By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

Thousands of dead Turkish soldiers choked the river and littered its bank. It was the fall of 1697 and the young Imperial Field Marshall, Prince Eugene of Savoy, had just vanquished the Ottoman army at Zenta (or Senta), on Hungary’s River Tiza. His decisive victory brought about the 1699 Peace of Karlowitz and the end of the Second Turkish War (1683-1699) that had pitted the Holy Alliance of Poland, Venice, Russia, and Austria’s Holy Roman Empire against the Ottoman Turks. With the exception of the Ottoman Banat (a border march) of Temesvár, the treaty left Austria in possession of all of Hungary and Transylvania.

Eugene thus became a European hero and Austria a major European power. But peace had scarcely been secured in the east when the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714) broke out in the west. It pitted the Grand Alliance of England, the Netherlands, and the Empire against the French and Spanish. Together with his friend, the brilliant Duke of Marlborough, Eugene won several great victories for the allies.

In the east, however, the smoldering Turkish Empire was not yet finished, not by a long shot. Like their foes, the Ottomans regarded the Karlowitz treaty as little more than an armistice. The Ottoman Empire of Sultan Ahmed Khan III Najib (who ruled between 1703 and 1730) still spanned over two million square kilometers. With such a vast territory and burgeoning population, it was only a matter of time before the Ottomans would recuperate their manpower losses. In 1710 that time came. Infuriated by Russian border violations and new fortifications in the Ukraine, the Porte (Ottoman High Command) declared war on Russia.

A year later, an outmaneuvered Russian army submitted to the Ottomans after a lengthy standoff on the River Pruth. Humiliated, Peter the Great accepted an unfavorable peace treaty that returned Azov and other fortresses to the Ottomans. With the Russians cowed, the Ottomans used a Venetian-inspired uprising in Montenegro as an excuse to resume their war with Venice in 1714. Grand Vizier Damad (also known as Silahdar) Ali-Pasha, the Sultan’s son-in-law and personal favorite, led the Turks in an assault on the Venetian Kingdom of the Morea (the Greek Peloponnese). The Ottomans were not so foolish however, as not to realize that their victories in Russia and in the Morea unnerved their old archenemy, Austria.

Vienna basked in the summer heat of 1715 when, in a pompous ceremony, Ibrahim, the Sultan’s müteferrika (a member of the Ottoman palace ‘elite’) walked up to a seated, short and wiry individual who was surrounded by the chief Imperial officers of state. This was Eugene, now in his fifties and president of the Hofkriegsrat (the Imperial War Council). Though a plain brown tunic was his more usual attire, in light of the occasion Eugene now wore gold-embroidered red silk.

From under his broad brimmed hat, Prince Eugene eyed the Turkish representative. The müteferrika presented a letter from the Grand Vizier Damad by which Damad expressed his hope for the Emperor’s neutrality in the Ottoman war with Venice. It was a not to be. Damad might as well have wished for the moon.

Eugene fully realized that no matter how cordial the Turks presented themselves, it was only a matter of time before the Ottoman behemoth swung towards the Empire. In April 1716, on Eugene’s urging, in April 1716 Emperor Charles VI of the Imperial House of Hapsburg renewed Austria’s old alliance with Venice. Consequently, Charles VI insisted that the Ottomans adhere to the treaty of Karlowitz and return to Venice all the lands they had taken.

On May 15, 1716, the Porte answered Austria’s demands with a declaration of war. The Morea had already fallen to Grand Vizier Damad in the late summer of the previous year and the Venetians were hard pressed to hold onto Albania and the Dalmatian coast. The Porte was free to direct the brunt of its martial might against Austria. Leading it would be none other than the Grand Vizier Damad Ali-Pasha.

At Modon in the Morea, Damad had paid a reward for every Christian brought to his tent so he could personally relish the sight of their decapitations. He also executed any Turks who had been foolish enough to embrace Christianity while under Venetian rule. Now he wrote to Eugene, “there is no doubt that the blood which is going to flow on both sides will fall like a curse upon you, your children and your children’s children until the last judgement.” Damad inspired his own commanders with the words, “attack the infidels without mercy … Be neither elated nor down-hearted, and you will triumph.”

For the first time since Suleiman the Magnificent (1490-1566), war in the Balkans was forced upon the Ottomans instead of the other way around. This suited Eugene just fine because by fluke more than by design, European power politics following the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714 resulted in an unusual period of peace in the west.

The chief catalysts for this peace were the 1715 death of Austria’s old European enemy, France’s dynamic Louis XIV, and the resurgence of the Whig party in England in 1714. Louis XIV was succeeded by his great grandson Louis XV. In the event of the child King’s death, his regent, the Duke of Orleans, was more worried about safeguarding his own claim to the throne from his rival claimant, Philip V of Spain, than in starting new wars. England’s Whigs meanwhile were too occupied with the Jacobite opposition and the danger of rebellions to get involved in Continental struggles.

Thus, Eugene was free to concentrate on the Turks in the east, which is what he really wanted to do. Moreover, Pope Clement XI offered 500,000 florins from church lands for the effort, which he considered a crusade. Nonetheless, the brunt of the war costs would fall on Austria. Indeed, unlike the previous two Turkish Wars, this one was to be virtually an almost exclusively Austrian war. The Venetians were busy defending the Ionian Islands, and of the German princes, only Max Emmanuel of Bavaria sent a sizeable contingent of troops.

The collection of an army had commenced and made substantial progress even before the Porte’s declaration of war. Difficulties in the form of droughts and floods intervened and Eugene himself remained in Vienna until July 2, 1716, to make sure of sufficient supplies and funds, but his diligence paid off. After a ride of only seven days he reached the village of Futak, north of the Danube and west of the fortress town of Peterwardein (Petrovaradin), the “Gibraltar of Hungary.” There he beheld his army of 65,000 men, which he described to be “in a very fine serviceable condition.” His comments were in stark contrast to those he made in 1697 when he had been given command of an Imperial army in which there “are many diseases but only a little money.”

Through their thick walrus mustaches, Prince Eugene’s troopers no doubt cursed and muttered over the usual hardships of war. Theirs was a hard life. They fought not for cause and country but for money. Though hardy peasant louts were the favorite source of recruits for the Imperial Army, most of the soldiers—like those of all 18th-century armies—were from the bottom of society: vagabonds, criminals and beggars, especially in the infantry. Productive tradesmen and farmers were usually exempt from military service because they kept the economy healthy. Only through strict, at times excessively brutal, discipline were recruits welded into formidable fighting machines. Nevertheless, Eugene’s soldiers, flushed with recent victories in the Rhineland and with unabated confidence in a leader who genuinely cared for their well being, were ready for a fight.

Eugene’s officers hailed from a stratum of society completely opposite to that of their men, yet one which—like that of their men—was generally unproductive: the nobility. Eugene had personally chosen most of his senior officers. Commanding the infantry were the bold Field Marshal Prince Alexander von Württemberg and the eccentric Field Marshal Sigbert Heister. Eugene personally disliked Heister whose extreme brutality in past dealings with Hungarian rebels had backfired for the Imperials, causing Heister to be hated and feared all over Hungary. On the other hand, there was no denying Heister’s personal daring, bravery and unrelenting tenacity.

Leading the cavalry were Field Marshal Count Johann von Pálffy, whom Eugene considered an able if not too bright corps commander, and General of Cavalry Ebergenyi. Eugene’s favorite was the gifted Count Florimund von Mercy, whose main shortcoming was that his career was marred by bad luck.

The time taken for preparation by Eugene allowed even the slow moving Turkish army to reach Belgrade. Grand Vizier Damad Ali Pasha took nearly three months to cover the 440 miles from Istanbul with his 120,000 strong army. The elite Janissary ‘Ocak’ corps had not fully recovered from the defeat suffered at Zenta, but still made up some 40,000 infantry of the total host. Another 30,000 were Spahis, paid professional Ottoman cavalry. Tartar, Wallachian, Egyptian and various Asiatic auxiliaries composed the remainder of the Ottoman army. Though the Tartars were superb raiders, they and the rest of the auxiliaries were of doubtful value on the battlefield. Many of them still fought with outdated weapons like bows and arrows. Indeed the distinction between many “auxiliaries” and the additional tens of thousands of camp followers, who had no combat value whatsoever, was blurred.

With the wheat ripening in the summer heat and his army’s supplies ensured, Damad set out from Belgrade. Typically breaking at dawn and making camp at noon, the Ottoman army crossed the River Sava on July 26 and 27. Their vanguard probed towards Hapsburg Karlowitz beyond which lay Damad’s objective, Peterwardein. Imperial scouts reported that the Turks were closing. Based on their reports, on July 28 Eugene wrote the Emperor that the entire enemy host numbered 200,000 to 250,000 men, a considerable overestimation.

Count Pálffy volunteered to lead 900 Austrian cavalry, 400 Hussars (light cavalry) and 500 infantry on a reconnaissance mission. Eugene hesitantly approved but only after he explicitly ordered Pálffy to avoid any engagement. Pálffy headed out and Eugene received word from him requesting reinforcements. Eugene dispatched two more cuirassier regiments and again warned Pálffy to avoid a fight. Pálffy had little choice, however. On August 2, shortly after the cuirassiers joined him, over 10,000 Turkish cavalry took Palffy by surprise. The location was near the very chapel where in 1699 the peace of Karlowitz was signed.

The battle that ensued raged for four hours as Pálffy desperately fought his way back toward Peterwardein through difficult terrain cut up by trenches and hollows. Two horses were shot out from under him. Among the wounded were Lt. Field Marshal Count Hauben and Oberstleutnant Freiherr von Owen. Lt. Field Marshal Count Siegfried Breuner’s horse was also killed, and he was captured by the Turks.

At dusk Pálffy’s company could see the walls of Peterwardein ahead of them in the gathering gloom. The Turks were so close on Pálffy’s heels that his men could probably hear the ground rumble beneath the hoofs of the Spahis’ steeds. Ahead there were chaotic shouts, and soldiers running here and there forming a firing line as the fortress walls lit up with the flashes of cannon fire. Only then did the Spahis reign in their sweat-covered steeds and back off from Pálffy’s soldiers.

Pálffy had made it back by a hair’s breath, having lost 700 killed. Eugene conceded that the fiasco should not have happened and the less said about it the better.

In the meantime, Eugene built a bridge of boats to move his army over the Danube. Then on the night of August 4/5, he deployed it in a new position south of Peterwardein. The soldiers occupied an entrenchment left from a battle that had occurred outside Peterwardein’s southern walls 22 years previous. Eugene had hoped to take Belgrade, but Damad had to be dealt with first.

Grand Vizier Damad pushed on toward Peterwardein, where he found Eugene’s army awaiting him in front of the fortress. The Turks encamped to the south, on the escarpment of the Frusta Gora. Under the protection of a barrage of Turkish heavy guns, the Janissaries dug trenches to within 50 paces of the Imperial lines and deployed in a huge half-moon formation, engulfing the whole Imperial camp. Sporadic artillery fire erupted from the Imperial side.

Orta Imams (battalion chaplains) recited holy prayers to Allah an hour before sunset. Though the Janissaries were devout Muslims and technically “slaves of the sultan,” most followed their own unique brand of Sunni Islam known as the Bektasi dervish sect. The more tolerant Bektasi beliefs incorporated old Turkish pagan, Buddhist, Shia, Kurdish Yazidi and even Christian elements, and appealed to the Janissaries who were of multicultural origin. Regardless of their religion, on both sides soldiers no doubt prayed that God grant them victory over the unbeliever.

Elated by his minor victory over Pálffy, Damad immediately demanded Peterwardein’s surrender. He received no answer from Eugene, who from his own tent could see the Vizier’s pompous pavilion across the lines. It was part of a vast tent city erected by an army over twice the size of his own.

In light of such adversity, Eugene’s officers urged him to fall back into Peterwardein or at least remain in the current entrenchment. Others even advised a retreat back over the Danube. Their mutterings faded into the background as Eugene drifted into his own thoughts. A morass to the left and a steep precipice to the right flanked Eugene’s current position. The fortifications of Peterwardein were even more formidable. But to hide behind walls and to let his soldiers’ morale wither away like the walls of the fortress? That was not Eugene’s way.

He had fought the Turks for many years. The span was great: from the huge 1683 relief battle of besieged Vienna—when as a young man he had joined the Emperor’s army with nothing more than a sword and his steed—to the end of the Second Turkish War, when he, now a Field Marshall, crushed the Ottomans at Zenta. Eugene knew that almost nothing could withstand the initial rush of the Turkish juggernaut. But once committed, or taken by unorthodox tactics, the Turkish army quickly lost discipline and control.

Eugene would do what no one expected. Taking a deep breath, he spoke three words: “We will attack!”

Eugene, however, did not rush into action. In typical manner he soundly worked out a battle plan for his 64 battalions and 187 squadrons. His battle scheme’s 31 points went into such detail as suggesting that if called upon to fight in close combat, the commanders should ask their infantry to ditch their cumbersome jackets. Every infantryman was issued 50 bullets, every cavalryman 25 bullets, and every Grenadier four hand grenades.

Eugene deployed the bulk of his infantry behind the foremost entrenchment in three lines under the command of Heister. Max von Starhemberg commanded the right wing of the first line, while Feldzeugmeister (Quartermaster-General) Regal commanded on the left. The second line was under Feldzeugmeister Prince Bevern and Count Harrach. Holding the third line as a reserve was Feldzeugmeister Freiheer von Lõffelholz.

Outside of the entrenchment and to the left and front of the main lines, Prince Alexander von Württemberg commanded another six infantry battalions of 700 men each. Behind him was Count Pálffy’s cavalry, including Mercy, Ebergenyi and others. A storm played havoc with the ship-bridge and delayed the arrival of some last minute infantry and cavalry, which were still on the right bank of the Danube, but at 7 am, on August 5, all was ready.

Von Württemberg opened the battle with rousing success. The Turks were momentarily stupefied, unable to comprehend that Eugene was taking the fight to them! With virtually no opposition Württemberg seized the Turkish trenches and a battery of 10 guns lying in his front. Turkish footmen streamed away from his battalions and into them rode Pálffy’s cavalry, armored Austrian cuirassiers and Hungarian and Croat Hussars in their flamboyant attire.

Things did not go so smoothly for Eugene’s center, however. Eugene had deployed behind the outer entrenchment. Now, as Heister’s infantry moved forward, the entrenchments themselves served as an obstacle that broke up the lines. At this opportune moment Damad released his soldiers. In “unbelievable fury,” as Eugene put it, and with thunderous bellows the Janissaries poured forth toward the Imperial center.

Damad stood at his tent, beneath the green holy banner of the Prophet fluttering in the wind. He gleefully watched as the lines of pearl-gray Imperials reeled before his red-clad Janissaries with their elaborate turbans or their typical white “Börk” hats. Fired up by the bombastic clamor of the Ottoman Mehterhane military band’s huge kettledrums, clarinets, trumpets and cymbals, each Janissary fought as an individual. Jannissaries considered the infidel’s way of fighting to be more “like robots rather than warriors.”

Ottoman müskat tüfenkleri (flintlock muskets), pistols, Yatagan (reversed-curved swords) and two-handed axes took their toll on the soldiers of Starhemberg and Regal’s line, which wavered, fell back and threatened to collapse. Even the battalions of Bevern and Harrach’s second Imperial line took to flight. Sixteen Imperial standards fell into Turkish hands.

Disaster was temporarily averted by the Imperial cavalry. The dashing cuirassiers, in ridged helmets and black bullet-tested breast and back plates, stopped the Janissaries in their tracks. From behind the Imperial horsemen, Peterwardein’s guns “boomed,” their shot ripping into the Turkish lines.

In contrast to Damad, Eugene rode around the battle on his white charger. At times he could be seen in the foremost ranks, where he assessed the situation and gave quick and vital orders when needed. Calm and in control, Eugene observed that in the heat of the battle the Turks had neglected their flanks. He noticed that Württemberg’s advance had continued unabated. Sabers flailing and horses rearing, Spahis gathered to throw back the Imperials, but they shattered against Eugene’s stout Austrian cuirassiers coming at them in tight order. With the Spahis fleeing the field, Württemberg diverted to swing inward and strike the Turkish masses in their right flank. Eugene deduced that the decisive moment in the battle had arrived. He quickly gathered several thousand cuirassiers and sent some galloping to Württemberg’s support while others, under Ebergenyi, spurred their horses against the Turkish left flank.

The Imperial infantry took new heart when Eugene himself rallied the fleeing soldiers. Flintlock muskets cracking, bayonets fixed and supported by Lõffelholz’s reserves, the Imperial lines moved forward once more. Still watching the battle, Damad frowned and his thoughts turned to prayer. Attacked from three sides, his Janissaries valiantly defended their ground until the pressure became too much. Order went to hell; it did not matter if it was an elite Janissary or some unwilling Wallachian auxiliary, each soldier sought only to escape the Imperial vise. Tearing through the panicked Ottoman horde, the cuirassiers’ carbines and pistols blazed, and their basket-grip straight-bladed heavy ‘pallasch’ sabers were flashes of crimson speckled light.

Seeing his soldiers in headlong flight, Damad grasped his saber, swung onto his horse and charged at the infidels at the head of his troops. Yet fate did not reward his bravery. An Imperial musket ball hit him square in the forehead, knocking him off his horse. Incredibly, the wound did not instantly kill Damad. Dying, he was whisked off to Karlowitz, there to be strangled by order of a furious Sultan. Also killed at Peterwardein were the governors of Anatolia and Adana, Türk Ahmed Pasha and Hüseyn Pasha, respectively.

The wild pursuit of the routed Ottomans carried on through their artillery, their tents and their baggage. Close to noon, Eugene arrived at the Vizier’s tent where he beheld a horrific sight. There lay the corpses of 200 murdered Imperial prisoners. Among them the mutilated and beheaded Count Breuner, captured in Pálffy’s earlier cavalry engagement. Blood still poured from Breuner’s wounds and chains still bound his neck and feet. Such cruelty, however, was not limited to the Turks; Eugene later impaled Turkish spies found among his Serbian troops.

The Imperials claimed 30,000 Turks killed for a loss of 3,000 dead and 2,000 wounded of their own. The Ottoman number likely included countless camp followers indiscriminately hacked down during the chaotic rout. In the words of one of Eugene’s officers, “We took no more than twenty prisoners because our men wanted their blood and massacred them all.” The Janissaries, the only Ottoman troops who fought with skill and elan, probably suffered between 6,000 and 10,000 casualties. Those of the Spahis, who nimbly fled the battle and abandoned the Janissaries to their doom, were minimal. Seven months later the renowned English writer Lady Mary Wortley Montagu visited the battlefield and recalled that “ the marks of that glorious bloody day are yet recent, the field being strew’d with the skulls and carcasses of unbury’d men, horses and camels.”

The loot was unbelievable. An eyewitness described the Turkish tent-city, with its multicolored pointed roof pavilions as a “gigantic flower-bed full of every kind of blossom.” There were 172 cannons, 156 banners, five prestigious horsetail standards, thousands of wagons, tents, camels, horses, gemstone-studded weapons, Persian carpets, fine fabrics, and an array of other treasures. It took three hundred carts three days to carry it all away. A historian of the times noted that “if the spoils had been sold at their full value, and the money distributed amongst the soldiers, they would have had enough to have lived upon comfortably for the rest of their lives.” The Turkish war chest was discovered early by a couple of Imperial troopers who greedily filled their knapsacks, their shirts, and even their hats. The holy banner, though, escaped the Imperial clutches and was safely brought to Belgrade.

In Damad’s magnificent tent, surrounded by the Vizier’s treasures, Eugene wrote his dispatch to the Emperor. The tent was so large that it had required 500 men to erect. Eugene claimed the tent as his prize, everything else he left to his soldiers. Further, it was his soldiers, not himself, whom Eugene praised in his dispatch: “God the all mighty…blessed the Imperial arms with which the enemy was completely knocked out.”

On Eugene’s order, three hundred cannon salvos heralded his victory throughout the countryside. Eugene’s young regimental cavalry commander, Count Ludwig Khevenhüller, who had distinguished himself during the battle, rode to Vienna to deliver the news to the Emperor. On August 8 when Charles VI got Eugene’s message, the normally stiff emperor could barely contain himself with joy. All of Vienna danced with glee and Khevenhüller was mobbed by people who wanted to hear the story again and again.

Emperor Charles VI promised Eugene substantially more financial war aid. The jubilation spread to Rome where every church bell rang in Eugene’s honor. A grateful Pope sent Eugene a blessed violet biretta trimmed with ermine, decorated with a dove figure and embroidered in pearls, and a gem-encrusted sword and scabbard as long as Eugene himself. Even from France there were congratulations. Marshall Villers, who himself had once been bested by Eugene, praised the Imperial army and prophesied that Eugene’s campaigns would take him to the shores of the Black Sea.

Eugene had little time for his accolades or the Pope’s sincere if not ridiculous gifts. It was already too late in the season to consider an assault on Belgrade. Instead, on August 13 and 14, Eugene left Peterwardein and pressed on toward Temesvár, the capital of the Banat of Temesvár. Pálffy, with some infantry regiments and cavalry, had been sent ahead to cut off the fortress-city’s supply line.

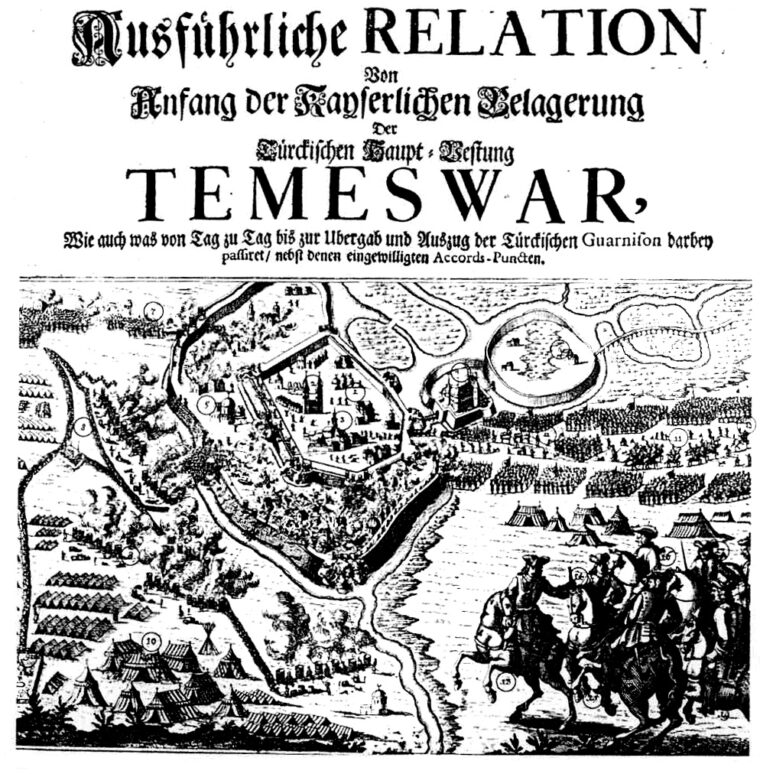

Eugene had his men march at night to avoid heat exhaustion. One of them described the campaign as “far more tiring and arduous than on the Rhine or in the Netherlands.” The Imperials reached Temesvár on August 26. The operation demonstrated Eugene’s logistical skills, as 80 guns and 30,000 hand grenades were brought over from Vienna alongside a 70,000 daily bread ration.

Temesvár was the last remaining Turkish fortress in Hungary and had been in Turkish hands since 1552. They nicknamed it the ‘Gazi’ (victorious) fortress. It had new fortifications built by 13,000 Wallachians forced into labor after they were unable to pay their taxes to the Ottomans. A river and a marsh gave further protection.

Mustafa Pasha defended the stronghold with ten to fifteen thousand elite troops. When asked to surrender, Mustafa Pasha retorted that Eugene may well have taken fortresses stronger than Temesvár but it was Mustafa’s duty to hold to the end for the honor of the Sultan.

A siege commenced. On September 23, after nearly a month, a relief force of 20,000 Turkish cavalry arrived. Four thousand of the Turkish horsemen carried a second ‘Janissary’ rider, who presumably jumped off to fight on foot. This relief force, three times larger than the army of the besiegers, battered at the section of von Pálffy’s encampment but were defied and finally driven off by Max von Starhemberg’s resilient defense. They left behind 4,000 dead.

On October 1 Prince Alexander von Württemberg’s Imperials breached the Turkish trenches and moat and penetrated into the stronghold. Although the defeat of the Turkish relief force had dashed Mustafa Pasha’s hope for victory and the Imperials were drawing ever closer, Mustafa Pasha refused to submit. Even Eugene was beginning to despair. Autumn rains filled the trenches and Imperial casualties amounted to 2,407 dead and 4,190 wounded. Finally on October 13, after relentless Imperial bombardment and an imminent uprising by Temesvár’s citizens, Württemberg beheld a white flag on one of the towers.

It was over. The city itself had suffered horribly, with most of its houses having burned to the ground.

During the battle, the fortress commander’s son was seriously injured. When Eugene heard of it, he sent a surgeon to help. The Turks in turn sent a younger son as hostage and a gift of six horses. Such chivalry, sadly rare in the otherwise brutal Turkish wars, further marked Eugene’s remarkable treatment of the defeated.

Eugene allowed Mustafa Pasha and his remaining soldiers an honorable retreat to Belgrade. Muslim families could depart with all their belongings, wagons, horses and livestock. Monies and supplies were given to reduce their hardships. Serbs, Jews, Armenians and Gypsies could stay or leave as they wished. Even more amazing was Eugene’s answer to Mustafa Pasha’s request that the Hungarian rebels who had fought under the Turkish banner be allowed safe passage as well: “The rabble can go where it wants,” he said.

The Banat now lay at Charles VI’s feet but it was Eugene who successfully initiated its recovery from long years of war and desolation. Craftsmen and peasants streamed in from Germany, enticed by subsidized travel costs, land grants, free tools, fuel, corn seed and six years tax exemption for craftsmen. Temesvár was rebuilt and earned the nickname of “little Vienna.”

The effects of Eugene’s victories in 1716 rippled through Eastern Europe. In the churches of Wallachia, the people and the bishops prayed for Austrian deliverance from the Turkish yoke. All winter long Imperial raids struck into Bosnia, Serbia and Wallachia. The fall of the Banat was not lost on the Turks. Ottoman Grand Admiral Kapudan-Pasha broke off his lengthy siege of the citadel on Corfu, set sail and left. The Porte suddenly talked of peace and found support from the English, who wished to curtail Imperial power. Eugene, however, would have none of it, and Charles VI followed his advice.

After setting up the frontier guards and leaving Count Florimund von Mercy in charge of the Banat, Eugene returned to Vienna for the winter. There followed numerous festivities in his honor, but Eugene was rarely seen at any of them. While the nobles, laughed, ate and danced in their Baroque palaces, his thoughts were ever toward the southeast. The war was not yet over and the next year he would strike at the prize that so far had eluded him, Belgrade.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments