By William E. Welsh

The rain poured in sheets as the long column of French troops snaked its way through the Apennine Mountains of southern Italy along roads washed out by heavy rains. The soldiers shouted to be heard over the driving rain. Sickness and hunger had thinned the ranks. Wagons laden with supplies had been abandoned along the route by soldiers who barely had the strength to walk or ride their horses, much less steer a wheeled vehicle over the unforgiving hills.

The commander of the army, Count Charles of Anjou, admonished his officers to keep the men moving. Pope Clement IV had called for a crusade to liberate the Kingdom of Sicily from its Hohenstaufen ruler, Manfred, who was in the pope’s words, one of “a poisonous brood of a dragon of a poisonous race.” The dragon was a reference to Manfred’s father, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, who had conquered all of Italy against papal wishes and established his primary residence in southern Italy.

Charles was determined not to give up without bringing the enemy to battle. The youngest brother of French King Louis IX had waited his entire life for just such an opportunity, and the elements were not going to stop him. By sheer force of will he kept his army together. If he could bring that will to bear in battle, his army would conquer one of the wealthiest kingdoms in Western Europe.

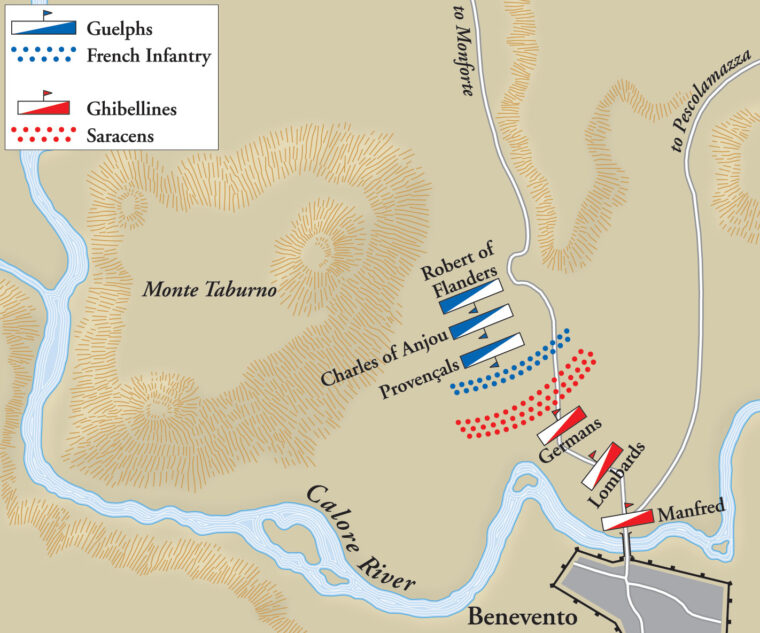

While Charles led his troops through the mountains, Manfred’s scouts informed him of the French army’s location. The Hohenstaufen ruler shifted his army from Capua to Benevento on the Calore River. There Manfred waited for the French in a strong position. Manfred had 3,200 heavy cavalry and 3,000 Saracen foot archers to fight Charles’s 3,000 heavy cavalry and 500 dismounted crossbowmen. What was at stake was far more than papal politics. The outcome of the Battle of Benevento would reverberate across the Christian world and alter the course of Mediterranean history.

To understand why the Kingdom of Sicily was such a prosperous realm by the mid-13th century, it is necessary to go back to a time when it was not unified. By the end of the 10th century, southern Italy was divided among several peoples. The Saracens held Sicily, the Byzantines controlled Apulia and Calabria, and the Lombards ruled the duchies of Benevento, Capua, and Salerno. The Byzantines and the Lombards lacked good troops to protect their realms, and so they hired large numbers of Norman mercenaries. Eventually the opportunistic Normans seized power for themselves.

In 1130, Norman noble Roger II was crowned King of Sicily. The Kingdom of Sicily, known as the Regno di Sicilia, or simply the Regno, encompassed all of southern Italy as well as the island of Sicily. During Roger II’s rule, the Normans established a stable theocratic government similar to the Byzantine Empire. Like the Byzantine model, one of the hallmarks of the Regno was that it boasted an efficient bureaucracy in which taxes were collected regularly. Because of the efficient administration of the Regno, it became one of the richest kingdoms in Europe.

Constance of Sicily, the wife of Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI of the House of Hohenstaufen of Swabia, inherited Sicily in 1194. Through his marriage, Henry VI became ruler of the Regno, and when he died in 1197, his young son Frederick II inherited the kingdom with his mother serving as the regent.

Roger II had ruled the Regno as a vassal of the pope, but Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II had no interest in serving the pope. During his reign as emperor, Frederick controlled Germany and most of Italy. A highly educated statesman and crusader, Frederick found Italy more to his liking than Germany. When Frederick was not campaigning abroad, he resided in the Regno. Despite the efforts of Pope Gregory IX, who openly waged war against him in Italy, Frederick made lasting changes to the Regno, such as establishing an absolutist monarchy and codifying a set of laws that would last for nearly 500 years.

Frederick’s son Conrad IV succeeded his father as ruler of the Regno in 1250. A new pope, Innocent IV, initiated efforts to find a prince in western Europe with sufficient resources to crush the Hohenstaufens and rule the Regno under papal guidance. One of the primary candidates to emerge for that cause was Count Charles of Anjou. But when approached by papal envoys in 1252, Charles politely declined the offer because of the objections of his eldest brother, French King Louis IX, who considered Conrad the rightful heir. Louis advised Charles not to get involved in the heated feud between the papacy and the Hohenstaufens.

But Conrad’s rule was short lived. Conrad, who had moved from Germany to Italy in 1252, was unable to acclimate himself to the subtropical climate of southern Italy. He died of malaria on May 21, 1254.

Conradin, Conrad IV’s son, was only two years old when his father died. Because he was so young, Conradin needed a regent to rule on his behalf. Manfred, who was Conradin’s half brother and an illegitimate son of Frederick II, actively sought the post. Manfred’s mother was Bianca Lancia, Frederick’s Italian mistress.

Manfred, who possessed great physical beauty and charm, had been raised in the Regno. Frederick’s will stipulated that Manfred should inherit the Regno should all other legitimate heirs die before him. Both Pope Innocent IV and Duke Louis II of Bavaria, Conradin’s uncle and guardian, agreed to let Manfred rule the Regno until Conradin came of age.

Manfred and Pope Innocent IV met shortly after Conrad died. The meeting was amicable, but after they parted Innocent tried to have Manfred assassinated. The attempt failed, and Manfred immediately set about expanding his power beyond the borders of the Regno.

At the time, Italy was divided into two political camps. The Ghibellines were loyal to the Hohenstaufens, while the Guelfs were loyal to the pope. Manfred mobilized a wide array of military forces that had served under his father. These forces included German knights living in Italy, Saracen troops residing in a colony at Lucera in Apulia, and various Ghibelline troops throughout Italy.

Pope Innocent died on December 7, 1254. His successor, Pope Alexander IV, continued the quest to find a prince powerful enough to unseat Manfred, but he also failed. Alexander, who died in 1261, was succeeded by Pope Urban IV, who continued the search begun by his predecessors.

Manfred eventually grew tired of being Conradin’s regent. He wanted to be the king of Sicily. He spread a rumor in the summer of 1258 that Conradin had died and, on August 10, 1258, Manfred had himself crowned king of Sicily. When the truth was learned that Conradin was alive and well, Manfred refused to step down. Manfred also arranged in 1258 for the engagement of his daughter Constance to Prince Peter of Aragon, which would ensure that Manfred had a powerful ally outside Italy. Four years after their engagement, Constance and Peter were wed.

Returning to the mainland after his coronation in Palermo, Manfred began a slow but steady conquest of central and northern Italy. By the time Pope Alexander died on May 25, 1261, Manfred and his allies controlled most of Italy except for the Venetian Republic and Rome. Pope Alexander’s successor, Pope Urban IV, was not intimidated by Manfred. Urban immediately resumed the continuing quest for a prince to dethrone Manfred. While Manfred was spending his days hunting in the forests of Apulia, Urban offered the Sicilian crown to Charles in 1262 provided he agreed to certain conditions.

Charles once again asked his older brother, French King Louis IX, if he could accept the offer. This time King Louis approved the agreement because he regarded Manfred as a usurper. When Charles accepted the offer, Pope Urban had it declared a crusade.

The principal terms of the agreement between the papacy and Charles were that Charles should pay an annual tribute to the Holy See, rule the Regno under papal suzerainty, and refrain from conquering any parts of Italy that lay outside of the Regno.

Charles was the youngest son of French King Louis VIII and Queen Blanche of Castile. In 1246, at the age of 20, Charles married Beatrice of Provençe, inheriting the County of Provençe, which was part of the Holy Roman Empire. To further enhance his prestige, King Louis IX gave Charles the counties of Anjou and Maine shortly afterward.

Charles was a large and imposing person, and he also was an experienced military commander. His personality was the exact opposite of Manfred’s. Whereas Manfred was warm and congenial, Charles was cold and aloof and almost never smiled.

The Count of Anjou was well qualified for the job the Papacy had in mind for him. He had been taught the ways of war from a young age, first at the court of his older brother Robert I of Artois, and afterward at the court of another brother, Alphonse of Poitou. Charles and his three older brothers participated in the Seventh Crusade to Egypt, where the Christians hoped to establish a base from which to eventually liberate Jerusalem. In heavy fighting against the Ayyubid Muslims in February 1250, Charles proved himself capable of successfully leading units in battle.

When the Saracens attempted to outflank the Crusader position opposite Mansurah, Charles personally led a successful counterattack. One of the four brothers, Robert, died in the Battle of Mansurah. When the Saracens switched to the offensive, Charles was able to hold his position on the Crusader left flank while the right flank was driven back. The crusade ended disastrously in April 1250 when the crusaders were forced to surrender. Louis, Alphonse, and Charles eventually were ransomed and returned to France.

Pope Urban, who died on October 2, 1264, did not live to see Charles invade the Regno. His successor, Pope Clement IV, who hailed from Languedoc, had worked closely as a cardinal with the French royal family. Clement unequivocally supported Charles’s quest to oust Manfred from the Regno.

To help fund the crusade, Pope Clement ordered the churches in France to give one-tenth of their tithes to Charles over a three-year period. The tithes enabled Charles to offer decent wages to knights and crossbowmen recruited in France and Flanders for the crusade. Financing the crusade ultimately would prove more expensive than either Pope Clement or Charles anticipated, and both had to borrow heavily to generate additional funds.

Charles moved to Marseilles in 1264 to prepare to lead the crusade in Italy. While Charles prepared for the crusade throughout winter 1264-1265, Pope Clement ordered monks to spread word of the crusade throughout France, Flanders, and Italy.

Charles planned to sail to Rome in the spring of 1265 with his household troops. The main army, which was assembling at Lyons, would follow by marching overland. Since Tuscany was firmly held by Ghibelline troops loyal to Manfred, the army planned to march to Rome via Lombardy and the Papal States. Even if the army had to fight its way through some parts of Lombardy, Charles believed it would suffer fewer losses by that route than if it was forced to fight a major battle in Tuscany.

Charles embarked from Marseilles on May 10, 1265, with 300 household troops and arrived 10 days later in Rome. Pope Clement, who felt at risk in Rome from attack by Ghibelline forces, resided in the Umbrian town of Perugia. When Manfred learned that Charles had arrived in Rome with nothing more than his personal retainers, he quipped, “The bird is in the cage.”

To Manfred’s shock, Charles was greeted with open arms by the people of Rome. The defection of a number of Ghibelline leaders in Lazio and Campagna was a bad omen for Manfred. On June 28, group of cardinals crowned the 39-year-old French count as the new king of Sicily.

The coronation stirred Manfred to action. He led a hastily assembled Sicilian army from Abruzzo and marched on Rome. Charles marched out to meet him. Charles established a strong position at Tivoli. The location, 20 kilometers east of Rome, was close enough for Charles to receive Guelf reinforcements from in Rome if necessary. When Manfred reached Arsoli, he sent some troops to assess Charles’s position at Tivoli. Minor skirmishing ensued, but Manfred withdrew rather than attack Charles in a strong defensive position. His withdrawal resulted in the further erosion of Ghibelline support throughout Italy.

The main French army left Lyons in the first week of October 1265. The army comprised 6,000 mounted knights and sergeants, 600 mounted crossbowmen, and 5,000 foot soldiers, some of whom were professional crossbowmen. About one quarter were from Provençe, and the rest from Anjou, Maine, Champagne, Picardy, and Flanders. Guy of Mello, Bishop of Auxerre, was the overall commander of the army, and his chief lieutenants were Giles le Brun, Constable of France, and Hugh Mirepoix, Marshal of France. The principal divisional commanders were Count John II of Soissons, Count Bouchard V of Vendôme, Philip of Montfort, Guy of Montfort, and Robert of Flanders.

The French army marched through Nice and crossed into Piedmont via the Tenda Pass on a road laid out in ancient times by the Phoenicians. Once in the Piedmont, the army traversed friendly territory ruled by the Marquis of Monteferrat. When the French reached the town of Asti, they learned that Ghibelline troops loyal to Manfred, who were under the command of Marquis Oberto Pallavicini, occupied a string of towns blocking their passage through the Po Valley.

The weakest link in the cordon of enemy-held towns was Vercelli, which lay north of Asti. When the townspeople of Vercelli learned that the French were approaching, they revolted against the Ghibellines. This enabled the French to pass through the town without incident. The French also were able to pass unhindered through Milan.

As the French continued marching east through the Po Valley, they learned that the Ghibelline governor of Cremona had deployed his troops at Soncino, blocking the easiest crossing of the Oglio River. The Bishop of Auxerre offered the governor a bribe, which he promptly took, and the French continued east.

More difficulties were encountered when the French attempted to cross into Mantua. When the French approached the Chiese River, they found another small Ghibelline army blocking their path. But the French contacted friendly Guelf troops in Mantua for assistance. The Mantuan Guelfs subsequently attacked the Ghibellines from the rear, forcing them to retire. The French continued from Mantua to Bologna, whose townspeople were friendly to the French since their town was located within the Papal States.

From Bologna, the French marched south to Ancona on the Adriatic Sea, where they received much needed supplies that Pope Clement had stockpiled for them. From Ancona, the Bishop of Auxerre led his troops west across the Apennine Mountains to Rome. After 31/2 months of hard marching on a circuitous trek of nearly 1,500 kilometers, the army marched into the city on January 12, 1266.

Pope Clement was very pleased when informed that the French army had reached Rome safely without having to fight any major battles. The cost of keeping the army supplied on its march was exorbitant. Charles’s wife Beatrice had pawned her jewels at the outset of the expedition. French King Louis was considering a new crusade to Africa, and for that reason declined to loan Charles money, but Charles’s brother Alphonse offered a sizable short-term loan.

Charles applied to various Florentine and Sienese banking houses for additional funds but was only able to raise enough to pay the expenses of his army for one month. For his part, Pope Clement pledged the treasure and plate of the papal chapel to secure an additional loan. Both Charles and Clement were heavily in debt, which forced Charles to order his troops to prepare to leave Rome after just eight days of rest. The army would be marching in winter, which is the wettest time of year in southern Italy. The French army faced a difficult march through unfamiliar territory with very little forage available for the army’s horses and pack animals.

The French army departed Rome on January 20, 1266, marching south on the Via Latina to the border of the Kingdom of Sicily. Manfred had ordered the Ghibelline garrison at Ceprano on the Regno’s border to delay the French as long as possible while he assembled a large army to meet Charles in battle. When the French reached Ceprano, they encountered no resistance and were astonished to find the bridge over the Garigliano River intact.

The most significant resistance the French army encountered from a Sicilian garrison occurred at San Germano, which was situated on Monte Cassino near the monastery where the Benedictine order was founded in the early 6th century. A large garrison of Saracens devoutly loyal to Manfred occupied the double-walled fortress replete with projecting circular towers and 11-foot-wide curtain walls. Charles did not want any sizable Sicilian forces in his rear, so the French camped outside the stronghold’s walls and deployed their siege engines.

On February 10, a group of Saracen sentries made a small sortie from a gate in the outer wall to try to capture several French valets drawing water from a spring. The sortie, which was made to capture prisoners for interrogation, went badly awry when the cries of the valets brought a quick response from French troops under Bouchard of Vendôme, who were encamped in that sector. The clash escalated rapidly, and during the confusion some of the French soldiers were able to fight their way through the gate and secure it for reinforcements who poured through the gate behind them. The error proved to be the garrison’s undoing, and it had no choice but to surrender.

While the French were steadily reducing the garrisons in their path, Manfred was assembling an army at Capua just south of San Germano. In an effort to assemble a host that would heavily outnumber the advancing French army, Manfred also sent word to his cousin, Prince Conrad of Antioch, who had been left in charge of Sicilian forces in Abruzzo, to immediately come to his aid. While he awaited Conrad’s arrival, Manfred deployed his army at Capua in a strong position behind the Volturno River.

While the French were mopping up at San Germano, Charles sent scouts south to ascertain the whereabouts of Manfred’s army. After several days on the road, they returned and informed Charles that the fortified bridge across the Volturno River at Capua was strongly held but that there were several fords upstream left unguarded. Charles decided to march into the Samnite Apennines, cross an unguarded ford of the Volturno, and fall on Manfred’s right flank.

The French army departed San Germano on February 15, marching southeast into the mountains. A march that in summer might have taken only two or three days became an arduous 10-day trek. Charles underestimated the difficulty of marching through mountain passes where the army had to cross numerous hillside streams overflowing their banks from heavy seasonal rains. The French army managed to cross the Volturno despite the high water and make its way to Telese in the Calore Valley.

The French had been forced by that point to abandon most of their wagons and carts and to continue with just their horses and pack animals. By the time the French reached Telese they had exhausted food staples such as flour and were reduced to eating some of their pack animals. The situation worsened even further when some of the French horses died in the mountains from lack of forage.

Charles had been informed by his scouts before he reached Telese that Manfred had anticipated his flank march and shifted east to take up a more secure position. Having a good road and a shorter distance to cover, Manfred had with little difficulty switched his base of operations to Benevento.

On the afternoon of February 25, the French troops marched past the steep limestone folds of 4,500-foot Monte Taburno on the west side of the Calore Valley. At last, from the top of a ridge, the French spied Benevento in the distance. To their immediate front, the ridge sloped down to the Plain of Grandella, which lay on the north bank of the Calore River. A single bridge, which was very wide, led from Benevento on the south bank to the plain on the north bank. The Sicilian army, well fed and well rested, was camped on the south bank of the Calore awaiting the arrival of the starving French.

A few days before the arrival of the French, Manfred had addressed the local nobility and ecclesiastical authorities. In a rousing speech, the Hohenstaufen bastard implored them to resist their would-be conquerors.

“A fire which has long been burning in the distance has approached with the rapidity of lightning,” said Manfred. “A danger which seemed only to arouse futile talk now threatens to overwhelm us unless we unite together to resist it. A hard heart, a gloomy disposition, an unbending will leads these troops, and they are not inferior to their commander in cruelty and greed for gold and blood. The sole object is to make you forget all you owe to my father and his house, and to force you, a free people, to accept a foreign ruler unworthy of you. [Let us] teach this foreign, ambitious, and greedy people that they cannot treat the kings, realms, and people of our beautiful Italy according to their wicked will.”

Although he made a major effort to enlist the support of the local people in resisting the French, Manfred had a great sense of uneasiness when the French arrived on the opposite bank of the Calore. The lack of resistance shown by the Ghibelline garrisons posted along the French line of march, with the exception of the Saracens at San Germano, led Manfred to believe that the Ghibelline captains in his ranks would give only a half-hearted effort during the approaching battle.

Although an additional 800 German heavy cavalry had arrived just a few days earlier to boost the size of his army, Manfred still had no word of the approach of Conrad of Antioch. Manfred decided to act without waiting for his cousin for two important reasons. First, he believed that the Ghibelline allies with him at Benevento might abandon him or even switch sides the longer he waited. Second, his scouts had informed him of the weakened condition of the French army as a result of its forced march through hostile country. Some of Manfred’s captains urged him to wait for Conrad of Antioch to arrive before offering battle, but Manfred did not heed their advice.

Even Charles was concerned about the condition of his army. In a dispatch to Pope Clement sent the night before the battle, Charles told the pontiff that the French knights’ war horses might perform poorly in the coming battle because of fatigue and hunger. But the French army was on the verge of starvation; the only way it would survive was to win a pitched battle against Manfred’s well-rested troops.

At dawn on February 26, Charles gave a rousing speech to his captains and knights. “The long wished for day of battle has at last dawned, and we must now conquer or die,” Charles said. “Better to die in battle, honorably and together, than miserably, singly, in disgraceful flight. Fear not your foes! We fight, as good Christians, in a hallowed cause, and blessed by the church; they are of other creeds, bowed down to the earth by the weight of their guilt, and doomed to eternal perdition.”

After the speech, Charles ordered trumpets sounded to assemble his troops for battle. The French benefitted from an initial advantage in terrain as the Sicilian army would be attacking uphill from the river, which occupied the lowest point in the valley, across the Plain of Grandella.

While the French were assembling on the slope of a ridge at the north end of the Plain of Grandella, a long column of Saracen foot archers began crossing the Calore. Once the 3,000 Saracen foot soldiers were across the bridge, they deployed into a line of battle and began to advance toward the French. Charles was greatly relieved to see the Sicilian vanguard advancing to meet him. This meant Manfred had decided to attack first. The upshot was that the French would not have to undertake the difficult task of forcing a crossing of the Calore.

The Saracens were armed with composite bows that could fire light arrows up to 400 yards. These arrows posed no real danger to the heavily armored French knights because they could not penetrate their mail, but the arrows were capable of killing the French crossbowmen and also maiming the French cavalry’s horses. Advancing as skirmishers, the Saracen archers’ task was to win a missile contest with the French crossbowmen and then shower the French cavalry with arrows, killing their horses and, if they were lucky, also killing some of the men. Once the Sicilian cavalry advanced, the Saracens were to pass through their ranks and redeploy behind them to kill with their daggers any enemy cavalry that were unhorsed.

While the Saracens were engaged with the French crossbowmen, Prince Galvano Lancia of Salerno, who was Manfred’s uncle, led 1,200 German heavy cavalry across the bridge. While the French cavalry were clad in mail armor, the Germans were wearing coats-of-plate armor designed to offer superior protection over their torsos.

Waiting to follow behind the Germans was a second division of cavalry consisting of 1,000 knights and sergeants from Lombardy led by Count Giordano of Anglona, who was marshal of the Sicilian army. At the rear of the army, serving as its reserve, was the third division composed of 1,000 Sicilian cavalry led by Manfred.

Manfred did not trust the Sicilian knights and sergeants, and so he stationed himself with them to ensure that they followed his orders and did not switch sides or desert him once the battle was under way. In particular, Manfred distrusted his cousins Count Richard of Caserta and Count Thomas of Acerra. Manfred’s closest friend, Tebaldo Annibaldi, also was deployed in the third division to help monitor the Sicilian nobles’ actions.

The French army that arrived before Benevento had been reduced in manpower by about 50 percent from its original strength. This was due to hunger, losses in small actions, and the detachment of large numbers of foot soldiers to guard captured towns and castles. Charles ordered the 500 dismounted crossbowmen who remained with the army to deploy in front of the cavalry to counter the Saracen archers.

Hugh of Mirepoix led the French first division, which was composed of 900 Provençal cavalry. Assisting Mirepoix by leading a portion of the first division was veteran commander Philip of Montfort. Charles commanded the second division, which was made up of 1,000 French cavalry. Other key captains leading parts of the second division were Guy of Mello, Count Bouchard of Vendôme, and Simon of Montfort.

Giles le Brun led the third division, which consisted of 700 French and Flemish cavalry. A fourth division, composed of 400 Italian cavalry, was under the command of Florentine Guelf Guy Guerra. Behind the fourth division was a small number of lightly armed infantry who did not possess crossbows. Their job was to follow the cavalry and assist friendly cavalry who had been unhorsed to remount, as well as capture or kill any enemy cavalry that had been unhorsed.

For some unknown reason, the Saracens did not wait for Manfred’s order to advance but did so on their own initiative. They yelled loudly as was their custom when they marched into battle to strike terror in their opponents. But the French crossbowmen were professionals. It would take more than yelling to force them to retire from the front.

The archers from both sides soon were engaged in a duel to the death. The French crossbowmen were overpowered not only because of their fewer numbers, but also because of their slow rate of fire. In a short time the casualties among the French archers were so great that the survivors broke off the action and fell back toward the safety of the cavalry.

Seeing the rout of his crossbowmen, Charles sent an order to Mirepoix to lead his Provençal horsemen in a charge meant to rout the Saracen infantry. Just the sight of the Provençals riding swiftly downhill compelled the Saracens to fall back. Those who were too far forward to escape were trampled by the Provençal cavalry.

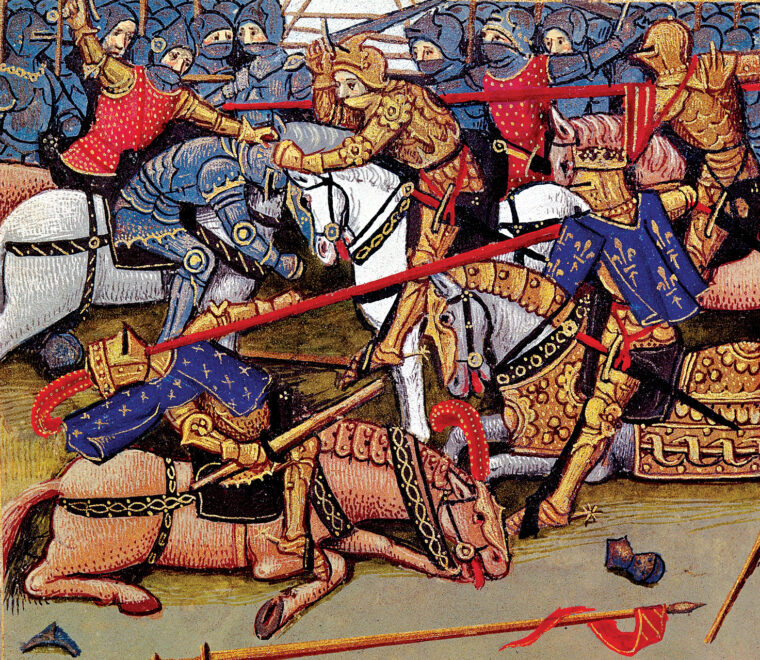

Lancia, who hoped to stabilize the situation and buy time for the rest of the Sicilian army to deploy on the north bank, also attacked without orders. The double rank of German cavalry advanced at a trot with their boots nearly touching so that the French could not penetrate their formation. When the German and Provençal cavalry collided, the clangor of steel swords echoed in the hills and was heard clearly by the townspeople of Benevento, who were feverishly praying for salvation from the invaders.

The coats-of-plate armor worn by the Germans stood up well against French weapons. One of the advantages of the new armor was that it withstood anything but the most well-directed thrust of a lance or sword. Dismayed at the seeming invincibility of the Germans, the Provençals were steadily driven back up the slope toward the French camp.

The Provençals neither panicked nor tried to flee the German juggernaut. The Provençals had complete faith in their commanders. Both Mirepoix and Philip of Montfort, who were fighting on different parts of the front line, shouted encouragement to their knights and sergeants who continued to try to crack the German battle line even as they were driven steadily back.

While the Provençal cavalry was fighting desperately against the Germans, Charles ordered the 400 Guelf horsemen in the fourth line to join his division, which he was preparing to lead into battle. Once the Guelf horsemen had joined his line, Charles led his division into the fight. When the second French division joined the melee, the din was terrific as hundreds of horsemen fought in a grand melee in which both sides sought to infiltrate the ranks of the other. Lances shattered, swords bit into flesh, and maces clanged when they landed on helmets.

The veteran German knights and sergeants, who had fought in all kinds of actions from the icy shores of the Baltic to the turquoise waters of the Mediterranean, initially managed to hold their ground despite being outnumbered nearly two to one. At some point in the fighting, one or more French knights observed that when the German cavalry raised their heavy swords to strike a gap in their armor was visible underneath their arms. As French horsemen regrouped to attack, they shared the discovery with others. When Charles learned of it, he shouted to those around him: “Thrust with the point; stick them with it!”

The French knights used the points of their swords and their daggers to stab the Germans in their armpits whenever the Germans raised their arms to wield their heavy swords. The French also began to plunge their swords into the flesh of the German horses, an act that violated the code of chivalry.

Soon casualties among the Germans began to mount, which resulted in gaps in their tightly packed ranks. Once this occurred, the French horsemen began crowding the German cavalry so that the latter could not make effective use of their heavy swords. At some point in the crush of cavalry, Salerno was killed.

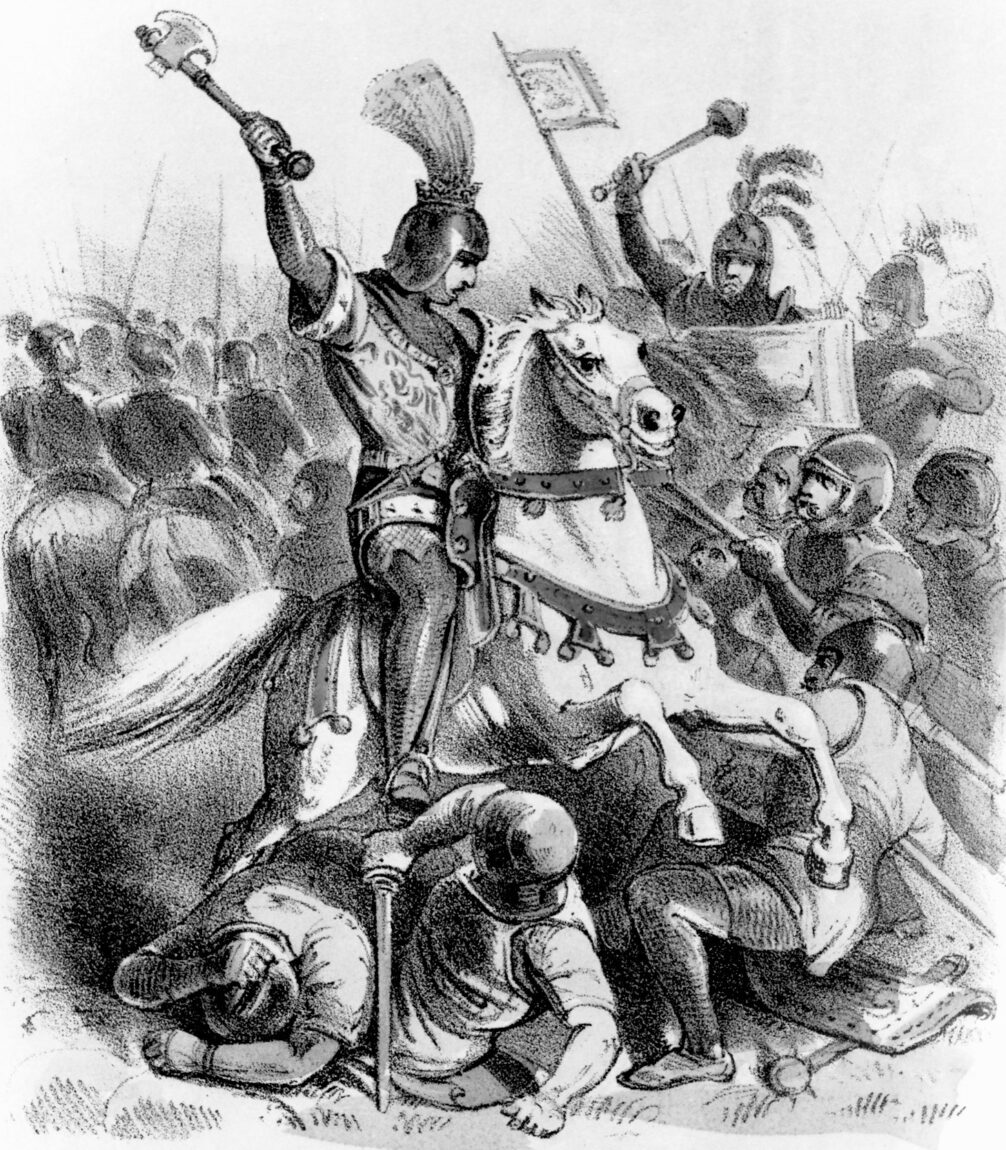

By that time the remainder of the Sicilian army was across the Calore. Manfred had been holding back the rest of his cavalry, whose allegiance he questioned, on the possibility that the crack German cavalry might actually be able to drive the French cavalry from the field. But when Manfred observed the German cavalry waver as a result of being heavily outnumbered, he sent a messenger to Anglona with instructions to go to the aid of the Germans.

By the time Anglona’s troops joined the fight, the Germans had been routed. What the Lombards encountered were two divisions of French cavalry waiting for them. The Lombards charged into the French line but could not break it. At just the right moment, Charles ordered Le Brun to lead the third division into battle. The fresh division swept around the flanks of the Lombards and attacked them from behind. Assailed from front and rear, the Lombards fled toward the Calore. Anglona tried in vain to rally them but soon gave up to save himself.

After his second division had gone forward, Manfred exchanged surcoats with Annibaldi so that when Manfred joined the battle the French would be deceived as to his exact location. This ruse concealed the commander from the enemy, reducing the likelihood that he would be slain and his troops become demoralized as a result. The deception was an approach adopted by a small minority of medieval commanders.

When the Lombard cavalry was routed, Manfred prepared to lead his division into battle. But the Sicilian nobles in the third division had no intention of participating in a battle they felt already had been lost. They led their troops toward the Calore Bridge in the hope that they could reach the relative safety of Benevento.

But Manfred had no intention of quitting the fight. Knowing that he was riding to his death, Manfred ordered his household troops to follow him forward. They had taken an oath to guard their king no matter what the odds. Annibaldi, still wearing Manfred’s surcoat, also joined the doomed attack.

From their vantage point on higher ground, the French troops watched as several dozen heavily armored Sicilian knights, one of whom wore a surcoat with a black eagle on a yellow background indicating he was the king of Sicily, charged toward them. As they closed with the French, the attacking troops shouted, “Hurrah for Swabia!” The French cavalry braced for the shock of the charge. The final clash did not last long. Both Manfred and Annibaldi were slain, as were all of Manfred’s household troops.

After Manfred and his bodyguard had been cut to pieces, Charles ordered his troops to pursue the remnants of the Sicilian army. The panicked Sicilian troops swarmed onto the bridge in an effort to escape the French. Many plunged into the Calore, preferring to drown rather than be butchered by the French. Only about 600 of the 3,200 Sicilian cavalry managed to elude death. Those who escaped the French did not seek haven in Benevento but fled into the hills to the south of the city. With no one to stop them, the French sacked the city.

For two days the French searched the battlefield but could not find Manfred’s body. On the third day after the battle, a soldier found a naked body believed to be Manfred. The man brought the body to Charles, who ordered Anglona, who had been taken prisoner by the French, to identify the body, which he did.

Manfred’s body initially was buried near the Calore Bridge, but Pope Clement ordered the body exhumed and reburied on the north bank of the Garigliano River outside the Regno. The reason for that was to show that Manfred, who Clement believed had usurped the throne, did not deserve to be buried in the Regno.

On March 7, the French marched into Naples. Although Charles imprisoned Manfred’s wife and children, he granted amnesty to all the troops who had served under Manfred. Shortly after his arrival in Naples, Charles sent Philip of Montfort with a small army to secure the island of Sicily.

Charles’s quest to conquer the Regno did not end with the occupation of Naples and Sicily. Two years later, Charles fought 16-year-old Hohenstaufen prince Conradin, who came south from Germany with a large army to try to take back the Regno from Charles. Although outnumbered, Charles’s superior generalship enabled him to defeat Conradin at the Battle of Tagliacozzo, which was fought on August 23, 1268. Conradin, who was taken prisoner, was executed two months later.

In the years following his impressive battlefield victories in southern Italy, Charles established a small empire in the central Mediterranean. While he was busy expanding his sphere of influence into the Balkans, the Sicilians revolted in March 1282 against French rule, slaughtering several thousand French officials and residents.

The rebellion initiated the War of the Sicilian Vespers, which lasted from 1282 to 1302. The war pitted Peter III of Aragon, the protector of the Sicilians, against Charles, who was backed by his relatives in France. Charles’s rule over the Regno suffered a major setback on June 5, 1284, when his Provençal navy was soundly defeated by the Aragonese navy. Charles died the following year. Through the Peace of Caltabellotta in 1302, the Regno was divided between the Aragonese, who retained control of Sicily, and Charles’s son, Charles II, who retained southern Italy, which became known as the Kingdom of Naples.

Charles of Anjou’s conquest of the Regno had been sanctioned by the papacy. Not content with ruling the Regno, Charles continued his war of conquest in eastern Europe. Charles of Anjou’s insatiable thirst for wealth and power ultimately brought about the dissolution of the Regno and tarnished his legacy as well.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments