By David W. Rickman

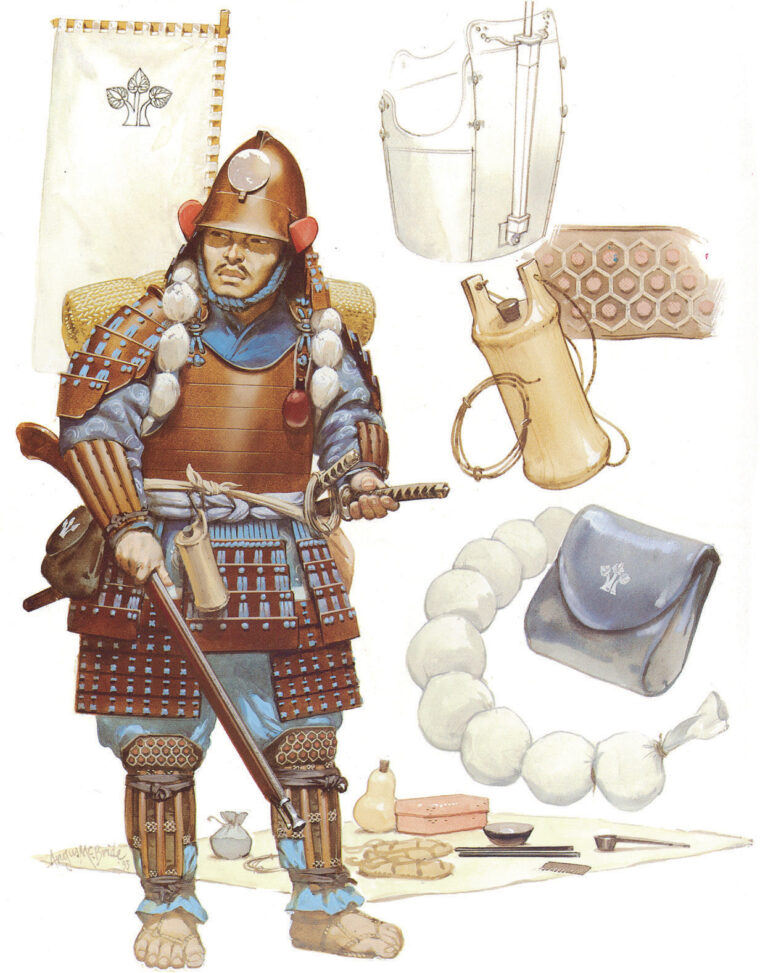

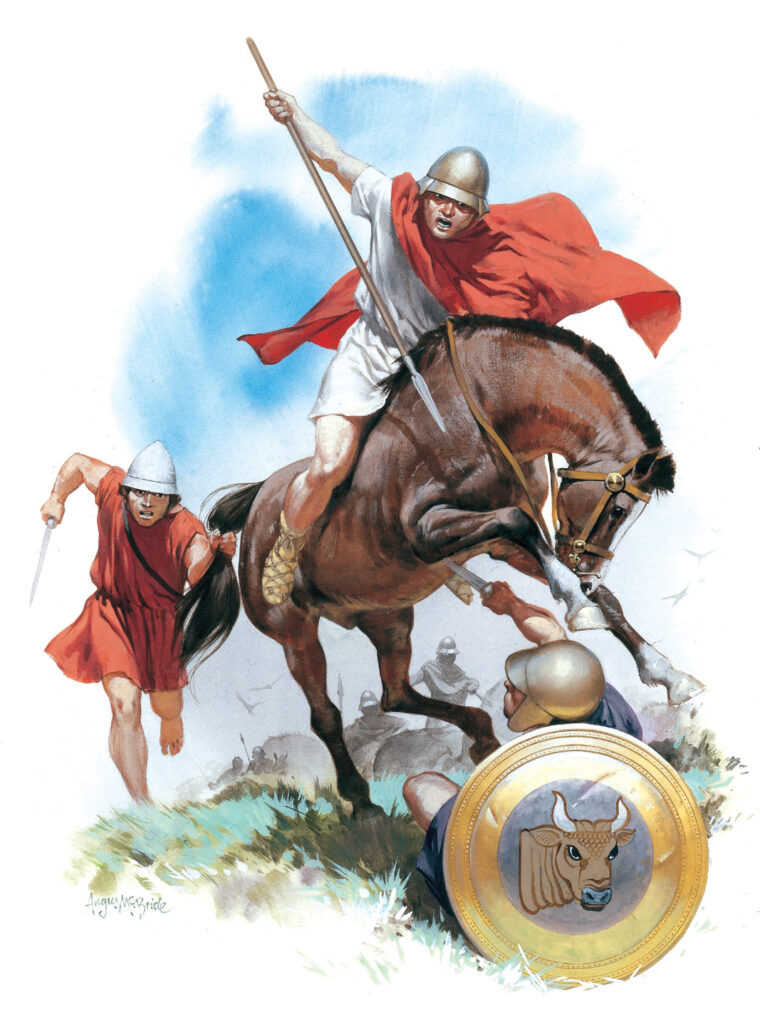

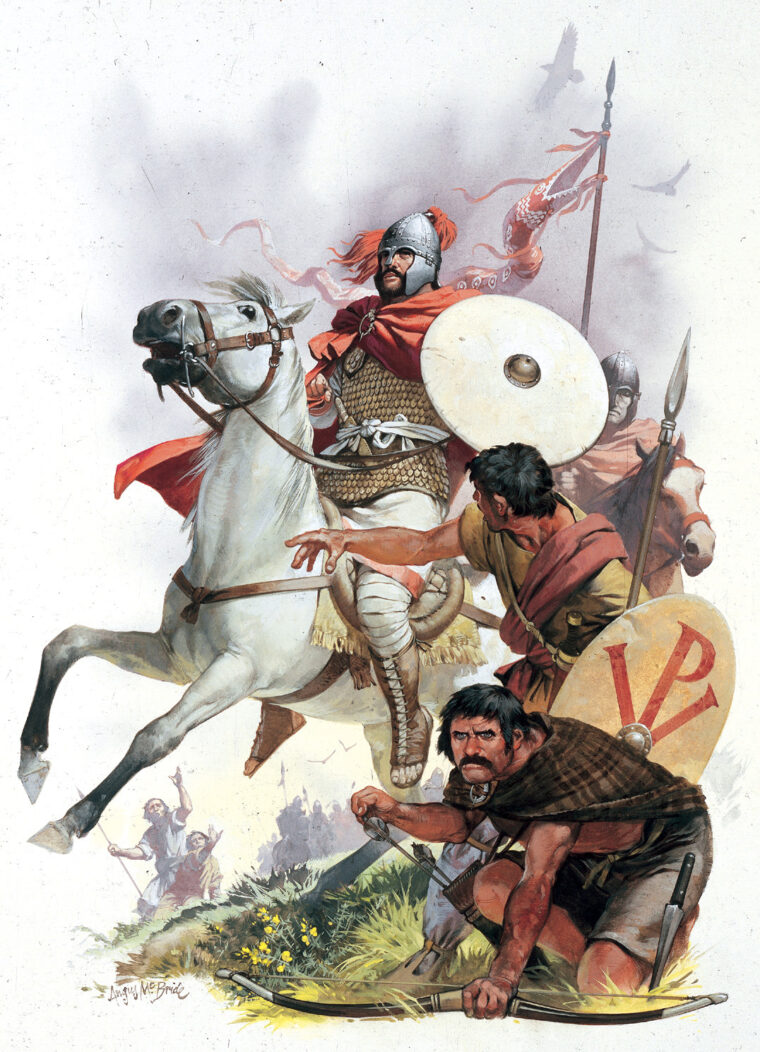

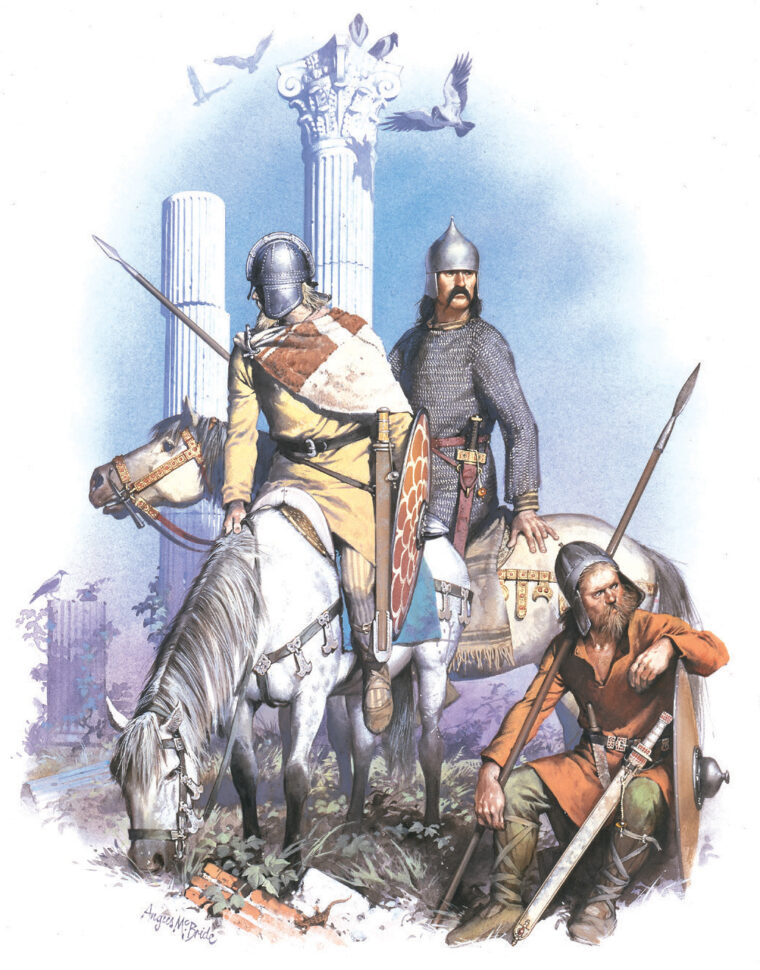

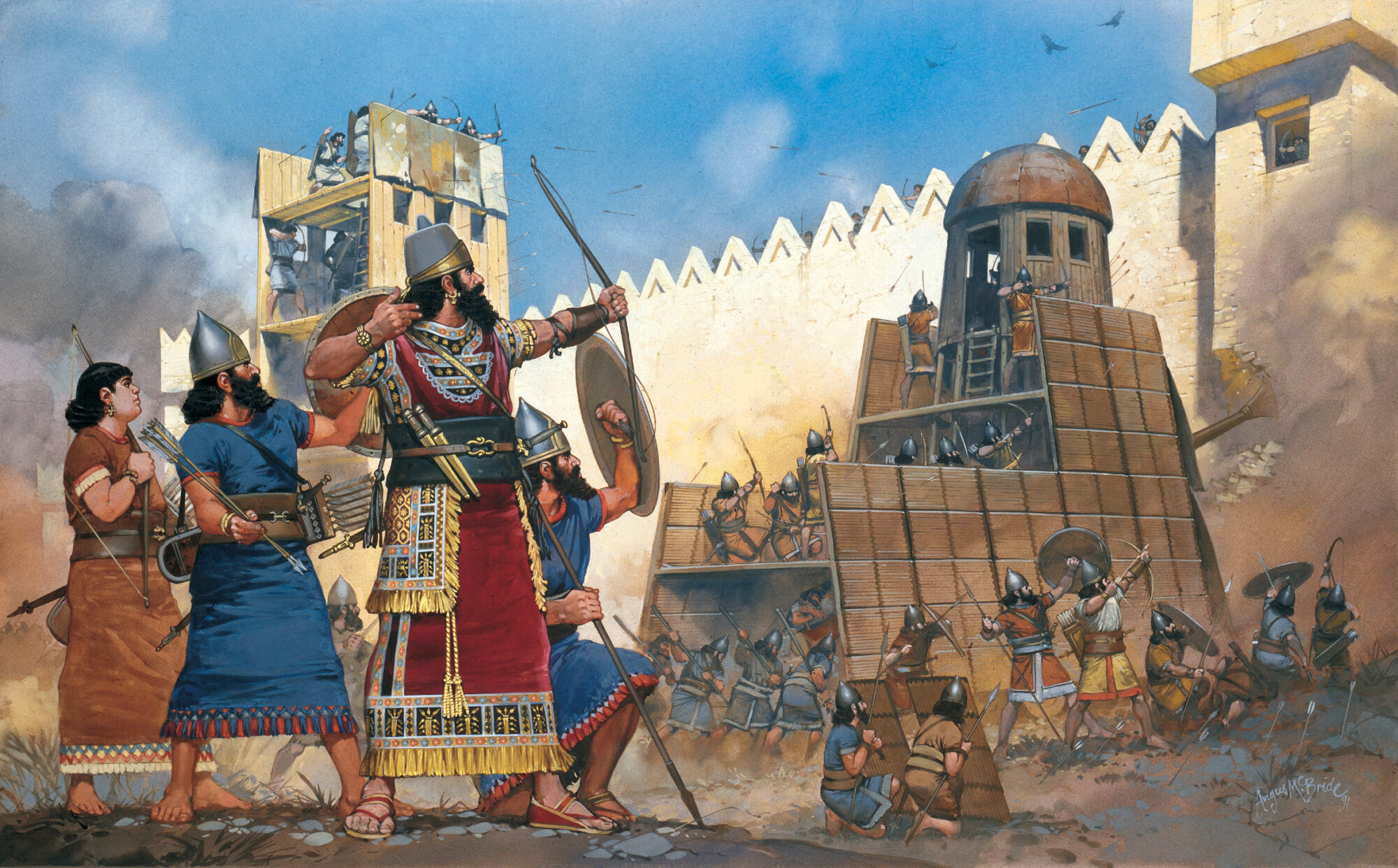

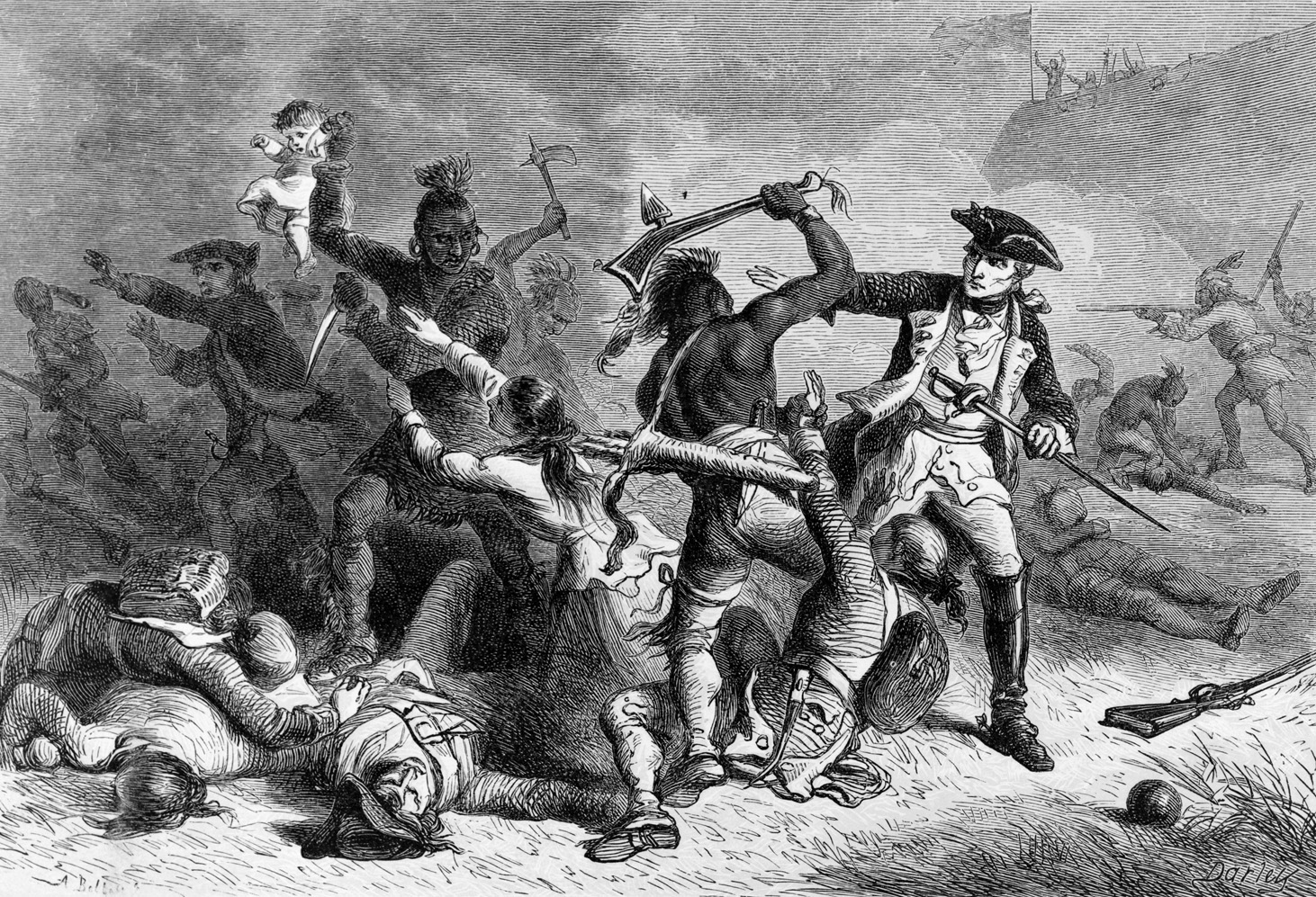

Unmistakable—that is what Angus McBride’s illustrations are. They reconstruct a past that is filled with drama and danger, as well as wonder and humor. Yet his scenes of doughty warriors and sweeping action are rendered with faithful attention to historical detail. This is an artist with the heart of a storyteller and the mind of an archaeologist and historian. An illustrator now for more than half a century, McBride has gained a worldwide following largely through his military subjects, especially with Osprey Publishing. But all aspects of life in earlier times fascinate McBride.

“I would dearly love a time machine,” he muses, “and spend an hour in the company of some of the people of the past, to see how they did things. Actually watch them at work for a while; see them sharpening their implements, preparing for war, and then come back with real-life, firsthand information. Most of what we do as historical illustrators is inferential. We pick up little details here and there, and we put them together.”

Lacking that time machine, McBride finds that his lifelong love of learning new things about practically any subject helps him to put flesh on the bones of the past. “I’m a fanatic about Egyptology,” he says. “I’m fascinated by astronomy. I read everything I can find on new advances in space travel. And archaeology generally, ancient history, prehistoric history, dinosaurs, and all that sort of thing absolutely fascinates me. I’m completely swept up. I start on one thing and I find I have to put it down and go on to something else. I have to get hold of a subject almost physically.” One way or another, much of this information finds its way into his illustrations. “I read fairly slowly, actually. It takes me a long time to get through a book, but once I’ve gotten through it I can remember for 40 years afterward what I have read, which helps.” For him, it is all grist for the mill, or rather for his art. “It is amazing how much you can work in.”

Despite his love of historical detail, what most people remember about McBride’s paintings is their impact. Martin Windrow, the respected author and editor of military subjects, once wrote,“Among his peers, Angus is known for his brilliant use of colour, his mastery of light effects and for his command of the viewer’s eye, which is directed exactly where he wants it, as soon as the page turns. He brings to these often immensely difficult reconstructions a meticulous care over the shadowy fragments of historical evidence, coupled with a flair for dramatic atmosphere and characterisation:

What one American collector has called the ‘sunset and ravens factor.’” McBride’s longtime friend and fellow illustrator, Richard Hook, echoes these views. “His lighting effects —I don’t think there is anyone to touch him. That’s what I admire. It’s nearly graphic at times. He will promote any atmosphere he wants purely with the light.”

Hook comes closer to explaining the effectiveness of McBride’s art when he states, “The other thing that I admire about Angus is that, more often than not, he pulls everything out of his head for an illustration.” Most artists will draw from whatever source material they can find that gives them the necessary information —posing themselves in mirrors, using models, or working from photographs. Often the result is a painting that is an assembly of nicely realized details, none of which add up to a fully integrated composition. McBride at times does turn to these visual aids, but he does not copy them slavishly. Rather, he processes the information through his imagination, draws on his visual memory, selects details and invents others, until all the elements of his picture work together to achieve his purpose.

McBride himself is characteristically more modest about his skills. “I am totally self-taught. I started out years behind everybody else, technically, and probably still am. I have my own methods of solving problems, but they are all rather antiquated. It’s sort of paper and string stuff. I’m not a great guy for mechanical aids. I tried airbrushing and it was a disaster. I rapidly found how to do things a different way. I’m very old-fashioned, I think, in that sense.” He once said, “I find that a painting, for me, is a series of mistakes that have been corrected from start to finish.”

Although he describes painting in oils as “sheer joy,” McBride does not like the way they reproduce in publications. And a bad experience with acrylics once keeps him working steadily with his favorite medium, opaque watercolors (also known as gouache) on illustration board. He loves their flexibility, brilliance, and ability to be either transparent or opaque.

As for his influences, there are many. “People whom I admire enormously, starting when I was a kid, obviously, include Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac. I go moggy about 19th-century narrative painters: Alma-Tadema, Gerome, David. I’m absolutely sick with admiration for them. I know it’s all very unfashionable, but it’s so beautifully done. And then some of the early 20th-century painters, like Terence Cuneo, and the war artists—Fortunino Matania, for example. To me, they are gods. I know they are all dead now, but when I kick the bucket, I’m going to make a beeline for them and ask them a few questions.”

Unlike his heroes of the art world, McBride had little formal training, and less opportunity to acquire it. Born of Highland Scots parents in London in 1931, he was orphaned by the time he was 12. Faced with the realities of life in postwar London, he sought a living in commercial art. Joining an advertising firm, where he could earn while he learned, McBride worked there for the next 13 years.

He briefly became a soldier during his two years National Service with the Royal Fusiliers. Much of his time was spent in Berlin. What he remembers most about the soldier’s life is the laughter. That, and the almost constant presence of children, dogs, and other civilians. These impressions would later influence his military art. “Almost wherever there were soldiers, there were children. They came around to watch and carry things and be useful and so on. Now, when I construct a picture, if I do it on my own bat, there’s invariably a child in it somewhere. Some little boy who is hoping to pinch somebody’s wallet, or something like that. You see, this is historically what actually happened. We tend to sanitize our militaria a little bit, as though it was all a sort of marvelous male game that nobody else was involved in. But it’s never been like that. Everybody’s been involved.”

In fact, McBride has enjoyed upsetting the “male game” notion in several past assignments where he depicted military women. These include ancient Scythians, 19th-century Ashantis, and 20th-century Israelis. “The Israeli women soldiers were tremendous fun to do, because they were sort of ‘women warriors.’ I’ve always found women extremely interesting to draw and paint anyway, and the only snag about doing a lot of military art is that you don’t often get a chance to do this.” McBride feels strongly about the role of women in history and regrets that he does not have more opportunities to illustrate it.

Returning to London in 1951, McBride worked again in advertising before seeking new opportunities in Cape Town, South Africa. While finding his way into the local commercial art field, he married his wife, Pat, and they had their first child, Ian. “I’m very fortunate,” McBride says warmly. “I’ve got a most marvelously tolerant and understanding wife. There are people in the art game who don’t have this singular blessing. They have to struggle to do what they do against the opposition of their families.” But South Africa offered few outlets to an illustrator yearning to combine his talents with his love of history. In 1961, he moved his family to England where a daughter, Fiona, was born. Back in London, Angus McBride realized his dream of becoming an historical illustrator.

He went to work at a new educational magazine for teens called Finding Out, where he was hired at almost the same time as Richard Hook. Hook, who became the magazine’s art editor, is now an internationally published historical illustrator and likewise one of Osprey’s most popular artists. He recalls those early days: “To start off with, Angus illustrated the whole of the darn magazine. He was working so solid and hard it was unbelievable. Goodness knows how much he was turning out a week.” The two began a close friendship that has lasted to this day. As Hook puts it, “We clicked from the word go.” McBride, whose experience up till then had been mostly with the kind of black and white illustration common in advertising, now found himself faced with color assignments. As he explains, he was “still experimenting, often disastrously, with techniques and visual approaches.” He remembers that it was Hook who allowed him to find his way with color by keeping the assignments coming. Hook remembers it somewhat differently: “I think Angus has always had a natural color sense. The only thing he was lacking at that initial stage was confidence. Once he got hold of that, he never let it go.”

McBride went on from Finding Out and a similar magazine, Look and Learn, to establish his reputation as a leading historical illustrator, first in England, and then abroad. In 1975, he heard about Osprey’s Men-at-Arms series from fellow illustrator Gerry Embleton. Since then, he has illustrated more than a hundred titles, with more on the way. One of these, The Zulu War, which he also authored, was published in 1976, the same year he returned with his family to South Africa.

It was with Osprey that McBride became a leading illustrator of ancient subjects. Some of the best of this work has been in association with Dr. David Nicolle, himself the son of a noted illustrator, who has also illustrated. Nicolle echoes many other authors in his praise for McBride as a collaborator. “Angus is a joy to work with. He follows my references exactly -—which is just as well as I work in England and he works in South Africa, so we don’t have much chance to make corrections. As you can of course tell, he has a terrific feeling for period, and especially for the rather exotic subjects which I prefer to write about. He has a true sense of story and drama.”

Apart from his fascination with ancient and medieval times, one reason McBride is drawn to illustrate these early armies is his love of variety. Although he admires the work of some of today’s artists who portray the American Civil War, for example, he cannot imagine himself doing line after line of men in the same uniform. Also, Angus McBride seems to prefer to paint warriors rather than soldiers. “Soldier” is an honorable word and profession, but it can suggest uniformly dressed and equipped men who stand around in groups, waiting for someone to tell them what to do. In contrast, “warriors,” as portrayed by McBride, are rugged individualists: They have spirit; they stride confidently, laugh heartily, and do their work with gusto. Even when he does illustrate uniformed soldiers, as he did in several books on Napoleonic cavalry for Osprey, he cannot bring himself to produce a mere uniform plate. He must bring out the human qualities of each uniform’s wearer—often roguish, with plenty of élan.

The good news is that Angus McBride has no plans to retire. He is already booked well into next year with assignments for Osprey and other publishers. And he certainly does not feel as if he has done all he wants to do. “I’ve got a lot of unfulfilled ambitions in illustration. I’d love to do more work on fantasy. I am fascinated by Tolkien. I am just hoping that one day somebody will ask me to do the whole of the Lord of the Rings for them.” Likewise, he wants very much to illustrate more about ancient Egypt.

He grows philosophical when speaking about the passing of his friend and fellow illustrator, Ron Embleton, some years ago. Embleton died unexpectedly, at his drawing board, with all of his assignments finished, packed, and ready for shipping. “He died in harness. That’s a consummation devoutly to be wished. I hope I can go like that.”

And how would he like to be remembered? “From generation to generation, people lose interest or gain interest in things. I understand that. Historical accuracy is a kind of thread which people occasionally lose hold of. And it’s that thread that I am primarily interested in. What actually happened? What did people really do? What did they really look like? And in that sense, I do feel occasionally that I am in the minority. I would like to be remembered for having helped to restore accuracy to historical illustration.” He is far more likely to be remembered for having kindled a love of history in generations of people with the spark of his own passion, expressed so vividly in his art.

Warriors & Warlords: The Art of Angus McBride is a collection of the very finest historical illustrations drawn by Angus McBride. Warriors & Warlords is available from Osprey Publishing from October 2002, priced $29.95. Contact Osprey Direct toll free at 1-800-826-6600 to order your copy today.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments