By Michael E. Haskew

In October 1942, at an obscure railroad whistlestop in the wastes of the Egyptian desert, the tide of World War II turned. True enough, Nazi spearheads had failed to take Moscow, capital of the Soviet Union, before the grueling winter of 1941 set in. However, the Germans had penetrated deep into the vastness of Russia and planned to renew their offensive with the spring thaw in 1942.

The first real strategic defeat of the German war machine on land during World War II occurred at El Alamein, 75 years ago this month. A desert war of attrition had built to a crescendo as the British Eighth Army defended the approach to the Egyptian capital of Cairo, only 60 miles to the east, against the vaunted Afrika Korps, under General Erwin Rommel. General Claude Auchinleck should receive credit for choosing El Alamein to make the desperate British and Commonwealth stand. His flanks were anchored on either side by the Mediterranean Sea and the impassable salt marshes of the extensive Qattara Depression.

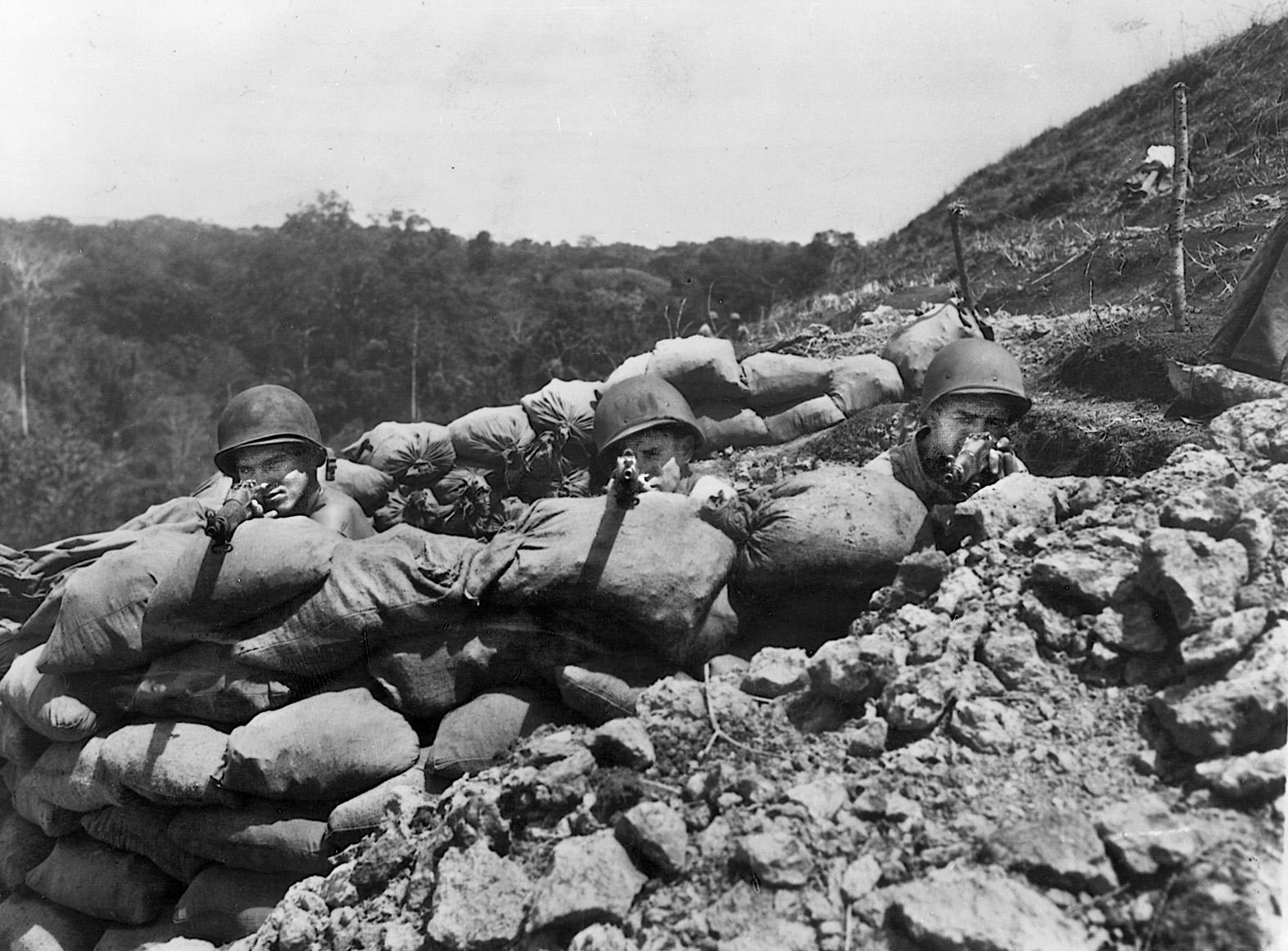

By October 1942, however, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff, had lost confidence in Auchinleck. He was replaced at the head of the Eighth Army by the dynamic, self-confident, and hard-driving General Bernard Law Montgomery. The British had stopped Rommel’s progess toward Cairo at the First Battle of El Alamein in July. Then, after receiving reinforcements that included 300 new American-built M4 Sherman medium tanks acquired through Lend-Lease, Montgomery launched the offensive at El Alamein on October 23. It was a tremendous risk.

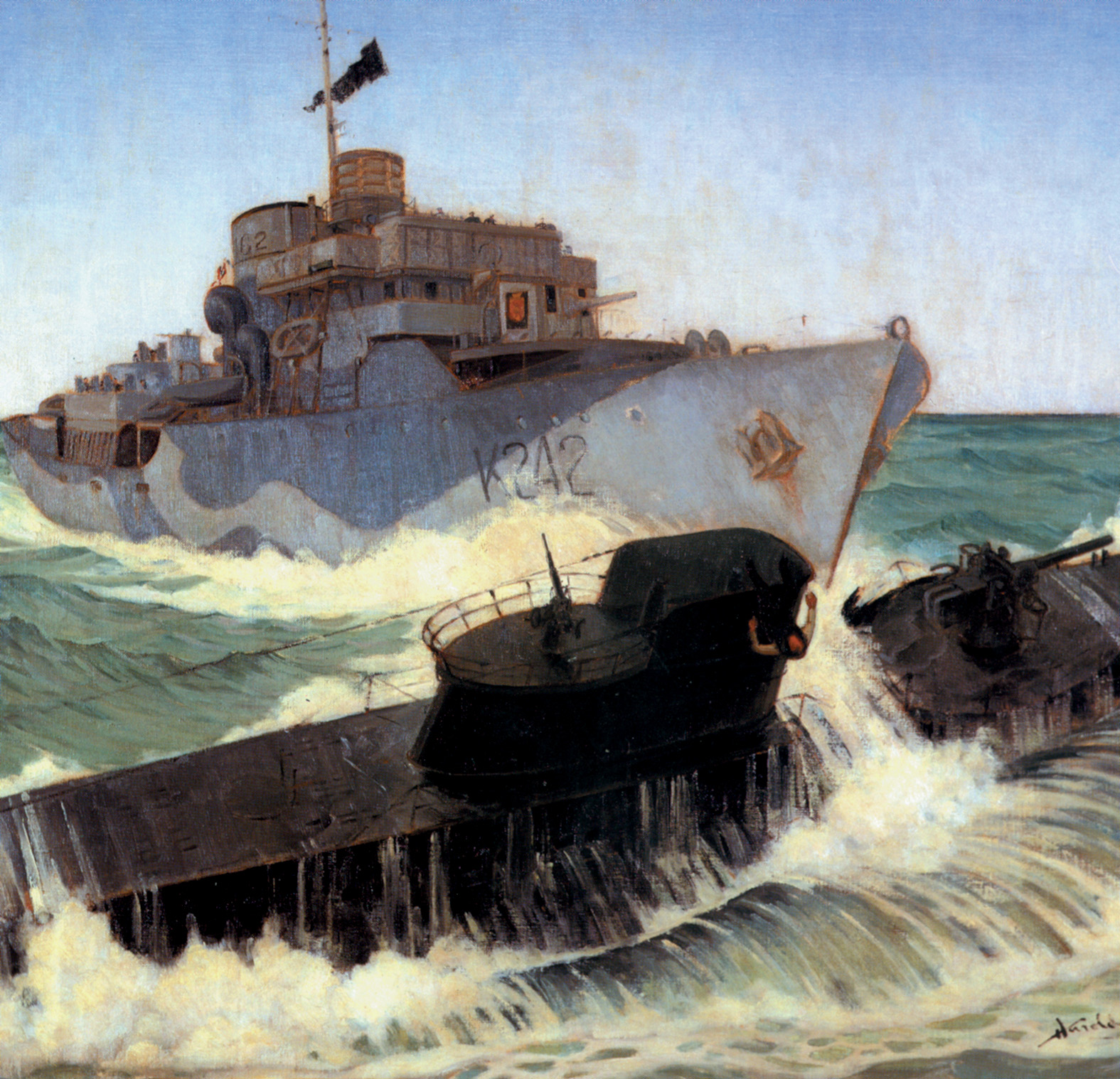

Fate may have actually played a role in the ensuing Allied victory. When the Eighth Army artillery barked to signal the start of the battle, Rommel was ill in Germany. Within hours, his second in command, General Georg Stumme, was dead of a heart attack. Command of the Afrika Korps fell to General Ritter von Thoma, and the coordination of the German response to the offensive suffered. German tank strength was whittled away during a dozen subsequent days of fighting. An initial strength of 500 tanks dwindled to only 30 serviceable vehicles as the Germans also had to contend with shortages of men and equipment due to supply lines that stretched across the Mediterranean through trackless miles of desert and were constantly harassed by Allied planes and submarines. Eventually, they were compelled to abandon key defensive positions.

By early November, the Afrika Korps was in full retreat across 1,000 miles of previously conquered territory. The British had captured 9,000 prisoners, including von Thoma. On November 4, British Army headquarters in Cairo issued a communiqué announcing that the Germans were on the run and reporting that they were being “relentlessly attacked by our land forces, and by the Allied air force, by day and night.” In response, King George VI sent a congratulatory message that read in part, “The Eighth Army … has dealt the Axis a blow of which the importance cannot be exaggerated.”

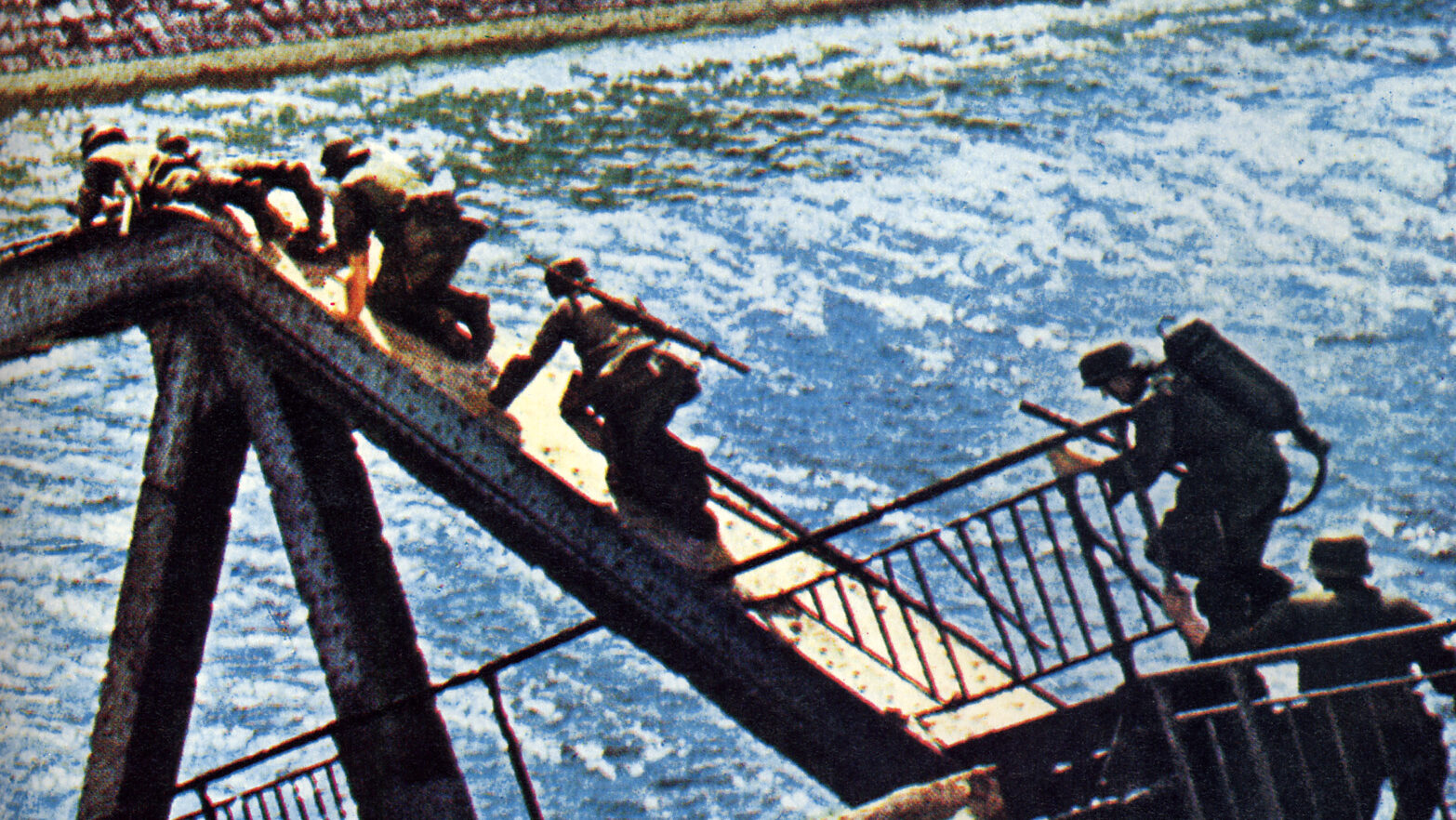

Four days later, Allied forces landed in the west at Oran, Algiers, and Casablanca. Operation Torch opened a second front in North Africa, and Axis forces were inexorably pressed in the vise. Total victory was achieved on May 13, 1943, when the remaining Axis troops in North Africa surrendered in Tunisia. Field Marshal Harold Alexander, commander of the 18th Army Group, reported to London, “We are masters of the Mediterranean shores.” Montgomery became a national hero and went on to command Allied ground forces in Western Europe.

Coupled with the great Soviet victory at Stalingrad in early 1943, the defeat in North Africa doomed the Axis—and the turning point had come at El Alamein.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments