By Blaine L. Pardoe

Count Felix von Luckner was known by many titles in his life: runaway, sailor, hero, braggart, fool—even spy. In some respects, all the titles were well earned, although some were more accurate than others. Luckner was born on June 9, 1881, in Dresden, Germany, the first son of Count Heinrich von Luckner. The Luckners were a cavalry family with a long history of service in the wars of Europe. Felix’s great-grandfather, Nicolas Luckner, was a marshal of France under Napoleon, leading the green-clad riding troops dubbed Luckner’s Cavalry. His name is memorialized on the Arc de Triomphe.

Felix went on a sailing trip as a boy and fell in love with the sea. His father would hear of no such talk from a Luckner. All the family’s men were expected to serve the emperor as cavalry officers. At the age of 13, tensions with his father reached a peak. Stealing his father’s raincoat and borrowing enough money from his brother to get by, Felix set off for Hamburg to become a sailor. An old salt named Peter Böemer found the young count wandering the dock and took him under his wing. He tried to convince the boy to go home, but Felix’s mind was made up. Boemer did convince him to take an alias so that his family could not track him down. Felix von Luckner became Phylax Lüdicke, taking his mother’s maiden name.

Böemer helped get Felix passage on the Russian merchant vessel Niobe, traveling between Hamburg and Australia. Felix’s time aboard Niobe hardened him to life on the high seas. The windjammer was an older ship and her crew did not speak German. He was given such menial duties as emptying latrine buckets and slopping the pigs in the lower decks. One day Felix fell overboard and nearly drowned. The captain reluctantly brought him back onboard and beat him for his clumsiness.

In Australia, Felix jumped ship and joined the Salvation Army, selling the War Cry in the streets. He held a number of odd jobs, from lighthouse keeper to bartender to champion wrestler. During this period he occasionally wrote to his parents to let them know he was still alive. After seven years away from home he returned to Germany and joined the naval reserves. His long-held alias was shed when he discovered that the commanding admiral was an uncle on his mother’s side. The admiral took the boy under his wing and helped the young officer graduate.

Luckner returned home wearing the uniform of an officer in the service of the German kaiser. Luckner was given a number of postings, but it was his service as a lifeguard that drew the attention of the royal court. He saved the lives of five people and was awarded several medals for courageous actions. This eventually drew the attention of Kaiser Willhelm II, who met and liked the well-traveled young officer.

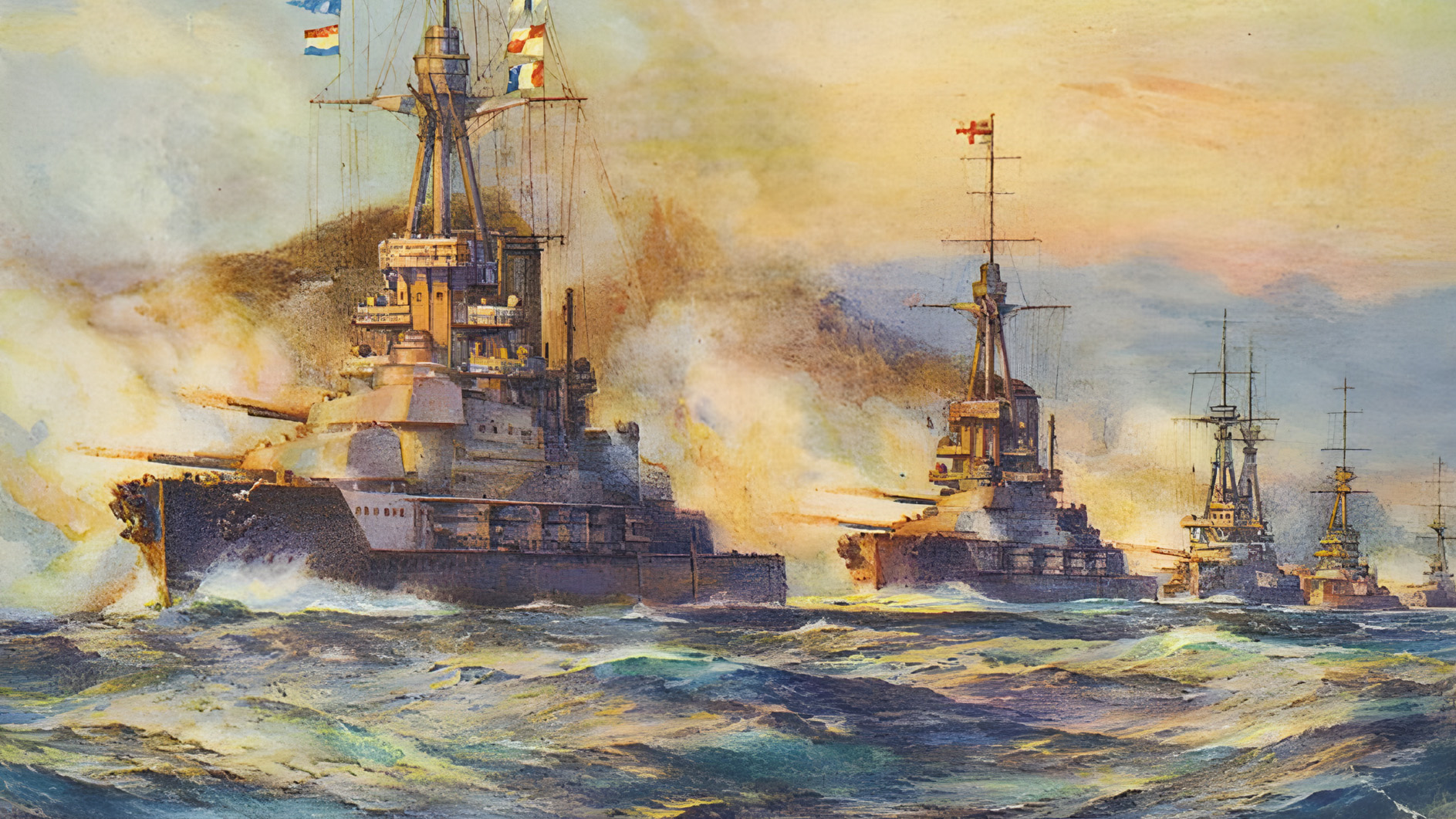

When World War I broke out, Luckner was posted as a turret officer aboard SMS Kronprinz Wilhelm. Turret duty was a dangerous assignment. Being surrounded by 100-pound bags of explosives in a hot, cramped space under enemy fire was often an express ticket to a quick burial at sea. Luckner fought in the Battle of Jutland in May 1916 and was fortunate enough to be aboard one of the ships that escaped damage.

After Jutland he was made a gunnery officer on the merchant raider Möwe (Gull). Möwe played a dangerous role in naval warfare for Germany—merchant raider. These were merchant ships disguised as neutral vessels. Hidden under a fake superstructure or false crates were good close-range deck guns. Under international law merchant raiders could falsely sail under a neutral country’s flag as long as they changed to their own national flags and their crews wore the uniforms of their respective countries in battle. The threat of raiders, proverbial wolves in sheep’s clothing, generated enough fear that some merchants would not even risk leaving port.

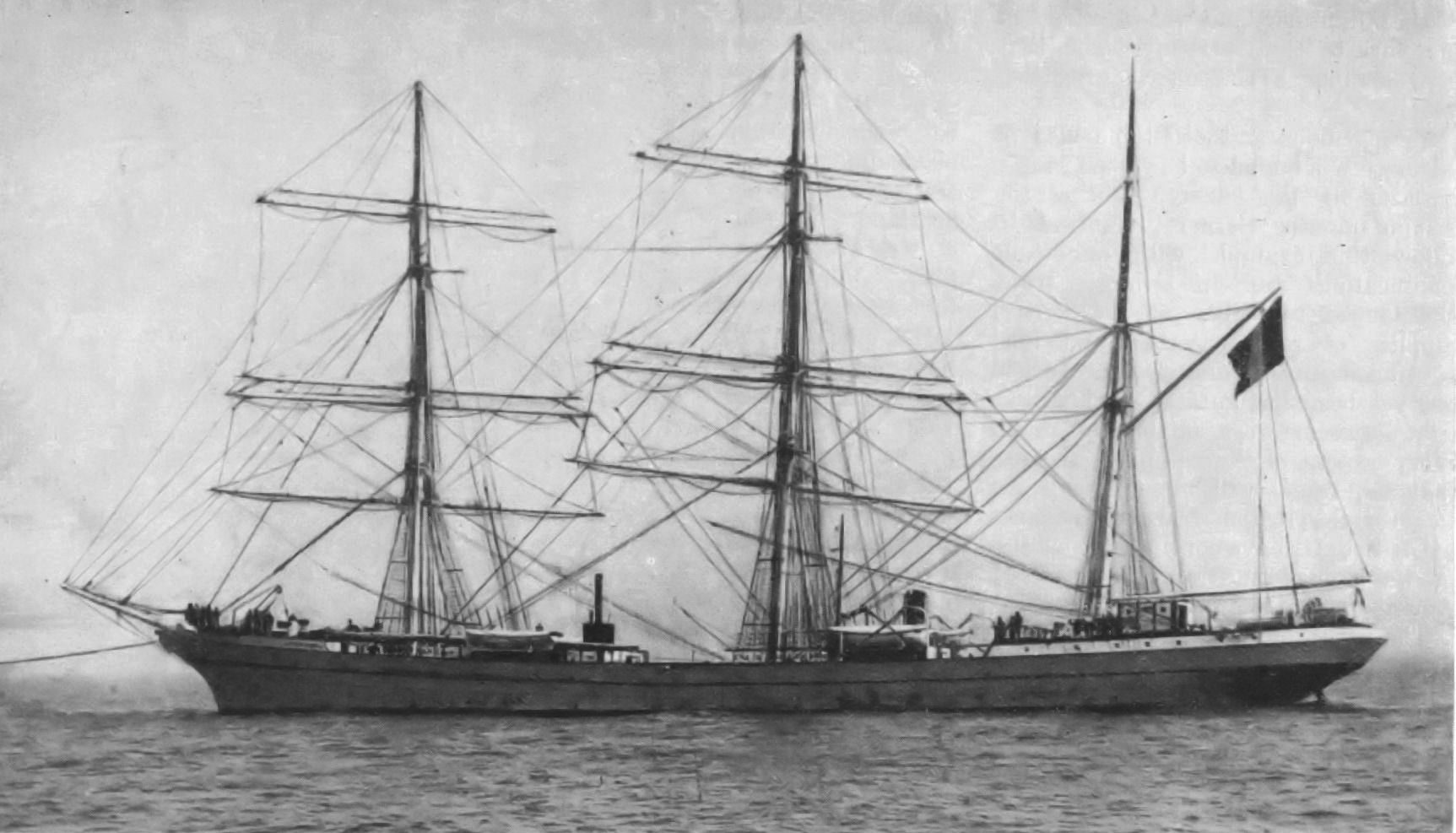

A year before the Germans had captured a three-masted American windjammer, Pass of Balmaha. An enterprising naval reserve officer, Alfred Kling, concocted the idea of using the wind-powered ship as a merchant raider. To most it was a ludicrous idea—this was the age of the battleship. A merchant sailing ship simply didn’t stand a chance if it was pressed into combat. But the idea was so out of left field that it just might work—the last thing the Royal Navy would expect.

The German Admiralty needed a qualified captain, someone with experience handling and commanding a large sailing ship. Of all the candidates in the German Navy, Luckner was the most qualified. The problem was that he was too young, 35, to be considered for such a role. The problem was solved by the kaiser himself. He simply predated Luckner’s commission so that he was qualified.

Pass of Balmaha was commissioned secretly as SMS Seeadler (Sea Eagle). Her crew was hand-picked volunteers because of the risks of its mission. Seeadler was covertly refitted for the assignment. Two 4.2-inch deck guns were mounted on her hull, hidden under tarps to appear like pigpens on the deck. She carried machine guns and a large arsenal hidden below decks. An auxiliary diesel engine was installed so that she could maneuver without wind if necessary. A wireless set was put in, its antenna hidden around the main mast. The captain’s mess was an elevator. At the proper signal, the entire floor dropped to the deck below where waiting marines could surround intruders.

The crewmen disguised themselves and the ship as Hero, a Norwegian merchant ship. A load of lumber stamped from a lumber yard in Norway was tied down to her deck, further helping to conceal some of her secret armaments. Luckner took an undercover trip to Copenhagen and stole the log of a similar vessel to help in the ruse. The crew was trained to speak Norwegian and its rooms were filled with trinkets and photos from Norway to help finish the disguise. One crewman even wore a dress and pretended to be Luckner’s Norwegian wife, a common sight on a merchant ship.

In December 1916, in a hurricane-force gale, Seeadler slipped out of German waters and into the North Sea. The ship was battered by the bitter cold, and her rigging and sails froze almost solid as she rounded England. The vaunted Royal Navy had pulled into port to avoid the storm, and for a while it appeared that Seeadler might escape completely.

On Christmas day that changed. The Royal Navy auxiliary cruiser Highland Scott appeared. Steaming up with the windjammer, she sent a boarding party to Seeadler to check her out. Everyone played their roles to the hilt. Luckner had soaked his own cabin with sea water to explain the unreadable ship’s log. The boarding party inspected the ship, never finding the hidden German crew in the lower decks. Highland Scott signaled for Hero to resume sail.

Luckner was supposed to head toward the Indian Ocean and attack other merchant sailing ships, but when the raider came across the steamship Gladys Royale, the crew signaled her for time (to synchronize their chronometers). The ship steamed in close, and suddenly Seeadler dropped her deck railing and put the ship under the targeting sights of one of her deck cannons. The German flag went up and the crew dropped its overcoats to reveal German naval uniforms, in compliance with international law.

Gladys Royale ignored orders to heave to. Luckner ordered a traditional shot across her bow. After several shots, the captain realized that this was no ordinary windjammer he had encountered and stopped her engines. With precision the crew was removed from the ship, supplies were taken from her, and the ship was sunk. The next day another ship, Lundy Island, was spotted. Like Gladys Royale, she attempted to get away, but Luckner gave her a warning shot as well. This time there was a surprise on board. The captain of Lundy Island knew the doctor of Seeadler.

Luckner’s string of captures continued as he moved between South American and Africa. Ships from France, Canada, Italy, and Great Britain fell to the German raider as Seeadler captured Charles Gounod, Perce, Antonin, and Buenos Aires. In all his initial captures, Luckner managed to avoid taking lives, even refusing to sacrifice a ship’s mascots or pets. He even captured Pinmore, a ship that he had sailed on as a young boy years before. With a sense of loss, he gave the order to send his former ship to the bottom.

Seeadler captured two more ships before she came across Horngarth, a British merchant steamer. Horngarth, which mounted a five-inch cannon, opted to take on Seeadler. Luckner’s crew lined the deck and pinned down Horngarth’s gunnery crew with rifle fire as he tried to maintain close distance. When his crew spotted a wireless shack on the ship, Luckner ordered the ship fired upon. The shack was hit and blown apart, causing the only casualty that Luckner inflicted in his raids, a young sailor by the name of Richard Douglas Page who was fatally scalded by a ruptured steam pipe. The next day, the crew and prisoners mustered on deck for his burial. Luckner conducted the service himself. There wasn’t a dry eye on the ship.

With more than 200 prisoners on board, Luckner was worried that the Royal Navy might catch onto his activities. He had temporarily detained a neutral Danish ship, Viking, and he knew that once she made port she would tell authorities about the German raider. On March 21, 1917, Seeadler captured a three-masted French ship, Cambronne. Luckner transferred his prisoners to the newly seized ship. The prisoners were elated at their newfound freedom. They cheered Luckner as he released them for the trip to South America.

As they passed out of sight, Luckner ordered Seeadler to head south and made a run for Cape Horn. If he was lucky, he could get through the storms there before the Royal Navy moved to intercept him. The running of Cape Horn from the Atlantic to the Pacific was treacherous in a sailing ship, even one with an auxiliary engine. The Horn was a churning, storm-filled sea of icy waters that challenged even the most hardened sailors. Luck was again on the side of Seeadler. The Royal Navy blundered in its patrol pattern, allowing the Germans to escape its net. To help alleviate growing merchant shipping fears and rising insurance rates, the Royal Navy falsely broadcast that Seeadler had been sunk.

By the time Seeadler entered the Pacific, the war had changed. The United States had declared war on Germany. In June and July 1917, Luckner captured three American merchant ships: A.B. Johnson, R.C. Slade, and Manila. But Seeadler was beginning to experience problems. Her freshwater supply was dwindling, and the crew was showing signs of scurvy and beriberi. Luckner made the decision to put in at an isolated island to reprovision the ship and let his crew rest for a while on land—the first time in seven months. The island he chose was the small atoll of Mopelia in the Society Islands, a narrow circle of land surrounding a pristine lagoon 280 miles from Tahiti.

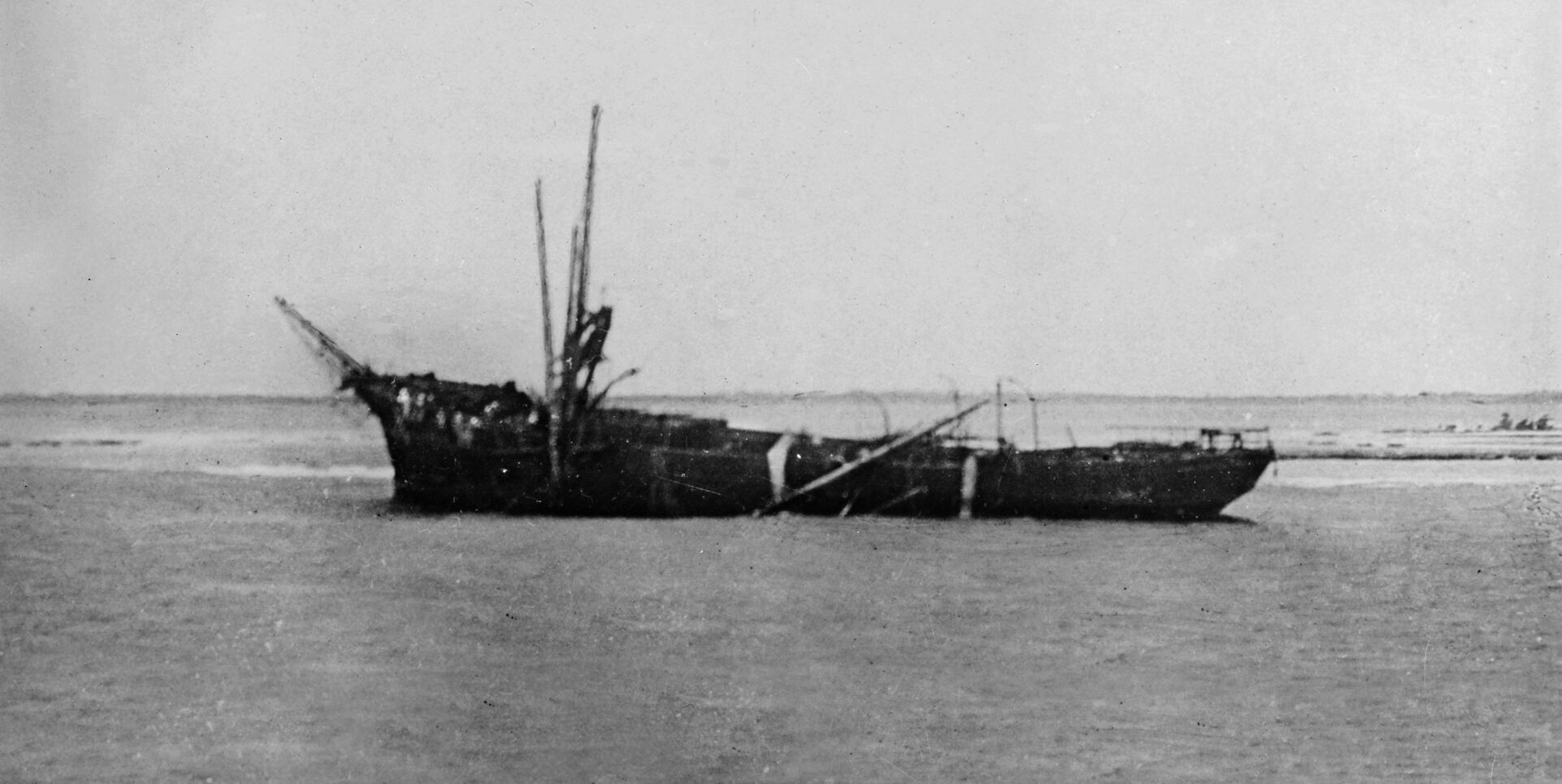

The crew found the lush green island teeming with rats, insects, and other irritants, but also with fresh fruit. It seemed to be a perfect home until one morning when the crew was scraping the hull and the current changed. Seeadler slipped her anchorage and smashed into the coral reef, puncturing her thin metal hull in several places. In a matter of hours, the ship was a total loss. The crew and her 46 American prisoners were literally shipwrecked.

The Germans and Americans settled in on the tiny island, creating two tent cities. Even with the salvaged supplies from the ship, the small island would not be able to support the survivors indefinitely. Luckner and his officers came up with a solution. Taking one of the two motor launches that Seeadler had carried, they outfitted it with a mast and set sail across the Pacific. With any luck a small crew might find another ship to capture and return to Mopelia, where it could pick up the remaining castaways and continue the mission. If not, the stranded crew might be in a position to capture a ship passing by. Either way, remaining on Mopelia indefinitely was not an option.

After days of outfitting, the tiny launch was christened Kronprinzessin Cecilie and ready to go. With five men, Luckner set off across the Pacific in search of another ship to steal. Three days later they reached Atiu in the Cook Islands, representing themselves to New Zealand authorities as Norwegians who had undertaken a gentleman’s bet to sail the Pacific in an open boat. They were given supplies and sent on their way. After days in the scorching sun with salt-sprayed clothing rubbing their skin raw, the crew reached Aitutaki and again tried their cover story—only to find it half-heartedly believed by the locals.

Kronprinzessin Cecilie set sail again, heading toward Fiji. The small ship sailed 3,000 miles through vicious storms, baked in the sun. Eventually, the exhausted sailors reached Katafangato, then moved on to Wakaya, where they spotted several ships that might prove vulnerable to capture. Before they could enact a seizure, however, the suspicious locals rallied against them. A constable boarded the boat armed with just a pistol. The crew carried a machine gun from Seeadler, as well as several rifles and grenades—enough firepower to take control of the entire island if they wanted. But since they were not under a German flag or wearing German naval uniforms, if they acted against the constable they would be labeled spies or pirates and could be hanged for their actions. Rather than risk his men’s lives, Luckner surrendered to the stunned policeman. Eventually, the prisoners were taken to New Zealand, where they became celebrities. Except for an abortive, eight-day escape attempt, Luckner spent the remainder of the war in New Zealand.

The Germany to which Luckner returned was dramatically different than the one he had left three years before. Germany had suffered deeply in the war. Its people were starving, and there were open street battles between Fascists and Communists. Luckner’s return brought hope. Here was a man who had sunk more than $25 million worth of Allied ships and cargo. Luckner was a hero in the eyes of his fellow Germans. Children wore hats stitched with his name or that of Seeadler.

In an effort to rebuild after the war, Germany sent its most respected hero to America on a goodwill tour to promote German industry and business. It was a stunning success. Former prisoners had told stories of decent treatment under Luckner’s command, and he was warmly greeted everywhere he went. Henry Ford gave him a new car as a token of thanks. San Francisco and Miami made him an honorary citizen; the Boy Scouts named him an honorary scout master. Luckner spoke to audiences from school gymnasiums to Carnegie Hall. Americans embraced the gallant count almost as one of their own.

After the Nazi Party took control of his homeland, they hoped Luckner would continue to be a good spokesperson for their cause, but the count refused to disavow his honorary American citizenships or his membership in the Masons, and he was excluded from joining the Nazi Party. He did consent to Nazi funding for a cruise to Australia and his old stomping grounds in the Pacific. The Nazis hoped he would help ease tensions there, but Luckner proved to be an uncooperative spokesman, sometimes causing more public relations problems than he smoothed over. He cared more about revisiting old Seeadler triumphs than about promoting the Nazi cause.

Upon his return to Germany, Luckner was ostracized by the Nazis. He was brought before a court of honor on trumped-up charges of misuse of government funds and personal misconduct. Although not convicted, he was placed under house arrest, his books were banned, and he was forbidden to speak in public. He was too popular to kill but far too uncooperative for the Nazis to leverage for their own purposes.

Near the end of the war, the mayor of Halle, where Luckner was living, asked the count to negotiate a safe surrender of the town to the onrushing Americans. Driving through the German lines carrying a scrapbook of his adventures and escapades as a form of ID, Luckner miraculously located Maj. Gen. Terry Allen and negotiated the town’s surrender. His actions saved countless lives and preserved Halle as one of the few German cities untouched by the ravages of war.

Hitler issued a death order for Luckner, but it was never carried out. Within a month, Hitler himself was dead, and the Third Reich had fallen. Luckner spent several weeks with General George S. Patton, himself an avid sailor. Return to his hometown became impossible after the Russians took possession of Halle. The count retired to Malmo, Sweden, with his Swedish-born second wife. He returned to Germany only once, to bury his brother.

After World War II, interest in Luckner faded away. Because of the ban on his books, an entire new generation did not know who he was. Even worse, some of his own people saw Luckner as a traitor, and he was cut off from his family estate. An aging symbol of a bygone era, Luckner died in Malmo in 1966. His obituary was front-page news around the world. When he was interred in Hamburg, thousands lined the streets to salute the old “Sea Devil” one last time.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments