By Peter Kross

Nations have often pressed unsavory characters and criminals into service during wartime, rationalizing that such action is in the best interest of the country during extraordinary times.

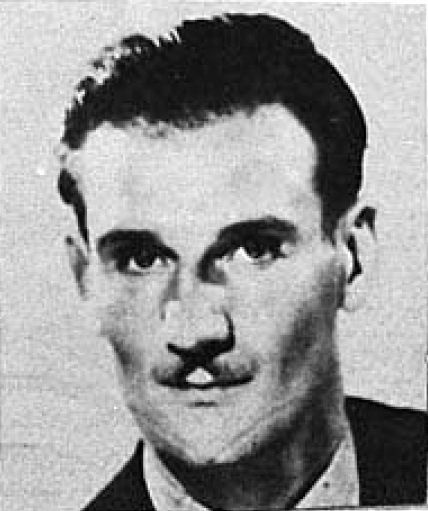

During World War II, the British Secret Intelligence Service enlisted a petty thief, con man, accomplished burglar, and man of adventure named Edward “Eddie” Chapman to act as a double agent against the Germans. After the passage of time, it is still not clear where Chapman’s true loyalties lay. Did he help his native Britain out of loyalty to crown and country, or was he so devoted to his German spymasters on a strictly personal basis that he would do anything they asked of him to save his own skin?

For students of espionage during World War II, the name Eddie Chapman was initially not as well known as other spies such as Elyesa Bazna aka Cicero, Richard Sorge, and Juan Pujol Garcia aka Garbo. However, all that changed when MI-5, the British Intelligence Service, finally released 1,800 previously classified papers on Eddie Chapman’s role as a double agent during World War II to the British National Archives. Some of these materials were also placed in the U.S. National Archives in College Park, Maryland, and are now open for public inspection.

What these documents reveal is a deeply flawed man, a womanizer who had a child out of wedlock while having affairs with other women for whom he deeply cared. They tell a story of a man who was wined and dined by two rival intelligence services, the German Abwehr headed by Admiral Wilhelm Canaris and the British Intelligence Service, which also used Chapman for its own ends. For its part, the Abwehr sent Chapman on an intelligence mission by parachute into Great Britain with a bundle of clearly labeled German marks. On the British side, they cared for Chapman’s every personal whim while they dispatched two plainclothes policemen to live with him 24 hours a day.

A Member of the Jelly Gang

Eddie Chapman was born the eldest of three children on November 16, 1914, in the English village of Brunopfield. His father ran a local pub called the Clippership in the town of Roker. The establishment did not fare very well, as the elder Chapman was prone to drink more than work.

At age 17, Eddie joined the Army, entering the Second Battalion of the Coldstream Guards. After spending nine months in uniform, he was granted leave and made a beeline to London where he proceeded to meet lovely English ladies, and more important, went AWOL. He was eventually arrested and spent more than two months in the stockade. After his release, he was dishonorably discharged from the Army, and returned to the Soho district of London, where he began his new career as a petty criminal.

He took on any job available, often working as a barman, an extra in motion pictures, a dancer, a wrestler, and anything else that could keep him in booze and women. He spent most of his free time at a bar called Smokey Joe’s where he met all sorts of crooks and quickly gravitated to the criminal underworld. During the 1930s, Chapman began his second career, breaking into homes and stealing whatever valuables he could find and forging checks. For his crimes, he was given light sentences and served a two-month jail term for stealing a check and for fraud. He no sooner was out of jail than he was rearrested for trespassing and locked up for an additional three months.

During this same period, Chapman joined a ruthless bunch of criminals called the Jelly Gang, whose modus operandi focused on the use of high explosives to break into safes. The leader of the Jelly Gang was Jimmy Hunt, whom Chapman later used in his bogus schemes to fool the Germans during the war. The Jelly Gang proceeded to rob various upscale stores in London, most notably Isobel’s, a furrier from which they stole a number of minks and capes valued at 200 pounds. Next was a pawnbroker where the gang blew open four safes, stealing 15,000 pounds. Chapman was so pleased with his handiwork that he clipped newspaper accounts of his robberies and filed them away in a scrapbook.

In 1939, with the police hot on their trail, the members of the Jelly Gang fled toward Scotland where their luck finally ran out. While trying to rob the headquarters of the Edinburgh Cooperative Society, Chapman and four others were caught by a passing policeman who heard noise and investigated. Before they could stand trial, however, the four men escaped and fled to the wilds of Jersey in the Channel Islands.

Chapman was the subject of a huge manhunt across the marshes of Jersey before finally being captured by the police while he was staying at the Hotel de la Plage. Accompanying Chapman to Jersey was his girlfriend, Betty Farmer. Eddie was locked in a Jersey jail without any means of escape. As fate would have it, however, an event soon took place that changed his life forever.

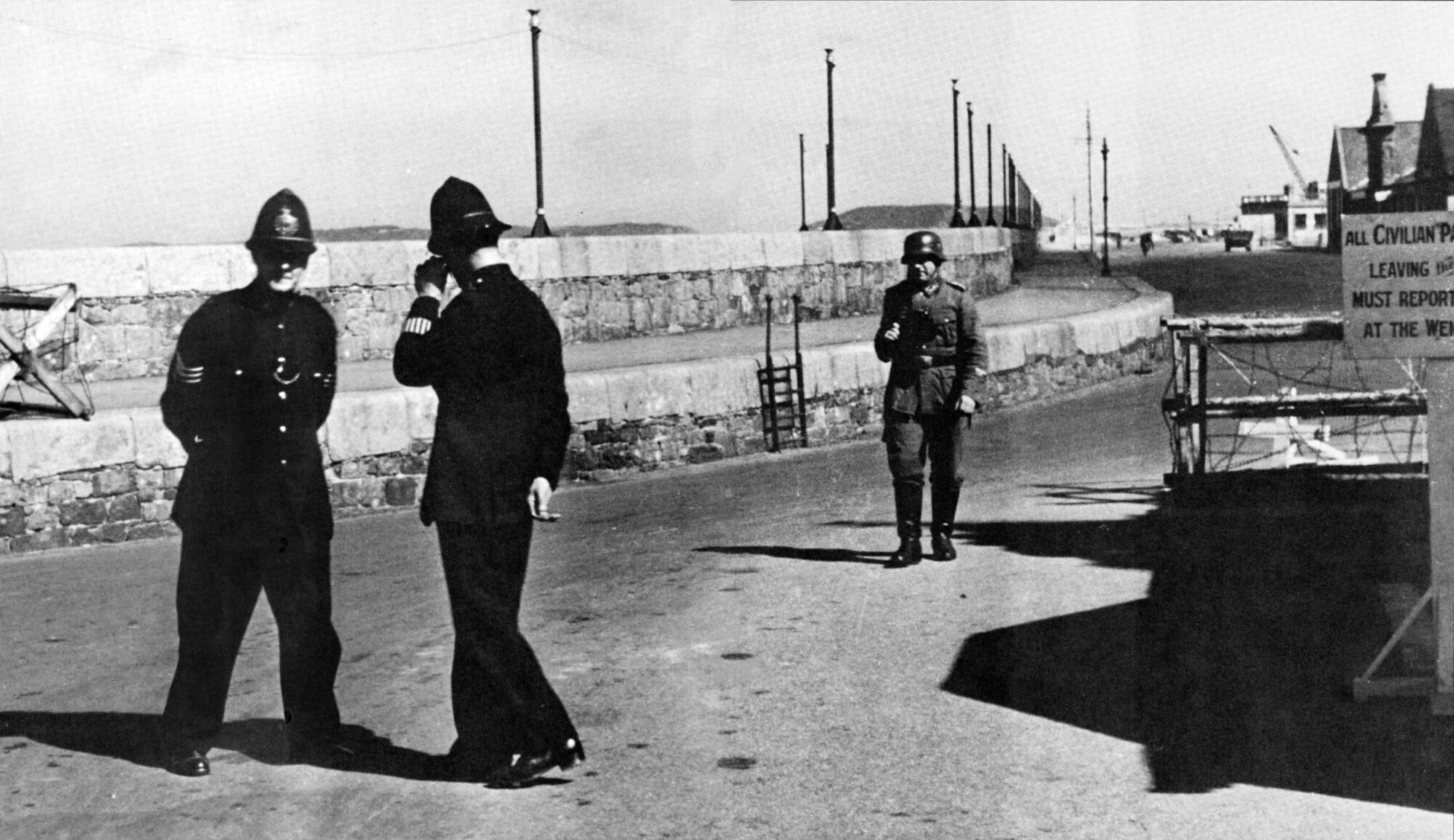

Released by the Germans

By June 1940, while Chapman was safely in jail, the German war machine was victorious across Europe. France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg were securely under Hitler’s dominion. In preparation for the anticipated invasion of Great Britain, the Luftwaffe began attacks on the outlying areas, including the Channel Islands, which became the only sovereign territory of the British Isles occupied by the Germans during the war. German troops soon overran Jersey, and the prisoners now became the responsibility of the German government.

While locked up, Chapman made friends with a 22-year-old fellow prisoner named Anthony Faramus, and the two followed each other’s whereabouts until the end of the war.

Chapman’s luck changed when he was released from prison on October 15, 1941. His buddy Faramus had been released a few months before, and both men found their new freedom intoxicating. They started a small business together, a barber shop that catered mostly to German officers and enlisted men. They also made friends with a British citizen named Douglas Stirling who was into the black market, selling whatever illicit goods he could find. The trio went into business together, operating under the table, making a good living by persuading others to buy their stolen goods.

A Spy for the Germans

Just when Chapman thought he was free from German observation, a freak accident changed his life. One day he was involved in a bicycle accident with a German motorist. Chapman was riding on the wrong side of the road and car and bike collided. Chapman was interrogated by the Germans, who warned him not to get into any further trouble. Fearing for their long-term safety, Chapman, Faramus, and Stirling decided to write a letter to the German authorities in the Channel Islands offering to act as spies for the Third Reich. Writing later of his decision to work for the Germans, Chapman said, “If I could work a bluff with the Germans, I could probably be sent over to Britain. Perhaps it was phony talk even then, and I don’t pretend there were no other motives in the plans I began to turn over in my mind. They did not occur to me either, in one moment, or in one mood.”

Chapman and Faramus wrote a letter offering their services to the commander of German forces in the Channel Islands, General Otto von Stulpnagel. Chapman also had a brief meeting with a German officer who heard his story and then promptly said he would get back to him. Weeks passed before Chapman heard from the German authorities. When he did, however, he was not happy.

Both Chapman and Faramus were arrested on bogus charges that they had cut telephone lines in the Channel Islands. They were put on a train bound for Paris, headed to an uncertain fate.

The two were taken to a prison called Fort de Romainville on the outskirts of Paris. In time, Chapman was interrogated by members of the prison staff about his previous criminal activities. One of these men was Dr. Stephan Graumann, who also went by the name von Groning. Over time, Chapman and Graumann became close personal friends despite the fact that they were on different sides of the war.

It was during these sessions that Graumann made Eddie an offer he could not refuse. In exchange for his freedom and a handsome payday, Eddie would be sent back to Britain by German intelligence to complete certain clandestine missions that he would be told about at a later date. Seeing a chance to get out of jail and return to Great Britain, Chapman volunteered to act as a spy for the Germans. He did so out of complete vanity, accepting a once-in- a-lifetime offer.

Turning Himself In

While Faramus remained in jail and eventually wound up in a concentration camp but survived the war, Chapman was taken to his new training facility, the Villa de la Bretonniere in Nantes, France. The living conditions at the villa were luxurious. He was given a crash course in the fine art of espionage, concentrating on wireless operations, hand-to-hand combat, and the use of secret ink. His training lasted about three months under the direction of Lieutenant Walter Praetorius aka Thomas, and Karl Barton, aka Herman Wojch. Soon, Chapman was adept in all sorts of clandestine arts and was ready to take the next step for his new German masters.

(Library of Congress)

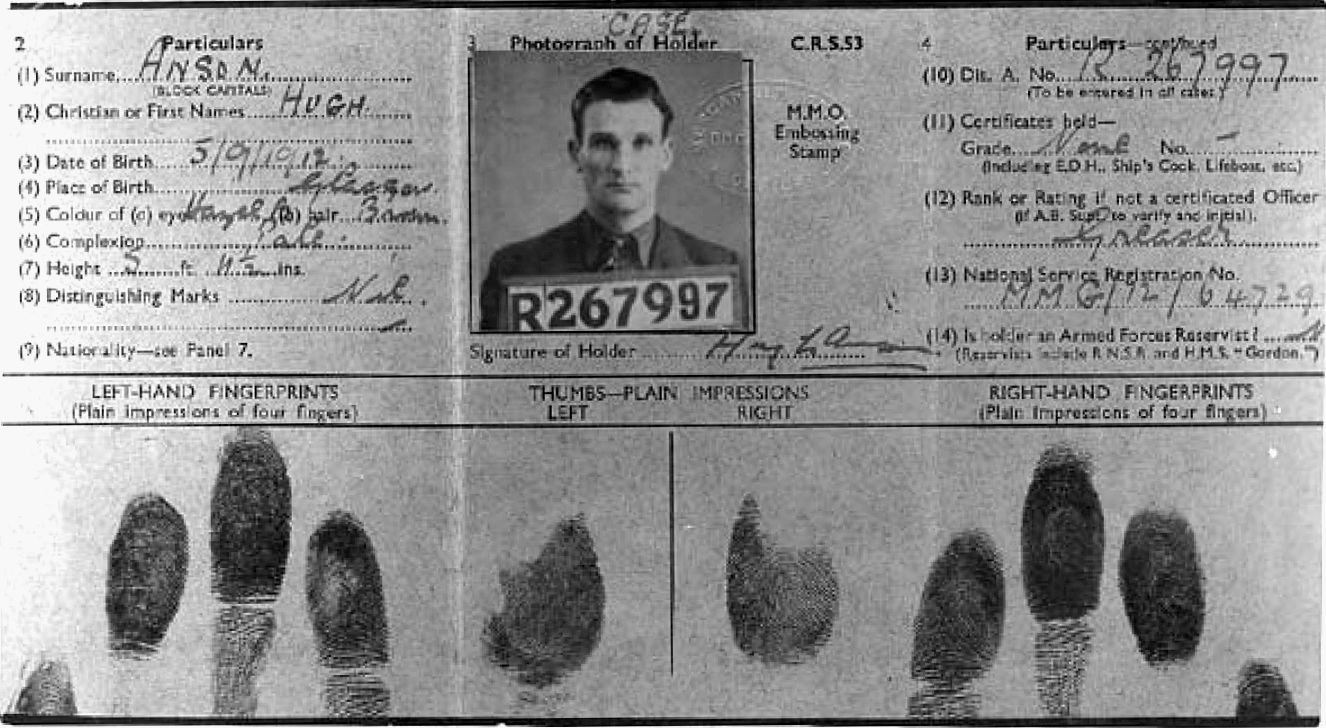

For months, the Germans had intended to send someone to Britain in an undercover capacity. When they found Chapman they believed their fondest wishes had come true. They gave their new recruit his own number, V-6523, as well as his own code name, Fritzchen (Little Fritz). He was now ready for his first assignment. On the night of December 16, 1942, carrying a radio transmitter, pistol, a bottle of invisible ink, and a cyanide pill, Eddie parachuted from a plane over the English town of Cambridge. When he landed and checked his possessions, he realized that he was given a large sum of money with the German stamp clearly visible and wrapped around the bills.

Unknown to the Abwehr and Eddie Chapman, the British knew all about his plans to enter Britain but did not yet know his exact identity. The British were able to read German cables via their Ultra decryptions of German radio traffic and tracked German agents arriving on English shores. Using their Twenty Committee or Double Cross Organization, the British were able to arrest and “turn” German spies who then operated against their former masters under the penalty of death. Most of these spies cooperated with the British to save their own lives.

Upon landing, Chapman turned himself over to the local police who called in the Secret Intelligence Service. Chapman told them the story of being recruited by the Abwehr and offered to work for the British instead.

For the men of MI-5, Chapman was an ideal candidate to double cross. He was wanted for various and sundry crimes that had taken place on British soil, and they now had him over a barrel. He could either work with the British, feeding false information to the Abwehr, or he could spend a considerable amount of time in jail. Chapman opted for the first choice and decided to work with his fellow countrymen.

From Double-Cross to Iron Cross

Chapman was sent to a secret installation dubbed Camp 020, where all captured German agents were kept. The official name of the location was Latchmere House, a large, rambling home near Ham Common in West London. It was here that Eddie would be taught the intricacies of British tradecraft and then sent on future assignments.

Chapman told his interrogators that the primary mission given him by the Abwehr was to destroy the De Havilland aircraft works that built the agile Mosquito aircraft. The Mosquito was made of wood, which gave it tremendous speed and maneuverability. His job was to blow up the factory, which was located in Hatfield, Hertfordshire.

The British, with a little help from a magician named Jasper Maskelyne, allowed Chapman to pretend that he had blown up the Mosquito factory. Maskelyne came from a family known for its magical talent. During the war, Maskelyne helped the British fool the Germans by “hiding” the Suez Canal and deceiving the enemy during the Battle of El Alamein.

Maskelyne worked closely with various components of the British military, including the Air Ministry’s camouflage section, to create a false set of explosions that, when viewed by German reconnaissance aircraft, would look like the De Havilland plant had been destroyed. Maskelyne and his crew erected fake tarpaulins to create the aura of complete devastation at the Mosquito plant. Chapman did his part, sending a wireless message to the Abwehr using his prearranged code that all had gone well. He wrote, “FFFFF WALTER BLOWN IN TWO PLACES.” When Graumann heard the good news, he sent a congratulatory message to his favorite spy. To completely fool the Germans, the British arranged for a false news item about the “destruction” of the De Havilland factory to be published in the London Daily Express edition of February 1, 1943. The paper reached Graumann via Lisbon, and he read with interest how well his master spy had done. For his exceptional work, the German government awarded Eddie Chapman the Iron Cross.

The Zigzag Case

Chapman’s superiors and teachers at Camp 020 were some of the most important members of the British Secret Service. Among them were Colonel Robin “Tin Eye” Stephens, the commander of the base; Lord Victor Rothschild, a scientist who helped Eddie with explosive techniques; and Captain Ronnie Reed, who was an expert in wireless radios. One British officer, however, wanted nothing to do with Chapman. Major Michael Ryde was, in spy parlance, Chapman’s case officer, and the two of them took an instant dislike to each other. Ryde did not like the fact that Chapman was a drunk who loved to frequent the bars in London seeking out prostitutes. He said that Chapman “seemed most discontented at the moment; he was expansive, moody, and certainly disreputable.“ Ryde wrote to Thomas Robertson, who babysat Chapman throughout the latter’s stay in England, “The Zigzag case must be closed down at the earliest possible moment.” Ryde’s superiors quickly made him see things differently.

When he was not plying his secret trade, Chapman found time to woo a number of women, all of whom he cared for very much. He fell for a beautiful Norwegian, who was also a German agent, named Dagmar Lahlum, and he worked with her when he was sent to Norway by Graumann. He later confided to Dagmar that he was a British agent, a confession that she kept to herself. Another sweetheart was Freda Stevenson, who had a baby—named Diane—with Eddie. After the war ended, Eddie married Betty Farmer, whom he had abandoned at the Hotel de la Plage in Jersey several years earlier.

When the Abwehr ordered Chapman to return to Germany, he did so with the blessing of the British government. He then spent some time at a spy school in Oslo, Norway, where he met Dagmar and learned how to sail a yacht.

At one point, Chapman offered his services to kill Adolf Hitler by exploding a bomb while he attended a rally. It seems that Dr. Graumann offered to take Chapman to one of Hitler’s rallies and obtain a seat in the front row for him. Was Graumann, who did not like Hitler or the Nazis, offering up Chapman as an assassin who would surely die in any attempt on Hitler’s life? When he told Ronnie Reed of his plan, Reed told him that it would almost certainly lead to his own death. Chapman responded, “Ah, but what a way out.”

The Zigzag case was made known to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill via Duff Cooper, who was a leading member of the intelligence establishment. Cooper said that he had discussed Zigzag at some length with the prime minister who showed considerable interest in the case.

Agent Zigzag Retires

In 1944, Graumann told Chapman that he was going to be sent back to England on another intelligence mission. The Abwehr still did not realize that Chapman was working for British intelligence, and Chapman’s new assignment was to learn as much as he could about Britain’s latest efforts to track German U-boats. He was also to obtain, if possible, the apparatus used by the Royal Air Force in its new night fighters. Lastly, he was tasked to report on the effectiveness of the V-1 buzz bomb attacks against British cities. Chapman fed false information to Germany that reduced the effectiveness of the V-1 and, later, the V-2 rocket attacks.

On June 29, 1944, Chapman was dropped by a German plane over England near the town of Cambridge. As in his first landing, he met with the local police who then made contact with London. Chapman told his handlers about his new mission, and an elaborate disinformation campaign was launched to fool the men in Berlin.

By now, Agent Zigzag was growing irritable and tense. He wanted to go back to Paris and continue his undercover operations. That request was vetoed by MI-5, and it was decided after much heated debate that Chapman’s role as a double agent should end. In November 1944, Agent Zigzag was informed that his services were no longer needed by the British government. Eddie left with 6,000 pounds in cash from the British along with 1,000 pounds that remained from the money given to him by the Abwehr. When Graumann failed to hear from Chapman after several long months of waiting, he believed that his prize agent had been either killed or captured.

Back to His Old Ways

After the war ended, Chapman returned to his career in crime. He dabbled in black market activities and the protection rackets in London, rejoining his old friends from years before. He and Betty had a daughter named Suzanne, born in October 1954. He illegally transported gold across the Mediterranean and bought a share in a ship called the Flamingo, which was used for illegal activities. In the 1960s, the family moved to South Africa.

In 1966, Eddie wrote his memoirs, The Real Eddie Chapman Story, leaving out much of the juicy material that would become public much later. His life story was made into a movie called Triple Cross starring Christopher Plummer. Agent Zigzag died in December 1997, at the age of 83, closing the book on a unique espionage story of World War II.

Peter Kross is the author of Spies Traitors and Moles and The Encyclopedia of World War 2 Spies. His new book,Target Fidel, is scheduled for publication this year.

Do you have any info on Eddie Chapman’s time in South Africa please