By Sherri Kimmel

I am riding a borrowed bike along the Rhine, passing the Schaum-Hof, where last night I dined on a deck overlooking the river with a stately Dutch lady friend of a friend. She lent me this bike and directed me to this path.

Coming fast on my right is the Eva Braun House, a brown brick, turreted three-story rising benignly among large, leafy trees. It was here, behind a brick wall enclosure, festooned now with the red, white, and pink blooms of early summer, that Hitler spent many a sweet weekend. I pass the Dreesen Hotel, its flat-fronted white expanse slung out like a docked Mississippi riverboat against the bike path. Its sleeping room balconies jutting over the path, the Dreesen peers over the Rhine, as it did when Adolf Hitler and Eva, his mistress, repaired here for their evening meal.

Where I am headed is 40 minutes away by bike, along this ribbon tracing the Rhine, then I cross over a busy highway. I stop to fill a paper bag, a treat for the man who awaits, the man who once was connected to Hitler, not by allegiance but by status in the foreign service for the dictator’s Reich.

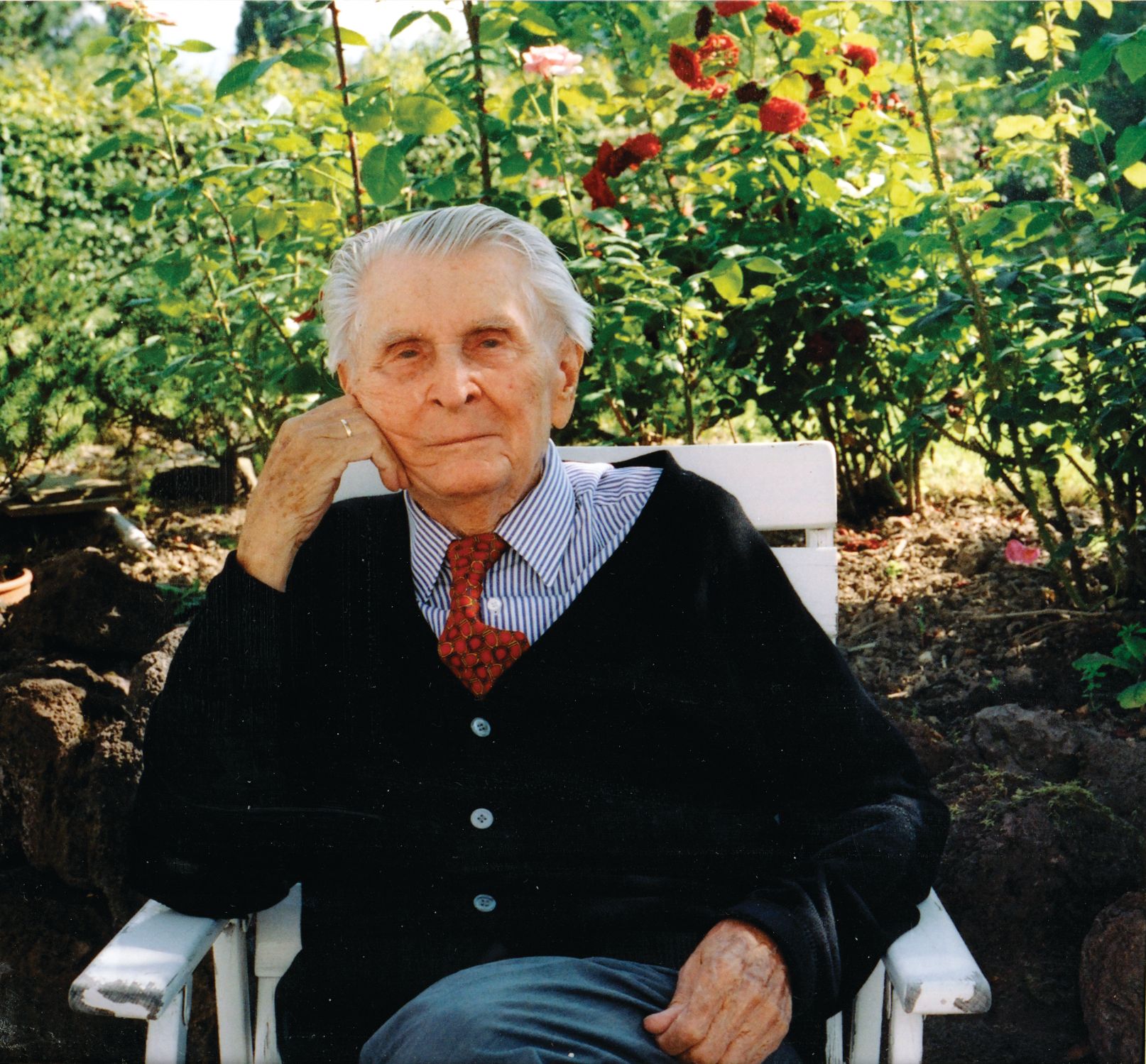

I first met Erwin Wickert in June 2001. I had taken the short train hop from Cologne to Oberwinter to write a biographical sketch for the alumni magazine of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Wickert attended the college in the mid-1930s. I found his face attractive with aristocratic cheekbones and Prussian blue eyes. His smoothly backswept white hair suggested a dashing youth and fastidious old age. Though his face preserved his beauty and dignity, his frail and bent frame reminded me just how long he had been on this Earth.

Long enough to witness pre-Hitler privation in his native Prussia, long enough to have joined the Nazi party though he could not tolerate the National Socialists, long enough to staff, in a minor capacity, one of the most important Axis embassies of World War II. He had witnessed the destruction and rebirth of Germany and participated in that rebirth as a civil servant for the architect of the new Germany, Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.

Named Time magazine man of the year in 1953, and in 2003 voted by Germans in a television poll the most prominent German in history (Martin Luther was fourth and Hitler nowhere to be found), Adenauer was Wickert’s family friend and political mentor. Wickert, once described by a journalist as “an exceptional person in foreign service,” spent most of his life close to the main stage but never was a major player on it.

The day we met, we sipped tea from a silver pot at a lace-covered table in a back garden that was fragranced by 100 rose bushes. He spoke of working for an enemy of the United States while living in the land of America’s other great foe, Japan. His encounters with evil in Tokyo in the 1940s fascinated me. But for a straight biographical sketch I needed to learn about his career as an award-winning radio-play writer and commentator and his eventual return to the foreign service as the German ambassador to Romania.

It was a career that he began as the lowest functionary in the German embassy in Shanghai and concluded when he returned triumphantly to China in 1976 as the German ambassador. And then there was his other vocation as author of more than 20 books of fiction and nonfiction. At age 90 he continued to publish, regularly bylining broadsheet-length newspaper articles about current politics and historical events he has witnessed as well as book reviews. In the fall of 2001, he published the second volume of his autobiography, and a book of his collected journalism came out in spring 2003.

His most recent book, correspondence to and from famous friends including the philosopher Karl Jaspers, author Günter Grass, and former chancellor Kurt Kiesinger, was published in January 2005. After all the drama he has lived through he resides quietly alone (his wife died a few years earlier) in a sweeping house perched on a hill overlooking the Rhine.

My focus during that first visit was his arrival at Dickinson College, a ploy to escape the repression he had endured while living in a country wild for National Socialism. There was no one more Hitler happy than his own father, also named Erwin, a minor government functionary. During our six hours together that day, Wickert and I skimmed the highlights of his life as a young child in Brandenberg in those days of endless bread lines and wheelbarrows full of useless currency.

I learned how his father had forced his freethinking 18-year-old son to offer himself as an SS officer candidate. This was in 1934, one year after Hitler had gained power. The son had sabotaged his appointment, though, when, during an interview, his Nazi interrogator asked why he was applying. “It is my father who wants me to become an officer,” he replied.

The elder Erwin wrote the regimental commander demanding to know why his son had been rejected, but no reply came. And the son never revealed what he had told the SS man. After spending one required semester in a well-appointed SS comradeship house for students attending Karl-Wilhelm University in Berlin, Wickert headed to America to escape the authoritarian demands of his country and his father. He formalized his rejection of his father and his beliefs by refusing the elder Wickert’s offer to help pay his way.

By the time Wickert reached Dickinson, where he learned “democratic ideas,” as his father later griped to a neighbor, he had already made something of a name for himself in Germany as a writer. In America he continued his journalism, editing a magazine for foreign exchange students and earning his degree in economics at Dickinson.

Intrigued by the Far East, he hopped trains with hobos, hitchhiked cross-country to San Francisco, and signed on as a deckhand on a ship bound for China. Wickert spent several months in China traveling, polishing his writing, and meeting future legendary figures such as John Rabe, known today as the “Oscar Schindler of China” for his role in saving 250,000 Chinese.

Penniless and ill in China, Wickert returned to Germany, where he pursued a Ph.D. in art history at Heidelberg University. There he convinced the philosopher Karl Jaspers to admit him to his select seminar. Wickert’s burgeoning publishing career and his stint in America had made him attractive to this pioneer of existentialism. After earning a Ph.D., Wickert hoped to escape Germany again and return to America as a cultural attaché. While awaiting his assignment from the German foreign office, he was offered an assistant professorship at Heidelberg. He did not stay long because all the men on campus were being drafted into the military.

“I wouldn’t survive the war as an assistant professor in Heidelberg,” he told me. “Somebody would grasp me and say, ‘You’re a young man; what are you doing there at the university teaching history of art? You have much better things to do—you go to the army, shoot people,’ or something like that.” When he shared his concerns with Jaspers, the philosopher told him, “The foreign office has many people who have been abroad like you and have been in America. You’ll find people who understand your ideas much better than people who are in the army.”

Wickert called the foreign office again and eventually was posted to Shanghai. He quickly married his Heidelberg girlfriend and, lacking any allegiance, bowed to foreign office pressure to join the Nazi party. Wickert knew that if he did not acquiesce they would be stuck in Germany. Erwin and Inge, nicknamed Franz, climbed aboard a train to Moscow then took the Trans-Siberian Railway express across the continent to China, snacking on the caviar that was offered freely in the passenger cars. It was August 1940.

Assigned to the German embassy in China’s most important commercial center, Shanghai, as the youngest and lowest-ranking employee and a radio attaché not a diplomat, Wickert soon fell out of favor with the Nazi brass. His job was to program a German station, one of 26 radio stations in the city. He naively proclaimed it “the voice of Europe” and refused an order to play only German classical music, bumping Wagner for the American jazz records he had acquired while studying at Dickinson.

When some Italian fascists approached him about broadcasting a program on the station, he showed them the door. Patience with his impertinence ended on the eighth anniversary of Hitler’s rise to power, January 30, 1941, when Wickert objected to a radio speech that the Nazi party chief gave to mark the occasion.

“That was underestimating the power of the Nazi party, because the next day, he [the party leader] sent a telegram to the German ambassador and to the foreign office to have me recalled immediately,” Wickert told me. “He said I was very tactless, very young, and unreliable. I had really made a blunder in making a Nazi chief my enemy. But I don’t regret it,” he said with a satisfied smile. “I feel hate for him.”

Wickert rallied high-ranking supporters to preempt his return to Germany. Erich Kordt, the second-ranking German minister in Tokyo, pulled some strings and had him transferred to the embassy in Japan. Returning to Germany, Wickert said, would have meant his death.

In Tokyo, Wickert was the second lowest in rank and still not of diplomatic status. His tactical blunders in Shanghai made that impossible. For the embassy staff Wickert was entrusted with writing a daily bulletin of news that he culled from American and British stations through two listeners who reported to him. Along with his four-page news digest, the embassy published another bulletin of “official news” or propaganda.

In his radio programming, Wickert presented Allied reports along with the German and Japanese points of view. While his mornings were occupied dictating his bulletin to a secretary, he spent the afternoons reporting to Berlin the Japanese news “that drew our attention. We talked politics all the time in the afternoon. I was busy all the time. The times were so fascinating and full of surprises.”

Now, a year after my first visit, I am ready for surprises. I see his house ahead—white stucco with a sturdy wooden door. Wickert is waiting beside the open door, even smaller and frailer than I remember, but just as neatly attired in a crisp pinstriped shirt, red tie, navy sweater, and gray slacks. He kisses me on both cheeks, then we head downstairs to his writing studio. Shelves hold various editions of his books and yellow binders containing clippings of all the articles he has written since the early 1930s. The binders, with labels inscribed in his neat hand, are arranged chronologically and by subject.

I sink into a leather chair and pour a cup of tea from the pot that his white-aproned maid has whisked into the room. He gets right to the point, matter-of-factly and succinctly laying out the parameters of our talk. I may interview him from 9 am until 1 pm each day. He takes a nap each afternoon to rejuvenate himself for his research and writing. Evenings he reserves for correspondence. It is clear by his tone and demeanor that the terms are not negotiable.

I am eager to explore Wickert’s encounters with Richard Sorge, the German-born spy for Stalin who has been romanticized or vilified—depending upon the author’s or director’s point of view—in prose and film. Sorge is now championed as a hero in Russia, the country that played the Judas role after his capture by the Japanese. Stalin did not try to stop his death by hanging in 1944 in Tokyo.

Sorge and Wickert met in 1936, when Wickert was visiting China for the first time after his graduation from Dickinson College. Wickert, who wanted to write articles about the living conditions of Chinese and Japanese workers, had been referred to as “a man from the Frankfurter Zeitung.” Sorge was considered an expert on labor, a fitting concern for a closet communist. While working publicly as a journalist, Sorge went about his espionage. In 1941, Wickert was back in China, now with the embassy in Shanghai, and Sorge was still plying his public career as a writer and his secret one as a spy.

“The books made a big deal about how handsome and dashing he was. Was that true?” I asked.

“No, he wasn’t handsome,” Wickert replies, and I feel mildly disappointed. “He was tall, and maybe for girls he may have been good-looking, but his walk … he threw a little bit his leg behind him. I think he must have been hurt.”

“Yes, in World War I, with shrapnel.”

Wickert described Sorge’s face. “Something about it didn’t quite fit together, and so everybody looked twice when they saw him—an interesting face….”

By the time Wickert moved to Tokyo’s German embassy, Sorge had shifted his spy cell from China as well. He made fast friends with Wickert’s boss, Ambassador Eugen Ott, and his wife, Helma, enabling him to infiltrate the embassy. Sorge began publishing a news bulletin for the German community that he composed in an embassy office, and he and the ambassador had breakfast together almost daily. Wickert laughs off Weymant’s claims that the 40-ish Helma and Sorge carried on a torrid affair. Sorge, he says, went for less “massive” and younger women.

One of the younger women to whom Sorge took a shine was Wickert’s young blonde bride, Franz. Wickert broke up their flirtation at a party.

The legendary drinking, he says, was not exaggerated. Wickert recalls how, one hot summer night when Franz was staying in the mountain resort of Karuizawa, he visited Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel bar. There sat Sorge, drunk and loudly denouncing Hitler as a criminal for attacking the Soviet Union. Germany had invaded Russia that very day.

Wickert remembered: “I said, ‘Sorge, keep quiet. There are all sorts of people here, maybe even the agent of the German secret police, Meisinger, or his people. He said, ‘Meisinger is an….’ I had never seen him drunk like that.”

When Sorge attempted to leave the hotel, Wickert stopped him, saying firmly, “You can’t go out like that. I’ll order a room for you in the hotel, and you’ll stay there.”

He continued, “So I got a room for Sorge, got him to the room and then I put him to bed and went out. The next morning, he came out unshaven. He found me in the breakfast room and asked, ‘Could you lend me 100 yen?’ I said, ‘All right.’ I thought I would never see them again, but he paid them to me.”

Did Wickert suspect Sorge?

“He was one of these more adventurous people who was disgusted with everything in the world and was sarcastic about it. But we never thought that in the background he had this very strange belief—strange, for an intelligent person, about socialism.”

On day two of the interview, I am eager for more encounters with evil, though in Sorge’s case one might argue that he was not evil—just committed to an unpopular cause. But there is no doubt about the Butcher of Warsaw, Josef Meisinger.

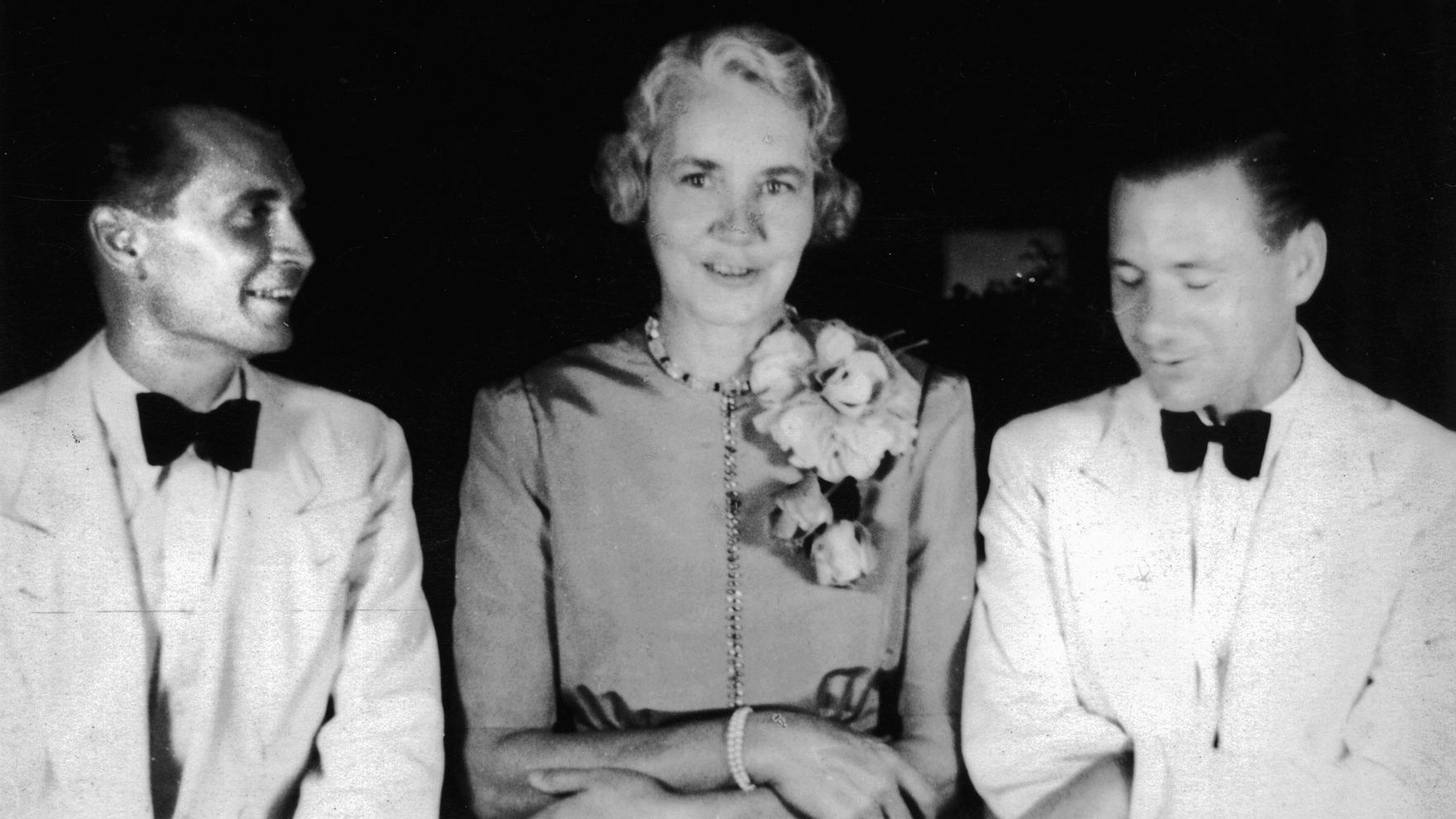

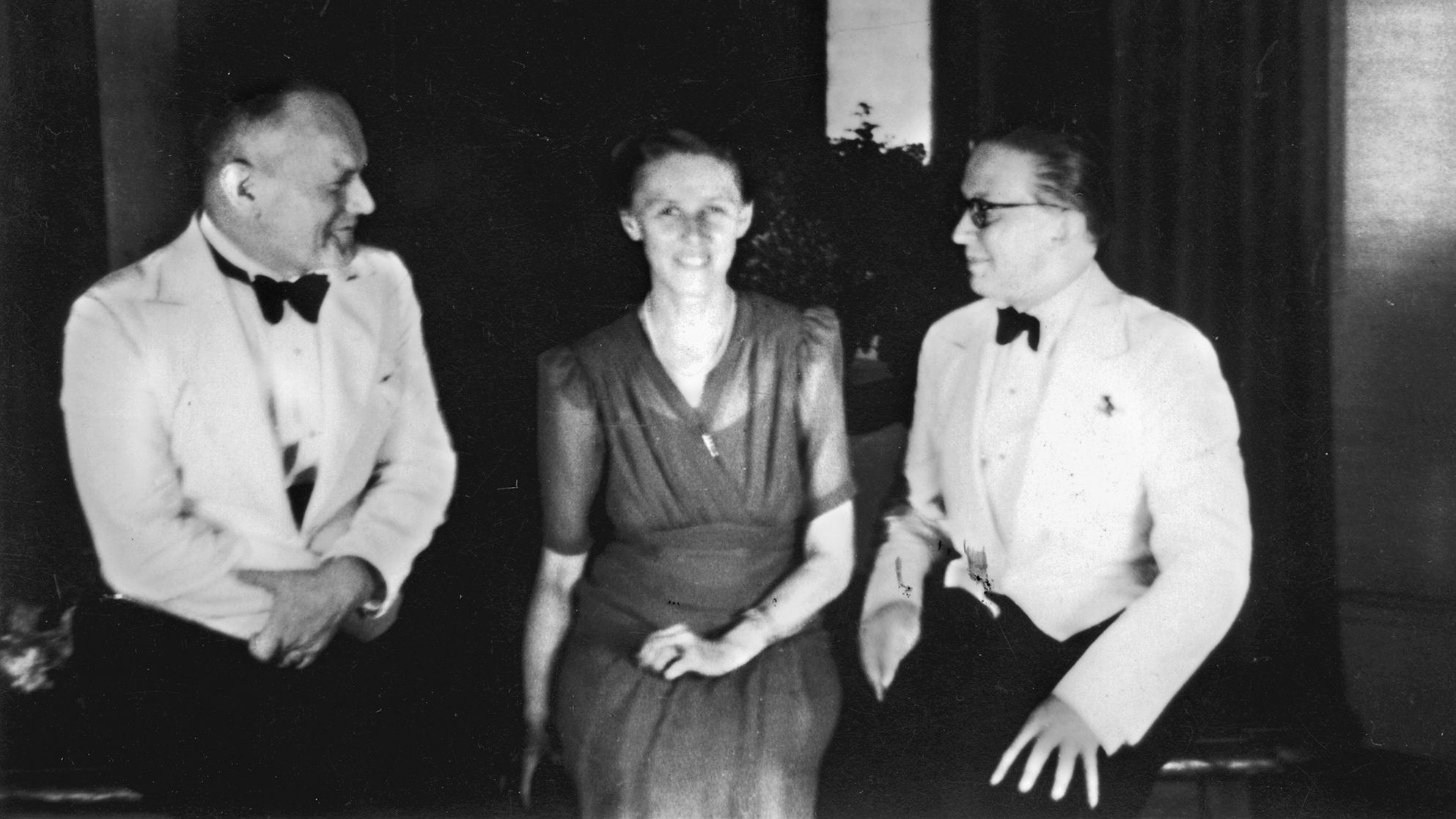

Wickert takes me into a second downstairs office, where he keeps his old files. He begins plowing through a box of photos, meticulously categorized by his late wife. He pulls out photos of an embassy party, the women in fancy dresses with their 1940s rolled hair. Wickert, in white tuxedo and black bow tie, laughs with the towering Helma Ott. There is Ambassador Ott with Erich Kordt, Helma Ott with the philosopher Count Karlfried Graf Dürkheim, then Ott’s son Helmut with a cluster of Teutonic beauties. He shows me a photo from another day, with Shinzaku Hogen, his close friend, a future Japanese ambassador, at his left. And then he shows me Meisinger, stocky, brutish, coarse.

The arrival of Meisinger in Japan was fear inspiring because of his penchant for murder. According to Wickert, his slaughter of Polish intellectuals and Jews was considered even too much for Heinrich Himmler, Hitler’s SS chief. When Meisinger came on as the head of the embassy’s SS, Wickert began having murderous fantasies of his own.

Wickert had his reasons. “I was not very well liked by him because of my fight with the Nazi leader in Shanghai. There was always the danger that if you really antagonized Meisinger he would say, ‘Well, this young man, Wickert, might be better to go to the front in Germany. We’ll put him on one of the blockade runners.’ And the blockade runners were mostly sunk, intercepted by enemy warships or by planes.”

Wickert and his friend, the young diplomat Franzl Krapf, mulled over various assassination plots. “Whenever I was awake during the night I thought about the most adventurous things or methods which seemed, in the daytime, absolutely impossible,” Wickert says with a tone of resignation. “The police and Meisinger’s friends in the Kempetai (Japanese secret police) would have found me out, and that would have been my end.”

Meisinger was eventually returned to Warsaw to stand trial for the murders. “It served him right that he was hung,” says Wickert, with a nod of satisfaction. “For a long time after he was dead the thought tormented me, whether I had overlooked the possibility to kill him.”

Wickert first encountered Japanese Emperor Hirohito on New Year’s Eve at the palace in Tokyo. Russian and German embassy staff were invited to a reception with Hirohito and the royal family. “We were presented one by one to the emperor and empress, and on both sides were the princes and princesses, all in robes like the pre-First World War. You went in, and you were called up in the anteroom. They said, ‘Mr. Wickert,’ and the door opened, and you had to go in, slowly, walk to the midst of the balustrade. You had to bow to the emperor. Then you had to go two or three paces to the right, to the empress, and then to the princes and princesses.

“On the way back, you had to go backwards to the door. You should always look at the balustrade. It was difficult to find the door without looking at it. In the midst of going back you had to bow again. I was so nervous. Why? Because in front of me was a lady from the embassy, a diplomat’s wife. When the door opened, she had to bow, too. What you call it?”

“Curtsy,” I prompt him.

“Curtsy, yes, and then her whole dress opened up, because it was very tight, and so I thought this was very funny. It didn’t fall apart completely, but it was close to doing it.”

On November 30, 1942, Wickert was aboard the German auxiliary cruiser Thor, a commerce raider that was docked in Tokyo Bay. As he toured the vessel, a sudden explosion ripped through the neighboring supply ship Uckermark. Thor was sunk by the explosion, and Wickert swam for his life.

“I heard some sort of a hiss,” he remembered. “Suddenly there was a cloud on the right side of me, several hundred meters high and with flames coming out… I went to the railing, too, and jumped. I went down very deep first. I was trying to swim to land in Yokohama Harbor. Doing the backstroke, I looked up and saw the cloud, the whole cloud, and parts of the ship. I looked back to the ship and saw the people who were standing there still…. They didn’t know what to do. I thought I would die there. This German was on his balcony looking at what happened in the harbor—all flames and smoke and clouds. He saw me coming, and he said he thought he saw a ghost. My face was green, and I had a cut because the debris was flying around.”

That night, Wickert joined his wife at Kawaguchi, the resort in the shadow of Mount Fuji where the embassy families lived. The next day, his second child, Ulrich, now a broadcaster in Germany, was born.

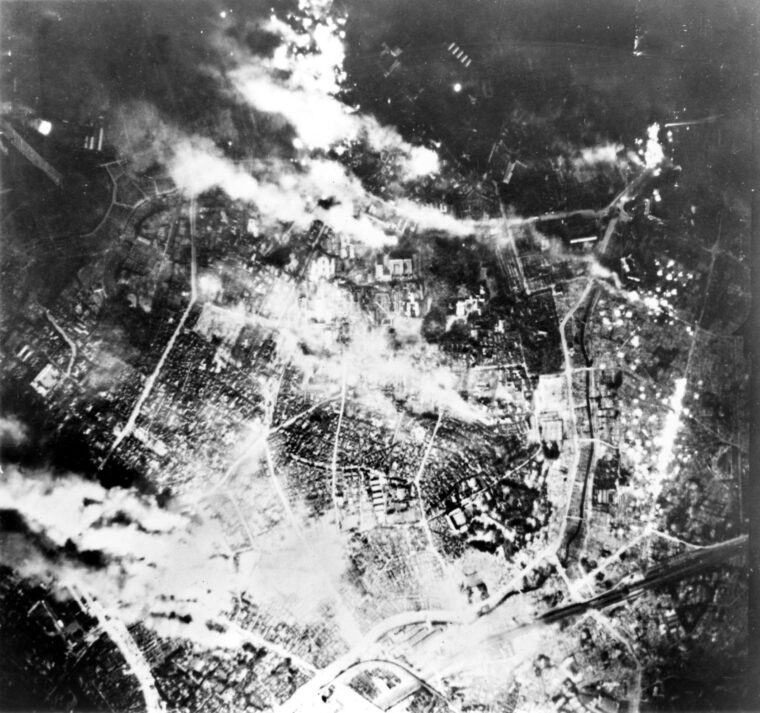

During the last nine months of the war, the Americans began what Wickert called “incendiary bombing.” Large areas of Tokyo burned, lighting up the night sky, leaving nothing but safes containing family treasures poking above ground. He experienced his last big air raid on May 25, 1945, after Germany had capitulated but Japan was still at war. He remembered that when a plane fell the Japanese “applauded but didn’t know if it was an American plane or a Japanese plane.” That day, while his wife and children were at their Kawaguchi home, Wickert escaped their other flame-engulfed house in Tokyo.

“Everything burned, went down. And just a few yards away from our so-called air raid shelter there was a man dying. He was hit by a bomb in his leg, and the leg was very swollen, and the trousers were very tight about it,” Wickert recalled. “So I went to the air raid shelter where we had our first-aid equipment. There was a scissor, and I tried to cut the trousers, and then he cried. He said it was hurting so much. He had what do you call … Rosenkranz.… He had a Buddhist rosary.”

Wickert approached a policeman. “I said, ‘We have somebody who is hit, and if you don’t do something about it, he’ll die. Could you help us to carry him to the hospital? The hospital was burned down, too. So we just had to let him die. In the morning he was dead already.”

When the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Wickert was safe with his family at the Mount Fuji resort. He understands the reasons for the actions by the Americans.

“I thought, yes, because the war couldn’t go on, and the other possibility would be Americans landing in Japan. Invasion. And I knew how the Japanese felt about it. They would have sacrificed, like the kamikazes. And that would have prolonged the war without any reason. The end would be the same. The Americans would come, and I thought maybe they would have dozens of bombs, atomic bombs. Then came the Nagasaki bomb, so I thought it was very good to have it, to end the war right now as soon as possible. So I think it was the right thing.

“On the other hand,” he continues, “I’m not sure whether the Japanese would have really sacrificed themselves in defending their country if the landing operation would have gone on a long time. There was the discrepancy between the corruption of the people—uninterested in the war and everything at home—and the cries of the young officers to continue to fight, to sacrifice themselves. When I went to Tokyo immediately after the capitulation I saw the banners in the streets, and I wrote them down: ‘Welcome the American victories over all the world.’“

He shakes his head. “Even now I cannot understand it. Everything was broken down; the myth was broken down. Japan was not able to be the nation really sought out by the gods, by heaven, to pacify and to reign.“

It had taken a while for the news of Hitler’s April 30, 1945, suicide to reach the Germans in Tokyo, for Berlin sent no announcement to the embassy. Finally, someone intercepted a German news broadcast—proclaiming that Hitler had died—from a radio station in Norway. Heinrich Stahmer, who had taken over for Eugen Ott as ambassador, called for the embassy staff to attend a memorial service for the fallen Führer.

“All the German embassy personnel came,” Wickert remembered. “There was a symphony orchestra, which was directed by the German Helmut Fellmer. They played Siegfried’s Death or something else from Richard Wagner. And he [Stahmer] gave a speech that Hitler died a heroic death. And then he had the colors of the party thrown out, and the national hymn was thrown out, and there also was a program.

“I said, ‘I’ll preserve this mimeographed thing.’ I still have it, and I published it in this book.”

Wickert held a copy of his 1991 autobiography, Mut und Übermut (Courage and Insolence). “I think it was the only memorial service anywhere held for Hitler. In Germany, certainly not.”

Wickert was relieved that Hitler was dead. “[I was] suddenly elated. Like a pressure had gone from me. Like, for instance, you have a toothache or backache. You get used to it. Maybe for years you have a backache. But then suddenly you are free of any complaint. It was a quiet elation, a freeing.”

Soon after the memorial service came confirmation of news that Wickert had reported in 1944 about Jews being killed in Nazi concentration camps. The first word of the atrocities had come from British and American broadcasts. Wickert was ordered by Ambassador Stahmer to retract his reports.

“My impression had been that the army was still very intact, not doing any atrocities,” Wickert said. “When I left Germany in 1940 there was still the old German officers’ morality. And then this happened. It was absolutely impossible for me to understand it. At first I didn’t believe it.”

With Hitler gone, the embassy staff rebelled at taking orders from his yes-man, the grieving Stahmer. “We wrote him a letter and said, ‘We don’t take any orders from you anymore. You have failed in every way.’ This is the letter we sent him,” he said, turning to a page in his autobiography.

The embassy in shambles, Wickert retreated to the area around Mount Fuji, where he spent the next two years with his wife and two sons reading philosophy and American newspapers while writing two novels and two novellas. Finally, he was writing again, a pleasure he had denied himself during the war because he thought it would be unseemly to write love stories while people were dying all around him. He supported his family with installment payments from a war insurance policy he had taken out in Tokyo and by trading their valuables on the black market.

“It was two years of leave in the midst of life to study, work, do whatever you wanted to do. It was wonderful,” he smiled.

The Wickerts’ reverie ended in October 1947 when they returned to Germany on a troop carrier. While his wife and children stayed with his parents, Erwin was detained in a camp in southern Germany. By deceiving the American officer in charge of the camp, Wickert was able to gain early release.

“I outsmarted and betrayed them. I mean, I was a liar,” he said in a tone of voice which conveys that he was not proud of the fact.

Joining his wife and children in Heidelberg, Wickert began to piece together a living by writing radio plays. But his career was briefly halted when he was asked to prove he had been legitimately de-Nazified.

“I showed them the letter of the party leader in Shanghai who asked for my recall, saying I was a terrible character—no tact and no cooperation. And I had a letter where they told me that my book was forbidden [in Germany]. And they said, ‘You’ll be de-Nazified all right.’ From then on I was an established radio writer.”

Wickert built a lucrative career as an award-winning script writer and broadcaster before rejoining the foreign service in 1955, serving in Paris, Bonn, and London before being named ambassador to Romania in 1971. He returned to his career as a writer after retiring as ambassador to China, where he observed the post-Mao opening of the country between 1976 and 1980.

One issue that Wickert had been reluctant to discuss was his relationship with his father, who was a devoted Nazi. Finally, he was willing to comment on the subject two weeks after the death of his sister.

“Of course it would have been … I would have preferred, I mean, if I had a father who in any way respected my ideas,” he responded when asked whether he had hoped to reconcile with his father. “But … I saw it was impossible.”

Wickert cleared his throat and then explained in a halting and sad voice that, though his father lived until age 92, he was an unrepentant follower of Hitler.

“He held to his beliefs—very stubborn. I mean, he was an unfortunate character, “ he remarked. “I didn’t hate him. I saw him shortly before he died, and I talked with him but knew he wouldn’t understand me anymore. He wouldn’t understand anything at all because he was more or less in a coma. But I pitied him because of his way of leading his life. That’s it.”

During a life of adventure and intrigue, Erwin Wickert somehow managed to remain an intensely private person. He was willing to share glimpses of the past; however, he set solid boundaries and much of what he remembers will remain only with him. He passed away on March 26, 2008.

Sherri Kimmel is the senior editor of Dickinson Magazine and director of editorial services at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and lives in nearby Mechanicsburg. Kimmel won a research grant from Dickinson College in 2002, which funded two trips to Germany to interview Erwin Wickert.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments