By Arnold Blumberg

The column of Confederates marched east as quietly as possible along the bed of an unfinished railroad that knifed through the Wilderness south of the Rapidan River shortly before midday on May 6, 1864. When the head of the column reached a point perpendicular to the left flank of the Union Army, the staff officer leading the four Confederate brigades halted the column. That was a signal to the officers in the brigades to have their troops face north and prepare to advance swiftly through an emerald ravine toward the unsuspecting enemy.

Echoing in the head of Chief of Staff Lt. Col. G. Moxley Sorrel were the last words First Corps Commander Lt. Gen. James Longstreet had said to him before Sorrel departed with the flanking column. “Hit hard when you start, but don’t start until you have everything ready. I shall be waiting for your gunfire, and be on hand with fresh troops for further advance.”

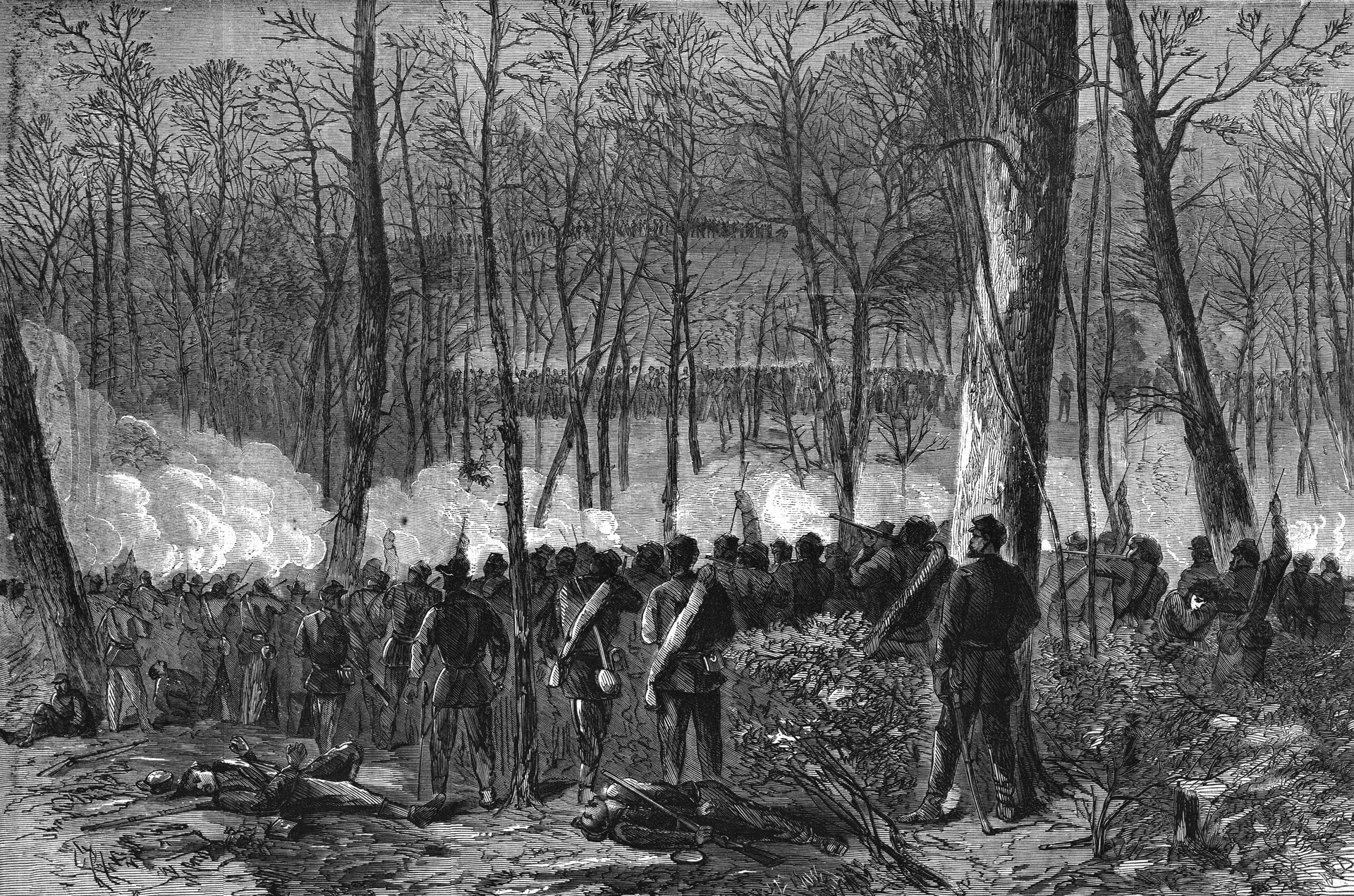

Rebel officers up and down the line waved their men forward with their swords. The troops stepped off with the determination of soldiers who knew they had a decisive advantage over their foe. A short time later, screaming at the top of their lungs the blood-curdling rebel yell, the graybacks fell on soldiers of Maj. Gen Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps resting during a lull in the action.

The result was predictable. The startled bluecoats began a general stampede in search of safety. Some were shot trying to raise their rifles, while others were struck in the back by bullets as they ran for their lives. Resistance was useless. In some places, clusters of Yankees tried to make a stand, but they were quickly encircled and slain or captured as the flood of Rebels swept through the woods south of the Orange Plank Road. In less than an hour’s time, the Confederates had routed more than twice their number.

When Sorrel reached the Plank Road, he saw Longstreet and his staff riding toward him from the west. All were exuberant about the success of the attack. But soon the discussion turned to how the First Corps might build on its initial success. After it was decided to launch a similar attack on the new Federal position being established farther east, something catastrophic happened to upset those plans.

As the 1864 campaigning season in Northern Virginia neared, General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, finalized his plan to confront the inevitable advance of his perennial opponent, the Union Army of the Potomac. The “Old Gray Fox” fervently desired that the Union Army, when it crossed the Rapidan River and moved to his east in a bid to reach the Southern capital of Richmond, would traverse what was called the Wilderness. The 70 square miles of densely tangled second growth, stunted pine trees, and thick undergrowth of bushes and vines greatly constricted the movement of armies and made it impossible to deploy troops for battle in neatly aligned ranks.

One Confederate who fought there described it as “a jungle of switch, 20- or 30-feet high, more impenetrable, if possible, than pine.” While many a Rebel and Yankee soldier complained about the difficulty of maneuvering in such vegetation, Lee realized that a battle in such flora was to his immense favor.

The Wilderness gave Lee the advantage of neutralizing the strengths of the Federal army. The size of his force was 52,000 infantry, 8,000 cavalry, and 224 pieces of artillery. In contrast, the Union host initially participating in the Wilderness Campaign numbered 105,000 foot soldiers, 12,000 mounted troopers, and 274 cannons.

A fight in open terrain gave the Union the potential to mass more infantrymen than the Southerners could bring to bear. In the Wilderness, however, where movement and visibility were very limited, the opportunity to bring a larger force in position to fire or assault a smaller one was rare. The Army of the Potomac possessed more and better artillery than its Southern counterpart. Yet, the long arm needed an extended and clear field of fire to be effective; such conditions existed in very few areas in the Wilderness. The Union cavalry arm had, since June 1863, shown that it was now a force to be reckoned with. But in the Wilderness its numerical and weapons superiority would be negated by the wooded terrain, narrow roads, and limited open ground ideal for mounted action.

Keeping in mind all the advantages the Wilderness afforded him, Lee determined that his strategy for the coming fight would engage his enemy in the Wilderness. Lee would seek in the coming battle to avoid a general engagement until all his forces were at hand. Once all three of his corps had arrived, he would switch to the offensive and deliver a decisive blow. Confederate Second Corps chief of artillery, Brig. Gen. Armistead Long, noted that Lee felt confident that “there was reason to believe that his antagonist would be at his mercy while entangled in these pathless and entangled thickets, in whose thickets disparity in numbers lost much of its importance.”

Lee was not the only one who preferred to fight in the foreboding terrain of the Wilderness. Coincidentally, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, chief of the Army of the Potomac, also hoped the Wilderness would be the location of the impending battle. Although this miserable landscape was not Meade’s ideal place for a fight, he felt things could be worse. He feared that after his army crossed south of the Rapidan River Lee would move back to the strong defensive works at Mine Run, which the Confederates had occupied between November 26 and December 1, 1863. Meade fortunately did not assault that formidable position then, and doing so during the new campaign was something he wanted to avoid.

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, commander-in-chief of the Armies of the United States, accompanying the Army of the Potomac and its de facto battlefield commander during the previous year, wanted to come to grips with Lee’s force as soon as possible, and he was not particularly concerned about where that occurred. To make his desire clear, the aggressive Westerner, after taking up his new post, notified Meade on April 9, 1864, that “Lee’s army will be your objective point. Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.”

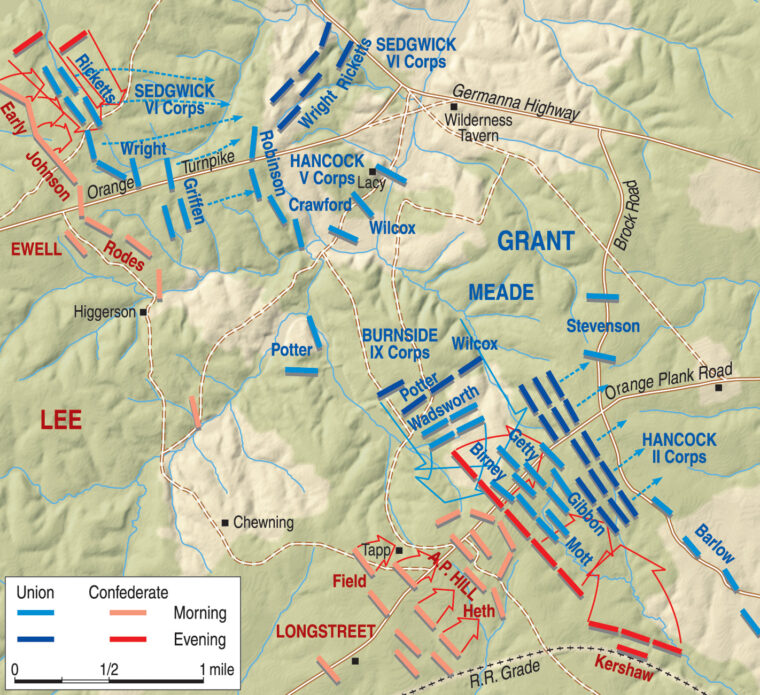

On the night of May 3-4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac moved eastward from its winter camp in Culpepper County, Virginia, and crossed the Rapidan River. Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s V Corps, with Maj. Gen John Sedgwick’s VI Corps following, passed over the river at Germanna Ford; five miles downstream Maj. Gen Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps waded across at Ely’s Ford.

Lee’s troops were at the time bivouacked west of the Wilderness. After learning on May 4 of the Federal move, the Confederate commander set his men in motion eastward on three parallel routes leading toward the enemy. Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Second Corps set out on the northernmost road, which was the Orange Turnpike; Third Corps (less Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson’s division) under Lt. Gen. Ambrose P. Hill, hurried along the Orange Plank Road (23/4 miles south of the turnpike); and four miles south of the Orange Plank Road Longstreet’s First Corps marched on the Catharpin Road.

On the morning of May 5, as the Army of the Potomac trudged through the Wilderness, Meade was informed of the approach of elements of the Army of Northern Virginia racing toward him from the west. Hoping to fight his gray antagonist at a place other than the Mine Run defenses, Meade cancelled his army’s marching orders for the day and ordered Warren to “halt his column and attack the enemy with his whole force.” When Grant heard of Meade’s decision to initiate combat he wholeheartedly endorsed the change in plans his subordinate had made. In a message to Meade at 8:24 am, Grant said, “If any opportunity presents itself for pitching in to a part of Lee’s army, do so without giving time for disposition.”

During the early hours of May 5, as both armies funneled troops toward the scene of impending action, the contest developed along two parallel roads: the Orange Turnpike and the Orange Plank Road. The Rebels marched eastward along both thoroughfares as the Yankees travelled westward. Lee’s units, in keeping with their commander’s goal of trying to delay the fight until the entire Army of Northern Virginia was concentrated, limited themselves to defensive operations. For the Army of the Potomac’s part, Meade ordered it to assail the enemy as quickly as possible, ignoring the need to form proper troop dispositions and alignment, both of which would have required much time to achieve due to the disagreeable Wilderness vegetation. Many of Meade’s subordinates, fearing the consequences of piecemeal attacks, delayed their assaults to form up proper attack formations, while others carried out their instructions to the letter.

In numerous instances, reluctant Federal officers sent their men stumbling though the woods toward an enemy whose position was unknown. On that first day of the battle in the Orange Turnpike sector, one substantial assault and two piecemeal efforts launched by Warren’s V Corps and Sedgwick’s VI Corps proved only limited successes. However, along the Brock Road-Orange Plank Road vicinity elements of Sedgwick’s VI Corps and Hancock’s II Corps drove back the Confederates of Hill’s Third Corps. Grant took this as a sign that the battle was on the right track and that when Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside’s IX Corps arrived the next day, the Federal Army would make an all-out attack along its entire front.

Lee also had designs for an offensive on the second day of the battle. By dawn on May 6, Lee expected the arrival of Longstreet’s First Corps via the Catharpin Road, which paralleled the Orange Plank Road to the south. Lee’s plan was for Ewell’s Second Corps and Longstreet’s First Corps to do the fighting. While the former continued to engage the enemy along the Orange Turnpike, the latter would shift north to the Orange Plank Road, relieving Hill’s men. Hill’s Third Corps, which had suffered greatly on May 5, was not expected to participate in any of the early morning fighting on May 6. Instead, it would serve as a second line across the Plank Road and be available for service later in the day.

Before sunrise on May 6, the Battle of the Wilderness was renewed with a push by Hancock’s Yankees forcing Hill’s beleaguered Confederates back farther westward from the intersection of the Brock and Orange Plank Roads. North of the road, connecting Hancock’s right with Warren’s V Corps, was Brig. Gen. James S. Wadsworth’s 4th Division of Warren’s V Corps. Soon after daylight, Longstreet’s troops, in the form of Maj. Gen. Charles W. Field’s and Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw’s divisions, entered the Orange Plank Road and approached the savage fighting that had commenced earlier between Hill’s and Hancock’s men. Upon its arrival along the Orange Plank Road at about 8 am, Anderson’s division was placed north of the road in reserve by Longstreet.

Around 6 am, after forming Field’s brigades to the north and Kershaw’s men to the south of the roadway, Longstreet sent his command forward. Longstreet and his staff followed on its heels to observe the attack. Major John Haskell, who commanded a Confederate artillery battalion in the Wilderness, noted that the 43-year-old corps commander was “always grand in battle [and] never shone as he did here.” Longstreet’s six-brigade attack force, which was tightly packed in columns preceded by heavy skirmish lines, struck Hancock’s disordered and weakened divisions along a narrow front, soon driving back the Union II Corps soldiers. Wadsworth’s men were battered into a horde of flying fugitives by three brigades of Field’s command.

By 8 am, after two hours of vicious fighting and having forced his opponent to withdraw over 200 yards, Longstreet’s thrust stalled. Thereafter, neither contestant could make headway against the other, and neither was willing to retreat. Unabated murderous exchanges of musketry ensued. The opponents were separated by mere feet, but invisible to one another due to the thick foliage of the Wilderness.

Meanwhile, to the north along the Orange Turnpike, Ewell’s graybacks hit the Union V Corps and VI Corps, preempting Grant’s planned operation in that area of the battlefield. By 10 am Grant’s planned grand offensive for May 6 was a dead letter, never to be resurrected.

Lee, however, was just getting started. Now with Longstreet and Anderson on the field and the situation along the Orange Plank Road stabilized, Lee was ready to launch his own major attack, and it did not take long before he learned of an excellent location to strike.

The graded right of way of an unfinished railroad ran west from Fredericksburg, passing two miles below Chancellorsville, then near Catherine Furnace, and crossing the Brock Road at Trigg’s Farm bending northwest and parallel to Brock Road for a short distance. As it neared the Orange Plank Road the unfinished railroad curved to the left and ran to the west continuing even with the Orange Plank Road a quarter of a mile below it.

The roadbed offered an excellent route for the movement of troops through the tortuous Wilderness terrain; it was a perfect path by which either side could gain its opponent’s southern flank and rear. Its existence was known to both armies before the battle started, but the savage fighting of the first day and that of the early morning of the second day prevented both sides from availing themselves of the opportunity to use it to envelope their enemy’s position. That would dramatically change as the noon hour of May 6 approached.

After Longstreet’s counterattack had come to a close, Brig. Gen. William T. Wofford, at the helm of a brigade in Kershaw’s division, First Corps, and occupying the extreme right of the Army of Northern Virginia’s front just above the railroad cut, sent out skirmishers to feel for the Federal’s left. The Rebel scouting parties discovered that the Confederate right was squarely opposite the enemy line’s southern end. Wofford sent back word to Longstreet describing how the unfinished rail line could be used to outflank the Yankees and requested permission to make such an attack.

The same information regarding the feasibility of a flank march around the Union left via the railroad cut was confirmed by the chief engineer of the Army of Northern Virginia, Maj. Gen. Martin L. Smith. While fighting raged on the Orange Plank Road, Smith, who had been assigned to Longstreet’s headquarters to aid in negotiating the Wilderness ground, had been ordered, whether by Lee or Longstreet is not clear, to search for a way around Hancock’s left. Cautiously moving to the railroad cut and then east along it, Smith realized that he had discovered the Union II Corps’ southern margin and that it was up in the air with not a bluecoated defender to be seen. Smith also noticed that a series of ridges extended northward from the rail bed to the Orange Plank Road. Between the ridges were natural depressions that were handy avenues leading directly to Hancock’s unprotected flank and rear.

At 10 am Smith returned from his reconnaissance and reported to Longstreet that the Federal line extended but a short distance beyond the Orange Plank Road. The enemy position was exposed and invited an attack from the railroad cut, he said. Here was the route Lee was seeking.

At Lee’s command post there was a consensus as to what was needed. The idea of a flank attack particularly suited Longstreet. Although he had gained great successes with devastating frontal assaults at Second Manassas, Gettysburg, and Chickamauga, and a few hours earlier in the Wilderness, that tactic was costly in manpower, and the idea of a flank attack appealed to him.

Of course, no one in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia had forgotten the incredible results such a ploy had brought when the late Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson circled around Hooker’s army in the same area they were now fighting during the Battle of Chancellorsville the year before. That stunning strike had assured Lee his greatest victory of the war. But it also had resulted in the costly death of Jackson from a friendly fire incident.

Instead of a costly frontal advance, the decisive blow would be delivered by a compact force slipping into place and then descending on the unsuspecting enemy. In the meantime, the main Rebel host positioned on the Orange Plank Road would keep up the pressure on the Federal front. Once the Rebel turning column began rolling up the Yankee line, the contingent along the Plank Road would plow into its disorganized opponent’s ranks, sending the enemy reeling backward or destroying it outright.

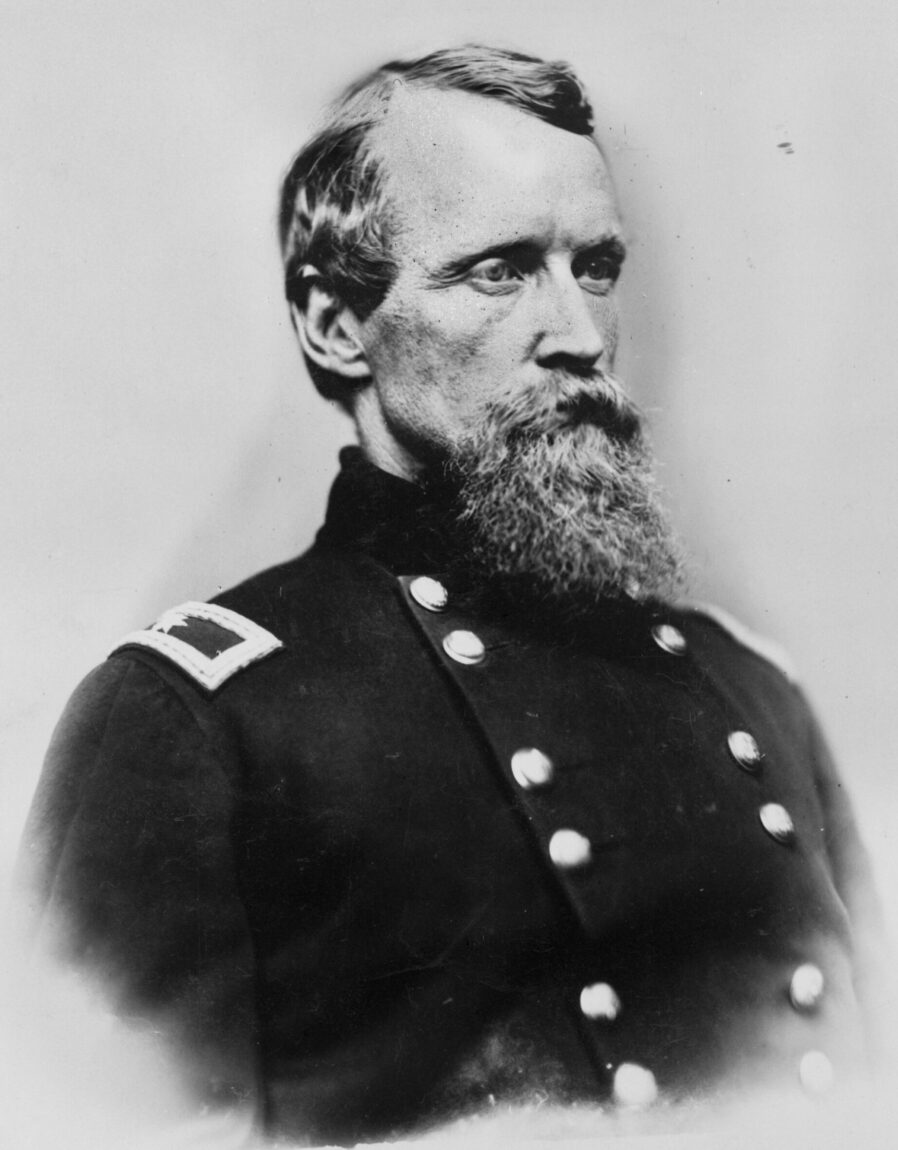

Armed with a strategy that promised the total destruction of a sizable portion of the Army of the Potomac and possibly victory in the current campaign, Longstreet energetically threw himself into making it work. Lee’s “Old War Horse” turned to his aide, Colonel G. Moxley Sorrel, the 26-year-old former bank clerk employed before the war by the Georgia Central Railroad, to coordinate the proposed sortie. The young Sorrel, a native of Savannah, had accompanied Smith on his exploration below the Plank Road and was intimately familiar with the route the Confederate flanking force would have to traverse to hit the enemy.

Calling his valued aide aside, Longstreet offered the young officer, who up to this time had no prior experience leading troops in combat, the chance of a lifetime. “Colonel, there is a fine chance of a great attack by our right,” said Longstreet. “If you will quickly get into those woods, some brigades will be found much scattered from the right. Collect them and take charge. Form a good line and then move, your right pushed forward and turning as much as possible to the left.” The corps commander then told Sorrel to strike hard, but only when he was sure that everything was in order.

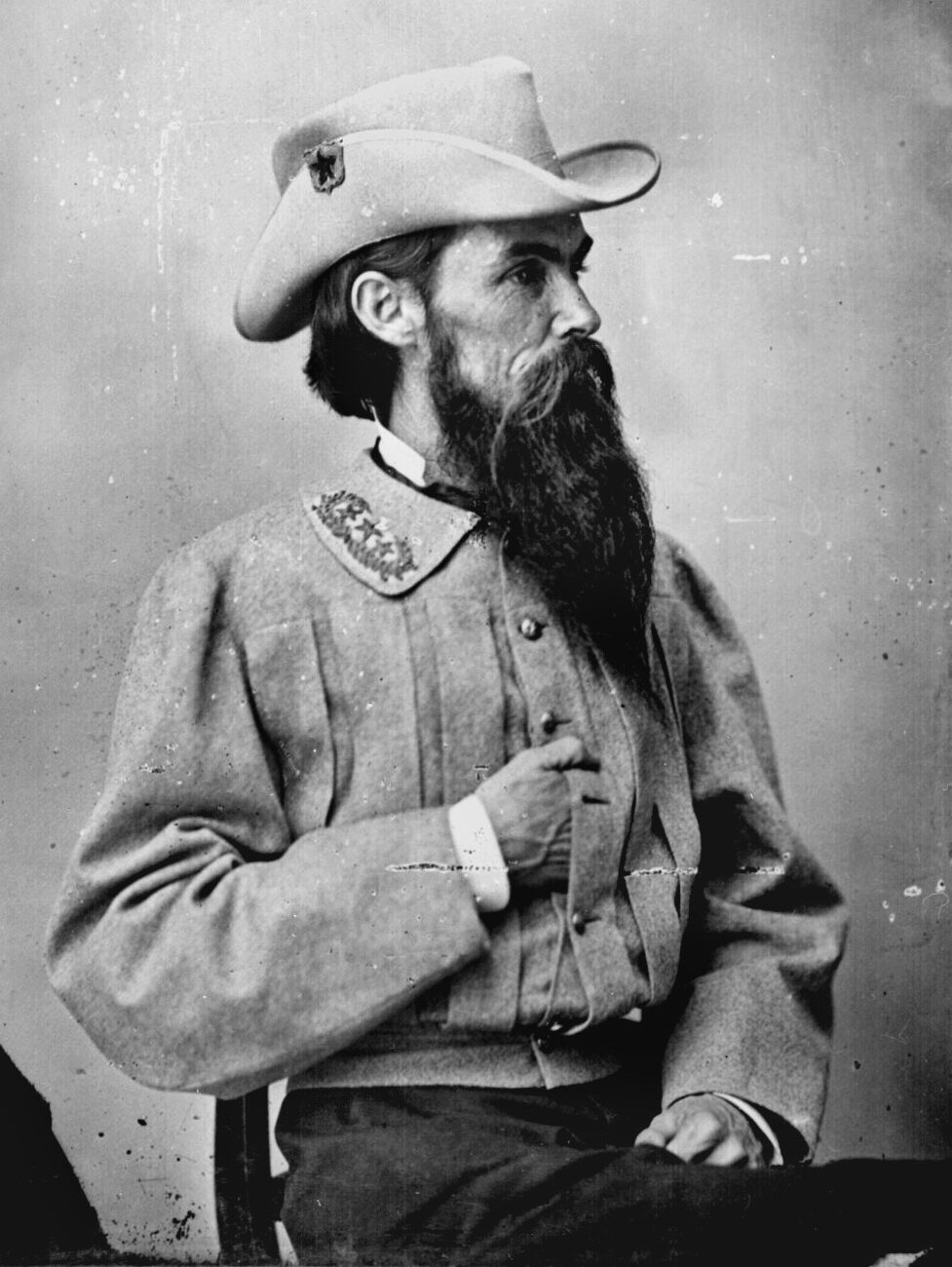

Sorrel immediately began to assemble the troops that would make the onslaught on the Federal flank. Participating in the assault would be four brigades from four different infantry divisions. Three of these formations were fresh. One of these fresh units was Brig. Gen. George Thomas “Tige” Anderson’s brigade from Field’s division, which had been held in reserve south of the Orange Plank Road during Longstreet’s counterattack earlier in the morning. Another was Wofford’s brigade, which was assigned to Kershaw’s division and had recently arrived on the battlefield with the supply trains of First Corps. Yet another one was Brig. Gen. William Mahone’s “Old Dominion” brigade of Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson’s Division of the Third Corps.

The one brigade that already had been engaged in the battle was under the command of Colonel John M. Stone, who was leading Brig. Gen. Joseph R. Davis’s brigade of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s division of the Third Corps. Stone had been cut off from the rest of Heth’s Division by Longstreet’s advance and so was neatly positioned to join the enterprise.

Controversy exists as to exactly who was in charge of the flank movement; that is, Mahone, the senior officer on the field, or Sorrel, Longstreet’s chosen deputy. In his battle report found in the Official Records, Mahone recorded,“As senior brigadier, I was by Lt. Gen. Longstreet charged with the immediate direction of this movement.” Fourteen years later he wrote that the movement “was made by my own [brigade] with two other brigades—Wofford’s and Tige Anderson’s—all under my immediate command.”

Sorrel, in his wartime memoirs, insisted that Longstreet had given him “full authority to control the movement.” His claim was supported by Colonel Walter Taylor, General Lee’s aide, in his writings after the war. Longstreet’s battle report supports Sorrel’s assertion as well. In it Longstreet states, “Special directions were given to Lt. Col. Sorrel to conduct the brigades of Generals Mahone, G.T. Anderson, and Wofford beyond the enemy’s left.” He added: “Much of the success of the movement on the enemy’s flank is due to the very skillful manner in which the move was conducted by Lt. Col. Sorrel.” Moreover, Longstreet wrote to Lee a few weeks after the Battle of the Wilderness recommending Sorrel’s promotion to brigadier general. Surely this request had to be based on Sorrel’s successful performance regarding the flank movement and the attack on the Federals that followed.

On reaching the unfinished railroad, the Confederate force swung east. The graybacks followed the railroad grade for a half mile to where it began to curve sharply south. The steady rattle of rifle fire could be heard to the left, indicating that the column had passed the battlefront and was positioned immediately below Hancock’s left boundary. Sorrel called his party to a halt. As he did, one by one the Rebel brigades faced north. On the right—closest to the sharp bend—was Anderson’s unit. Mahone’s brigade took position in the center, with Wofford’s brigade to its left. Stone’s men formed a second line in reserve. The Confederates were arranged to move to the attack up one of the ravines that Smith had discovered on his earlier scouting mission. The troops were packed tightly together, forming a mass of bayonets several lines deep. It is important to note that this picture of the Southern attack formation is up for debate due to an assertion made by Mahone that his brigade alone struck the enemy’s flank, while Wofford’s and Anderson’s troops traversed the woods between Hancock’s advanced line and the Brock Road.

The objective of the Confederate attack, the southern fringe of the Union II Corps, was held by the divisions of Maj. Gen. David B. Birney, Brig. Gen. Gresham Mott, and VI Corps Brig. Gen. George W. Getty’s division. Birney’s command was just below the Plank Road, followed on its left by Mott, with Getty stationed behind Birney. However, this seemingly impressive congregation of troops was misleading. The Union concentration near the Orange Plank Road had been weakened by casualties sustained first in Hancock’s attack and then Longstreet’s counterblow of the morning of May 6, as well as the loss of these combat units’ cohesion and alignment due to the battle and the terrain fought over that day.

Furthermore, on the evening of May 5, Hancock detailed most of Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s three-brigade division, Brig. Gen. Francis C. Barlow’s division, as well as most of the corps artillery to the high ground near the Trigg Farm and the Brock Road where they could easily cover the approach of any Confederate threat from that quarter. Hancock did this not knowing the whereabouts of Longstreet’s command and fearing that his wily opponent might cause untold mischief by striking II Corps’ left flank. Gibbon strengthened his area even more by placing two infantry brigades behind earthworks that formed a strong continuous barrier along the west side of the Brock Road, extending north from the Trigg Farm to the Orange Plank Road. But there were more complications.

Around 10 am on May 6, Hancock was forced to further dilute his strength on the Plank Road and immediately to its south when he was ordered to send reinforcements from his command to the north of the road to protect the Union V Corps flank, which had become dangerously exposed by the collapse of Wadsworth’s division as a result of Longstreet’s morning counterattack. Responding to the new orders, Birney pulled troops from his already weakened front and hurried them north. If the II Corps commander ever intended to redeploy his troops to buttress his southern front’s margin, he was prevented from doing so by the sound of battle farther down the Brock Road. What he heard was a clash between Yankee and Rebel cavalry, which in itself did not amount to much strategically, but in Hancock’s imagination presaged a likely attack by Longstreet on his flank from that direction. Consequently, he kept all his units in place securing the Brock Road to the detriment of his southern wing near the Plank Road. And the Confederates under Sorrel and Mahone were about to take full advantage of the situation.

At about 10 am quiet had settled over the Wilderness; even picket firing had pretty much ceased. The Federals of Hancock’s left on the Orange Plank Road were taking advantage of the temporary lull to make coffee and snatch a little sleep. Colonel Robert McAllister’s mixed 4th Brigade of Mott’s division, consisting of nine regiments from Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, held the extreme left end of the Union line. Curious as to what the Rebels were up to, the colonel and one orderly ventured beyond the Union picket line crawling from tree to tree seeking out the enemy’s location. Through the heavy growth the two spied Confederates in a ravine just ahead; a little farther on they spotted large numbers of grayback infantry gathered in the railroad cut. Working his way back to his own lines, McAllister dispatched an aide to his division leader detailing what he had discovered.

McAllister’s initiative notwithstanding, his warning came too late. As the Union officer’s missive to Mott sped on its way, Sorrel positioned himself in front of the 12th Virginia Volunteer Infantry Regiment of Mahone’s brigade and “with hat in one hand and grasping the reins of his horse with the other” the young staff officer said, “Follow me, Virginians! Let me lead you.” Striding forward in a compact body, the four Confederate brigades filed up the ravine straight for Hancock’s vulnerable flank. At the same time, Kershaw launched his division in another attack on the Union II Corps front, pounding Hancock along the Orange Plank Road. The result was what Longstreet had hoped. Sorrel’s blow landed squarely on the end of McAllister’s unsuspecting unit. Feverishly, the Union colonel attempted to swing his men around to face the on rushing graybacks now assailing his flank, but completing this maneuver in the dense woods proved a maddeningly slow process.

Alarmed by the sudden outbreak of musket fire from an unexpected quarter, Mott rode to McAllister to investigate. As the colonel began describing the situation to the general, more Confederates exploded from the woods to the west where McAllister’s front had been just minutes before. These were the lead elements of Kershaw’s force. McAllister’s men were caught in a crossfire between Kershaw to their front and Sorrel blasting them from behind. The bluecoats fired several defensive rounds and then broke for the rear. “At this time my line broke in confusion, and I could not rally them,” said McAllister in his battle report. The colonel barely managed to escape the debacle, his wounded horse collapsing on top of him as he reached the safety of the Union position on the Brock Road.

As McAllister’s command dissolved in flight, the victorious attacking Confederates moved north toward the Orange Plank Road. The 141st Pennsylvania Regiment, 1st Brigade, Birney’s division, was hit by the onrushing enemy and was quickly broken and forced to retire to the Brock Road. Colonel Samuel S. Carroll’s 3rd Brigade, Gibbon’s division, was the next Union formation to encounter the wrath of the Southern onslaught. Discovering they had been outflanked, Carroll’s men skedaddled, first by ones and twos, then by scores.

Farther north, Colonel Charles Weygant’s 124th New York Infantry Regiment (the Orange Blossom Regiment) of Brig. Gen. J.H. Ward’s 1st Brigade, Birney’s division, attempted to save his men from Sorrel’s advance. “Caught up as by a whirlwind,” he later wrote, his regiment was “broken to fragments, and the terrible tempest of disaster swept on down the Union line, beating back brigade after brigade, and tearing to pieces regiment after regiment, until 20,000 veterans were fleeing … toward the Union rear.”

Birney now arrived on the scene to try to stem the disaster. As he approached a group of Yankee fugitives on the Plank Road a Confederate artillery shell exploded almost underneath his mount, causing the horse to bolt down the thoroughfare as the general held on for dear life.

As Birney unceremoniously bounded from one side of the Plank Road to another after the exploding shell spooked his horse, Sorrel’s advance appeared unstoppable. Mahone seemed to appear everywhere, leading his Virginia Brigade, shouting orders over the din of battle, and driving his men relentlessly forward. Sorrel also exhibited fine leadership qualities by keeping his command moving even through difficult swamp-like terrain which momentarily slowed its advance. The Confederates chewed their way to the Orange Plank Road. It had taken no more than an hour. As Hancock ruefully conceded to Longstreet after the war, Sorrel’s exploit had “rolled me [Hancock’s command] up like a wet blanket.”

As Hancock’s line was crumbling, the Federal position north of it was being reorganized by General Wadsworth. But the oncoming Sorrel and his body of flankers threatened to crash into Wadsworth’s southern wing north of the road if Sorrel ventured that far. At the same time Sorrel’s movements appeared to menace Wadsworth from the south, Longstreet sent Field’s division against the Union general’s western front down the Orange Plank Road.

Responding to the dire situation, Wadsworth reoriented Brig. Gen. James C. Rice’s 2nd Brigade, Wadsworth’s division of the V Corps to a front parallel to the Plank Road facing Sorrel’s advancing Confederates. But a combination of Rebel artillery and an attack by Field’s infantry soon crumbled Rice’s position and sent his men running from the field. Then the Union situation got even worse.

After ordering one of his regiments to make a suicidal charge at the enemy coming from the west, Wadsworth got Brig. Gen. Alexander Webb’s 1st Brigade of Gibbon’s division to form a column on the Orange Plank Road to stop Sorrel. Soon the brigades of Brig. Gen. Henry L. Eustis above the road and Colonel Lewis A. Grant below it (both belonging to Getty’s division of the VI Corps) dissolved in flight after being hammered by the attacking Confederates advancing on the Plank Road. Joined by a brigade from the Union IX Corps, Webb held out for a short time but was eventually forced, as he put it, “to break like partridges through the woods for the Brock Road.” Shortly before Webb withdrew, Wadsworth was shot dead, a bullet tearing through the back of his head.

By noon Hancock’s line had been completely demolished, first by Sorrel’s flank move, then by Field’s frontal assault on the Orange Plank Road. All that remained was for Longstreet to sweep eastward, herding the enemy in front of him toward the Rapidan River and victory.

After Sorrel reached the Orange Plank Road he sought out Longstreet to get fresh troops to continue his advance. Meanwhile, his chief had conferred with Martin, who had made another reconnaissance and discovered that the uncompleted railroad cut could be used to make one more flank move, this time to envelope Hancock’s new defensive position on the Brock Road. But it was not to be. Shortly thereafter, Longstreet and a party of officers were fired on by friendly troops, critically injuring Longstreet.

Longstreet’s wounding stopped the proposed new attack on the Federals along the Brock Road. Lee, unaware of exactly how Longstreet planned to carry out the new turning movement and cognizant of the disorganized and exhausted condition of the troops designated to carry out the attack, set his priority to the reordering of Longstreet’s now scattered corps. This took time and great effort, and in the meantime Burnside’s Union IX Corps finally joined the battle when it attacked the Confederates above the Orange Plank Road in the afternoon. The result was some inconclusive sparring between the newly arrived Federals and Anderson’s division. The fighting along this part of the front soon concluded for the day but had caused a delay in Lee’s plans to continue his offensive against Hancock.

While Burnside was held in check north of the Orange Plank Road, Lee still intended to drive his enemy back across the Rapidan. But he was not going to launch a second flank attack as Longstreet hoped to do before he was injured. Lee instead sent his army in a ruthless full frontal assault up the Orange Plank Road into the teeth of Hancock’s now consolidated and strongly manned works along the Brock Road.

Lee’s attack on the Brock Road-Orange Plank Road intersection commenced about 4:15 pm. The Union position could not be carried. By 5:30 pm, the Confederate surge against the Brock Road defenses had been repulsed.

With the defeat of the Southern right along the Brock Road on the evening of May 6, combat on that sector of the Wilderness came to a close. Further fighting on the other end of the battle line occurred as night fell with moderate success achieved by the attacking Confederates, but this proved not to be decisive.

The brutal, two-day Battle of the Wilderness was essentially a frontal slugfest with the only innovative tactics being the two Confederate flanking maneuvers—one on the northern and one on the southern end of the battlefield. Of the two, the one carried out by Longstreet was the more effective. All the principal officers involved in the operation supported its implementation; the turning action was supported by a well-coordinated simultaneous frontal attack, and was executed flawlessly. It swept all before it and promised to secure a total victory for the South at the start of Grant’s Overland Campaign. Had the initial successes not become lost with the wounding of Longstreet, the effects on the outcome of the Civil War might well have been significant.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments