By Todd Avery Raffensperger

On the night of November 20, 1983, Armageddon went prime time. Over 100 million Americans tuned in to the ABC television network to watch the two-hour drama The Day After. This depiction of a hypothetical nuclear attack on the United States attracted a great deal of publicity and controversy. Schools made watching the film a homework assignment, discussion groups were organized in communities across the country, and even the secretary of state at the time, George Schulz, took part in a question-and-answer session hosted by ABC after the film’s broadcast. That a mere made-for-TV movie could garner such attention from a leading figure in the Reagan administration indicates how real the fear of a nuclear apocalypse was at the time. But almost no one watching that Sunday night realized just how close fiction came to reality in the fall of 1983.

The possibility of the world’s two greatest military powers destroying each other and the earth in a full-scale thermonuclear war was a fear shared by many throughout the world. At the time, both the United States and the USSR maintained huge nuclear arsenals of over 20,000 nuclear warheads each. In North America and Western Europe, nuclear freeze movements were gaining new members daily, with mass demonstrations that routinely numbered in the tens of thousands.

World events seemed to only reaffirm people’s fears. It was the third year of the presidency of Ronald Reagan, a man who had built his political career on a virulent hatred for all things communist. His 1980 victory over incumbent President Jimmy Carter had largely been the result of his hard-line stance against the Russians. A former film actor with a natural flair for the dramatic, Reagan both inspired and shocked people with his hardcore rhetoric, such as his statement before the British House of Commons in 1982 that the Marxist ideology would be relegated to the “ash heap of history.” Perhaps his most memorable and antagonistic remarks came on March 8, 1983, when Reagan referred to the Soviet Union as the “focus of evil in the modern world” and an “evil empire.”

The actions of the Reagan administration in its first three years backed up his uncompromising rhetoric. To match the USSR’s huge expenditures on its armed forces, Reagan and Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger initiated one of the largest peacetime military buildups in American history. Weapons programs such as the M1 Abrams tank, Trident nuclear submarine, and Stealth bomber were accelerated, while previously cancelled programs such as the B1 Lancer strategic bomber and the MX Missile were resurrected. To achieve the goal of creating a 600-ship navy, the Defense Department brought all four of its mammoth World War II-era Iowa-class battleships out of mothballs and returned them to active duty.

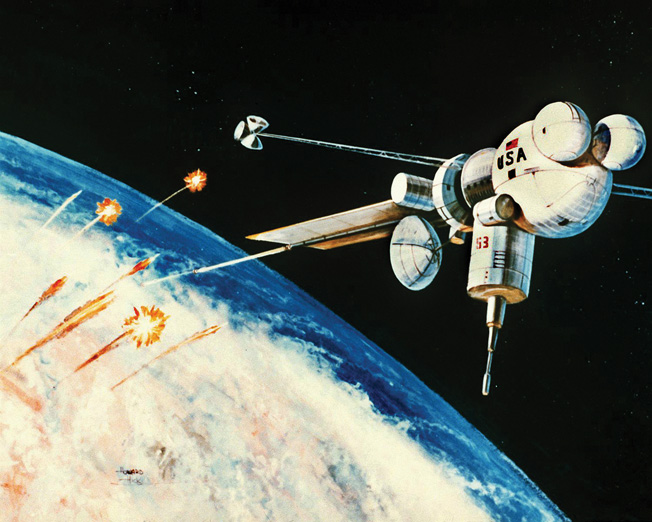

“Star Wars” and Fleetex 83: On the Brink of Nuclear War

On March 23, 1983, Reagan took the superpower rivalry to a new level when he unveiled the Strategic Defense Initiative Program during a live television address. The SDI program, more popularly referred to as “Star Wars,” was to provide an orbital shield that would protect the United States—at least partly—from a nuclear strike. Reagan and supporters of the project argued that such a defense network, while not being able to completely block a full-scale strike from Russia, would at least cut down its effectiveness considerably and would be able to destroy smaller scale strikes, accidental nuclear launches, or missile attacks from rogue states. Reagan proposed to share the technology with the Soviets in a bid to eliminate the threat of nuclear war altogether.

To Yuri Andropov, then general secretary of the USSR, Reagan’s intentions spelled trouble. Andropov had dedicated his entire life to defending the Soviet Union, whether as a member of the partisans fighting behind German lines during World War II or as head of the Soviet secret police, the KGB. His supreme ambition to lead the nation had been realized with the death of Leonid Brezhnev in November 1982.

Andropov was scared to death of Ronald Reagan. He sincerely believed that Reagan meant what he said about the Soviet Union being an evil empire and seeing himself as a crusader who would not have any qualms in ordering the USSR’s destruction. During the summer and fall of 1983, events only served to add fuel to Andropov’s burning fears. In Western Europe, the United States prepared to deploy the latest generation of Intermediate Range Ballistic Missiles (IRBM), the Pershing II. The Pershing missiles were a countermove to the Soviet deployment of the larger SS-20 IRBMs. But while the SS-20s could only reach targets in Western Europe, the Pershing IIs had the range to hit targets inside the USSR itself. It represented a new threat that the Soviets found intolerable.

In April and May of that year, as the rhetoric between Washington and Moscow escalated, the United States Navy conducted a series of fleet exercises in the Northwest Pacific known as FLEETEX 83. With more than 40 warships massed into three carrier battle groups, it was the largest concentration of American naval might in the Western Pacific since World War II. The massive exercise involved the counterclockwise sweep of these waters with the extreme right flank of the formation coming close to Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. Round-the-clock air operations from the carriers Enterprise, Coral Sea, and Midway were meant to make the Soviets respond by putting their eastern air bases on constant alert. During the course of the maneuvers, a combined flight of six F-14 Tomcat fighters from Midway and Enterprise flew over Zelyony Island in the Kuril Archipelago, a violation of Soviet airspace that the U.S. Navy later insisted was an accident, an explanation that the Soviets obviously did not accept.

FLEETEX 83 was only the largest effort to taunt and tease the Russian bear. Throughout the summer, Navy and Air Force reconnaissance aircraft repeatedly violated Soviet airspace, forcing the Soviet Air Force to constantly scramble its fighter planes to intercept violators. By the time the Soviet planes were in the air, the American planes would already have left the USSR and been on their way back to base. Furious leaders in Moscow put increasing pressure on their pilots to be more aggressive with the American intruders. This increasingly tense game of cat-and-mouse laid the groundwork for one of the most tragic episodes of the Cold War.

“The Target is Destroyed”

On the night of September 1, Soviet fighters scrambled yet again, this time because an American RC-135 reconnaissance plane had flown into Soviet airspace in the area of the Sakhalin Islands. The RC-135 was a modified Boeing 707, an aircraft regularly used as a commercial air liner but also used by the Air Force for communications, refueling, and intelligence gathering. The planes were based in the Aleutian Islands, and their principal mission was to monitor Soviet missile tests on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

On this particular night, not all of the radar installations on Sakhalin were functioning properly, and they would repeatedly break down during the night. Nevertheless, Soviet radar operators detected what they thought was the RC-135 before a pair of Sukhoi Su-15 fighters made visual contact with the plane. The lead pilot, Lt. Col. Gennady Osipovich got close enough to see that the plane was a large, four-engine configuration. After trying to signal the aircraft, Osipovich received instructions from the air defense command to shoot down the plane. After firing warning tracers at the aircraft to try and get its attention, Osipovich followed his orders and launched two R98 air-to-air missiles at the huge plane. Upon seeing the missiles connect with the target and explode, Osipovich radioed back in his trained, professional tone, “The target is destroyed.”

However, the plane that Osipovich brought down was not an RC-135. The reconnaissance plane had already completed its mission and left Soviet airspace on its way back to the

Aleutians. The malfunctioning radar installations had instead picked up another flight, a commercial airliner that was off course from its scheduled flight to Seoul. It was Korean

Air Lines Flight 007, a 747 jumbo jet with a four-engine configuration similar to that of the RC-135. Two missiles hit the rear fuselage of the plane and sent it spiraling into the Sea of Japan, taking all 269 passengers and crew to a watery grave. Ironically, one of those passengers was a fiercely anticommunist conservative congressman from Georgia, Lawrence McDonald.

As news broke of the catastrophe, the world reacted with shock and outrage. Reagan, a man usually known for his gentle manner and good humor, was enraged. In a nationally televised address that same night, he condemned the shootdown as an “act of barbarism, born of a society which wantonly disregards individual rights and the value of human life and seeks constantly to expand and dominate other nations.” Radio exchanges between the Russian pilots and their base had been monitored and recorded by the Japanese Ministry of Defense, which in turn passed the recordings on to Washington. That evening Reagan played a portion of the recordings, and Osipovich’s infamous four words, “The target is destroyed,” would be played and replayed on news programs throughout the world.

Moscow’s reaction to the outrage further hurt Soviet credibility. At first, Moscow refused even to admit that a shootdown had taken place. Then they conceded only that an “incident” had occurred. When the Kremlin finally admitted that one of its planes had shot down an aircraft, it was insisted that the plane was on a reconnaissance mission and that blowing it out of the sky was completely justified. Osipovich himself was never reprimanded for shooting down the civilian airliner; in fact, he was awarded a salary bonus of 200 rubles.

Able Archer and Grenada

On September 29, nearly a month after the KAL 007 tragedy, Andropov issued an official declaration to the Soviet people, stating that as long as Ronald Reagan occupied the Oval Office there could be no chance of negotiating with the United States. According to the general secretary, the United States was embarking on “a militarist course that represents a serious threat to peace.” Angry rhetoric between the United States and the USSR was nothing new, but never before had the leader of either superpower declared that he would not negotiate with the other.

On October 25, international tensions were ratcheted up further when the United States launched an invasion of the small Caribbean island of Grenada. The official purpose was to rescue 250 American students at St. George’s School of Medicine who were caught in the middle of a power struggle between two communist factions. It took little more than 48 hours for the American invasion force to overwhelm the 1,200-man Peoples’ Revolutionary Army and a 780-man Cuban contingent. The fighting, while brief, was fierce, with the Americans suffering 134 casualties to 500 Grenadan and Cuban losses. The invasion was the largest American military operation since Vietnam and the first time that a communist nation had been invaded since North Korea.

The invasion seemed to confirm in Andropov’s mind what he had most feared. He saw in Grenada an example of the American president’s willingness to use force. A week after the landings in Grenada, NATO commenced a 10-day exercise codenamed Able Archer 83. It involved most of Western Europe and was directed from Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) at Casteau, Belgium. Able Archer was a complex simulation of a hypothetical war with the Warsaw Pact that included a series of fictional military exercises escalating to the launch of nuclear weapons.

As Able Archer commenced, NATO vehicles rumbled throughout the West German countryside sending simulated radio reports about Soviet and East German forces crossing the border and invading the Federal Republic. SHAPE received these reports and relayed them to the various situation rooms, where NATO leaders analyzed and considered their reactions.

While Able Archer went through imaginary alert stages for the next several days, the center issued to its agents a checklist of specific events that would indicate that a nuclear attack was imminent. NATO leaders surmised that it would take 7 to 10 days for the United States to fully prepare for a nuclear war from the time such a decision was made. Five days into the Able Archer exercise, Moscow appeared to believe that actual preparations were being made for such a war.

The Soviets Prepare to Strike

On November 9, the seventh day of Able Archer, Western intelligence reported that pilots of the Soviet 4th Air Army had been placed on alert at their air bases in East Germany and Poland. The warplanes included Sukhoi Su-24 “Fencer” precision-strike bombers capable of delivering tactical nuclear weapons. Their two-man crews sat ready in their cockpits, waiting for the order to stand down or the order to take off and proceed to their designated targets in Western Europe. NATO intelligence also reported the movement of the Soviet Red Banner Fleet from its bases in the Baltic and the North Sea. Information was coming in that the Soviets were preparing their most powerful weapons, their 300 ICBMs (Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles) for immediate launch on Andropov’s order. The general secretary sent messages to his counterparts in the Warsaw Pact warning them of the high probability of war breaking out and ordered Soviet ballistic submarines at sea to go into firing positions off the coast of the United States.

As these reports filtered in to Western intelligence agencies, there initially was little alarm. Analysts and experts who examined the information simply could not believe that the Soviets seriously thought that NATO was preparing a nuclear first strike. At this point, the West did not have any real clue just how dangerous the situation had become. It would take the warnings of a double agent to finally get the West suitably alarmed.

Oleg Gordievsky came from a family of spies. His brother had joined the KGB in 1957, and his father had served in the KGB’s Stalinist predecessor, the NKVD. Gordievsky himself had joined in 1962. By 1983, he was a KGB colonel, serving in London as the resident delegate to the KGB mission, the highest ranking KGB officer in the United Kingdom. His decision to work for the other side came from his thorough disillusionment with Soviet communism. In 1974, while serving in the KGB mission in Copenhagen, Denmark, he started to actively cooperate with Great Britain’s MI6.

Gordievsky understood the depth of suspicion, paranoia, and downright panic that was seizing the Kremlin. As he received directives from Moscow about the imminence of a nuclear attack, he did not hesitate to inform his British handlers. “When I told the British,” he later recalled, “they simply could not believe that the Soviet leadership was so stupid and narrow-minded as to believe in something so impossible.” It was not until Gordievsky passed along the directives he had received that the British really started to pay attention. Copies of these directives made it into the hands of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who forwarded the documents to the Central Intelligence Agency.

At CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, the documents landed on the desk of the agency’s mercurial director, William Casey, who personally delivered the documents to the White House, where they were first glimpsed by Reagan’s National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane. At first, McFarlane was skeptical, but the urgent reports by Gordievsky, Britain’s highest-placed spy in the KGB, were enough to finally convince him. McFarlane took the problem to the president.

Defusing the Crisis

A flurry of diplomatic cables flashed from Washington to Moscow, giving repeated and wholehearted assurances that Able Archer was simply an exercise. Reagan sent presidential adviser Brent Scowcroft to the Soviet capital to give further assurances, face to face, on behalf of the president that the United States would never launch a surprise attack on the USSR. The effort was not enough to convince Andropov of Reagan’s good intentions, but it was enough for him to watch and wait. Throughout the rest of the Able Archer exercise, Soviet forces stayed on alert, braced and ready to move at a moment’s notice. Only when the exercise finally concluded on November 11 did the Soviet Union give the order for its strategic forces to stand down.

In the end, simple human reasoning overcame the ideology and overheated rhetoric of the age. The deep mistrust and animosity between the two sides were not enough to trump the staggering price that would have been paid for acting upon them. Nuclear winter was averted—for the time being at least—but the chill had come uncomfortably close.

In August of 1984, President Reagan, while doing a sound check for a radio broadcast said, “My fellow Americans, I’m pleased to tell you today that I’ve signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever. We begin bombing in five minutes.”

While it didn’t go out live, it was recorded, and got out into the news a couple of days later. Needless to say, the Soviets were not pleased, and got a lot of traction out of it for their propaganda outlets.

We should note that Putin’s current paranoia toward the West is based on his belief that external military pressures caused the internal collapse of the Soviet Union which he continues to regret. He ignores the social and economic problems that made a far greater contribution to Russia’s situation. For that reason, the final chapter of Russia and the West has yet to be written.