By Frank Johnson

Second Lieutenant David A. Sterling of the Scots Guards was serving with Lt. Col. Robert E. “Lucky” Laycock’s No. 8 (Guards) British Commando Battalion, based at Suez, Egypt, in 1941, when he got a novel idea.

Temporarily paralyzed from the waist down after an unauthorized parachute jump near Mersa Matruh, Stirling found himself confined for two months in the Alexandria Scottish Hospital. While recuperating, he thought about ways to make Commando hit-and-run raids against enemy bases and airfields more effective. Stirling reasoned that small teams of highly trained men could achieve better results than larger groups. Such teams could create confusion and chaos amongst the enemy and tie down offensive forces for defensive purposes.

The 25-year-old subaltern proposed in a penciled memorandum that four-man teams—with each member specializing in weapons, explosives, navigation, or signals—could venture into the Egyptian and Libyan deserts, with German and Italian supply lines, airfields, and ammunition and fuel dumps as their primary objectives.

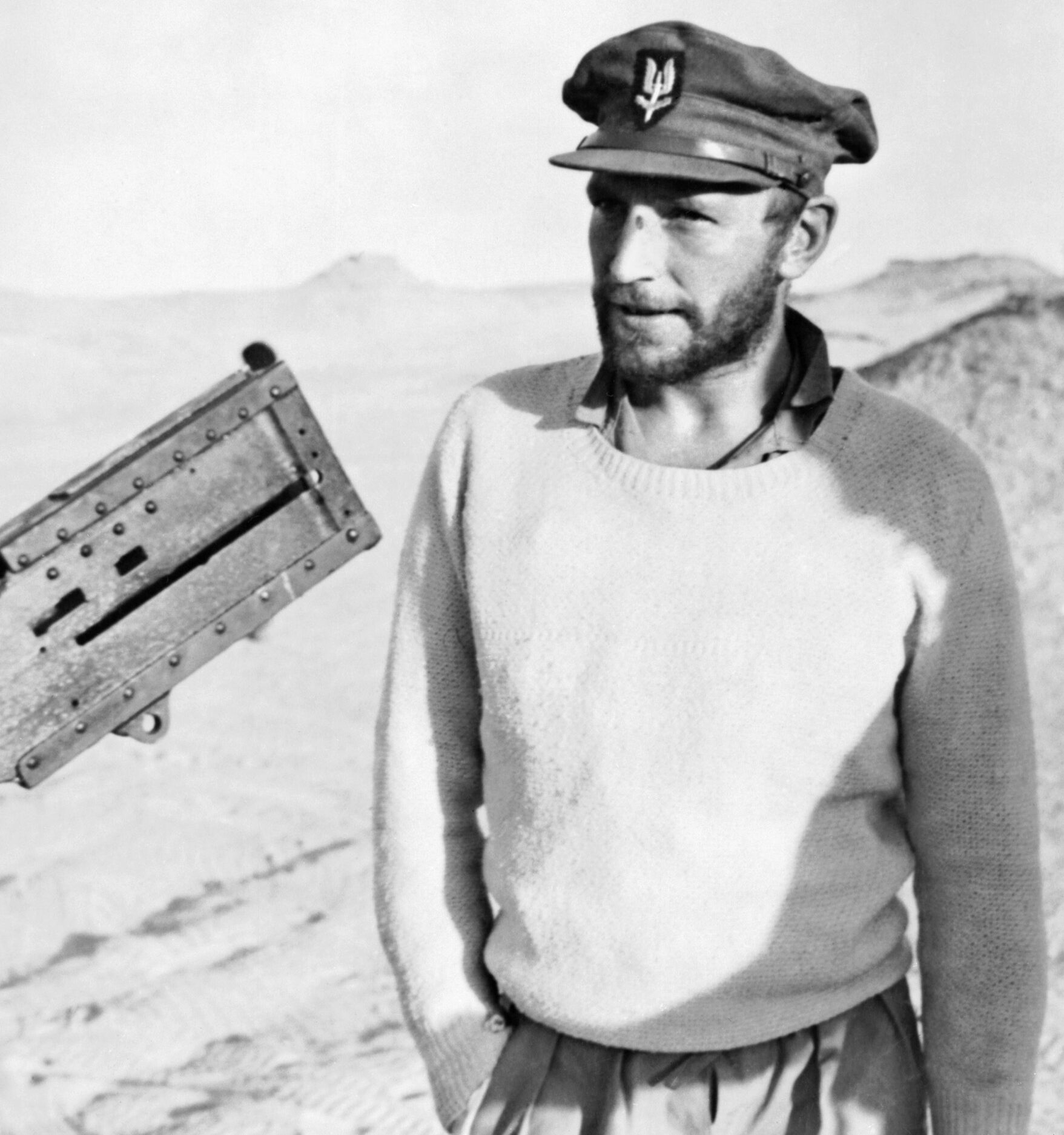

On his release from the hospital in July 1941, the tall, handsome, aristocratic Stirling felt he should bring his plan to the attention of General Sir Claude Auchinleck, commander of the British Middle East Forces. Commanders-in-chief in the British Army were not customarily receptive to being buttonholed by junior officers, but Stirling decided nevertheless to ignore the usual channels. He feared that unimaginative, middle-ranking officers would stifle his concept. So, he made his way to the General Headquarters in Cairo, used his crutches as a ladder to scale the perimeter fence, eluded sentries, and by a “rare bit of good fortune” found himself hobbling into the office of Auchinleck’s deputy, bearded Lt. Gen. Neil Ritchie.

Stirling apologized to the surprised Ritchie for his unconventional approach, and the latter read his memorandum and promised to discuss it with the C-in-C. For Auchinleck, new to the command and under pressure from Prime Minister Winston Churchill to mount an offensive, Stirling’s plan was just what he was looking for. It was original and required few resources.

Three days later, Stirling returned to the headquarters, this time with a pass, and met the dignified General Auchinleck. The C-in-C promoted him to captain and gave him permission to recruit a force of six other officers and 60 enlisted men. Thus, in July 1941, the British Army’s Special Air Service (SAS) was created. It would become one of the most elite and effective special forces of World War II and beyond.

Born in 1915, the son of Brig. Gen. Archibald Stirling of Keir, Stirlingshire, the maverick lieutenant had attended Ampleforth College in Yorkshire and Trinity College, Cambridge, from which he was sent down for gambling and drinking. His early ambition was to be a painter, and he was training for an attempt to climb Mount Everest when war broke out in 1939.

There were two particular officers Stirling wanted for his desert force and who promptly agreed to join. One was Australian Lieutenant Jock Lewes, a scholar, Oxford University rowing blue, and daring soldier who had carried out small raids on enemy desert outposts. The other, who would become Stirling’s second-in-command, was a fellow maverick who was under close arrest for striking his commanding officer. He was Ulster-born Captain Robert “Paddy” Blair Mayne, a prewar international rugby player.

By August 1941, Stirling had established his little force in a three-tent camp at Kabrit, 100 miles south of Cairo in the Suez Canal Zone. The initial unit was known as L Detachment of the Special Air Service Brigade. The name was a deception to convince the enemy that the British had a complete airborne brigade in the field.

Recruited within less than a week from the remains of Laycock’s Layforce, the volunteers were trained in special hit-and-run operations and survival. Stirling insisted on physical fitness, character, and a high standard of discipline equal to that of the Brigade of Guards. The training was rigorous, and anyone not up to scratch was immediately transferred to another unit. One of Stirling’s recruits, H.R. Fitzroy Maclean, who rose to brigadier rank, reported, “For days and nights on end, we trudged interminably over the alternating soft sand and jagged rocks of the desert, weighed down by heavy loads of explosive, eating and drinking only what we could carry with us. In the intervals, we did weapon training, physical training, and training in demolitions and navigation.”

Together, Stirling and Mayne shaped L Detachment into a tough unit ready for action, but equipment was sadly lacking. Captain Stirling, a self-described “cheeky laddie,” decided that needed gear would have to be “borrowed.” So, the detachment’s first— and highly unofficial—mission was a night raid on a New Zealand Division camp a few miles down the road. Stirling’s men loaded their only three-ton truck with anything useful that could be found and made off with.

L Detachment’s first official combat foray—a parachute drop—was a dismal failure. Five teams were dropped by five obsolete Royal Air Force Bristol Bombay transport planes on the black night of November 16, 1941, to attack five forward German airfields near Gazala in support of General Auchinleck’s Operation Crusader offensive. The operation was to precede Auchinleck’s attempt to relieve the besieged British garrison at Tobruk. But Stirling’s raiders were widely scattered by high winds and a sandstorm and lost their equipment containers. Only 22 men made it back to a rendezvous with the Long-Range Desert Group (LRDG), a roving, deep-penetration reconnaissance force that had been formed in July 1940.

Stirling, who was later promoted to major and then lieutenant colonel, was undeterred, but he abandoned the airborne concept in favor of overland operations in vehicles provided by the LRDG. The Special Air Service was back in business with its motto, “Who dares wins,” and a winged dagger as its insignia. The members were issued white berets, but after drawing derisive wolf whistles from other servicemen, the headgear was changed to khaki forage caps and finally sand-colored berets. The first members of the SAS, who changed the nature of warfare, came to be known as “The Originals.”

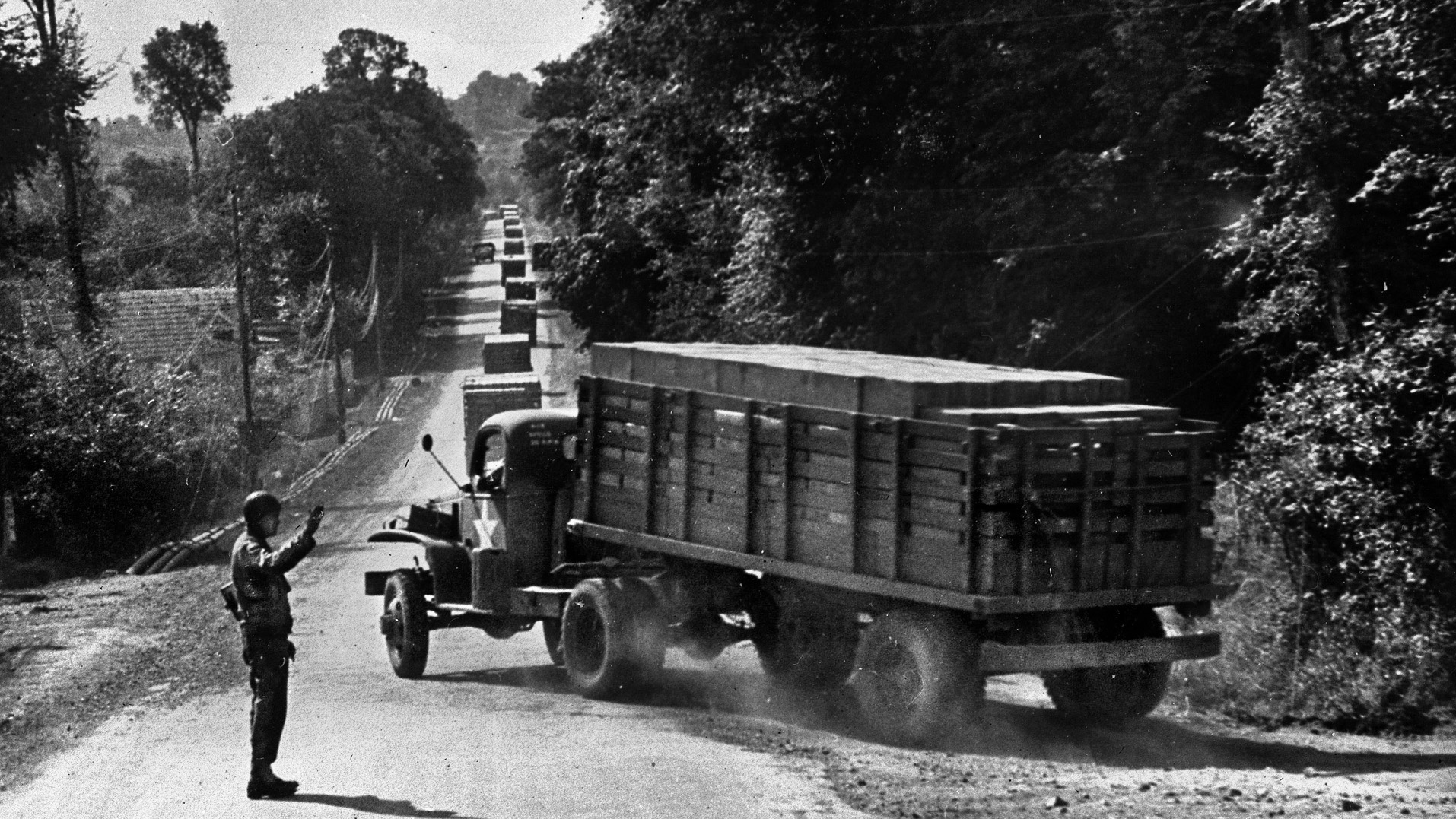

Bearded, disheveled, and wearing Arab headgear, Stirling’s irregulars ranged thousands of miles behind the Italian and German lines in the North African desert from 1941 to 1943. They drove four-wheel-drive Chevrolet trucks, Bentley touring cars, and later Jeeps laden with Vickers or Browning machine guns, small arms, Lewis bombs, Jerry cans, and water condensers. The freebooters subsisted on a makeshift diet of rock-hard Army biscuits, corned beef, chocolate rations, marmalade, tea, dates, snails, onions, turnips, and whatever else they could find in oases and Arab villages. When their water cans ran dry, the SAS irregulars had to resort to brackish, wormy water from wells.

The SAS grew rapidly, and by late 1942 had expanded to almost 400 men. Its operations extended, and by the time that the Western Desert war ended, it had been officially designated a British Army regiment, the 1st SAS. It included in its ranks some French paratroopers, Greeks, and even anti-fascist Germans. In 1943, a second regiment, the 2nd SAS, was raised under the command of Colonel Stirling’s eldest brother, William. It served with the British First Army in Tunisia.

During their audacious expeditions across the endless dunes, wadis, and scrub-dotted wastes, the SAS patrols destroyed an estimated 400 Axis aircraft on the ground, severed Afrika Korps fuel-and-ammunition railway lines multiple times, blew up numerous supply and bomb dumps, and made almost 50 assaults against key German positions. It was a harsh existence for Stirling and his men, but theirs was an unrestricted war far removed from the Cairo top brass and stifling military regulations. They were on their own in the desert, and morale was high.

Nothing save panzers could stop the SAS and LRDG raiders, and they were contemptuous of the enemy they harassed and eluded again and again. Frank Harrison, the driver for Lt. Col. David Lloyd Owen, reported, “We drove through a huge German Army camp. The cooks were just getting up. Odd fellows walking about, going to the lavatories and having a wash. We just drove through them waving. They waved back. Why not? Five trucks driving through your camp, in the early morning, waving to you, why not wave back? Can’t possibly be enemy, all that way behind German lines. Impossible.”

Nevertheless, danger dogged the irregulars’ tracks all the way as they tried to elude superior enemy forces and hide from reconnaissance planes persistently scouting them.

As Captain Malcolm J. Pleydell, the SAS medical officer, reported, “Although life was free and easy in the mess, discipline was required for exercises and operations. On the operations in which I was involved, our patrol would make long detours south of the battle line and then loop up north to within striking distance of an airfield or similar target. Camouflage had to be expert, so that when you hid up you couldn’t be detected — even at close distance. Slow-flying enemy aircraft could follow our tracks to our hiding places, and they represented a real threat. It was a hit-and-run, hide-and-seek type of war.”

Like the LRDG, the SAS irregulars became a painful thorn in the enemy side, and their leader was nicknamed the “Phantom Major” by Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, commander of the Afrika Korps. A reward of 100,000 Reichsmarks was put on Stirling’s head. He was a colorful figure in the British Army; his bravery was well known, and he was viewed as a man of vision and action, another Lawrence of Arabia. Some fellow officers regarded him as slightly mad, but as General Bernard L. Montgomery astutely pointed out later, “In war there is a place for mad people.” Stirling was soon promoted to lieutenant colonel.

His second-in-command, Mayne, was a boyish, hard-drinking former sportsman from Ireland whose exceptional leadership qualities were matched by great bravery, characterized at times as reckless and wild. Lieutenant George Jellicoe, who joined the SAS in 1942, described Mayne, who specialized in the destruction of grounded enemy aircraft, as “brave as 10 lions, a tactical genius.” A legendary figure like Stirling, Paddy Mayne became one of the two most highly decorated British soldiers of World War II.

As part of Stirling’s L Detachment, Mayne took part in a series of operations against enemy airfields and supply lines in the second half of 1941. He led a daring raid on an Italian airfield at Tamet in the Libyan desert that December, destroying 14 planes, damaging 10, and blowing up bomb and fuel dumps. Two weeks later, he went back and destroyed 27 more aircraft.

In only four months, the reputation of the SAS had grown, and Mayne’s personal count of enemy planes destroyed had risen to more than 100. It was bold, deadly work. After a raid one night on the base at Fuka, Mayne reported that the enemy had “posted a sentry on nearly every bloody plane.” He said, “I had to knife them before I could place the bombs.” He and his small team destroyed 17 aircraft that night. On one particularly busy night, Mayne destroyed no less than 47 grounded enemy aircraft. On another occasion, he put a plane out of action with his bare hands.

The SAS destroyed more than 400 aircraft in just over a year, and Paddy Mayne’s personal score was more than twice that of any Allied fighter ace in World War II.

The SAS attacks on German and Italian airfields proved essential to the success of early British offensives in the Western Desert. It was found to be more economical in terms of available resources to destroy enemy aircraft on the ground than in the air. German planes, particularly the Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters, were far superior to the British Desert Air Force’s overworked Hawker Hurricanes and obsolete Gloster Gauntlet biplanes and Gladiators.

Operations by Stirling’s SAS raiders continued with increasing tempo until the end of 1942, with the unit operating at one time from the Kufra oasis, 500 miles south of Tobruk. When the unit was expanded as the 1st SAS Regiment, Paddy Mayne took command of its A Squadron and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in recognition of his “special services.” His leadership qualities were about to be needed even more acutely.

On January 10, 1943, the legendary Stirling was captured when a special German unit ambushed his column in Tunisia. He managed to escape and join a group of Arabs, but they sold him to the Germans for 11 pounds of tea. The Phantom Major tried unsuccessfully to escape four times from a prison camp in Italy, and then spent the rest of the war at the impregnable Colditz Prison in Saxony, Germany.

Mayne, who had also become a British Army legend in the Western Desert, was promoted to lieutenant colonel and assumed command of the SAS Regiment until its reorganization into two units, the Special Raiding Squadron and the Special Boat Section. Then came the massive Allied invasion of Sicily, and the fighting Ulsterman was soon back in action.

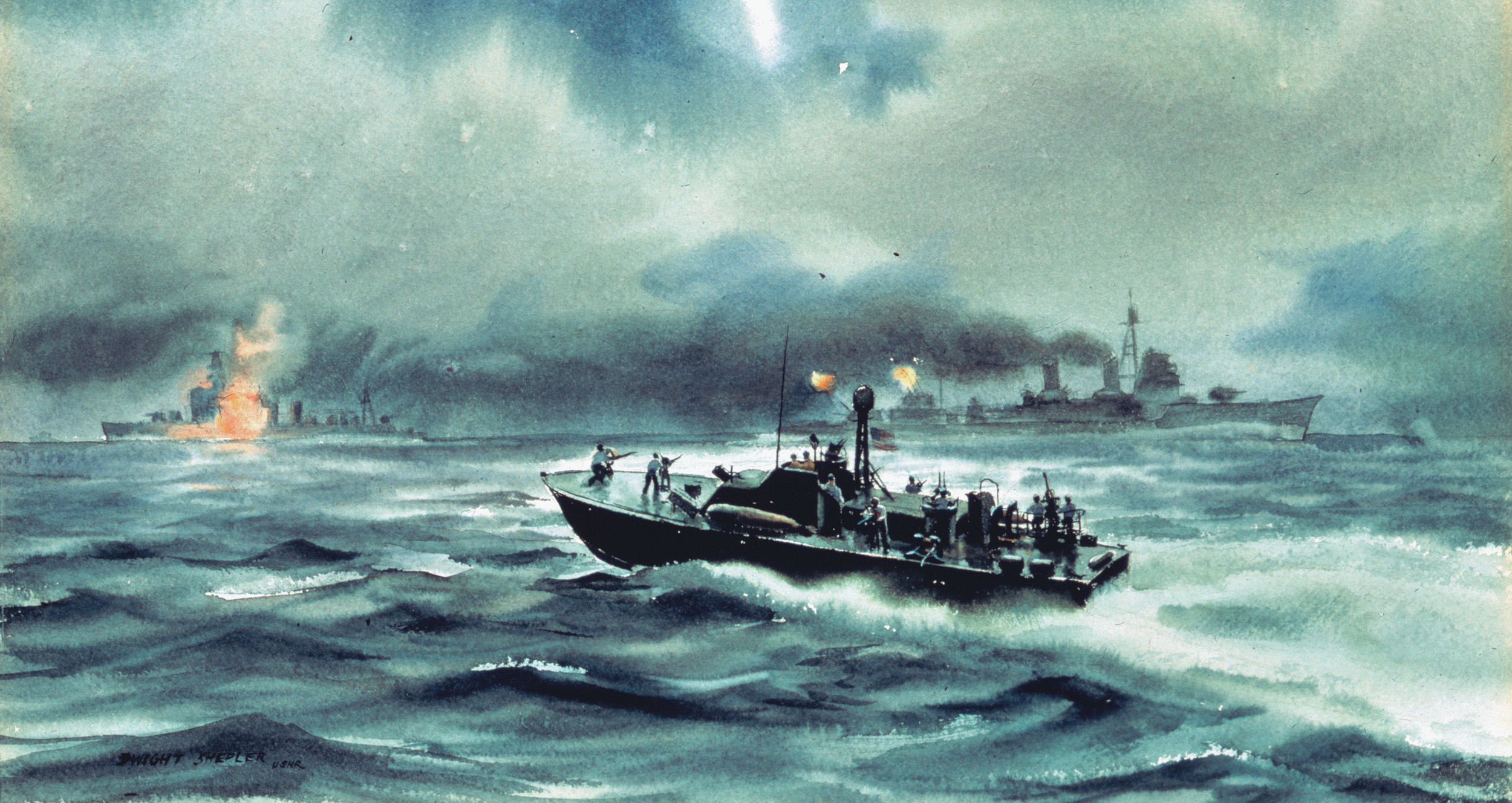

In the early morning hours of Saturday, July 10, 1943, General Montgomery’s British Eighth Army and Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.’s, U.S. Seventh Army landed in southern Sicily. Paddy Mayne led the Special Raiding Squadron as it splashed ashore from a landing craft just south of Syracuse, on the southeastern coast. Mayne and his men scrambled up a cliff and destroyed the Italian gun battery at Capo Murro di Porco. They captured entire the 700-man garrison within minutes.

Fighting on through the night, the SRS men destroyed six heavy guns, killed 100 Italians, and captured between 2,000 and 3,000 more. The operation was a complete success. Mayne was awarded his second DSO, and the citation said that his “courage, determination, and superb leadership … proved the key to success. He personally led his men from the landing craft in the face of heavy machine-gun fire. By this action he succeeded in forcing his way to ground where it was possible to form up ….”

There was little respite for Mayne and his men. After marching to Syracuse and being relieved by the British 5th Infantry Division, the SRS squadron headed for the port of Augusta, defended by the crack Hermann Goring Panzer Division. Using only hand grenades and small arms, the SRS raiders attacked the garrison on July 12, and had taken the port by late that day.

When Sicily was secured and the fighting switched to the Italian mainland, Colonel Mayne’s squadron was assigned the capture of Bagnara, north of the British Eighth Army positions around Reggio di Calabria. Landing in the early hours of September 12, 1943, the SRS unit ran into fierce resistance and was unable to clear the German defenders from the hills around the southern port. Mayne’s men dug in and fought off counterattacks for two grueling days before being relieved. They were then withdrawn to Sicily for a well-earned rest.

The final action for the Special Raiding Squadron in the Mediterranean theater came on October 4, 1943, when it landed with crack Royal Marine Commandos at Termoli on the Italian Adriatic coast. The SRS advanced into the port, secured it, and was then subjected to a strong German counterattack. During the bloody action, 22 of Colonel Mayne’s men were blown to pieces in the back of a truck. The battered unit hung on grimly for three days before managing to beat back the enemy, and Mayne was awarded a bar to his DSO.

While the 2nd SAS Regiment continued fighting in Italy until the war’s end, Mayne and his squadron returned to England in March 1944 to prepare for the planned Allied invasion of Normandy. The SRS was expanded and reverted to its previous designation of 1st SAS Regiment, joining the newly-formed 2,500-man SAS Brigade. The brigade comprised two British SAS regiments, two Free French regiments, and a Free Belgian squadron.

The SAS experiment had proved a resounding success during its valiant service in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. Brigadier Maclean observed, “Working on these lines, David (Stirling) achieved a series of successes which surpassed the wildest expectations of those who had originally supported his venture. No sooner had the enemy become aware of his presence in one part of the desert than he was attacking them somewhere else. Never has the element of surprise, the key to success in all irregular warfare, been more brilliantly exploited. Soon, the number of aircraft destroyed was well into three figures.”

Many tributes were paid to the SAS founder, Mayne, and their men. Lt. Gen. Sir Miles C. Dempsey, the able, unassuming commander of the British Second Army, told Mayne, “In my military career and in my time I have commanded many units. I have never met a unit in which I had such confidence as I have in yours.”

In the early months of 1944, the SAS men trained on the Scottish moorlands for their invasion role. They were to parachute behind German lines and establish a series of bases from which they could operate in strength. Then they were to harass the enemy, disrupt communications, gather intelligence for forward Allied units, and train and support French resistance fighters in sabotage. Blair was in command of the 1st SAS Regiment.

In the early hours of D-Day, June 6, 1944, SAS troops carried out diversionary parachute drops on the Cherbourg peninsula, west of the British, American, and Canadian landing beaches. Subsequently, until the liberation of Paris in August, Colonel Mayne and his comrades were engaged in a spoiling role from Abbeville as far south as Paris and the River Loire. Aboard jeeps mounted with pairs of twin Vickers K rapid-fire machine guns or .50-caliber Browning machine guns, the SAS irregulars raced through the countryside, shooting and blasting German units and installations at will.

With a touch of Celtic whimsy, Mayne had added two features to his Jeep—a public address system for “broadcasting rude words to the retreating Germans” and a phonograph on which he endlessly played Irish ballads.

The Germans reacted strongly to the irregulars’ bold forays because their desert reputation had preceded them. Despite their firepower, the SAS jeeps proved vulnerable in skirmishes with enemy armored units, and the regiment suffered its heaviest losses of the war. Many irregulars were captured and executed by the Gestapo. For his “fine leadership, example, and utter disregard of danger” in the Normandy operations, Mayne was awarded his third DSO. He also received the French Legion d’Honneur and the Croix de Guerre.

In the waning weeks of the European war, Mayne’s regiment took part with the Canadian 4th Armored Division in the final breakout through Germany, which ended at the Baltic Sea port of Kiel. At Oldenburg in northwestern Germany on April 9, 1945, as his regiment led the Canadian armor through enemy lines, Paddy Mayne’s actions in liberating a strongly-held village brought him a recommendation for the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest decoration.

When his forward squadron commander was killed, Colonel Mayne grabbed a Bren gun and, under fire and in full view of the enemy, dashed into several houses, killing and wounding the German defenders. Then he jumped into a jeep and cleared a path for the advancing British troops by shooting from the hip at the enemy. The big Ulsterman also rescued several wounded soldiers in the face of intense machine-gun fire. Then he calmly took charge of the situation, breaking “the crust of the enemy defenses in the whole of the sector.” At the end of the war, Mayne saw service in Norway, where the SAS Brigade disarmed 300,000 German garrison troops.

The citation for his VC recommendation said, “His cool and determined action and his complete command of the situation, together with his unsurpassed gallantry, inspired all ranks.” But the VC recommendation was turned down, perhaps through official disapproval of Mayne’s well-known rebellious streak. Colonel Stirling called the decision “a monstrous injustice,” and it was reported at the time that King George VI inquired why the VC had “so strangely eluded him.”

After the war, Colonel Stirling left the Army to settle in East Africa and moved later to Hong Kong. He died in 1990 shortly after being knighted, and a statue of him was erected in his former home at Doune, Perthshire.

Shortly after the SAS was disbanded on October 1, 1945, Colonel Paddy Mayne was demobilized. He was just 30 years old. Like many returning World War II heroes, he was restless and unsuited for a sedentary civilian life. He found respite in taking his pet dog for spins in his red Riley sports car along the roads of scenic County Down. He died at the age of 40 in a traffic accident in Newtownards while returning home early on December 15, 1955.

Fifty years after his death, a campaign to have Paddy Mayne awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross gained momentum when more than 100 Members of Parliament supported early-day motions charging that he had been the victim of a “grave injustice.” Ian Gibson, the Labor Party member for Norwich North, said, “We have had no satisfactory answers why he cannot be awarded the VC. It is small-mindedness.”

Although the Special Air Service had been disbanded in 1945, postwar insurgencies—particularly the Communist uprising in Malaya—soon ensured its revival and modification for new kinds of warfare. The 21st SAS (Artists Rifles) Regiment, a Territorial Army (militia) outfit, was created, and a special jungle-warfare unit known as the Malayan Scouts was raised by the colorful Brigadier Michael “Mad Mike” Calvert, a veteran of both the SAS and Major Gen. Orde Wingate’s famed Chindit columns in Burma.

The SAS became a potent force in the war on insurgencies and terrorism. After the Malayan Communists were subdued in one of the most successful campaigns of the 20th century, the highly-trained SAS irregulars served all over the world—in the Falklands War, the Persian Gulf campaigns, and such trouble spots as Borneo, Aden, Oman, Mogadishu, and Northern Ireland. An SAS team made headlines on May 5, 1980, when it rescued 25 hostages held by Arab gunmen at the Iranian Embassy in Prince’s Gate, London. SAS units also took part in the 1991 Gulf War and later Middle East operations.

The SAS remains one of the British Army’s—and the world’s—elite units.

Author Frank Johnson has studied World War II history for many years and resides in the United Kingdom.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments