By David A. Norris

As the Battle of Inkerman veered into chaos, British Maj. Gen. George Cathcart stepped into the role of a line officer, leading several hundred men to cut into the flank of an approaching Russian column. Their success lasted only moments. Back on the ridge that Cathcart had to abandon for the charge, a flood of great-coated Russian infantry poured over the crest. Cathcart immediately turned to deal with this new threat.

More Russian troops fired into his reactionary force of soldiers, seemingly from all directions. With just 50 men remaining, Cathcart led them in a dash for the ridge, but Russian bullets mowed down the remainder of his men. “I fear we are in a mess,” Cathcart said in the stoic manner of a cool-headed British commander to staff officer Major Charles L. B. Maitland. Shot through the heart, Cathcart had uttered his last words.

At the Battle of Inkerman on the outskirts of Sevastopol during the Crimean War, thousands of Russian, British, and French troops fought countless disconnected actions on ridgetops and in ravines, often while hidden by fog or drizzling rain. Momentum surged back and forth between the opposing sides, as regiments and broken detachments fought their way in and out of deadly situations. Senior commanders on both sides had little way of guiding the clash. On the field, line and company officers, as well as enlisted men, determined their own courses of action. Because of this, Inkerman is remembered as “The Soldiers’ Battle.”

European power politics took a strange turn in the early 1850s. Tensions in the Middle East drew Great Britain and France into an alliance with the Ottoman Empire against the Russian Empire. A riot between Orthodox and Roman Catholic churchmen over the control of Christian sites in Bethlehem erupted in 1853, which fanned the flames of conflict. Several Orthodox monks were killed in the riot, and Czar Nicholas I of Russia blamed the Turks, who controlled the region. The czar rejected diplomacy and instead demanded that the Ottoman Empire’s Christian lands be annexed by Russia.

The sovereign states of Western Europe viewed the once-feared Ottoman Empire by the 1850s as a harmless “Sick Man of Europe.” The Ottomans still maintained the balance of power in their domains, and made no trouble for Great Britain and France; instead, it was a growing and more aggressive Russia that worried the Western powers. Russia, with its vast interior that was practically landlocked save for a few ports on the edges of its empire, sought to strengthen its military and commercial power by seizing warm water ports. Nicholas I saw the Bethlehem riots as a pretext for seizing control of the Bosporus, the narrow strait between Asia and Europe that linked Russian territories on the Black Sea with the Mediterranean Sea.

Prussia and Austria eyed the simmering conflict, but ultimately did very little given that their interests were not threatened. The same could not be said for London, which expressed considerable alarm at the thought of Russia interfering with British access to India via the Middle East. Meanwhile, newly enthroned French Emperor Napoleon III, a nephew of Napoleon I, wanted to increase trade with the Ottomans and enhance French military and diplomatic prestige on the world stage.

Nicholas I sent Russian two armies to invade the Ottoman vassal states of Moldavia and Wallachia. The Russians crossed the Pruth River on July 3, 1853, and 12 days later marched into Bucharest. Ottoman Sultan Abdulmejid I responded to the violation of Ottoman sovereignty by declaring war on Russia on Oct. 23, 1853.

Next, Czar Nicholas directed Russian Admiral Paul Nakhimov to attack the Ottoman fleet in the Black Sea anchored at Sinope on the north shore of Anatolia. Using newly developed naval shells, the Russian fleet inflicted devastating damage on the wooden hulls of the Turkish ships in the one-sided naval action that unfolded on Nov. 30, 1853. Only one Turkish steamer escaped the carnage.

In the aftermath of Russia’s combined land and naval campaign against Ottoman forces, the threat of Russian dominance in the region led Great Britain and France to come to the aid of the Ottoman Empire, which appeared to be outmatched by the aggressive Russians.

London and Paris paid scant attention to Russia’s northern port of St. Petersburg. Instead, they directed their military effort towards negating Russia’s quest for warm-water access through the Black Sea. The Western Allies responded by assembling large expeditionary forces for deployment to the Black Sea.

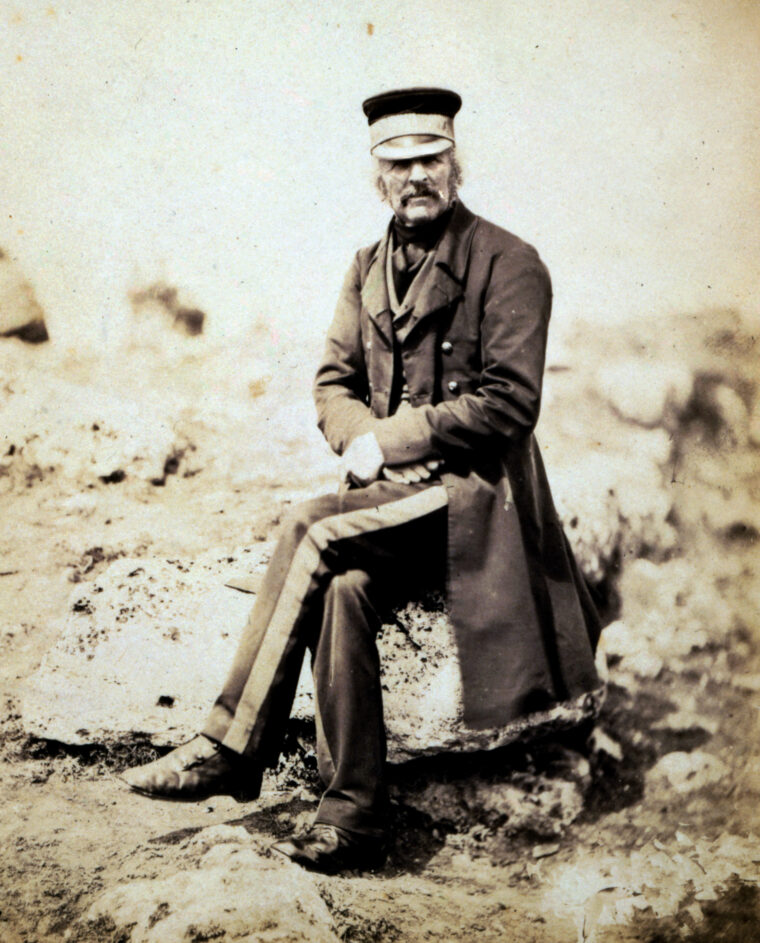

General Fitzroy James Henry Somerset, commonly known as Lord Raglan, commanded 24,000 British troops. A veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, Lord Raglan, who was wed to a niece of the Duke of Wellington, had lost an arm at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.

Marshal Jacques Leroy de St. Arnaud commanded an initial French army numbering 40,000 troops. France’s first contingent dispatched to the region comprised four infantry divisions and two cavalry brigades. As the leader of the largest Allied contingent, St. Arnaud was the overall commander of the allied forces arrayed against the Russians.

The French and British initially landed near Constantinople in April 1854 to protect it from a possible Russian attack, but shortly thereafter advanced their base to Varna on the west coast of the Black Sea, where their expeditionary forces could be resupplied by their respective fleets.

The Russians pressed deeper into the eastern Balkans while the British and French were establishing a foothold in the region. The Russians besieged the Ottoman fortress of Silistria in Bulgaria on May 11, 1854. But when Czar Nicholas learned on June 14 that Austria had assembled 50,000 troops in Transylvania and that Emperor Franz Joseph I was considering joining the Allies, he ordered his troops to withdraw on June 23. Russian troops did not comprehend the reason for the retreat, and their morale plummeted as a result.

The Turks pursued the Russians as they withdrew, inflicting heavy losses on their demoralized columns. By that time the British and French had embarked their forces at Varna, where they busied themselves setting up their respective camps on the plains around the city.

London soon decided that the objective for the Allied expeditionary forces should be the Russian naval base at Sevastopol. The government issued orders for Raglan to capture it. The two allied armies relocated once again. They set sail on Sept. 5 for Calamita Bay north of Sevastopol, where they landed on Sept. 18. Their troops needed to march just 30 miles to take the Russian stronghold and naval base of Sevastopol.

Prince Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov, who commanded Russia’s land and sea forces, was on hand in the Crimea. The first major battle between the opposing sides occurred on Sept. 20, when the allies succeeded in dislodging Menshikov’s 37,500 troops from their defensive position behind the Alma River.

Menshikov withdrew his defeated Russian army toward Sevastopol. Quick moves by the Allies could well have overrun Menshikov and taken Sevastopol before the Russians could arrange their defenses, but the Allies did not follow up on their victory. Menshikov had no desire to have his army trapped inside Sevastopol, so he took advantage of the slow pursuit of the Allies to retreat across the Tchernaya River, two miles east of Sevastopol, where he planned to await reinforcements. He left the defense of the city to just 5,000 soldiers and 10,000 sailors from the Black Sea Fleet.

Fortunately for the Russians, a gifted army engineer named Colonel Eduard Totleben had arrived in Sevastopol that the summer and had immediately put the soldiers and sailors, as well as the residents of the city, to work improving its antiquated defenses. While thousands toiled to improve the walls and construct strongpoints, the Russian admirals of the Black Sea Fleet sank seven of their ships in the mouth of the bay on Sept. 23. The sailors from those ships and others were directed to man artillery positions along the city’s landward walls. When the Allies reached the Russian stronghold on Sept. 27, its fortifications already forbade an immediate assault.

More troops joined Menshikov, eventually increasing the size of the Russian forces to 120,000. The Russian army far outnumbered the Allies’ initial 74,000 French, British, and Turkish troops. The approach of winter was a worrisome prospect. Disorganized and far from supply sources, the British were especially low on food and suitable winter clothing. Moreover, the Allies lacked sufficient troops to both maintain a siege and protect themselves from attack against their siege lines by the Russian army outside of Sevastopol.

The British and French armies established new supply bases at the tip of the Crimean Peninsula in October that were in close proximity to their siege lines. The new British base was at Balaclava and the French base at Kamiesh.

Russian reinforcements arriving from the Danubian front under General Pavel Liprandi enabled the Russians to go on the offensive before the onset of winter. An obvious target was the Allied right, east of Sevastopol, which was held by a small portion of the British contingent. Liprandi crossed the Tchernaya on Oct. 25 and attacked the British forces in what became known as the Battle of Balaklava. The battle was a draw, and the Russian army withdrew. Russian infantry poured out of Sevastopol the following day to make a sortie against the British infantry stationed on Inkerman Ridge. The small action, which was not much more than a skirmish, became known as Little Inkerman.

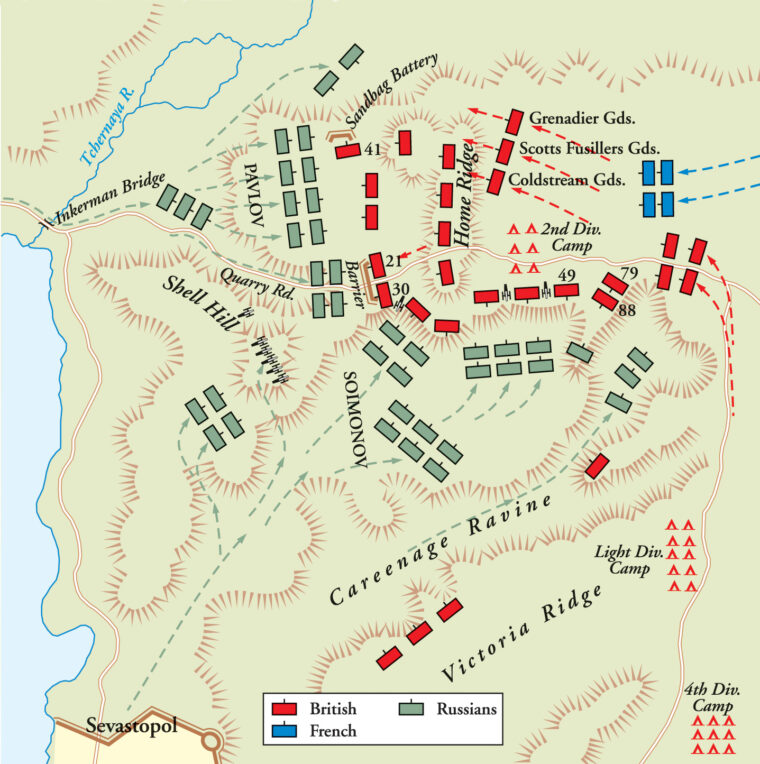

Although the Russian attacks failed to break the siege, they showed that the Allies were overextended and that an assault at a vulnerable point could break their lines. A new attack was planned in early November, again aiming at the British forces holding the Allied right. Two forces were to move simultaneously. Lt. Gen. P. I. Paulov would cross the Tchernaya and hit the British from the north, and Lt. Gen. Feodor I. Soimonov would lead an attack on the British left from Sevastopol.

Soimonov was to advance along the western side of the Careenage Ravine, a depression that rose to heights the British called Victoria Ridge. From there, he would strike the left flank of the British Second Division. The move was intended to drive a wedge into the Allied line, cutting off the isolated Second Division. The Careenage Ravine led to a creek flowing into Sevastopol Harbor, but for most of its length it was a dry canyon that meandered through a bleak landscape of barren and steep rocky slopes. Paulov would cross the Tchernaya via the Inkerman Bridge to join Soimonov. Once the two armies had joined up, Gen. Peter Andreivich Dannenberg would assume command of the operation. Meanwhile, troops remaining in the Sevastopol defenses would keep the French busy with diversionary attacks.

The target of the combined Russian attack was Lt. Gen. George de Lacy Evans’ British Army’s Second Division on the spur of Home Ridge at the southern end of Inkerman Ridge. Inkerman Ridge, which was situated east of the Careenage Ravine, took its name from the village of Inkerman, which was located on the heights across the Tchernaya.

The Second Division’s position on Home Ridge two miles east of the Sevastopol defenses was held by its 2,700 men backed by 12 guns. To block the Post Road, which ran north and south through Home Ridge, the British built a work they called “The Barrier.” Another high stretch called “Fore Ridge” rose just northeast of Home Ridge. Near the side looking down toward the Tchernaya River, the division built another work called the “Sandbag Battery,” although no guns were placed in it yet. Behind Home Ridge was the camp of the Second Division.

Half a mile south of Home Ridge, along the Post Road, 1,350 men of the elite Guards Brigade camped on the Sapoune Heights. This ridge overlooked the valley where the legendary Charge of the Light Brigade had occurred during the fighting at Balaklava, just 11 days earlier. Half a mile west of the Guards, across the Careenage Ravine atop Victoria Ridge, were 1,400 soldiers of Maj. Gen. William Codrington’s brigade of the Light Division.

Brig. Gen. George Buller’s brigade of the Light Division, as well as the Fourth Division under Maj. Gen. George Cathcart and Maj. Gen. Richard England’s Third Division, were further away but still within three miles of Home Ridge. But as it would turn out, just 3,000 British troops were enough to have an effect on the impending battle. The nearest available French troops, under General of Division Pierre Francois Joseph Bosquet, were two miles in the rear of the Second Division.

Evans, who was a veteran of the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, had been injured in a bad fall from his horse on Oct. 30. As a result, his second-in-command, Maj. Gen. Sir John Pennefather, would lead the division in the upcoming battle.

Soimonov launched his advance in the gloomy predawn hours. The Russians tramped through a steady cold rain that fell on the already wet terrain. Six thousand Russian troops, led by 300 riflemen, edged toward the enemy forward outpost on Shell Hill. Nine thousand more Russians waited in reserve. Some distance behind Soimonov’s foot regiments, wheels of Russian gun carriages creaked and rumbled.

At 4:00 a.m., the British sentries heard the deep tolling of the church bells in Sevastopol. The sentries thought little of the distant bells; after all, it was Sunday morning. Just as Russian commanders had intended, the tolling of the bells conspired with the misty darkness to cover the sounds of the Russian movements in the valley below.

Paulov was scheduled to attack simultaneously with Soimonov; however, the former’s men were delayed for several hours as his engineers rebuilt a bridge across the Tchernaya. Without waiting for Paulov, Soimonov pressed his attack.

Lacking suitable guides or maps, Soimonov mistook his route and proceeded along the wrong side of the ravine. Poised along the eastern edge of the chasm, the Russian riflemen leading the advance ended up hitting the British right. In effect, he was attacking along the ground chosen for Paulov’s wing. A spatter of gunfire began at 5:00 a.m. as the Russian riflemen neared the pickets along the outer perimeter of the British defenses.

A surprise dash by the Russians in the vanguard drove the outnumbered British pickets off of Shell Hill, and burly Russians rolled the czar’s guns into place. Thirty-eight pieces of artillery—twenty-two 12-pounders and sixteen 6-pounders—were in battery only half a mile from Home Ridge, with their gunners ready to go into action. Further away in the rear, two Russian warships waited, ready to hurl their shells at long range into the British lines.

In the Second Division camp, the soldiers were already engaged in a battle against the drizzling rain that thwarted their efforts to light their breakfast campfires. When the first shots were heard “an alarm spread through the camps,” wrote Captain Edward Bruce Hamley, a British staff officer with the Royal Horse Artillery. “Breathless servants opened the tents to call their masters; scared grooms held the stirrup; and staff officers, galloping by, called out that the Russians were attacking in force.” Panicking in the pandemonium, pack animals escaped their handlers and clattered through the camp.

Pennefather hurled his entire division against the onrushing enemy. Forming into two ranks, they poured a well-directed fire into the Russians. Already the surprise attack was running into trouble. Paulov’s men were nowhere to be seen. Soimonov’s regiments had little room to deploy in the broken terrain, and in the room available for their front could only deploy a few battalions at a time, not enough to take full advantage of their numbers.

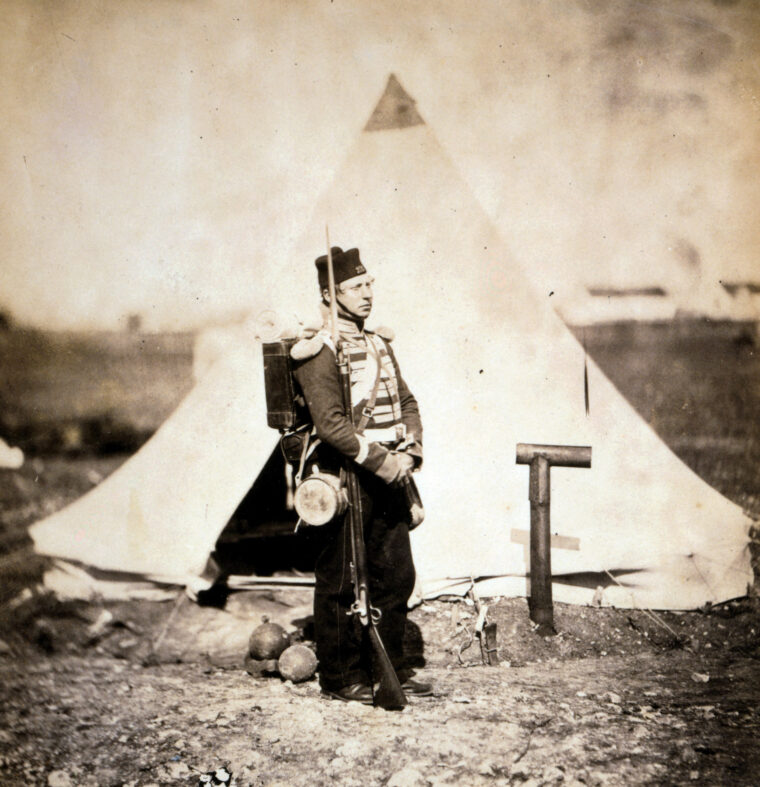

So far as firearms, the British had a decided edge. Nearly all of them were armed with rifle-muskets, which fired the new and deadly Minié ball. Other than the rifle-bearing sharpshooters, all the Russians carried smoothbore muskets. Although they were percussion cap muskets rather than flintlocks, they were still accurate to just 100 yards.

By 7:00 a.m., the Russian gunners on Shell Hill could see the Home Ridge through a gap in the fog. The Russian guns fired into the British camp with “round shot and large shell, and tent after tent was blown down, torn to pieces, or sent into the air,” wrote a correspondent with the New York Times. Lt. Col. John Miller Adye observed the effects of the Russian artillery fire as he rode through the camp. “Round shot were bounding along, tents were being knocked over, horses killed at their pickets, whilst blankets and great coats were lying about amid the brushwood, thrown down, apparently, by our men had hastily fallen in and hurried to the front,” he wrote.

Damage could have been far worse to the British, had not Pennefather nearly emptied the camp by sending his entire command into the battle. As it was, the Second Division fended off the attacks and awaited reinforcements. When another Russian column approached Pennefather’s left, the 49th Infantry fired into them. Fixing bayonets, the 49th charged and pushed the attackers back to Shell Hill.

Soimonov drew upon his 9,000 reserves for a renewed assault, and led it himself. British reinforcements, including Buller with the 77th and 88th Infantry from the Light Division, were arriving just in time. A six-gun battery of nine-pounders under Major Samuel Philip Townsend waited, their cannon muzzles facing into the murky haze.

“The crest of the hill was covered with smoke, and the entire ground there thickly covered with brushwood, through which we with the greatest difficulty moved the guns,” wrote one of Townsend’s officers. “Suddenly the smoke cleared away, and we discovered the Russian infantry in great force within 10 yards of us. I shall never forget the aspect of those fellows, dressed in their long grey coats and flat glazed caps, firing most deliberately at our poor gunners, and picking them down like so many crows.”

Scattered foot soldiers, their units shattered by the advancing Russians, poured through the British artillery. A handful of men stayed with the guns, but not enough to hold them. Townsend gave the order to withdraw the battery, but it was too late. Lieutenant Frederick Miller just had time to spike one of his guns. Moments later, Townsend was killed by an exploding shell that struck him on the head and literally crushed it into pieces.

Miller drew his sword, and gallopped his horse towards the gun. He cut down first one Russian and then another. His quick action complled a dozen Russian soldiers to turn back. Meanwhile, Miller’s gunners fought furiously using anything at hand, including their swords, rammers, sponge staffs, and fists to fend off the muskets and bayonets of the attackers. Even so, they lost three of their precious cannons.

General Buller led his regiments in a charge, joined by Pennefather’s 47th Infantry. At about 7:00 a.m. “the ground was thickly covered with brushwood, and there was a pretty thick fog, which prevented our seeing a powerful force of about 3,000 men, who almost completely surrounded our poor devoted regiment,” wrote a sergeant of the 77th Regiment of Foot that was published in the press. Most of the regiment was deployed elsewhere in the trenches around Sevastopol, he noted. “Our four companies did not amount to over 300 men,” he wrote. “General Buller exclaimed, ‘My God! We are surrounded!’ and he ordered a volley to be fired into them, and charged them with the bayonet.”

“[An] artillery officer came to us and said, “47th will you let them take our guns from us,”’ and we all gave a shout to charge them,” wrote a drummer of the 47th in another letter picked up by the press. “My sword was broken in my hand, and I worked away with the bayonet of one of our poor fellows that was killed by my side.”

The countercharges pushed back the enemy and recovered the three captured guns. Two of the guns were found hastily spiked with wood splinters, and they were restored for firing soon enough. Buller was knocked out of action when his horse was killed by artillery fire, but Lieutenant Miller rode back to his battery without a scratch.

This first phase of the Russian attack stalled. Another column, of Russian sailors and marines, rose from the Careenage Ravine. They were caught between two groups of British infantry, and were driven back down the ravine. General Soimonov was shot dead and his second in command was wounded at the same time. With their senior leadership lost, Soimonov’s division reeled back. Part of the force joined Paulov’s 15,000 men, just now arriving after their long delay getting across the Inkerman Bridge.

Paulov’s force formed a line facing the Sandbag Battery on their left and the Post Road north of the Barrier on their right. The Barrier was a simple work of “a wall of loose stones, crossing the road and stretching into the coppice on each side,” wrote Hamley. “The Barrier was about a quarter of a mile from the Sandbag Battery, which was to the east higher up on Fore Ridge.

Dannenberg arrived and took overall command of the czar’s forces. He directed the battle from Shell Hill, amid his artillery. Although they outnumbered the British guns, his batteries were taking incoming fire. The commander’s horse was struck down by a fragment of an exploding shell. Another horse was found for Dannenberg, but as he was about to pull himself into the saddle, that horse was also shot. Mounting his third horse, he continued to press attacks on the British lines.

“The gloomy character of the morning was unchanged,” wrote British war correspondent William Howard Russell of the battlefield conditions that day. “Showers of rain fell through the fogs, and turned the ground into a clammy soil, like a freshly-ploughed field.” The grey cloth of the greatcoats worn by the Russians helped them blend in with the mist. On higher ground, the air sometimes cleared and allowed visibility for considerable distances, only to close up again with more fog.

Another surge of Russian infantry drove the British back from the Barrier. Alerted to the loss of the fortification, Pennefather sent the 21st Royal North British Fusiliers, the 63rd Infantry, and the Rifle Brigade. This combined force took back the Barrier, and the British held on to it for the rest of the day.

Neither the Barrier nor the nearby Sandbag Battery were more than the most minor sort of defensive works. Yet, in a battleground with few distinctive landmarks, they were focal points for the bitterest fighting of the day. Brig. Gen. Henry William Adams held the Sandbag Battery with 700 men of the 41st and 49th Regiments of his brigade. The arrival of the Guards Brigade, comprising the Coldstream, Grenadier, and Scots Fusilier Guards regiments, from their camp brought Adams another 1,300 men to the beleaguered battery.

Waves of Russians contested the cold and muddy ground, and control edged back and forth. Furious charges and countercharges, and the turmoil of troop movements, created a gap in the British line between the Barrier and the Sandbag Battery. Prince George, the Duke of Cambridge, who was a lieutenant general and a grandson of King George III, joined the defenders of the Sandbag Battery. Raglan ordered Cathcart to support them on their left in order to fill the gap.

Cathcart, though, saw the advance of enemy units menacing the right of the Sandbag Battery. He ordered Brig. Gen. Arthur Wellesley Torrens to attack the Russians with 400 men. Torrens’ horse was shot from under him, struck by five bullets.

Seeing his second-in-command had gotten up and was still directing the attack, Cathcart shouted, “Nobly done, Torrens!” Just then, a Russian bullet pierced Torrens’ lung, splintered one of his ribs, and was caught in his greatcoat. With Torrens out of action, Cathcart himself took direct command, but when he glanced to the rear he saw Russian troops pouring into the once-again open space in the British line.

Caught between enemy troops approaching from both sides, Cathcart’s men fired as their cartridge boxes grew lighter and lighter. When Cathcart called on his men to fire again, they protested that they had no more ammunition. With a remark destined to become something of a memorial to him, Cathcart replied, “Then, have you not your bayonets?”

With 50 men from the 20th Regiment, Cathcart attacked the Russians holding his former position. Enemy bullets steadily cut down the dwindling band of British soldiers. Cathcart’s last words, spoken to Major Maitland, were “I fear we are in a mess.” Seconds later, Cathcart fell from his horse, shot dead by a Russian musket ball.

Before the disintegration of Cathcart’s attack, his success lured other British troops to push forward down the ridge. Bold as it was, this move left some of the ridge unattended, and Russian troops poured into the gap and threatened to turn the British right. A French regiment that just reached the front held on and repulsed the enemy attack and saved the Allied right.

With the fog and smoke obscuring the broken terrain of the battlefield, regiments and battalion fought their own battles with little or no direction from above. “Colonels of regiments led on small parties, and fought like subalterns, captains like privates,” Hamley wrote of the confused and desperate struggle. “Once engaged, every man was his own general….The tide of battle ebbed and flowed, not in wide waves, but in broken tumultuous billows.”

Russians of the Okhotsk Regiment mounted a determined effort to overrun the Sandbag Battery. Some tried to push their way inside through the embrasures. Others paused momentarily beneath the wall, where they were sheltered from the fire of the Guards. Those Russians who fired away their last bullets and hurled their empty bayonet-tipped muskets like javelins over the wall. After throwing their improvised spears, some took up rocks and lobbed them at the Coldstream Guards, who were holding the battery. In turn, the Coldstreams threw the sharp-tipped muskets back at the Russians. Where the parapet was too high to fire over, the guardsmen stood on the bodies of their dead comrades to raise their aim high enough.

Eventually the Russians surged around the flanks of the Sandbag Battery. They blocked the open rear of the battery, and the Coldstream Guards found themselves trapped with their backs to the sandbag wall. But the Guards rushed ahead and broke through the Russians surrounding them, and escaped to find temporary safety with the main British line.

The Guards had only a short respite. Two more Russian regiments marched down the Post Road. To counter them, and prevent the Russians from rising from the ravines to occupy the high ground so tenaciously held by the British, the Guards were sent back to regain the Sandbag Battery. With bayonets and clubbed muskets, they drove through the enemy and regained the battery. When General Bosquet saw the human wreckage strewn around the Sandbag Battery later in the battle, he gasped, “What a slaughterhouse!”

With his staff on Home Ridge, Raglan sent orders to bring up two 18-pounder guns. Then, they had to wait under heavy enemy fire for the pieces to arrive.

With Raglan was Brig. Gen. Thomas Fox Strangways. Long ago the brigadier had distinguished himself as a young artillery officer when attached to the Swedish forces at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813. Russian Czar Alexander I, who was also present at Leipzig, had removed from his coat his own Order of St. Anne medal and presented it to Strangways. Now Strangways was under the fire of the army of Nicholas I’s son, Alexander I.

At 9:30 a.m. a shell exploded inside the horse of one of Raglan’s staff officers. Shell fragments struck down another officer’s horse, and nearly severed Strangways’ leg. “The poor old general never moved a muscle of his face,” an eyewitness told Russell. “He said merely, in a gentle voice, “‘Will anyone be kind enough to lift me off my horse?’”

Strangways was borne to the rear. Nothing could be done for him and he lived only two more hours. By some accounts, Strangways was wearing his Russian medal when he died. The general’s horse, which bolted after the shell burst, was found unharmed; oddly enough, even the stirrup leather was undamaged.

Captain Robert Nigel Fitzhardinge Kingscote, an aide to Raglan, wrote about his narrow escape from death on Home Ridge in a letter, “A shell pitched on the flap of my saddle behind my leg and sword, which it bent, fell on the ground, where I saw it fizzing,” he recalled. “But before I could kick my horse out of the way it burst, without touching either me or my horse. Why the horse’s ribs were not broken I cannot conceive.”

Back on Victoria Ridge, Codrington refused to take any reinforcements, and sent any available troops across the ravine to the more endangered sections of the Allied line. To Codrington’s left was the Lancaster Battery, a work intended to accommodate heavy naval guns for bombarding the Sevastopol works. Sailors remained in the battery, although all the artillery save one heavy Lancaster 68-pounder gun had been removed. With some difficulty, the Lancaster gun was turned to bear on the Russians on the other side of the ravine. Rocket fire from the battery also aided in their defense.

When Russian troops approached the battery, the massive 68-pounder was of little practical use against infantry at close range. Five sailors withstood the enemy fire, firing from the parapet with a stream of muskets loaded by the wounded and handed up to them. Two of the sailors were killed, but survivors James Gorman, Thomas Scholefield, and Thomas Reeves each received the Victoria Cross for his valor at Inkerman.

Codrington’s men were exposed to deadly fire from Russian sharpshooters, who took cover in caves along the ravine. One hundred and twenty Royal Marines were with Codrington, who dispatched some of them to clear away the enemy snipers.

Corporal John Prettyjohns and several marines captured one of the caves. The corporal shot four Russians in the initial clash. Although they held the cave, the marines were nearly out of ammunition, and they could see Russian infantry streaming up the slope toward them in single file.

Prettyjohns ordered the men to gather as many stones as they could, and they waited until the Russians reached their position. Prettyjohns seized the first enemy soldier to reach the marines’ position, and threw him down the slope. As the soldier tumbled down, he knocked down others who were climbing the slope behind him. From the top of the ridge, the marines broke up the attack with a barrage of heavy rocks and stones. Corporal Prettyjohns became the first Royal Marine to be awarded the Victoria Cross.

By mid-morning, enough French troops joined newly arrived British units to enable the Allies to hold their line. Among the French were the exotic and colorful Zouaves with their North African-inspired uniforms of red and blue, topped with red fezzes for headgear. The eye-catching attire and daring exploits of the Zouaves in the Crimean War subsequently inspired many American units of the late antebellum period and the American Civil War to adopt their exotic uniforms.

In the final phase of the battle, the flagbearer of the French 6th Regiment of the Line was shot dead. Lt. Col. Francois-Auguste Goze seized the fallen standard, but lost it when a bullet smashed into his arm. Colonel Edmond-Jean-Armand Filhol de Camas, commanding the regiment, rallied his men with the cry, “To the flag, my children!” They charged and took back their banner. Filhol de Camas was mortally wounded, but his men held on to the flag.

Fighting on the battlefield peaked after midday. When the weather temporarily cleared about noon, it seemed to war correspondent Russell that the Russians were beginning to break off the engagement and pull back. But more misty rain began to fall and under the cover of the returning fog, the Russians rallied but their final attacks were repulsed with great losses.

The pair of British long 18-pounders ordered by Raglan reached the front. Their greater range enabled the big guns to hammer the Russian gun crews on Shell Hill, whose shorter range pieces could not hit back. Two new French horse artillery batteries unlimbered and joined the bombardment. Return fire dwindled away as Dannenberg’s exhausted army began withdrawing from the field at 1:00 p.m. They split into two groups. The late General Soimonov’s surviving troops trudged back into Sevastopol, and Paulov’s men streamed back over the Inkerman Bridge.

The battle was “a gloomy though a glorious triumph” wrote Hamley. His comrades were famished, and too bone-weary to exult in victory as they had after the bloody clash at Alma. “All our army was fasting all day,” wrote a drummer of the 47th Infantry. “It was [midnight] before I could get a morsel to eat; and if you were to see my hands, all covered with blood and tearing the raw pork in my teeth, you’d say that I was hungry.”

Of the 8,500 British troops on hand at Inkerman, 2,640 were killed, wounded, or missing. French losses among their 7,500 troops came to 1,465 men. Russian losses were much higher, estimated at 12,000 of the 42,000 troops engaged.

At Inkerman the Allies halted a potentially game-changing attack and held their positions. A determined and aggressive follow-up might have shattered the Russian Army and ended the war, but the Allies lacked sufficient reserves to overpower the Russians. The Russians then adopted a defensive posture, drawing the Allies into a grueling siege that lasted until September 1855. When it was all over, sickness and disease had felled far more British soldiers at Sevastopol than Russian guns.

Long after the war, John Adye, who by then had obtained the rank of major general, heard a tale from an old veteran. Adye had obtained a place for the soldier, who won the Victoria Cross at Inkerman, in the Yeomen of the Guard. While on duty at Buckingham Palace, the yeoman spoke with a Russian grand duke who was interested in his decorations. Seeing the Inkerman clasp on the medal, the grand duke told the yeoman that he too had been at Inkerman. “The old Yeoman,” wrote Adye, “in telling me the story, said he thought he might be so bold, so he replied, ‘Well, sir, if you [were] at Inkerman, I hope we may never meet again on so unpleasant an occasion.’”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments