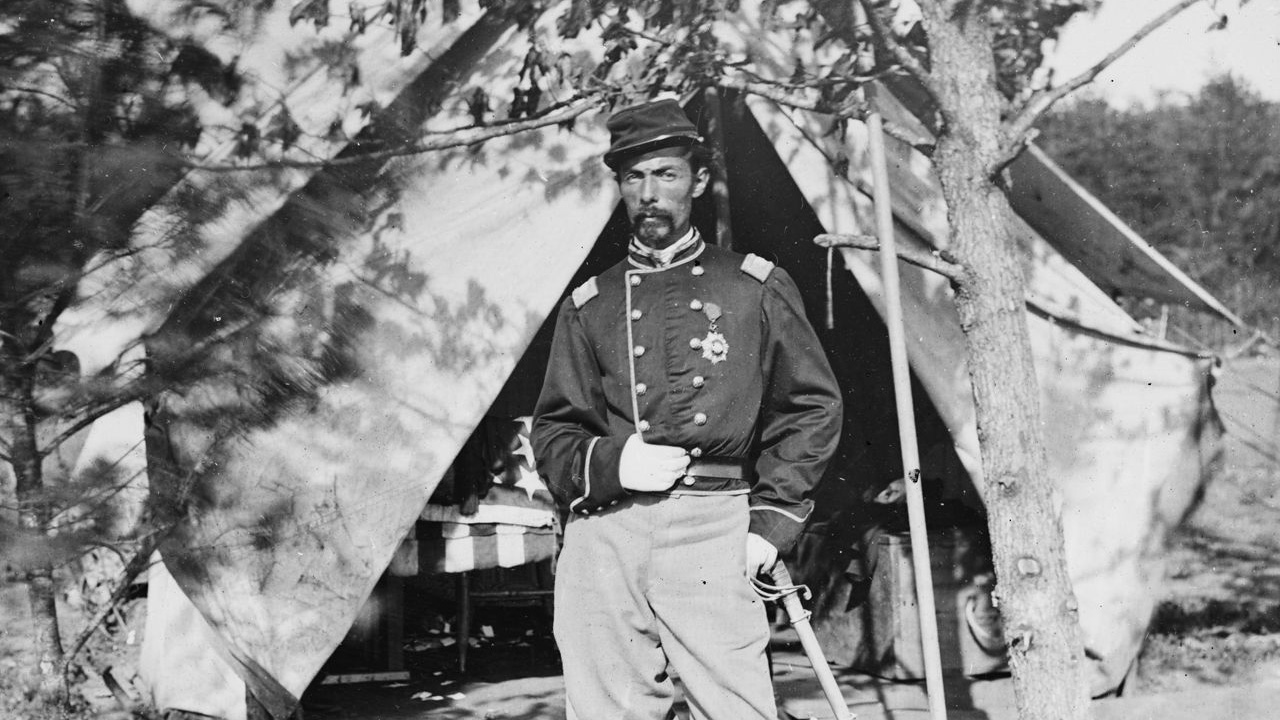

French immigrant Alfred Duffie may have fought for the Union during the Civil War, but the meddlesome presence of thousands of other French troops in Mexico almost led to a post-Civil War confrontation between the nation of his birth and the nation of his choice.

At the same time that Americans were fighting each other over the political and economic future of their country, Mexicans were embroiled in their own civil war, one pitting liberal anticlerics against conservative supporters of the Catholic Church and monarchy. After President Benito Juarez refused to pay Mexico’s outstanding foreign debt, French Emperor Napoleon III proclaimed the Latin American nation a monarchy and installed his kinsman, Austrian Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph, on the Mexican throne.

English and Spanish forces, which landed alongside the French within weeks of the outbreak of the American Civil War, soon left, but Napoleon III kept 40,000 of his best troops on Mexican soil to prop up Maximilian’s puppet regime.

The French presence in Mexico galled Americans, particularly those in the victorious North. Almost as soon as he had accepted Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Union commanding general Ulysses S. Grant turned his attention to Mexico. In May 1865 he personally dispatched his most aggressive lieutenant, Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan, to southern Texas to keep an eye on the “very saucy and insulting” French. Sheridan, who had removed Duffie from command while leading Union cavalry in the Shenandoah Valley, was ordered to monitor the Mexican-American border and provide secret aid to the deposed Juarez.

The ever-combative Sheridan was primed and ready to cross the Rio Grande and push the French out of Mexico single-handedly, despite the resistance of Secretary of State William Seward, who adamantly opposed American involvement in Mexican affairs. A golden opportunity soon presented itself when Imperialist General Tomas Mejia, commandante at Matamoros, refused to hand over several pieces of captured Confederate artillery, which Sheridan maintained belonged by rights to the U.S. government.

Threats and counterthreats flew back across the border, with the situation growing so ominous in the summer of 1865 that new President Andrew Johnson and his cabinet openly discussed the chance of war with France. But Maximilian, already overburdened by military challenges of his own, finally ordered Mejia to return the disputed artillery with the archduke’s personal apologies.

A second potential flash point arose a few months later when a party of American filibusters made an unauthorized foray across the Mexican border and were rounded up by Imperialist troops. Under Maximilian’s long-standing “black flag” decree, anyone caught fighting against his empire would be subject to immediate execution. Once again, American troops poised for a strike across the Rio Grande to rescue their countrymen, but in the end the raiders were spared and both sides again backed away from open conflict.

Finally, in April 1866, Napoleon III grudgingly announced that he would begin pulling French troops out of Mexico later that year. Predictably, the withdrawal of French forces propping up Maximilian led to the hasty fall of the usurper’s cardboard government. In June 1867, Juarez and his nationalist forces captured Maximilian and, despite a last-second appeal for mercy from the American government, executed the pretender before a Mexican firing squad.

Neither Johnson, Grant, nor Sheridan, who habitually referred to Maximilian as “the Imperial buccaneer,” evinced much regret over the emperor’s passing. As for Alfred Duffie, who had already mustered out of the U.S. Army and eventually became American consul in Cadiz, Spain, he maintained a discreet and no doubt politic silence over the whole affair.

Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments