By William McPeak

Collecting handwritten documents and letters on military subjects is as long-standing as military history itself. By general definition, when a letter is written and signed by a person, it is considered a holograph (or autograph letter), but a document is something written by an official or servant and then signed by an important person. Foremost on the list of important people would be a king, queen, or a noble or commander at a significant military event. But collecting also includes any significant letter or document, regardless of who might have written it, such as orders, lists, personal accounts, commissions, commendations, even drawings and sketches from the field.

Collecting any written artifacts dating before the 12th century means collecting dried and treated skin. Everything then was written on parchment (sheepskin) or the more durable goat and vellum (calfskin), which replaced the papyrus exported from Egypt before 600 bc. Paper appeared in Europe sometime during the 12th century, coming from China via the Middle East. But paper was not prevalent until the 14th century. It was fragile compared to vellum or parchment, but it proved to be much cheaper to make.

There are some European documents with commanding signatures from the 7th century, but usually the signers were popes, not kings. In general, early European royal documents were intentionally kept simple. A scribe or secretary did the writing and other preparations. Most medieval kings and military leaders did little writing—because they could not. Instead, an official stamp or seal (attached with a leather thong, a cloth or silk) began to be used on royal documents and correspondence to lend them further authentication.

A document authenticated as signed by William the Conqueror and auctioned in 1932 contained a large, ornate X at the bottom. The conqueror of England could not write, so he made his mark and his name was added by his scribe. Other kingly signatures were illegible scrawls—just variations on the X. These were illiterate kings—ruling, not writing, was what was important to them. In England, all kings prior to Richard II (1367-1400) are assumed to have been unable to write.

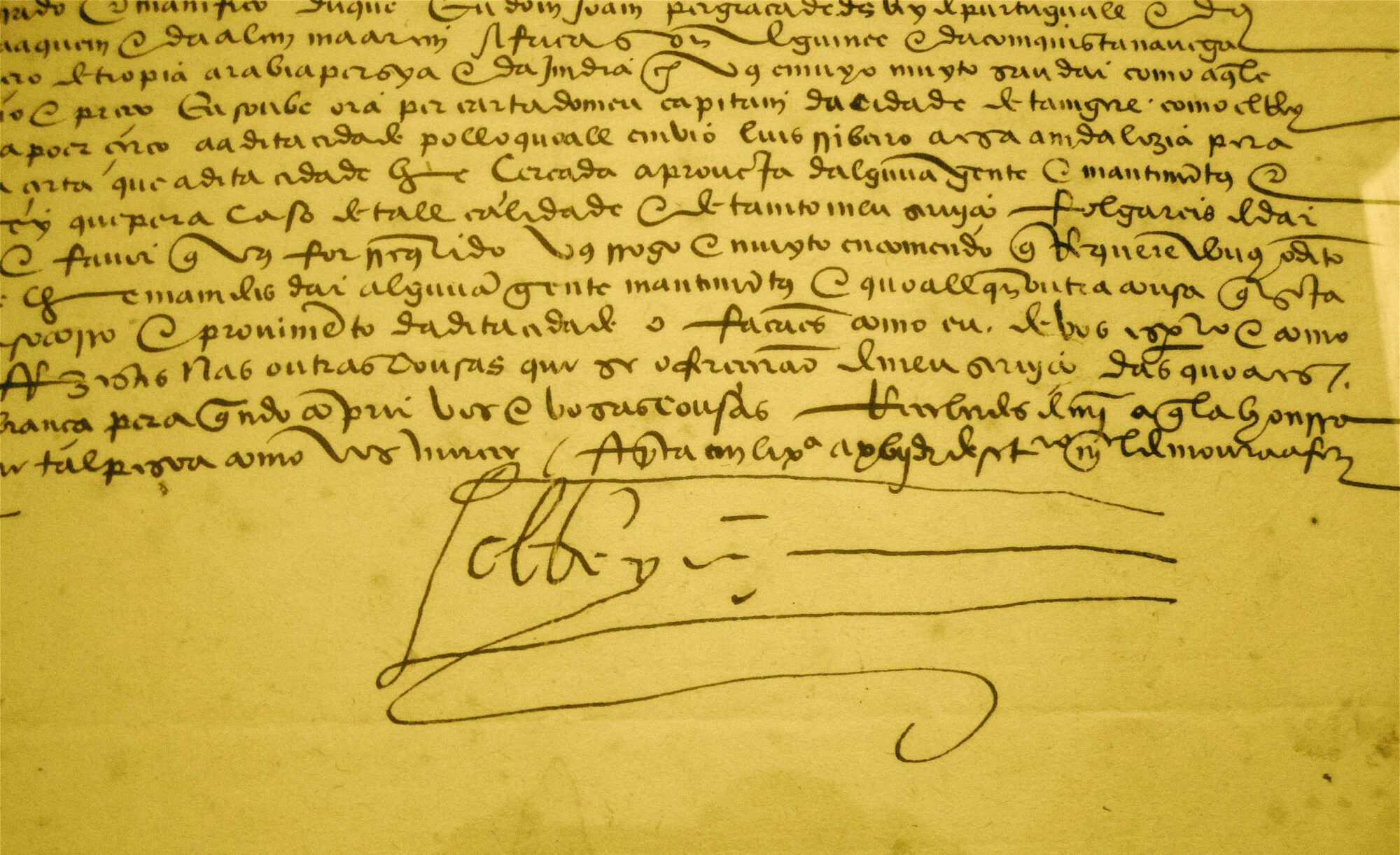

It should be noted that many royal signatures are simply “the King” or “I the King.” An example of the latter is a military call for assistance by King John III of Portugal, the brother-in-law of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1519-1556). John III was married to Charles’s sister Catherine, and the short letter on paper, written in Portuguese and dated September 17, 1529, came from Lisbon and concerned a matter of military urgency. It was addressed to the Duke of Arcos in Andalusia. Islamic North Africa was a constant flash point for Iberian royalty. The king was asking the duke to send troops for the relief of Tangier, Morocco, which was then being besieged by the Islamic king of Fez. The body of the letter was in the hand of the king’s secretary, but John boldly signed it “El Rey.”

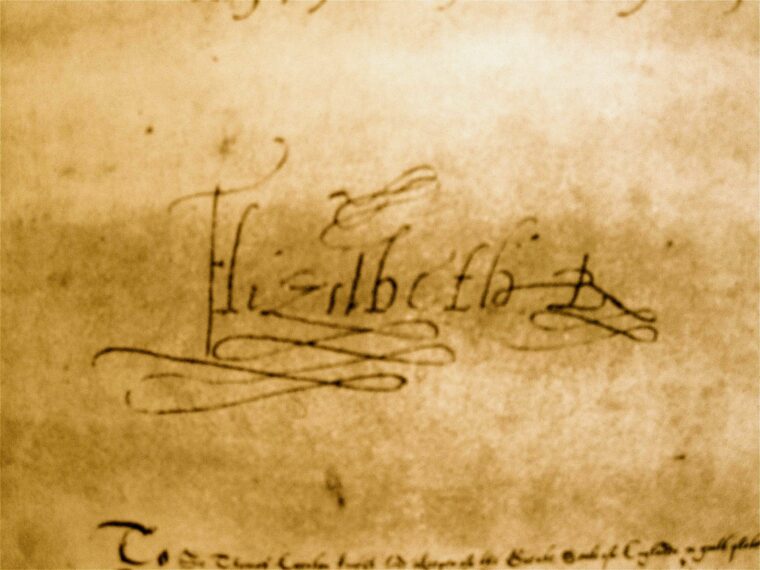

Even in more literate times, most European kings were infrequent writers, yet documents signed by monarchs represent the greatest source of preserved documents, simply because of the sheer amount of government business. Henry VIII of England was lazy enough—he called writing “painful”—to have a wooden stamp of his signature made up. Ironically, the monarch who most relished writing and signing official documents was his daughter, Queen Elizabeth I. Her penmanship was excellent, and she indeed had a huge signature—“Elizabeth R”—that is considered a calligraphic work of art. And although it appeared on important historical documents dealing with such epochal matters as the defense of the realm against the Spanish Armada, Elizabeth’s signature on more commonplace documents is also highly prized.

Kings and queens who ruled the longest are logically the sources for the most signed documents dealing with royal business. Conversely, those whose reigns were cut short by death or deposing represent more intriguing and valuable subjects for collectors. One monarch whose signature is quite rare and consequently quite valuable is England’s much-maligned King Richard III, the last of the Plantagenet line, who reigned for only 21/2 years before being killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485.

How government-related documents were handled opens another window for collectors. Much of the day-to-day interplay of government business within a kingdom involved an army of scribes and secretaries who moved mountains of vellum and paper from point A to point B. Keeping track of documents and making copies was essential—the original could be destroyed so easily—and in the days without photocopiers, that was where the scribes came in. Their job was to make several copies of all documents received or sent. They wrote quickly and used various forms of abbreviation to improve efficiency.

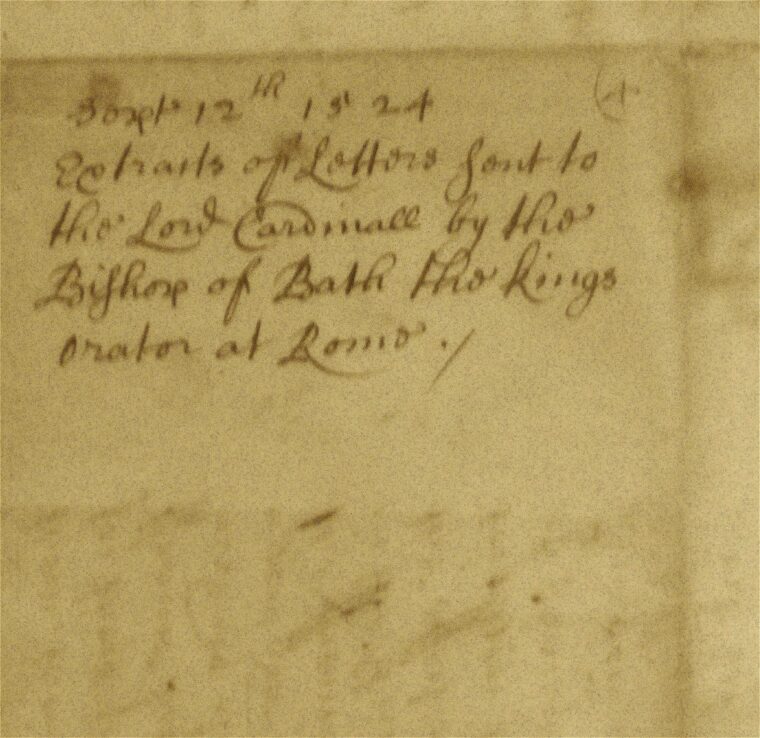

Among the potentially most historical court documents were diplomatic dispatches and reports. Sent by the king’s various representatives in foreign countries, they were the backbone of politics and diplomacy. A monarch’s official diplomat at a foreign court, his ambassador (in England he was called an orator), usually wrote a report once a week to summarize all significant events. These reports could take two or three weeks to arrive, but they were still the quickest means of relaying events.

A case in point was the secretary’s copy, in English, of a dispatch to Henry VIII’s powerful chancellor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, from his diplomat at Rome, Bishop Hadrian of Bath. Probably copied in late September or early October 1524, the original dispatch was dated September 12 of that year. The scribe has written on both sides of the page and put a reference title on a folded side so that it could be filed and found easily. Dealing with events relating to the first Hapsburg-Valois War between Charles V and King Francis I in Italy, the dispatch mentions the emperor’s siege of Marseilles by Charles, the Duke of Bourbon, who had fled France and joined the emperor as commander of his forces. Also mentioned is a secret mission by a French envoy to the Swiss cantons to contract troops for the war. Additionally referenced are spying missions in Avignon by Bourbon’s cousin Philibert de Chalon, Prince of Orange, his second in command.

From the 17th century onward, the growing importance of the written word was amply reflected by the increased number of royal letters and documents passed down to the present. The amount of military correspondence from the field grew with the higher level of literacy among officers and the necessity of quickly adjusting plans of battle. With the arrival of the small field telescopes to help with reconnoitering and scouting, hurried reports on tactical updates became increasingly essential.

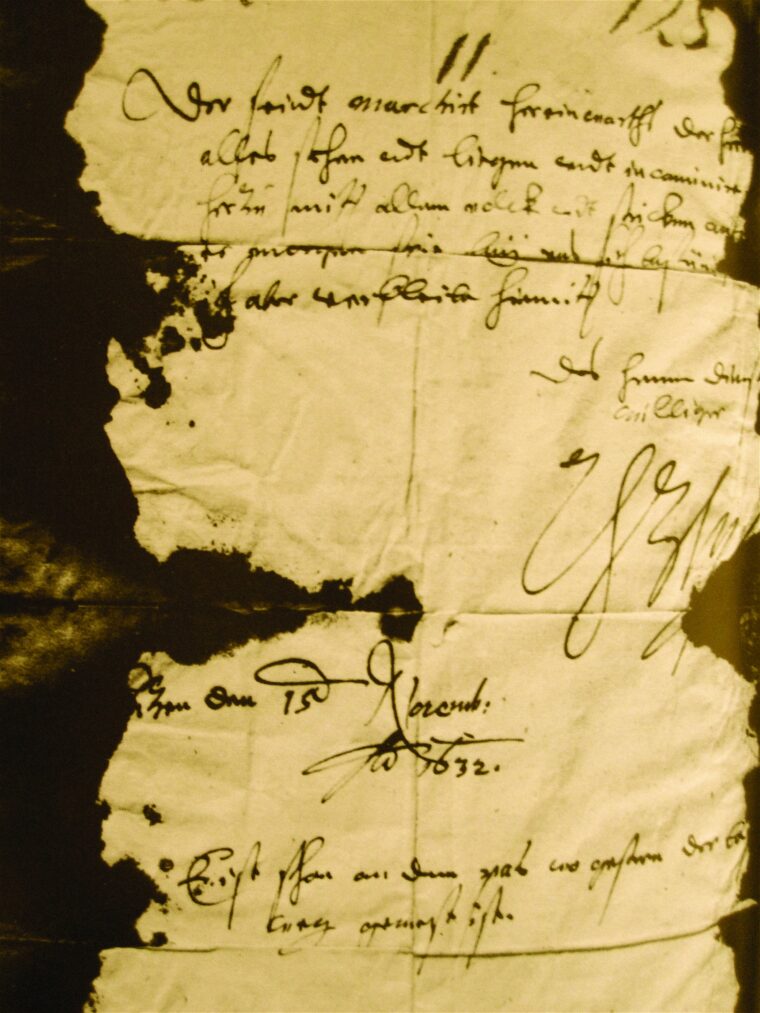

One of the most momentous battles of the Thirty Years’ War occurred at Lützen, Germany, on November 16, 1632, where Swedish King Gustavus lost his life and his imperial rival, Albrecht von Wallenstein, lost his best cavalry general, Gottfried Pappenheim. The latter had taken the cavalry to intercept Protestant reinforcements, but Wallenstein had messengers standing by to recall his commander of horse. Wallenstein penned a now-immortal note to Pappenheim with a summons in the universal Latin used for communications at the time. The note was delivered folded and headed: “Cito Cito Citissime Cito” [Quickly! Quickly! With greatest speed! Quickly!].

Pappenheim received the note and returned with phenomenal speed, arriving by 3 pm and joining the battle with a fury. But as he charged for the Swedish right, a cannonade from Swedish guns sent a large, molten shard of shrapnel that cut into his armor like a can opener and opened the whole left side of his body. Pappenheim was mortally wounded. Beneath his armor and his blood-soaked doublet was the blood-stained note that is preserved to this day.

The great store of available documents written on vellum and paper did not become a passion of collectors until the 19th century, when dealers began combing through European stately homes and their library archives. Historically minded collectors came on with a vengeance. Among the most avid was Sir Thomas Phillips, who collected a staggering one million vellum documents of all sorts. Most of the collectors were moneyed Americans with a special relish for their own history, and large collections came together quickly built around such specialties as George Washington and other Revolutionary War leaders, Abraham Lincoln, Civil War generals, and presidents.

Early-19th-century collectors, unfortunately, were joined by that element always on watch for criminal profit—the forgers. Letters, documents, and autographs are among artifacts most easily faked, and quality forgeries began to appear in relatively little time. Many of the 19th-century forgers’ techniques are still used today. Duplicating pre-19th-century iron-based inks is a simple process—as is obtaining goose quills. One easy and therefore frequent forgery was to fake a famous signature among unknown signatures on an authentic but relatively obscure document. In other cases, letters were faked using genuine paper of the time and an able modern penman, or by writing on modern rag paper that had been stained with tea or coffee to give the document in question the appearance of aging.

It is safe to say that many if not all noteworthy autographs have been forged: all European monarchs, all prominent Civil War generals—especially in the 1880s with a resurgence of interest in that conflict—and many European military leaders. Some forgers were very sophisticated, others ridiculously simple, such as a Bowery tramp dubbed “Autograph Smith” who could fake any famous signature—especially those of Washington and Lincoln. In some cases, the forgery was unwitting. Many French nobles had their secretaries forge their signatures, and many of Napoleon’s orders after 1800 were signed by his secretaries since he was so busy with war itself. Then there are the stamped signatures, instances of a reproduced signature but not the real thing.

The would-be collector of the written word has many things to consider: historical period, subject, type of manuscript form (letters or documents), and price. But first and foremost is locating reputable dealers. They have a professional standing to uphold and guarantee as authentic what they sell. The physical state of a document is also paramount. Nothing brings down the price of a paper letter or vellum document faster than water staining. Also, royal or government documents are worth more with the attached royal seal. High-profile collecting means spending big money: a significant letter by George Washington or Abraham Lincoln, for example, goes for an average of $20,000.

Napoleon presents an interesting dilemma for collectors. Although he signed many documents, his signature changed so often (at least 26 different ones, from “Bonaparte” to “Np”) that examples are worth less than Washington’s or Lincoln’s: $2,500 for a good signature on a letter of average military interest. Prices for famous American commanders can vary widely. In general, addressed envelopes (without a letter) by someone of importance but with no autograph are far less expensive than letters or historical documents themselves.

In the 20th century, many documents were typewritten, with added notes and signatures in famous hands. Another medium, the postcard, can be collected for far less cost. World War I has traditionally been less popular than World War II in the United States, since American involvement in the first lasted for only a year. Small military notes and typed documents from lesser-known American generals sell for less than $100—while the Red Baron’s signed photo goes for about $300. For World War II documents, the signatures of famous generals such as Dwight D. Eisenhower and Douglas MacArthur go for about $100.

The German Third Reich is a popular area of collecting—and forging—right down to faking the green pencil that Field Marshal Erwin Rommel used in his letters while in North Africa because the desert air dried ink too quickly. American GIs unwittingly helped the forging process by bringing home reams of Nazi stationery as souvenirs. Signed photos of German war heroes—real or forged—are quite abundant.

One area overlooked for years involves the personal diaries or journals of common soldiers in the Civil War. The longest and most descriptive accounts of battles often came from them—not from busy officers who had less time to write. Cheap diary books were sold in camp to soldiers. These diaries, ruled tablets in slate-colored leather, still turn up frequently in flea markets. In the mid-1960s, such diaries were sold by the basketful for a couple of dollars each. They are worth many times that now. Unfortunately, most Civil War diaries were written in pencil and have faded significantly with time.

As collectors have demonstrated, the written word is as much a part of history as the great events defined by them. Besides going online for dealer sites, would-be collectors of autographs and manuscripts might want to consult The Pen and Quill, the journal of the Universal Autograph Collectors Club, and Autograph magazine.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments