By Allyn Vannoy

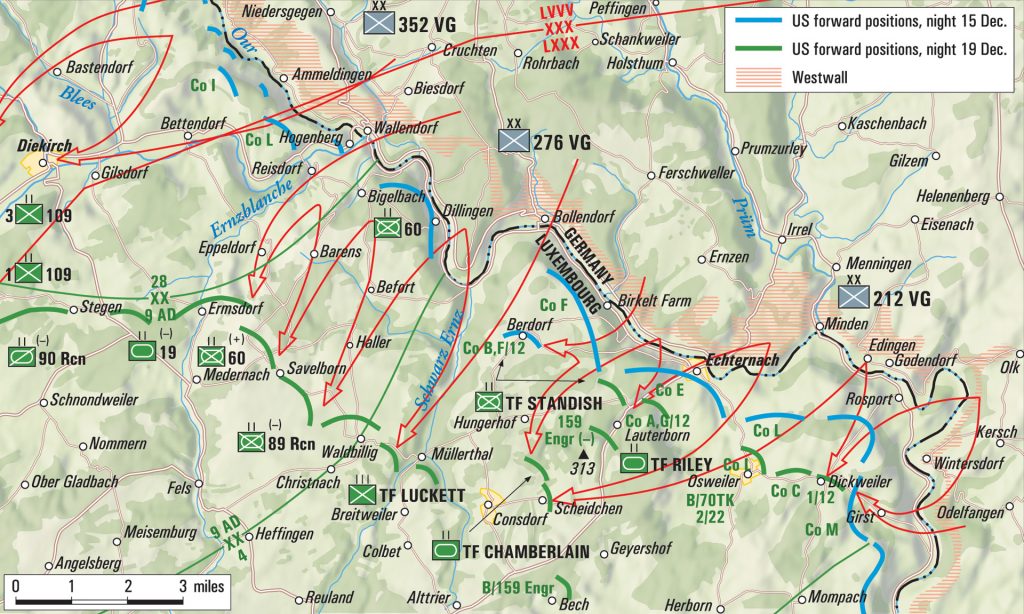

Army commanders understand that the key to dealing with an enemy breakthrough is to slow the enemy’s advance and prevent the breach from widening—that is, “holding the shoulders.” During defensive operations by Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’s U.S. First Army in the Ardennes, a series of actions took place on the southern shoulder that was important to the final outcome of the battle.

On December 16, 1944, General der Panzertruppe Erich Brandenberger’s German Seventh Army, the southernmost of the four German armies spread across the Ardennes, launched its divisions across the Our and Sauer Rivers.

Americans units in position to meet the attack included elements of the U.S. VIII Corps—the 4th Infantry Division’s 12th Infantry Regiment, the 109th Infantry Regiment of the 28th Division, and the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion of Combat Command A (CCA), 9th Armored Division.

The 109th Infantry was struck by elements of the German LXXXV Corps’ 5th Fallshirmjäger (Parachute) Division and 352th Volksgrenadier Division (VGD); the 12th Infantry was assaulted by the 320th and 423rd Regiments of the 212th Volksgrenadier Division, commanded by Generalleutant Franz Sensfuss; and the 60th Armored Infantry was attacked by the 276th Volksgrenadier Division, under Generalmajor Kurt Möhring.

The latter two volksgrenadier divisions constituted the LXXX Corps under General Franz Beyer. Beyer’s grenadiers were reinforced by the attachment of the 408th Volksartillery Corps, 1095th Artillery Battery, and the 657th Heavy Antitank Battalion.

The Sauer River drains southeastward to the German frontier, where it absorbs the Our River and forms the Luxembourg-German border until it joins the Moselle northeast of Luxembourg City.

The LXXX Korps was to cross the Sauer south of the confluence with the Our at the town of Wallendorf, the river winding and steep-banked, fast-moving as it was swollen by rain and snow—a challenge for assault forces as well as bridging engineers.

They faced American artillery batteries on the heights southwest of Beaufort and Echternach. Field Marshal Walther Model, commander of Army Group B, stressed to General Brandenberger the need to destroy or displace the American artillery.

Complicating the situation was the deep Schwarz Ernst gorge (referred to by some sources as the gorge of the Ernz Noire), extending south from the Sauer, splitting LXXX Corps’ frontage. General Beyer feared that it would provide an avenue for an American counterattack, but failed to recognize that his own troops might make use of it.

Prior to being transferred to the Ardennes, the U.S. 4th and 28th Infantry Divisions had been mauled during fighting in the Hürtgen Forest. The 4th was commanded by Major General Raymond O. (“Tubby)” Barton, a West Point graduate and World War I veteran.

The 4th’s regiments were under-strength by an average of 500–600 men; many rifle companies were no better than half-strength. Equipment was in short supply, worn out, or in poor condition.

Each of the division’s 105mm howitzer battalions was placed in direct support of a regiment. General support was provided by the 155mm howitzers of the division’s 20th Field Artillery Battalion along with two battalions attached from the 422nd Field Artillery Group—the 81st and the 174th Field Artillery Battalions. On December 16, the 70th Tank Battalion, attached to the 4th Division, had only 11 operational Sherman tanks.

The 12th Infantry, spread along the Sauer River—veterans of the D-Day landings on Utah Beach and commanded by Colonel Robert H. Chance—found itself with limited radio communications due to the rugged terrain. A static linear defense here was out of the question because of the length of the front and the meandering course of the waterways that cut through the hills.

General Barton instructed his regimental commanders to maintain only small forces at river outposts, holding their main strength in separate companies at nearby villages. This also allowed troops a respite from the harsh winter weather. One regiment had only five companies on the line, situated in villages along main and secondary roads leading from the Sauer.

The problems of control and coordination were made more difficult by the wide dispersion of units and their isolation in wooded areas separated by gorges and crevasses. Critical points in the 12th Regiment’s defense included Berdorf (held by F Company), Echternach (E Company), Lauterborn (G Company), Osweiler (L Company), and Dickweiler (I Company)—units of the 2nd Battalion, under Major John W. Gorn, and 3rd Battalion, commanded by Major Herman R. Rice.

The 60th Armored Infantry Battalion, 9th Armored Division, under Lt. Col. Kenneth W. Collins, held positions on a high plateau between the Sauer in the north and the Schwarz Ernst gorge to the south—the gorge lying 300–500 feet below the surrounding tableland, in some places with sheer cliff walls.

The gorge did not strengthen the armored-infantrymen’s positions, as three roads cut across it. One led to the rear of American positions at Beaufort, where Colonel Collins had his headquarters in a 12th-century castle. Further up the gorge, the other two roads led west toward positions of the 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion.

The 12th Infantry covered the northern entrance to the gorge, but the regiment was overextended and had only a small outpost to block movement up the gorge.

Collins was also concerned about his northern flank, as more than a mile separated his positions from those of L Company, 109th Infantry. To cover the gap, he had only a squad at the village of Hogenberg, looking down on the town of Wallendorf and the juncture of the Our and the Sauer. Collin’s main positions were located atop steep bluffs with good fields of fire into the valley of the Sauer.

The Seventh Army was the weakest of the German armies of the winter offensive. Its 276th VGD was a short-lived unit—destroyed in the Falaise Pocket in August and then re-organized in Poland as a volksgrenadier division (VGD).

Brandenberger believed the 212th VGD was the Seventh Army’s best unit, but he withheld its 316th Regiment as part of his army’s reserve. A veteran of three years of fighting on the Eastern Front, the 212th Infantry Division had been shattered during the retreat from Lithuania in 1944, then sent to Poland in September 1944 for overhauling before becoming the 212th VGD.

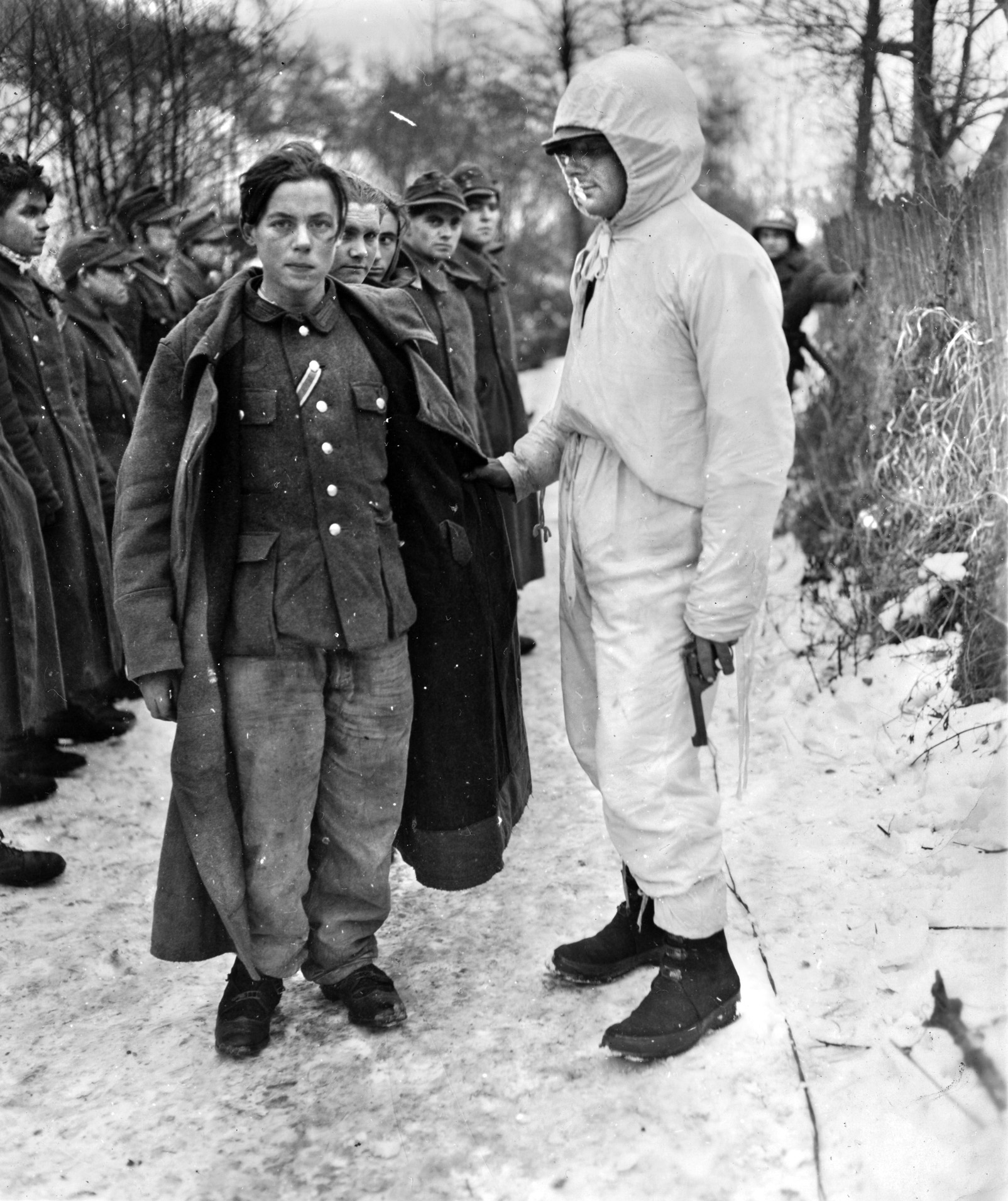

Its replacements were better than average, although there were many 17-year-olds among them. Unit commanders and non-coms were experienced, and morale was high. Although at full strength, it was short of communication equipment and had only four assault guns as armor support.

The LXXX Corps initially had no armored support except for four or five sturmgeschütze (assault guns) in General Sensfuss’ division. Möhring’s division also had four, but they were not available until December 19. The supporting 408 Volksartillery Corps lacked its sixth battalion with its 17cm guns and 21cm mortars.

The 212th VGD was ordered to attack over the Sauer on either side of the town of Echternach; contain American troops by a thrust towards Junglinster; eliminate American artillery in the Alttrier-Herborn-Mompach area; and reach and hold along the Schlammbach, about seven miles northeast of Luxembourg City. Once this was accomplished, the division was to assume a defensive posture to protect the southern flank of the German offensive.

On the night of December 13/14, in preparation for the offensive, the 212th’s 423rd Regiment made a forced march from Trier, and by the next day it had reached the right wing of the division. The following night all three of the division’s regiments assembled behind a single battalion acting as a screening force along the Sauer between Bollendorf and Ralingen.

The 423rd was north of Echternach, the 320th Regiment was on the left—where the Sauer turned east of Echternach—and the 316th was the Seventh Army reserve. The leading assault companies began crossing the Sauer at dawn on the 16th, but they were hindered by the swift current and their shortage of rubber boats.

The attack began inauspiciously as German engineers were forced to abandon their efforts to place a bridge at Wallendorf by American artillery fire and had to restart operations later at Bollendorf. Heavy fog also hampered progress of the assault companies, although it concealed their movements and allowed them to cut off several American pickets and then make a quick occupation of Bigelbach.

The immediate objectives of the 423rd Regiment were to seize the plateau in the area of Berdorf, cut the road running west from Lauterborn and Echternach, and then link up with the 320th Regiment.

It was originally intended that the 320th should cross the Sauer at Echternach, which lay in the center of the 212th VGD’s lines, its first objective being a series of hills north of the villages of Dickweiler and Osweiler. Once in possession of these hills, the 320th was to seize the two villages, then advance to join the 423rd. But this plan had to be adjusted because the river was swollen by rain and snow and too fast-flowing for the rubber assault boats.

The 1st Battalion, 423rd Volksgrenadier, on the regiment’s right flank, headed towards Berdorf, while the 2nd Battalion, on the left, moved towards Lauterborn. Beyond these villages lay Consdorf and Scheidgen, headquarters of 12th Infantry’s 2nd Battalion, under Major Dorn, and artillery positions at Alttrier.

One company of the 1st Battalion, 423rd Regiment, overran three outposts, capturing mortars, machine guns, and antitank guns while cutting the Echternach-Luxembourg road. A German assault struck E Company in Echternach at about 11 am. Though surprised, many of the outpost’s troops worked their way back to a hat factory on the southwestern edge of the town, where they organized a strongpoint.

By 11:30, elements of G Company, near Echternach, were surrounded by the 1st Battalion, but continued fighting at a mill near the village, while a platoon of I Company held on in buildings at the west edge of Lauterborn.

The LXXX Corps’ assault began to falter as orders to bypass pockets of resistance were partially ignored and troops became involved in costly and time-consuming fighting for insignificant villages, keeping the volksgrenadiers from reaching their main objectives.

The German infiltration did considerable damage to the 12th Infantry’s F Company outposts. Three were located northwest of Echternach near the village of Berdorf, on high ground above the Sauer, and in farm buildings, all held in platoon strength.

A fourth OP, manned by an understrength squad, was in the Schwarz Ernst gorge near the point where a road led across the gorge west to Beaufort. All four outposts were captured, their personnel either killed or taken prisoner, except for two men at the Schwarz Ernst OP and 13 who had been on patrol.

By late morning, the volksgrenadiers had driven a platoon of F Company to the shelter of a stone farmhouse at Birkelt Farm, close to the river a mile and a half east of Berdorf. The outpost was able to avoid being overrun, and the platoon of 21 infantrymen and two artillery observers held out there for the next four days.

By noon the Germans had reached the streets of Berdorf and surrounded some 60 members of F Company under 1st Lt. John L. Leake, in the Parc Hotel, 100 yards east of the village. It was a three-story, fortress-like structure of reinforced concrete and sur-rounded by open ground—perfect for defense.

German grenadiers bypassed American strongpoints and captured a hill south of Echterbach. Some managed to reach the village of Lauterborn but were later forced to withdraw.

The swift current of the Sauer had caused the 320th Regiment to end up at Edingen, more than three miles downstream from where they’d entered the river. The delay brought the 320th onto the hills above Osweiler and Dickweiler well after daylight so that all of the American outposts in the area were able to pull back largely intact. At Osweiler, the German assault cost 50 men, and those who’d managed to gain the houses pulled back after dark.

Late in the morning, as two German companies began their attack on Dickweiler— defended by I Company—they came under mortar, small-arms, and machine-gun fire. The Germans made a half-hearted effort against the village until late afternoon, by which time the 3rd Battalion commander, Major Rice, had sent 15 men to the village from his reserve company riding on three Sherman tanks.

The Americans called in artillery, but it had limited effect as the supporting artillery battalions were widely dispersed behind the 4th Division front. Only 15 pieces from the 42nd Field Artillery Battalion and 12th Regimental Cannon Company were in range to support the 12th Infantry.

At noon, General Barton authorized 12th Infantry to commit its 1st Battalion, under Lt. Col. Oma R. Bates, out of regimental reserve. At the same time he gave Colonel Chance eight medium tanks and 10 light tanks, leaving the 70th Tank Battalion with only three mediums and a platoon of light tanks for other commitments.

Chance sent B Company, along with some tanks, toward Berdorf to relieve F Company in its hotel bastion and A Company, with the rest of the tanks, toward Lauterborn to reinforce G Company, whereupon the two companies were to drive to the relief of E Company inside Echternach. Because the Germans held the high ground on either side of the highway into Lauterborn, it took A Company the better part of the day to get into the village, and by that time it was too late to continue on. The men of E Company remained isolated in Echternach.

Barton asked Major General Troy Middleton, VIII Corps commander, for reinforcements, but Middleton only had the 159th Engineer (Combat) Battalion available. Nevertheless, elements of A Company, 159th Engineers, mounted on a platoon of light tanks, were ordered to open the road to Lauterborn and Echternach, the main supply route for the 2nd Battalion, 12th Infantry, under Major Gorn.

Early in the afternoon, B Company, 159th Engineers, mounted on five light and five medium tanks, set out to reach F Company, 12th Infantry. But when it reached the southern edge of Berdorf, it ran into grenadiers of the 1st Battalion, 423rd Regiment.

The troops of the 60th Armored Infantry faced seven battalions of the 276th VGD in their positions between the Sauer and the Schwarz Ernst gorge. The volksgrenadier division was deployed from Wallendorf to Bollendorf, with the 986th Regiment on the right, the 988th on the left, and the 987th in reserve. The division’s objective was to cross the Sauer, destroy the Americans, and gain the high ground to the southwest—about eight miles from Luxembourg City, from where they were to create a blocking position.

Since the bulk of the Seventh Army’s artillery was supporting its north wing, the preparation in the area of the 60th Armored Infantry was about 1,000 rounds, most of which fell on the battalion headquarters at Beaufort and on artillery positions farther to the rear, near Haller. This was sufficient to knock out phone lines within the battalion.

There was confusion among the German engineers manning the assault craft at Wallendorf as the morning mist made navigation difficult. The first assault companies crossed the river about 6:30 am. Once across, the 2nd Battalion, on the right flank of the 986th, headed west between Reisdorf and Bigelbach, making for the high ground in front of the village of Berens.

When the morning fog lifted, the armored infantrymen could see Germans swarming across the river near Wallendorf and near the village of Dillengen, just below the positions of A Company. The American artillery took both sites under heavy fire, but the Germans continued to cross. The small outpost at Hogenberg was quickly overwhelmed.

At daylight, the German assault force came under heavy fire from troops of the 3rd Battalion, 109th Infantry, on high ground north of the Sauer, delaying their advance. Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion had taken Bigelbach without opposition, but then came under fire from C Company, 60th Armored Infantry.

On the 986th Volksgrenadier’s left, the 988th Volksgrenadier crossed the Sauer around Dillingen, heading towards Beaufort and American artillery positions behind Haller. Dealing with the American guns was a priority, as their field of fire fell on the 276th VGD’s bridge sites at Dillingen and Wallendorf, and until they were removed none of the 276th’s artillery, or its four assault guns, could cross the river.

The men of the two forward companies, A and C, were soon aware that the wooded draws leading to their positions were thick with Germans. By mid-day, large numbers of volksgrenadiers had infiltrated through the gaps in A Company, as well as on both flanks, and forced back one of the company’s platoons.

The 60th’s commander, Colonel Collins, had little choice but to send his reserve, B Company, to fill the gap between A and C. Although B Company had several skirmishes with groups of volksgrenadiers, it managed to reach positions abreast of their fellow companies.

Meanwhile, the 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion at Haller continued to shell the German bridge sites. During the afternoon the 9th Armored Division commander, Maj. Gen. John Leonard, sent armored cars from A Troop, 89th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, to guard the approaches to Beaufort.

By dusk, the 988th Volksgrenadiers had made no more significant progress than had the 986th on the right, other than encircling the three American companies on the Sauer heights. Divisional artillery on the east bank of the Sauer provided supporting fire but was limited due to a shortage of ammunition.

As night fell, except for the outpost at Hogenberg, the 60th Armored Infantry’s positions remained intact. But Collins was increasingly concerned with the possibility of the Germans moving up the roads from the Schwarz Ernst gorge and isolating his companies and supporting artillery.

By early evening on December 16, the 12th Infantry continued to hold all its positions except those outposts overrun in the initial German assault, but it was clear that the Germans were continuing to build their strength.

So intense was the pressure against I and L Companies at Osweiler and Dickweiler that Colonel Chance sent the last of his reserve, C Company, to the 3rd Battalion’s CP to be ready to move to the two villages early the next day. The troops had no choice but to hold their positions as Barton ordered that there was to be “no retrograde movement” in the 12th Infantry’s sector.

Though hard-pressed, Barton was hesitant to call on his other two regiments, the 8th and 22nd Infantry, for assistance. But he did order the 22nd to release its reserve battalion, the 2nd, under Lt. Col. Thomas A. Kenan, to move north early the next morning to Junglinster, where it was to be joined by two tank platoons.

At the same time, three battalions of 155mm and two batteries of 105mm howitzers were ordered to move north to new positions. The 4th Engineer (Combat) Battalion and the 4th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop were alerted to be ready for commitment.

In response to the developing crisis in the 60th Armored Infantry’s sector, General Leonard, 9th Armored Division, ordered forward a company of medium tanks of the 19th Tank Battalion of CCA, for the next morning.

About midnight, General Middleton, VIII Corps, informed Barton that the next morning, CCA of the 10th Armored Division was to leave an assembly area in the Third Army’s sector, 35 miles from the 12th Infantry, and be available to Barton.

On the second day of the offensive, both sides committed more troops. The 212th VGD had started to place a bridge over the Sauer the previous day, but American artillery had shot out the structure before it could be used.

During the night the German engineers brought searchlights to the river opposite Echternach. They planned to build a bridge using the stone piers of what had been an ancient bridge site, but American shelling halted their efforts. Falling back, the engineers had to wait for daylight before beginning work at another site further downstream.

The division’s Füsilier Battalion, which had managed to cross the river, was committed against the 12th Infantry’s center in an attempt to drive a wedge through the American lines at Scheidgen.

The superior numbers of the 212th VGD—five battalions versus three of the 12th Infantry—were in the process of disappearing. With the 22nd Infantry’s 2nd Battalion on the move toward the threatened sector, as well as the possible use of Barton’s organic engineer battalion, the odds were growing even.

Barton also had an advantage in artillery, tanks, and tank destroyers, while German General Sensfuss was yet to get his assault guns or artillery over the Sauer.

American commanders’ intentions on the second day included using local reserves to rescue cut-off units, strengthening threatened units, and blocking exits from the Schwarz Ernst gorge leading to the rear of the American positions. Chance’s 12th Infantry was to rescue the men of F Company in the Parc Hotel outside of Berdorf and E Company in Echternach, as well as to reinforce the hard-pressed members of the 3rd Battalion in Osweiler and Dickweiler.

Three hours before dawn, Barton dispatched the 4th Engineer Battalion and 4th Reconnaissance Troop to Breitweiler, occupying the high ground above the gorge, not far from Müllerthal, behind the 12th Infantry.

The situation was reaching crisis proportions. Along the 4th Division front, the line was only secure at Lauterborn. Other units were isolated or cut off. At Berdorf, while elements of one company held out in the Parc Hotel, others defended the hat factory in Echterbach.

On the extreme end of the German left flank, the XIII/999 Fortress Infantry Battalion crossed the Sauer and advanced from the east on the village of Girst before being stopped by the American defenders.

Between the Sauer and the Schwarz Ernst gorge, the 60th Armored Infantry command was concerned about German movement up the gorge and egress along one of the three roads leading into the rear of the American positions—with the possibility of envelopment from the north—where, on the first day of the offensive, the Germans had eliminated an OP. During the night of December 16/17, Colonel Thomas Harrold, commander of CCA, 9th Armored Division, sent the 19th Tank Battalion’s light tanks, D Company, to screen the northern flank; attached a troop of the 89th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron to Colonel Collins’ 60th to patrol the road from the gorge to Collin’s headquarters at Beaufort; and sent another troop, plus self-propelled guns of B Company, 811th Tank Destroyer Battalion, to block the other two roads leading from the gorge.

During the same night, grenadiers of the 276th VGD worked south into the rear of Collins’ companies and occupied a ridgeline between Beaufort and the Sauer, cutting off the three companies of the 60th Armored Infantry.

On December 17, concerned over the 276th VGD’s lack of progress, Branderberger authorized the release of the 987th Volksgrenadiers from reserve to attack on the division’s left flank using the rocky defile of the Schwarz Ernst gorge to penetrate the American lines. The volksgrenadiers moved unopposed up the gorge to Müllerthal, a distance of about three miles beyond the Sauer.

From there they threatened the village of Waldbillig, not far behind the 3rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion. This forced Colonel Harrold to divert resources to meet the new threat, easing the 988th Regiment’s task. A half dozen Greyhound armored cars from Beaufort, sent to break through to the armored infantrymen, ran into a hail of fire.

As night fell, the volksgrenadiers of 1st Battalion, 988th, moved on Beaufort from the gorge. Colonel Collins ordered his headquarters troops to withdraw to Savelborn while cavalrymen of A Troop, 89th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, under Captain Victor C. Leiker, fought a rearguard action.

Leiker’s troops managed to hold for about two hours—long enough for the self-propelled howitzers of the 3rd Armored Field Artillery to displace from Haller to Savelborn, in the center of a new line that Colonel Harrold was forming between Ermsdorf and Waldbillig. Leiker’s force suffered the loss of 43 men and seven armored cars.

At the end of the day, a new defensive line was beginning to take shape along the 12th Infantry’s front. Osweiler and Dickweiler, on the right, were firmly in hand. On the left, a new task force from the 9th Armored Division, Task Force Luckett, under Colonel James S. Luckett, had established an anchor along the upper reaches of the gorge.

If there was a weakness, it was a gap between Osweiler and Consdorf, along the main highway from Luxembourg City to Echternach. In front of the line were several key positions still holding out—B Company and Lieutenant Leake’s small band at Berdorf, A and G Companies in Lauterborn, and E Company in Echternach.

With the 60th Armored Infantry effectively cut off, Colonel Harrold ordered a rescue operation with the only units he had available—B Company, 19th Tank Battalion; a company of the 9th Armored Engineer Battalion, mounted on halftracks; his Intelligence and Reconnaissance (I&R) Platoon; and one platoon each of light tanks and tank destroyers. They formed task forces under Captain John W. Hall and Major Tommie M. Philbeck, which set out towards Berens before dawn on the 18th.

The 1st Battalion, 986th, along with the regiment’s antitank (panzerjäger) company, armed with 54 Panzerfausts, was ordered to attack across the Ermsdorf-Savelborn road towards Medernach. The next morning, December 18, this force assembled near Savelborn.

As the 9th’s I&R Platoon was reconnoitering the planned route of attack for its task force, it was ambushed, the platoon leader killed, and the platoon virtually wiped out.

As a result, TF Hall was not aware of the trap they were headed into. Hall’s lead M-5 light tank was knocked out, blocking the road. During the subsequent fight, six or seven Shermans or assault guns were hit by panzerfausts and put out of action. The commander of the company of Shermans, Captain Arthur J. Banford, Jr., ordered a withdrawal to Savelborn.

Late in the afternoon, Harrold ordered the men of the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion to break out from their encirclement. Over the next two days, 400 men succeeded in making their way to American lines. In the three-day fight, the battalion lost close to 350 men, most of them during the withdrawal.

The new line of the 9th Armored Division’s CCA extended over seven miles—from Waldbillig north along the Schwarz Ernst gorge through Savelborn and Ermsdorf. But a four-mile gap still existed between CCA and the 109th Infantry on its left.

A new commander of the 276th VGD, Colonel Hugo Dempwolff, replaced General Möhring, who had been killed, and set about reorganizing the division. Lacking a bridge over the Sauer, on the night of December 18/19, he was able to bring forward three assault guns via a bridge in another sector. With their arrival, Colonel Dempwolff prepared for his division to return to the offensive, but higher command had other ideas.

The 276th VGD had taken the village of Beaufort and advanced to the outskirts of Breitweiler and Müllerthal. At 9:36 am, December 17, a German force of some five companies was reported moving along the Schwarz Ernst gorge near Breitweiler on the boundary between the 12th Infantry and 60th Armored Infantry. These were troops of the 987th Regiment, taken from the division reserve. C Company, 70th Tank Battalion, with eight tanks, was hurried to Breitweiler to reinforce the cavalry and engineers there.

Two platoons of A Company, 19th Tank Battalion, along with the assault gun and mortar platoons of 70th Tank, a battery of 105mm howitzers, the reconnaissance company of the 803rd Tank Destroyer Battalion, and the 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry, under Lt. Col. George Mabry, were hastily assembled at Colbet, one-and-a-half miles south of Müllerthal—organized as Task Force Luckett. (Colonel Luckett had been carried as an excess officer with the 9th Armored Division headquarters.) The task force was intended to prevent any further German advance beyond Müllerthal.

Early in the day, B Company, 12th Infantry, with five M-4 and five M-5 tanks from the 70th Tank, renewed the attack at Berdorf in an attempt to breakthrough to F Company, still encircled in the village.

In the center of the line, A and G Companies, 12th Infantry, with a platoon of five light tanks, started from Lauterborn along the road to Echternach. But German shellfire met the Americans. At the end of the day the relief force had only managed to consolidate positions in Lauterborn.

In Echternach, E Company, 12th Infantry, had occupied two strongpoints from which they harassed Germans attempting to move through the town. Troops from the 320th Regiment and the division füsilier battalion bypassed Echternach and Lauterborn in an attempt to cut the main road to Scheidgen. A platoon of A Company, 12th Infantry, posted the day before on Hill 313, southwest of Lauterborn, fell back to Scheidgen, but were eventually overwhelmed there.

At daybreak, C Company, 12th Infantry, in reserve, had moved out of Herborn en route to join the two companies beleaguered in Osweiler. As the company worked its way through the woods south of Osweiler, it ran into troops of the 2nd Battalion, 320th Regiment. One C Company platoon was lost in the action.

Meanwhile, in mid-morning, the 2nd Battalion, 22nd Infantry, under Colonel Kenan, arrived in the area of the 12th Infantry, de-trucked behind Osweiler and Dickweiler. F Company, mounted on tanks from the 19th Tank Battalion, and set out for Osweiler. Along the way they encountered a company of the German 320th Regiment, which they routed. In the process, they freed 16 members of C Company, 12th Infantry, and then pushed on into Osweiler. With these reinforcements, a new defensive line was organized on the hills east of the village.

During mid-afternoon, the remaining companies of 2nd Battalion, 22nd Infantry, started for Osweiler, advancing through woods atop a ridgeline southwest of the village. As the column moved, it encountered a German force in battalion strength and exchanged fire. The 2nd Battalion companies became separated, but the darkness ended skirmishing.

At the end of the day both Osweiler and Dickweiler remained in American hands as C Company, 12th Infantry, took positions on high ground between and slightly south of the two villages, extending the American line to the right. Despite achieving some initial surprise, the 212th VGD was unable to effect a deep penetration or disorganize the 12th Infantry.

Meanwhile, General Middleton directed General William H.H. Morris, Jr., 10th Armored Division, to send one combat command to Bastogne and the remainder of the division to the 4th Division to help drive the Germans back over the Sauer.

CCA, 10th Armored Division, under Brigadier General Edwin W. Piburn, moved north immediately in the area between the Schwarz Erntz gorge and the Echternach-Luxembourg road. CCA made good progress on its 75-mile drive from its assembly area at Thionville, France, but leading elements did not arrive in the 12th Infantry area until late in the afternoon of the 17th. Because of approaching darkness, an attack was postponed until the next day.

Piburn was to attack during the morning using three task forces—TF Chamberlain was to clear the Schwarz Ernst gorge; TF Standish, with the 61st Armored Infantry Battalion and a company of light tanks, was to push through Berdorf and then to Echternach; and TF Riley was to retake Scheidgen, link up with infantry in Lauterborn, and continue into Echternach. Given the concern for the Germans in the gorge, the first of Piburn’s task forces was to be committed there.

The counterattack began in a thick fog on the morning of December 18. On the left, TF Chamberlain, commanded by Lt. Col. Thomas C. Chamberlain, dispatched a small tank-infantry team, using elements from the 11th Tank Battalion, from Breitweiler into the gorge upstream from German-held Müllerthal.

The gorge was a formidable obstacle—a difficult transverse either by foot or vehicle, capable of being defended by only a few men and guns placed at key locations. The entrance to the gorge was so narrow that the tanks had to advance in single file. The task force came under a hail of antitank rockets and small arms fire, and the lead Sherman was knocked out.

The 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry, already in place, attempted to assist, driving back a few volksgrenadiers from the high ground. The fighting ended at dusk as Chamberlain’s men were forced to pull back.

TF Luckett, 9th Armored Division, advancing during the afternoon, was to bypass Müllerthal to the west and seize the wooded bluff above the gorge road north of Müllerthal. Before doing so, tank fire softened up the woods.

The task force under Lt. Col. Miles L. Standish, which had been assigned to assist the 2nd Battalion, 12th Infantry, moved towards Berdorf to link up with the 12th Infantry’s B Company to clear the village. Although elements of TF Standish were strafed by a pair of German planes, before noon they’d entered the village and contact with the infantry and six tanks already there.

The Germans responded by laying down smoke and a three-hour artillery barrage, disabling some tanks and halftracks and driving the Americans to cover. When the fire lifted the attack was resumed, but the Germans resisted stubbornly in house-to-house fighting as darkness brought the assault to a halt.

Meanwhile, members of F Company remained holed up in the Parc Hotel.

While part of TF Standish was engaged in Berdorf, more Yanks attacked through heavy underbrush toward Hill 329, east of Berdorf, which overlooked the road to Echternach. But the American infantry was checked halfway to their objective by machine-gun and artillery fire.

The task force under Lt. Col. John R. Riley—a company each of medium tanks and armored infantry—made good progress in its attack from Scheidgen to Lauterborn. Scheidgen was retaken early in the afternoon, virtually without a fight, since the German battalion that had previously seized the village had departed to the south.

Once inside Scheidgen, TF Riley delayed advancing to Echternach, as Riley thought that it was too late in the day to continue. The task force held up for the night along the road to Echternach at a mill where G Company had its CP. Riley did send two tanks with two squads of infantry into Echternach to contact E Company, 12th Infantry.

The E Company commander, 1st Lt. Morton A. Macdiarmid, had established his headquarters near the edge of the town in the hat factory along the road to Lauterborn. Although his headquarters was not under pressure, Macdiarmid had withdrawn some of the riflemen capable of making it back to the CP, but some outposts, including one platoon, were still cut off.

Macdiarmid didn’t want relief from defending Echternach, since he had orders to stay put, but rather wanted tanks to help extricate the cutoff 1st Platoon. But the commanders of the two tanks from TF Riley were unwilling to risk their vehicles in the town’s narrow streets, though they promised to return the next morning.

Meanwhile, five tanks and two companies of the 159th Engineer Battalion launched a surprise attack against Hill 313, overlooking the road to Lauterborn; thick fog prevented the Americans from taking the hill.

General Barton attempted to strengthen 12th Infantry’s right flank in the Osweiler-Dickweiler area. The 2nd Battalion, 22nd Infantry, which had met the German column in the woods west of Osweiler the day before, headed for the village early on December 18. Upon its arrival, the American garrison then consisted of a tank company and four under-strength rifle companies.

As the American reinforcements stiffened the right flank and the armored forces grappled to wrest the initiative from the Germans on the left, the Germans attempted to widen and deepen the penetration into the 12th Infantry’s center, shouldering their way south between Scheidgen and Osweiler.

The burden of the advance was carried by the 320th Regiment and the advance guard of the 316th Regiment, which General Sensfuss had “pried” from the Seventh Army’s reserve—but it would be another 24 hours before that regiment crossed the Sauer.

The first appearance of German forces deep in the center of the 12th Infantry occurred near Maisons Lelligen, northwest of the village of Herborn, where the 12th’s Regimental Cannon Company came under fire while on the move. The cannon crews responded by unlimbering their guns and fighting a three-hour engagement at ranges as short as 60 yards before withdrawing.

Further west, German elements that had come up from Scheidgen surrounded the headquarters of the 2nd Battalion, 22nd Infantry, along with a platoon of 57mm towed antitank guns, in Geyershof. But tanks en route to Osweiler intervened, allowing the battalion headquarters personnel to withdraw to Herborn.

German General Sensfuss apparently didn’t realize that his men had achieved a breakthrough. But the German battalions, already under-strength, had taken heavy losses during the day and were in no condition to exploit their gains.

By the end of the 18th, the two American companies in Berdorf had been reduced to just 79 men, while the companies of 2nd Battalion, 22nd Infantry, counted an average of only 60 men. Meanwhile, the remainder of the German 316th Regiment began to cross the Sauer, moving up behind the center of the 212th VGD.

The two left-flank divisions of the German Seventh Army were nearly stalled, their engineers having had great difficulty placing bridges across the Sauer due to American artillery fire. The 276th VGD managed to wrest the village of Savelborn from CCA, 9th Armored Division, after which they turned back counterattacks by TFs Hall and Philbeck.

During the night of December 18/19, elements of the 9th Armored Division withdrew to a new line on the left of the 4th Division; however, the division did not abandon its right flank anchor at Waldbillig. Dealing with the German 987th Regiment and eliminating or containing the German forces in the Schwarz Erntz gorge was left to the 4th Division and CCA, 10th Armored Division.

On December 19, Patton turned his Third Army north toward the southern shoulder of the German penetration—the “Bulge.” Command of VIII Corps passed to Patton, who created a provisional corps headquarters to control the Corps’ troops still in Luxembourg and others moving to the area.

Under the command of the 10th Armored Division’s General Morris, the provisional headquarters controlled Morris’ division, except for CCB at Bastogne; CCA of the 9th Armored Division; the 109th Infantry; and the 4th Infantry Division.

Retaking the territory seized by the Germans during the first four days of the counteroffensive was no longer a priority for the Americans. Their mission now was to hold a line in order to allow time for troops from Third Army to arrive. General Barton was to form a main line of resistance extending from Osweiler and Dickweiler through Scheidgen and Consdorf to positions held by TF Luckett overlooking the Schwarz Ernst gorge at Müllerthal, while the 10th Armored Division’s CCA was pulled back into reserve. This meant withdrawing from Berdorf, Lauterborn, and Echternach.

Also on December 19, the commander of the LXXX Corps, General Beyer, ordered his forces into a defensive posture. Although the 212th and 276th VGDs had failed to push the shoulder of the penetration as far south as originally planned, Beyer believed they had gone as far as they could. He also calculated that the Americans were preparing a counterattack and that he needed his men to dig in.

But two tasks remained. Beyer wanted the 276th VGD to take Waldbillig in order to afford the troops in the gorge at Müllerthal a route of egress if needed. The other task was to eliminate the Americans holding out in Echternach.

Early on the 19th, TF Luckett made another attempt to advance into the gorge. The maneuver involved a flanking movement intended to seize the high ground overlooking Müllerthal.

Troops of Colonel Mabry’s 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry, with tanks and artillery support, attacked east from Waldbillig to take the wooded nose around which looped the Waldbillig-Müllerthal road. The advance, over open fields, was eventually checked by heavy shellfire.

Mabry then shifted his attack to the right to bring the infantry through the draw that circled the nose. E Company, which had only about 70 men left, was still the strongest in the battalion and led the assault. Despite losses, E Company drove forward, clearing the Germans from the lower slopes before being recalled.

Barton then called off the attack and assigned TF Luckett the mission of denying the Germans the use of the road net through Müllerthal. Luckett responded by deploying his troops along the ridge southwest of the Müllerthal-Waldbillig road. Log abatises (entanglements), mined and covered by machine guns, were erected to block the valley road south of Müllerthal.

Meanwhile, the village of Christnach, a few miles south of the Sauer, fell to elements of the 276th VGD, while TF Chamberlain was so battered that the unit retired to Consdorf.

A tank-infantry counterattack by TFs Standish and Riley in the Berdorf and Echternach areas resumed while heavy fog covered German operations. This included the assembly of the 316th Regiment behind the 212th VGD center during the day. Also, by the middle of the afternoon, a bridge had finally been erected at Edingen.

At Berdorf, a team from TF Standish and a platoon of armored engineers set to work mopping up German troops of 1st Battalion, 423rd Regiment, who had holed up in houses on the north side of the village. The work required pole charges and tanks to blast through the walls of houses. The infantry then went to work with grenades and small arms. As the Germans were slowly driven back, they were assisted by the fire of nebelwerfers (rocket artillery) of the 8th Volkswerfer Brigade.

TF Standish returned to the attack in the direction of Hill 329, along the Berdorf-Echternach road, where they had been checked by flanking fire the previous day. They destroyed a German machine-gun position as the attack reached the ridge before Hill 329, but the advance halted short of its objective in order to free the tanks and halftracks to evacuate the wounded. The tanks of the task force were then involved in a night-long firefight with the 2nd Battalion, 423rd Regiment, which had been concentrated in preparation for the capture of Consdorf.

Colonel Riley sent tanks carrying infantry to the edge of Echternach on the morning of the 19th, established contact with E Company, and covered the withdrawal of outlying detachments to the hat factory. The 12th Infantry’s Colonel Chance gave permission for E Company to evacuate Echternach.

Meanwhile, the Germans began an assault on the hat factory. Two volunteers were sent to Lauterborn with a request for help, but instead of receiving relief, E Company was ordered to fight its way out during the night.

Lieutenant Leake and his 60 men continued to hold the Parc Hotel in Berdorf as German artillery landed around the building and panzerfausts tore holes in its east side. On the night of December 19/20, a dense fog descended, the volksgrenadiers using it to approach the hotel. Before daylight the next morning, an explosion blew a large opening in the hotel and the Germans launched an assault. For half an hour the fight was desperate; then it stopped as quickly as it had started.

The Germans made no move to push deeper into the center of the 12th’s lines during the day. In the meantime, combat engineers in Scheidgen returned and occupied Hill 313 without a fight. By nightfall, the situation seemed much improved as both flanks of the 4th Division held steady while the German attack lost momentum.

On December 20, the 4th Infantry and 10th Armored Divisions sought to disengage their advance elements and regroup along a stronger line.

At the same time, elements of the 276th VGD, having received several assault guns as well as rocket and artillery support, struck through Müllerthal to Waldbillig—the boundary between the 4th Division and the 9th Armored Division—in an attempt to push the right wing of the LXXX Army Corps forward to where the road net leading east to the Sauer might be denied the Americans.

In savage fighting, troops of the 212th VGD finally drove the Americans from Berdorf. In Echternach, the division’s füsilier battalion prepared to conduct an attack, supported by four assault guns. At 2 pm, the German assault guns opened a devastating fire on the buildings held by the E Company riflemen and the machine gunners and mortarmen of H Company. Compelled to surrender, prisoners included 111 officers and men of E Company, plus 21 men of H Company.

At the same time, F Company, 12th Infantry, continued to hold its position in the Parc Hotel, while G Company, with only 40 men, managed to withdraw from the town. With the coming of daylight, the Americans found the Germans dug in to the west of the hotel. Leake and his men soon abandoned their position and joined B Company and armored elements in Berdorf just after nightfall, then withdrew to Consdorf.

At daylight the 1st Battalion, 423rd Regiment, which had been brought in from the Lauterborn area, initiated a counterattack against TF Standish at the edge of Berdorf and recovered all the ground lost during the previous two days, until American artillery fire drove the German troops to cover.

Although the evacuation of Berdorf was part of the 4th Division plan for redressing its line, the actual withdrawal was not easy. The Germans had cut the road to Consdorf as elements of TF Standish were withdrawn from an attack on Hill 329 and spent most of the afternoon clearing an exit for troops in Berdorf.

Shortly after dark, B and F Companies, 12th Infantry, along with 10 engineers and four squads of armored infantry, loaded onto 11 tanks and six halftracks and made their way to the 4th Division line northeast of Consdorf.

The Germans had gained control of most of the road network just beyond the Sauer, but too late. The new American line, running from Dickweiler through Osweiler, Hill 313, and Consdorf, to south of Müllerthal—though weak in the center—was well anchored on the flanks; German artillery was unable to drive the Americans out of Dickweiler.

At Bech, between Junglinster and Echternach and behind the American center, General Barton had placed the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Infantry, in reserve, having further stripped the 4th Division’s right. In and around Eisenborn, CCA, 10th Armored, was also assembling to counter possible German threats.

The German Seventh Army’s assault reached its high-water mark on December 21 and was halted due to the growing threat from Third Army. In its furthest penetration, the 276th VGD had nearly reached the village of Savelborn, but was stopped by dug-in American tanks. A bid by the 10th Armored and 9th Armored Division’s CCA to take Waldbillig was stopped with great difficulty, the American armor taking over 100 prisoners.

At the southernmost point of the German advance, the 212th VGD moved in mass along the Echternach-Luxembourg highway. The German assault carried through Lauterborn and then continued south; however, the U.S. 4th Division and CCA, 10th Armored, rallied to repulse German advances toward Consdorf and Osweiler, parrying the German attacks with counterblows of their own. Elements of the U.S. 5th Infantry Division, XII Corps, began arriving to reinforce the overtaxed 4th Division.

The LXXX Army Corps had fought itself out. Some infantry companies reported strength of only 30 to 40 men.

The Germans had failed in their initial objective of overrunning American artillery or at least forcing its withdrawal to positions from which it could no longer interdict the German bridge sites. The failure to open the bridges over the Sauer within the first 24 hours had then forced the German infantry to fight without heavy weapons or armor support.

But American success along the Sauer came at a cost. In six days of fighting, the units on the southern shoulder lost over 2,000 killed, wounded, or missing. German casualties were believed to be somewhat higher, although exact numbers were unknown; about 800 German prisoners were taken.

The stubborn defense of the towns and villages close to the Sauer blocked the roads that were essential to the Germans’ moving through the rugged terrain and barred a quick sweep into the American rear.

If the Seventh Army had succeeded in achieving its objectives, Patton’s Third Army would have been hard-pressed to firm up the southern shoulder while also attempting to break through to the 101st Airborne Division at Bastogne.

For its actions in holding the southern shoulder of the Bulge, the 12th Infantry Regiment received a Presidential Unit Citation. Many more certainly deserved it.