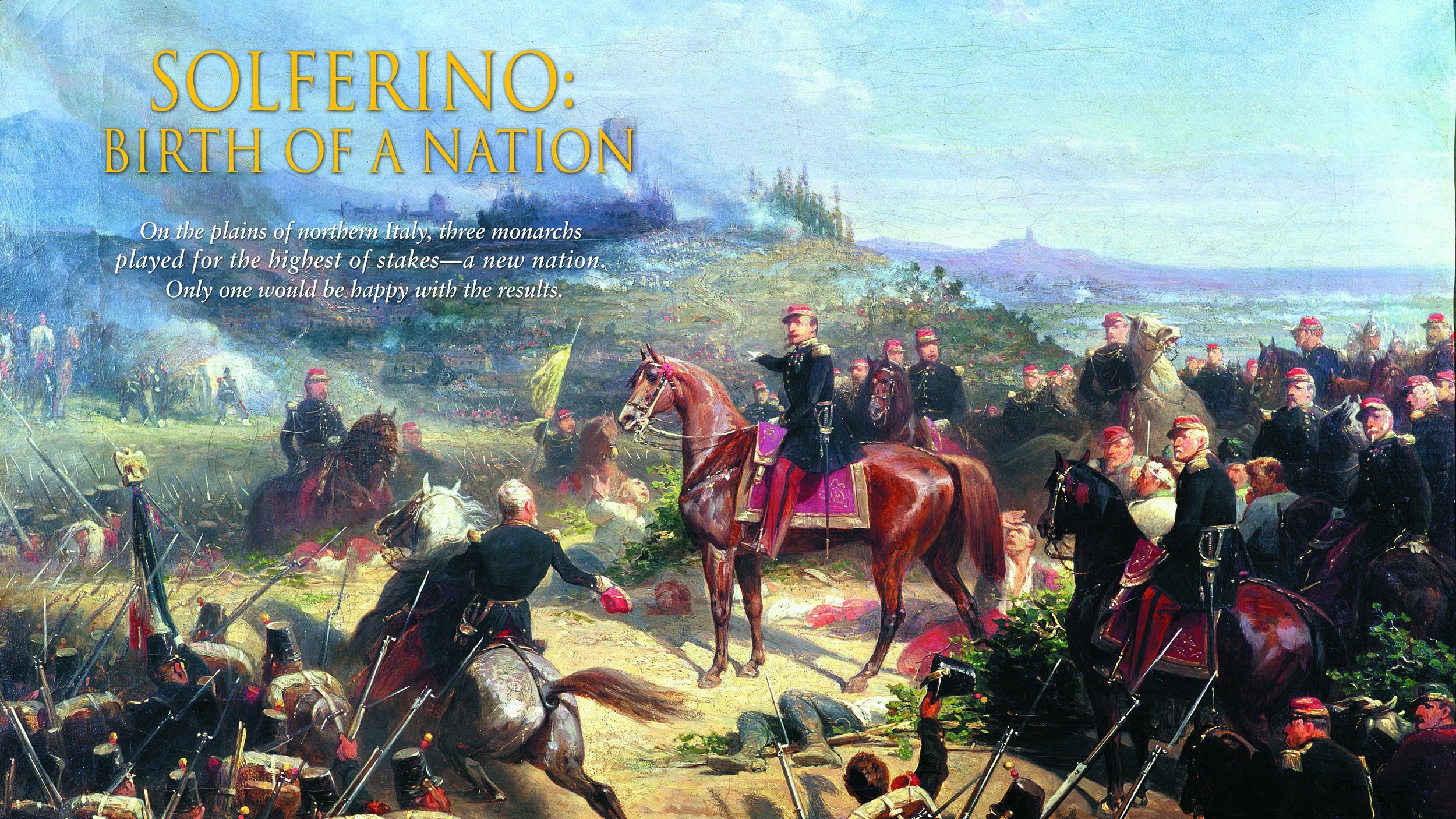

By the time World War I broke out in 1914, Matania had gained a great reputation and was much in demand. His attention to detail and the almost photographic quality of his work, particularly in his rendering of the 1915 Battle of Neuve Chappelle, was widely commended. He visited the front on numerous occasions, not only for the Sphere, but also on assignment for the Ministry of Propaganda.

If called on to hastily illustrate a certain incident or battle in the war but unable to cross the Channel for one reason or another, Matania would visit the hospital and chat with patients wounded in the engagement. If verbal questions could not elicit the answers and the information he needed, Matania would bring out a box of model soldiers and ask the patient to place them roughly in the positions both the British and the enemy had occupied. If buildings generally in a semiruined state were to be included in the picture, he would display examples of diverse styles of architecture. Even so, he would often revert to questions such as, “What sort of windows, what was the front door like, were there pillars on each side?” And so on.

In 1916, Percy Bradshaw, principal of a London correspondence art college called Press Art School, embarked on an enterprising scheme. Taking 20 well-known artists, he got each of them to start a picture and then stopped them about five times, photographing each phase of the illustration. The finished collection was called “The Art of the Illustrator,” and I feel fortunate to own a complete set.

Matania was third in the series and his “F. Matania and his work” is an education in itself. His finished picture, entitled “A Belgian Barricade,” is really a contradiction of all the laws of art. The Belgian soldier in the foreground, an awkwardly positioned figure to start with, was finished completely before making sure it would connect satisfactorily with the German Uhlan, while the drawing of the dog was started with the tail! The artist carried out all of this with Bradshaw watching and talking.

During the 1950s, I belonged to The Arms & Armor Society, of which Howard L. Blackmore was president. We were privileged to also have as members several editors of various magazines, including Look and Learn. I remember how proudly the good man of the latter displayed several original pictures that Matania had painted for him to accompany articles in this magazine. “Look at these. At his age he can still turn them out!” he would exclaim triumphantly.

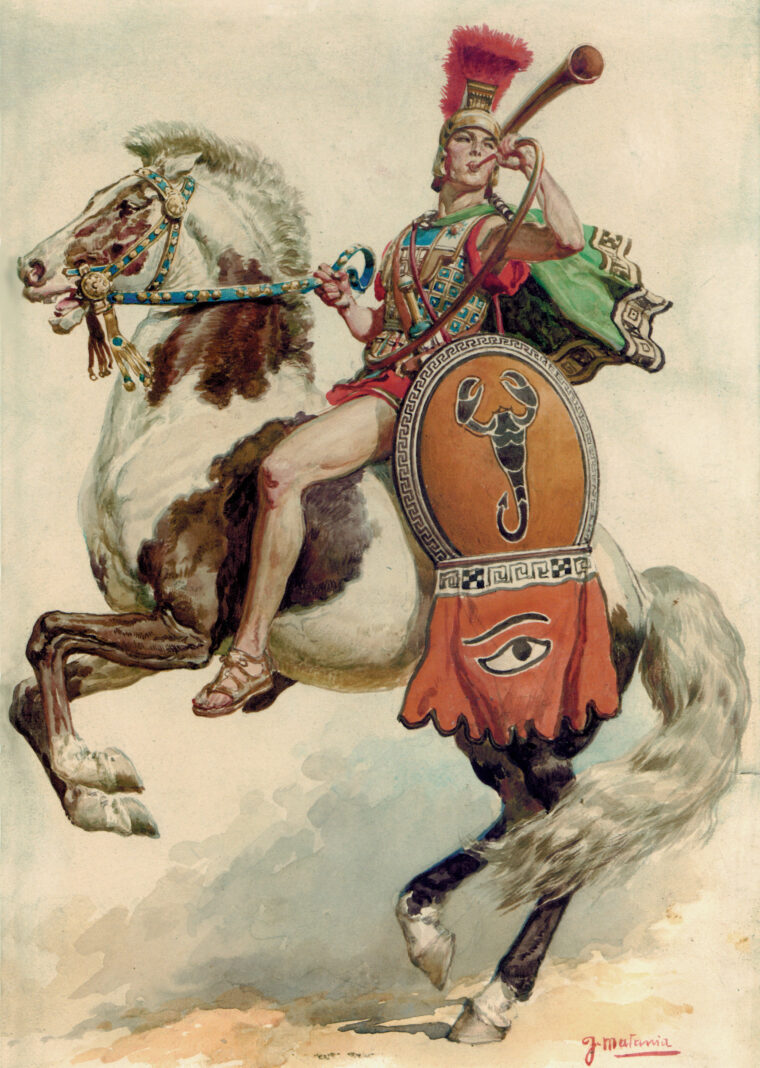

Knowing my own admiration for Matania’s work, he arranged for me to meet the artist at his office. At the last moment something cropped up and I couldn’t make it—I was mortified. They sensed how disappointed I was, and so a short time later presented me with a splendid watercolor of a Roman equestrian trumpeter. It has remained one of my most treasured possessions.

Matania was a consummate craftsman. Should an item such as a special piece of furniture be needed in a picture he was painting, and he could not secure one, off he would trot to a museum. There he would make sketches of it, then return and finish his illustration.

As if he needed another string to his bow, in the 1930s Matania began to write as well as illustrate stories in the monthly Britannia and Eve magazine. So famous did his historical illustrations become that renowned movie producers and directors sought his aid and advice. When Cecil B. DeMille was directing The Ten Commandments, he wondered if Matania could supply illustrations of his impression of the Israelites worshipping the Golden Calf. Matania did, and it is his interpretation that moviegoers see in the film.

Matania exhibited at the Royal Academy and the Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolors. A story is told of his tardiness in submitting his entry to the latter. Actually, he only started the work three days before “sending-in day.” The trailer of the story is that as he was carrying in the finished work, it was spotted by the famous American artist John Singer Sargent, then living in England. The picture, a splendid rendering of a scene from ancient Rome, was bought on the spot by Sargent—praise in itself.

There are several versions of the following story. Apparently Matania had been commissioned to illustrate an article entitled “King Solomon and His House.” He had very little trouble with the house—the Bible gives a good description. But, research as he may, nowhere could he find any helpful description or pictorial likeness of the son of David. As usual, there was a deadline, so he used his imagination. Several years later a national newspaper published a series about famous people of the past. Naturally, Matania was intrigued. Would they include Solomon? And, if so, what had he really looked like? Sure enough, Solomon was included, but when the Solomon story appeared Matania could hardly believe his eyes—they had used his interpretation! When questioned, the editor merely smiled and said, “If Matania had painted it, it had to be right!”

When deadlines were not a problem, Matania might work on a painting for more than two years. He was commissioned to paint battle scenes for several famous regiments. These are still hanging in various regimental messes and museums about Great Britain.

Matania’s passing in 1963 was recorded in The London Times as follows:

“Chevalier Fortunino Matania, who died in London on Friday, was one of the illustrators of the old school, his work being notable for his extraordinary finish and detail. It might almost be said that he continued the tradition of Alma-Tadema [Anglo-Dutch, 1836-1912, renowned for attention to detail, especially classical Greek and Roman life] in the form of popular illustration.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments