By Joshua Shepherd

For the Americans of 2nd Battalion, 13th Armored Regiment, their arrival at Anzio in early May 1944 was anything but heartening. The U.S. VI Corps had hugged the Italian coastline below Rome since January of that year in a steadily shrinking perimeter. The beleaguered Allies faced daily artillery bombardment from well-placed German artillery. In a desperate bid to break the stalemate, Allied supplies and reinforcements poured into the harbor on a daily basis. But after four months of bloodletting, the front lines had barely moved.

The tank crews of the 13th Armored Regiment, which was attached to the 1st Armored Division, arrived among a batch of fresh reinforcements. Allied senior commanders hoped that the influx of reinforcements would be sufficient to enable the Allies to break out of the German encirclement. Although the men of the regiment had seen hard fighting in North Africa and Italy, the sight that greeted them as they rumbled toward the front lines was a grim reminder of their deadly assignment. Peering from the turrets of their M-4 Shermans, the tankers stared quietly at tidy rows of freshly painted white crosses, which seemed to stretch to the horizon. “Our first sight as we drove inland was a shockingly large United States cemetery,” recalled Lt. Col. Henry Gardiner, the 2nd Battalion’s commander.

The costly fight for Anzio had unfolded as the Allies sought to bring the war to the European mainland. Following the liberation of Sicily in summer 1943, the Allies set in motion their plans to invade the Italian mainland. British Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army crossed the narrow Straights of Messina on September 3, 1943, but his advance ground to a halt in the face of stiff German resistance.

The U.S. Fifth Army, under the command of Lt. Gen. Mark Clark, stormed ashore at Salerno on September 9 in an amphibious assault known as Operation Avalanche. Although Clark succeeded in establishing a foothold on the Campanian coast, Generaloberst Heinrich von Vietinghoff’s 10th Army soon pinned down Clark’s two corps in a narrow beachhead. After desperate fighting that barely averted disaster, the Allies switched to the offensive after the Germans began disengaging on September 16. U.S. troops on the right of the beachhead linked up with the vanguard of the British Eighth Army advancing from the south. The Allies succeeded in capturing Naples on October 1.

These incremental successes revealed that the fight for Italy would prove to be a grinding war of attrition as German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring’s Army Group C waged a fierce fight contesting every inch of ground on the peninsula. The Allies paid dearly as they slowly battled their way north. The Allies were hampered in their use of armor by the mountainous terrain of the Italian peninsula. In many respects, the Italian campaign became a brutal slugfest between veteran forces.

The Allied advance ground to a halt in December at the formidable 100-mile Gustav Line, a belt of German fortifications that ran along the Garigliano and Sangro rivers and included the citadel of Monte Cassino, perched on a rocky crag. Making use of the dizzying warren of steep ridges, plunging ravines, and jagged peaks, German forces, among them elite German paratroopers, rendered the imposing position nearly impregnable. Facing a bloody debacle in the rugged mountains of central Italy, the exhausted Allied armies found themselves fought to a standstill.

Imaginative plans for breaking the bloody stalemate came from the highest levels. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill became the primary champion of an audacious amphibious landing behind the German lines. Both Clark and his superior officer, General Sir Harold Alexander, the commander of the Allied 15th Army Group in Italy, had considered the idea but dismissed it as an ill-advised strategic concept. However, Churchill remained committed to the idea.

Despite the reticence of his senior commanders, Churchill wielded his considerable influence in pushing for the operation. British and American strategic doctrine was likewise at loggerheads. Although Churchill favored a policy of confronting the Axis forces in the Mediterranean, the Americans preferred to save resources and manpower for a direct confrontation against the Germans in France. Not to be dissuaded, Churchill continued pushing for an invasion of Italy. “The stagnation of the whole campaign on the Italian front is becoming scandalous,” he said.

With the pending invasion of France not scheduled until summer 1944, a compromise was reached. Naval resources, including vital landing craft, would be allocated for an amphibious landing on the Italian coast before their transfer to the English Channel. Rather than batter themselves in futile frontal attacks against the Gustav Line, the Allies would launch a daring seaborne landing that would threaten German lines of communication and unhinge enemy defenses.

Discussion centered on the number of troops to be allocated for the mission. Alexander initially had thought it would take five divisions, but this number of troops, as well as the number of vessels that would be needed to transport them, was not available. Clark pushed to have at least three divisions for the amphibious operation, but in the end it was decided that just two would go ashore.

Planners settled on a somewhat unlikely locale for the landings, near the coastal town of Anzio. The town, as well as the nearby village of Nettuno, constituted an idyllic Mediterranean resort situated 34 miles southwest of Rome. The locale offered the prospect of ideal landing beaches. There were no hills overlooking the beach for the enemy to fortify. The nearest high ground, the Alban Hills, was 20 miles inland. The countryside consisted of vast, level farm fields suitable for the rapid movement of troops and armor.

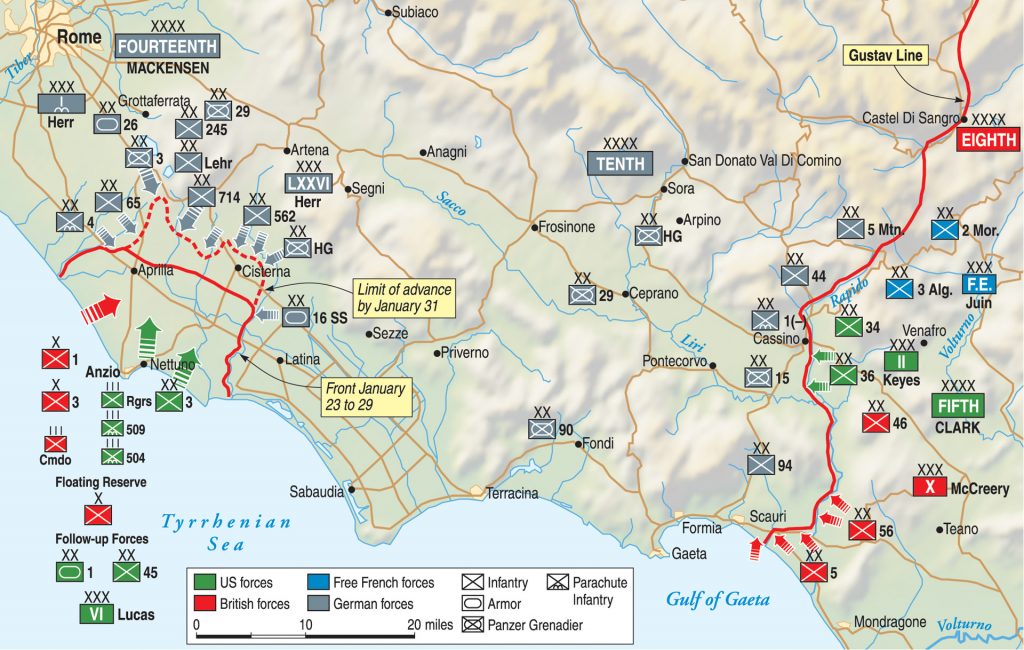

The final plan called for landing Maj. Gen. John Lucas’ VI Corps, composed of the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, the British 1st Division, and various paratrooper, ranger, and commando units. A total of 47,000 men and 5,500 vehicles would go ashore at Anzio during the first days of the invasion. The VI Corps would be reinforced by elements of the U.S. 45th and 1st Armored Divisions.

Alexander harbored serious reservations about Lucas’ suitability for such an assignment. Although Lucas possessed a sterling service record and an unquestioned reputation for personal bravery, he was a cautious tactician. Yet the operation required a hard-driving, audacious commander if it were to succeed.

For his part, Lucas was less than enthusiastic about the entire plan. With an initial landing force of two divisions, he feared that VI Corps was far too large for a simple raid, but not nearly large enough to punch through German positions and advance inland from the coast. “They will end up by putting me ashore with inadequate forces and get me in a serious jam,” he wrote in his diary.

An embarrassing pre-invasion training exercise only served to further dampen enthusiasm. Landing craft failed to hit the beaches in proper order, or landed on the wrong beach entirely, or showed up over an hour late. A dumbfounded Lucas watched from the landing beaches in mounting consternation.

Maj. Gen. Lucian Truscott, commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, sent an angry protest up the chain of command in which he voiced his objections. Clark brushed the warning aside. The landings at Anzio, codenamed Operation Shingle, had been ordered from the highest levels. The invasion would proceed as planned.

In the early morning hours of January 22, the Allied invasion fleet of 400 ships constituted an impressive sight. It comprised cruisers, destroyers, two liberty ships, 84 LSTs, 96 LSIs, and 50 LCTs. A pair of British ships pushed out from the fleet and launched a barrage of rocket fire intended to soften up German defenses.

South of Anzio, the main American landings went off without a hitch. Three regiments from Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division struck the coast along a stretch of shoreline codenamed X-Ray Beach. To the south, the 15th Infantry Regiment veered off to the right in order to anchor the American flank near the Astura River. While the 30th Infantry pushed directly inland about three miles, the 7th Infantry Regiment swung left in order to make contact with British troops farther north.

Little more than scattered gunfire greeted the elite troops tasked with seizing Anzio and Nettuno. The paratroopers of the 509th Parachute Infantry occupied Nettuno after walking unopposed into the village. Elements of the 6615th Ranger Force, commanded by Colonel William Darby, seized the port of Anzio.

Five miles to the north, the troops of the British 1st Division faced light opposition but met with unforeseen delays. After encountering an unwelcome belt of minefields, the troops balked at moving forward. Fortunately, no German counterattack was forthcoming, and the British eventually moved out after paths were cleared through the minefields. British commandos pressed forward to the Padiglione Woods, where they linked up with elements of the U.S. 7th Infantry.

safe routes through enemy minefields.

The landings had been a relatively easy affair. Lucas’ forces had succeeded in securing the beachhead and capturing 200 Germans at the cost of 13 killed and 97 wounded. By nightfall on the first day, the Allies had landed 36,000 troops, as well as 3,200 tanks and trucks.

Despite the relative ease of the initial landings, the enemy had been far from idle. The number of German troops in Italy was inadequate to defend the entire coastline, but Kesselring moved with remarkable speed to funnel reinforcements to the area once it was clear that a major landing had occurred.

To contest the Allied landing at Anzio, the German High Command sent reinforcements from as far away as France, Germany, and the Balkans. Direct command of the defenses was assigned Generaloberst Eberhard von Mackensen, commander of the German Fourteenth Army. Although Mackensen had a polyglot collection of forces, some of these units included tough veterans.

The Allies pushed inland on the second day of the invasion to expand their perimeter. In the succeeding days the two sides sparred. Lucas was wary of becoming overextended. Amid an ominous buildup of German forces, the Luftwaffe launched a series of air attacks on Allied shipping and ground forces.

Luftwaffe attacks on Allied shipping in the waters off Cape Anzio increased as reinforcements were offloaded on the beachhead. The Luftwaffe sent Messerschmitt and Focke-Wulf fighters, as well as Heinkel, Dornier, Junkers, and Stuka bombers against the Allied warships and transports. The USS Plunkett was sunk on January 24 by a direct hit from a Ju-88, with the loss of 53 hands. One of the most tragic events was the sinking of the hospital ship St. David. Luftwaffe bombers scored a direct hit that sunk the ship at the cost of 96 lives.

By January 25 the Germans had moved three divisions into place to block Allied forces advancing inland. From left to right were Generalmajor Paul Conrath’s Panzer Division Hermann Goring, Generalleutnant Fritz-Hubert Graser’s 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division, and Generalmajor Hellmuth Pfeifer’s 65th Infantry Division.

Despite heavy shelling from German artillery, elements of the British 1st Division began to push inland that day, making good progress towards the hamlet of Aprilia. The village’s bleak industrial architecture earned it the nickname of “The Factory,” a moniker soon rendered notorious for the bloodletting that would take place there. The British seized the village, but suffered badly the next day. The 29th Panzer Grenadier Regiment of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division, whose crack soldiers were veterans of the Eastern Front and Salerno, backed up by a column of Panzers, regained control of Aprilia after a furious counterattack.

By the end of the first week, Lucas had 61,000 men at his disposal, but the Germans had 71,000 men organized into 33 battatlions backed by 238 guns to oppose him. Clark began to fret that the VI Corps commander was overcautious. “Lucas must be aggressive,” wrote Clark in his diary. “He must take some chances.”

Relenting to pressure from his superiors, Lucas took his chances on the evening of January 29, implementing an ambitious plan that he hoped would crack open the German defenses. The plan called for Truscott’s 3rd Division, on the Allied right flank, to strike out for Cisterna, a crossroads that controlled Highway 7 leading to Rome. Allied intelligence had reported that the German defenses at Cisterna were tantalizingly weak and ripe for exploitation.

Lucas detailed the 1st and 3rd battalions of Rangers to spearhead the attack. They were to infiltrate enemy lines by quietly slipping up an undefended drainage ditch in order to soften up German troops in Cisterna before the main body arrived. The 4th Ranger Battalion was to seize the main road to Cisterna. The 7th and 15th infantry regiments on the left and right, respectively, would provide the main thrust for taking the town.

The clandestine infiltration of the Pantano Ditch was an operation for which the elite Rangers were uniquely suited. At 1:30 am the two battalions entered the ditch and quietly trudged through frigid muck that rendered movement agonizingly slow. Due to the difficult marching conditions, they were lightly armed with small arms, bazookas, and hand grenades. Their approach went well, though, and they crept forward undetected through the ditch.

As the first streaks of dawn lit the horizon, the Rangers had arrived at the Conca Road, about a mile from the town. Major Jack Dobson, commanding the 1st Battalion, was not encouraged by what he saw. In addition to large numbers of German infantry, it was obvious that armor was on hand as well. Unable to reach Darby by radio and with the sun coming up fast, Dobson had little choice. He issued orders for an attack toward Cisterna.

When the Rangers crossed the Conca Road, bedlam erupted. They had unknowingly walked into an enemy camp. Scattered gunfire broke the silence. Rather than easily overrunning an understrength German garrison, they had inadvertently stumbled into elements of Panzer Division Hermann Goring.

The chaotic struggle that ensued was a grim fight for survival. German fire pinned down the Rangers in a triangular olive grove that offered little cover. A half-dozen German machine-gun crews on the field’s perimeter opened up a murderous crossfire. The large-caliber bullets shredded the olive trees and killed or wounded many of the Rangers.

The situation only got worse. With little warning, a Mark IV Panzer and several self-propelled guns clanked onto the scene and opened fire. While shells crashed through the trees and machine-gun fire swept the field, the Rangers opted for the only course of action left to them: They launched a desperate counterattack into the teeth of the enemy armor.

Rushing toward the enemy armor, Rangers swarmed over the tanks. Dobson shot an enemy tank commander with his sidearm at point-blank range and then dropped a phosphorous grenade down the hatch. The explosion killed the crew inside. When a bazooka round exploded against the side of the tank, Dobson crumpled to the ground with shrapnel fragments in his hip.

The desperate fight was far from over. The Germans drove back the Rangers, who split up into small groups as unit cohesion broke down. As the Americans slowly ran out of ammunition, isolated knots of demoralized men began to surrender. But on a chaotic battlefield with a fluid front line, more horrors awaited.

When a column of captured men trudged toward Cisterna, die-hard Rangers concealed nearby opened fire on the German guards. Some prisoners were bayoneted, others cut down by friendly fire. Startled and furious German troops dove for cover, and then opened fire on the prisoners.

The final Ranger holdouts, fortified in an Italian farmhouse, fought on into the afternoon. In the final terrifying moments, Darby was finally able to reach his beleaguered men by radio. Speaking to Sgt. Major Robert Ehalt, Darby encouraged his troops as best he could, advising Ehalt to gather as many men as he could and cut their way out. It was far too late for such an attempt, however. As German troops began to overwhelm the last defenders of the farmhouse, Ehalt resigned himself to whatever fate held for him. “So long, colonel,” he said, “maybe when it’s all over I’ll see you again.”

When his staff left his office, a devasted Darby lay over his desk and wept. And for good reason; the crack force of rangers that he had trained and served with since North Africa had been virtually wiped out. About 450 men had been captured, the balance killed or wounded. Of the 767 rangers who had gone into action behind German lines, only six made it to the safety of American lines.

The main American thrust, which was intended to link up with the rangers at Cisterna, fared almost as badly. The 4th Ranger Battalion, which moved out to relieve their fellow Rangers, was badly mauled against stiff German resistance and suffered 50 percent casualties. The Germans also chewed up the 7th and 15th infantry regiments during their advance. After all the bloodletting, the Allied frontline had advanced barely a mile.

While the Americans met with disaster, the British 1st Division in the beachhead’s northern sector drove hard along the Via Anziate. But the British advance stalled in the face of the German 1st Parachute Corps’ determined defense of Aprilia. Bloody fighting ensued over the next two days, each side bludgeoning the other in a brutal clash that saw the British take Aprilia but come up short in seizing the vital road junction at Compoleone. To their credit, the British succeeded in plunging over two miles deep into the German lines, tenuously occupying a narrow bulge that was badly exposed to a German counterattack.

Both sides were left badly shaken by the fierce fighting, but there would be little rest. Reinforcements were funneled to the beachhead to replace battle losses. The British received an additional brigade of infantry, and the Americans were assigned the 1st Special Service Force to fill the gap left by the Rangers. Although Alexander and Clark had both hoped for a renewed push inland, it was obvious that Lucas’ demoralized VI Corps would have to entrench and brace for the inevitable German counterattack.

That attack fell with grim fury on February 3. The German target, not surprisingly, was the badly overextended British bulge known as “the thumb.” In the midst of a driving rain, a determined German attack nearly cut off the British 3rd Brigade at the tip of the thumb. Although the troops were extricated from the trap, the British were forced to pull back and consolidate around the shattered ruins of the factory of Aprilia. In a single day’s fighting, the British suffered 1,400 casualties.

Mackensen opened a fresh attack on the evening of February 7, throwing even greater weight at Aprilia. During two days of horrific fighting, the Germans succeeded in capturing the town and driving the 1st Division out of the thumb. The fighting had decimated both sides. The British were down to 50 percent effectives, and the Germans had captured a staggering 2,500 men.

With the British in desperate need of relief, Lucas sent in American troops to take over the fight. On the morning of February 11, the 1st Battalion of the 179th Infantry Regiment, part of Lucas’ reserve 45th Infantry Division, attacked the German defenders of the factory, ushering in two days of bloody combat. Backed up by Shermans of the 191st Tank Battalion, the Americans succeeded in prying the enemy loose from the edge of Aprilia. But dogged German counterattacks proved impossible to beat off, and the 179th was forced to abandon the town, by then reduced to rubble, to enemy hands.

With the Allies pushed south of Cisterna and Aprilia, Lucas’ beleaguered troops were penned into a compact salient surrounding Anzio. Mackensen possessed a preponderance of heavy guns, and he would make the most of it. The Germans ringed Anzio with 370 pieces of artillery, dropping an unrelenting hail of iron on the beachhead. Allied artillery replied in kind, but with so many troops crowded into the Anzio perimeter, German gunners enjoyed a plethora of exposed targets.

Terrified Allied troops dug crude bunkers as best they could, and the beachhead soon resembled a vast maze of burrows. German artillery fire, including massive rounds fired from a 283mm Krupp K5 railway gun that the Allies named “Anzio Annie,” continued to range the beachhead.

Having seized the initiative from Lucas, Mackensen was eager to maintain pressure on the hard-pressed defenders of Anzio. Although the general preferred a measured approach, he was compelled to develop a more aggressive plan. At German leader Adolf Hitler’s insistence, a major attack was launched in an attempt to smash Allied defenses and drive them all the way to the coast.

Codenamed Operation Fischfang (Fish Haul), the German offensive aimed at nothing less than the destruction of the VI Corps. Kesselring and Mackensen considered such an ambitious attack impractical, for their units could not afford the heavy casualties that would be incurred. Despite their reservations, the attack was carried out on February 16. Under the cover of an enormous artillery barrage, Mackensen’s 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division pushed west along the Via Anziate into positions occupied by the 45th Infantry Division. At the initial point of attack, Mackensen had effectively massed his assault formations and enjoyed a three-to-one numerical advantage.

Although sorely pressed, the Americans gave a good accounting of themselves. Allied artillery possessed vast stockpiles of ammunition that was used to brutal effect. American gunners worked feverishly to lay down a deadly wall of fire in support of the foot soldiers of the 157th and 179th infantry regiments holding on at the front. The two regiments occupied either side of the Via Anziate at the center of the maelstrom.

American armor, including tank destroyers, also moved up in support. German units were forced to operate in the open and paid dearly for it. The sharply dressed troops of the Infantry Lehr Regiment, a training outfit favored by Hitler, broke in confusion and scattered for the rear. German tanks, which struggled to move due to excessively muddy conditions, also suffered heavily after bunching up on available roadways.

Despite heavy casualties, the Germans got the better of the fight, driving a hole in the American front line nearly a mile deep. Mackensen also launched diversionary attacks all along the front, probing for weak spots in Truscott’s 3rd Division and the British 56th Division. Such halfhearted attacks proved costly, though, and Mackensen’s infantry suffered dearly. The Germans sustained 1,600 casualties in the costliest day they had yet experienced at Anzio.

But the bloodletting was far from over. Once committed to the offensive, Mackensen was obligated to see it through. Small German teams succeeded in infiltrating the American lines that evening, and in the morning they were followed up with another infantry attack that targeted the battered troops holding the Via Anziate. Three German regiments and about 60 tanks drove a wedge in the American lines and plunged through the gap for another mile.

In order to plug the dangerous hole in his line, Lucas responded with everything he had, ordering artillery, air strikes, and naval guns to hammer the advancing Germans. He also sent in three reserve companies from the 1st Armored Division. In the event of disaster, Lucas placed the remains of the British 1st Division in a last-ditch defensive line behind the hard-pressed Americans.

Senseless killing continued for days, but a determined American defense increasingly took the starch out of the German offensive. Some of Mackensen’s lead assault columns suffered 70 percent casualties. Consistent and effective Allied artillery was a key ingredient to fending off the enemy attacks. One advancing German unit, thought to exceed 2,500 men, was caught in the open and virtually annihilated by a devastating artillery barrage.

As the strength of the offensive slowly subsided, both sides were eager for a respite from the killing. The two sides had savaged each other during four days of unrelenting carnage, and during the wake of the battle, fatigue parties warily scoured the field in search of the dead and dying. The muddy landscape was a macabre spectacle of churned earth and wrecked bodies. Mackensen’s operation had resulted in 5,389 German casualties, which were losses that the Nazi war machine could ill afford. The Allies suffered 3,500 casualties in the fight.

After nearly a month of frustrating and costly reverses, the VI Corps command structure was in for a sudden shakeup. Clark arrived at Anzio on February 22 to carry out an extremely disagreeable mission. Due to prodding from the highest levels, Clark had been ordered to sack Lucas.

Clark had argued in vain to keep Lucas on the job, but with mounting casualties and little to show for it, his removal became inevitable. Lucas was stung by the decision but not surprised. True to his fears from the outset of the campaign, Lucas had paid the price for decisions that had been made from the comfortable vantage point of London.

Alexander and Clark at least made a good choice in selecting Lucas’ replacement. They chose Truscott. As the new commander of the VI Corps, he had direct control of all of the Allied forces at Anzio. Although Truscott confessed, in his words, “his own inadequacy” for such a responsibility, he was well suited for the assignment. Truscott was an aggressive field commander who remained mindful of the welfare of his men.

But for Truscott there would be no honeymoon period at the head of the VI Corps. Mackensen, with few choices available, decided to launch another all-out attack before the Allied buildup of men and materiel rendered the outcome of the campaign all but inevitable. Having tried his luck unsuccessfully against the Allied center, the general opted to strike the Allied right, primarily targeting the 3rd Infantry Division, which was anchoring Truscott’s flank near the Mussolini Canal. For the attack, codenamed Operation Escapade, Mackensen scraped together five understrength divisions.

Mackensen unleashed his troops yet again on February 29 in the hope of overwhelming the fatigued Americans. Truscott, though, anticipated the attack and marshaled all available Allied artillery against it. Trudging forward through fields rendered nearly impassable due to unrelenting heavy rains, German columns were rent by the overwhelming bombardment. German troops were stopped cold. Maj. Gen. John “Iron Mike” O’Daniel, who had succeeded Truscott as commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, was pleased to note that his men did not yield an inch.

Farther to the left, though, Panzer Grenadier Regiment 1028, which had been attached to the 715th Infantry Division of the I Parachute Corps, succeeded in breaching the American line, caving in the front of the 509th Parachute Battalion and plunging nearly 900 yards into the rear areas. Startled American mortar crews grabbed small arms and fought back, stalling the Grenadiers.

By the following morning, Americans from the 2nd Battalion of the 30th Infantry Regiment counterattacked the Panzer Grenadiers, driving them off and regaining the lost ground. To their right, lightly armed foot soldiers from the 7th Infantry Regiment waged a desperate fight against Panzer IVs and Panzer VI Tigers from the 26th Panzer Division. Despite an overwhelming advantage in firepower, the German tanks made little progress. Muddy conditions, paired with a curtain of American artillery fire, kept the Germans at bay. By the end of the second day’s fighting, Mackensen was forced to call off major offensive action.

In the aftermath of the failed attack, strategic initiative had clearly slipped from Mackensen’s grasp. After the horrific losses sustained in three major offensives, the Germans were in no position to supply more reinforcements. Truscott sensed a turning of the tide, but realized that any breakout from the Anzio beachhead would be an agonizingly slow process. Mackensen’s 14th Army was a badly wounded but still dangerous foe.

With neither side in a position to launch a major attack, both Mackensen and Truscott attempted to rebuild their shattered armies. Two of Mackensen’s most reliable outfits, Panzer Division Hermann Goring of the LXXVI Panzer Corps and the 114th Jager Division of the I Parachute Corps, were sent to rear areas in order to refit. The Fourteenth Army was increasingly reinforced with raw conscripts or even Italian auxiliaries. But Mackensen’s force still contained a solid core of seasoned veterans, and his ranks swelled to 135,000 men.

Truscott’s VI Corps also experienced a dramatic reshuffling. O’Daniel’s battered 3rd Infantry Division was rotated to the reserve and replaced on the front lines by the newly arrived 34th Infantry Division. British commandos and paratroopers were pulled out of the beachhead, and the British 5th Division took the place of the exhausted 56th Division. Truscott was left with a half dozen divisions and a comfortable numerical superiority.

Unfortunately, Truscott would be unable to actually wield those forces to good effect. Amid a terrain transformed into a morass by heavy spring rains, both sides were unable to consider a major fight and continued to dig in. The horror of major combat operations temporarily subsided, but the common soldiers would endure a miserable existence in flooded trenches, where they remained under the constant threat of artillery fire and enemy raids.

Not surprisingly, morale plummeted among the Allies. For nearly three months, the troops at Anzio endured some of the most dismal field conditions of the war. The experience was hauntingly reminiscent of the hellish trench warfare of the Great War. With a measure of biting sarcasm, American wags invented a new term, “Sitzkrieg,” to describe the tactical lethargy that gripped the beachhead.

Plans for a renewed offensive, however, were in the works. The landings at Anzio had initially been carried out in order to precipitate an Allied breakthrough of the Gustav Line farther south. Allied senior planners had hoped that the Germans would be so alarmed by the Anzio landing that they would withdraw north, but Kesselring had used his reserves wisely in the first part of 1944 to not only hold the Gustav Line, but also pin the Allies on the Anzio beachhead. Ironically, it would take Allied success at the Gustav Line in order to facilitate a breakout at Anzio.

As the Allied senior commanders studied the maps, they developed a strategy that was mutually supporting for the troops at Anzio and those confronting the Gustav Line. While Allied troops smashed their way through the Gustav Line and drove north, Truscott would strike the lightly defended German lines on his right. After seizing Highway 7 and Cisterna, Truscott would push his way northeast through the Velletri Gap before taking Valmontone, a small town that sat astride Highway 6.

That thoroughfare was a major supply artery, as well as primary escape route, for enemy troops on the Gustav Line. If Truscott could block Highway 6, there was a good chance that much of the German 10th Army retreating from the Gustav Line would be trapped in a deadly pincers and destroyed in detail. Appropriately enough, Truscott’s proposed stampede for Valmontone was codenamed Operation Buffalo.

Late on the evening of May 11, Clark’s Fifth Army, paired with the British Eighth Army, lunged at the Gustav Line in the largest Allied operation to date in Italy. After a week of heavy fighting, Allied troops broke through the mountains around Cassino and crossed the Garigliano River near the coast. In a desperate gamble, Field Marshall Kesselring shifted some of Mackensen’s reserves south in order to shore up defenses there.

By May 23, it was obvious that the time was right for Allied troops to break out at Anzio. Early that morning, Allied guns opened up on German troops defending Cisterna, and Truscott followed up the barrage with an all-out attack. While British troops and the U.S. 45th Division attacked on the left and center in order to keep the Germans off balance, the main thrust targeted Cisterna. Elite troops from the 1st Special Service Force blocked Highway 7 south of the town while tanks from the 1st Armored Division smashed the defending German 362nd Division. Two days later, the 3rd Infantry Division pitched into Cisterna, brushing aside German defenses in savage fighting in the streets that left the town in ruins.

With Cisterna in Allied hands, the 1st Armored Division drove hard for Highway 6, the ultimate target of Operation Buffalo. But just as quickly as he seemed within reach of his objective, Truscott had the rug pulled out from under him.

Clark, without consulting Alexander or Truscott, abruptly ordered Operation Buffalo canceled on May 26. In a brazen move to capture Rome before British troops had a chance to get there first, Clark ordered Truscott to wheel the VI Corps to the left and drive north to the Italian capital. Truscott and his subordinates were flabbergasted by the decision. They vehemently protested the order, but to no avail. Such a maneuver in the face of the enemy was inherently risky, but Clark remained adamant. The massive pivot toward Rome would commence immediately.

By that time, the Allies’ overwhelming superiority in men and materiel was at last beginning to bear fruit. As the Fifth and Eighth Armies hammered their way north and the VI Corps threatened their flank, German forces across the peninsula were on the defensive. German defenses began to crumble on June 1 as Truscott’s troops forced their way through a gap in the Alban Hills and into the open ground beyond. With Allied armor barreling north along Highways 6 and 7, Kesselring ordered the evacuation of Rome.

Victorious American columns thundered into the city center on June 5 to the cheers of grateful Italian civilians. German rear-guard troops were pushed out of the northern suburbs, and elated G.I.’s were feted with food and wine. It was the first Axis capital liberated by the Allies, but the glory was short-lived. Following the Allied landings in Normandy on June 6, the exploits of victorious American troops in Italy were given short shrift by the press. “They didn’t even let us have the newspaper headlines for the fall of Rome for one day,” said Clark.

That abrupt exclusion from the limelight characterized the fortunes of the average soldiers who suffered, bled, and died in the nightmarish ordeal known as Anzio. Long overshadowed by more dramatic events in northern Europe and the Pacific, the grinding war of attrition at the Anzio beachhead was perhaps less glamorous but no less heroic.

Months of fighting had taken a grim toll. While in command, Lucas had estimated that he would suffer 9,000 casualties per month. His estimate was not far from the mark. The Allies suffered 7,000 killed and 36,000 wounded or missing. Trench foot disabled thousands of survivors who had endured flooded foxholes and trenches for weeks on end. The Germans fared horribly as well, suffering 5,000 killed and 35,000 wounded or captured.

Lucas would tragically remain a scapegoat for the entire fiasco, but the Allied high command realized that culpability for the disaster lay higher up the chain of command. Alexander glumly admitted that Allied planners had simply hoped for too much too soon, and tried to effect it with too little. “We wanted a breakthrough and a complete answer inside a week,” he said, adding that once forward momentum was halted, “it became a question of slogging.” British General Charles Richardson, who was Clark’s deputy chief of staff, was even blunter in his assessment. “Anzio was a complete nonsense from its inception,” he wrote.

In the wake of the bloody debacle, even Churchill was forced to acknowledge that the entire operation had been ill-advised. Although his admission was cold comfort for the American and British soldiers who had endured the horror of the beachhead, Churchill took the responsibility for the debacle. “Anzio was my worst moment of the war,” he wrote. “I had the most to do with it.”