By Robert Heege

Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, the nephew and namesake of the great Napoleon, once said, “March at the head of the ideas of your century, and these ideas follow you and support you. March behind them and they drag you after them. March against them and they overthrow you.”

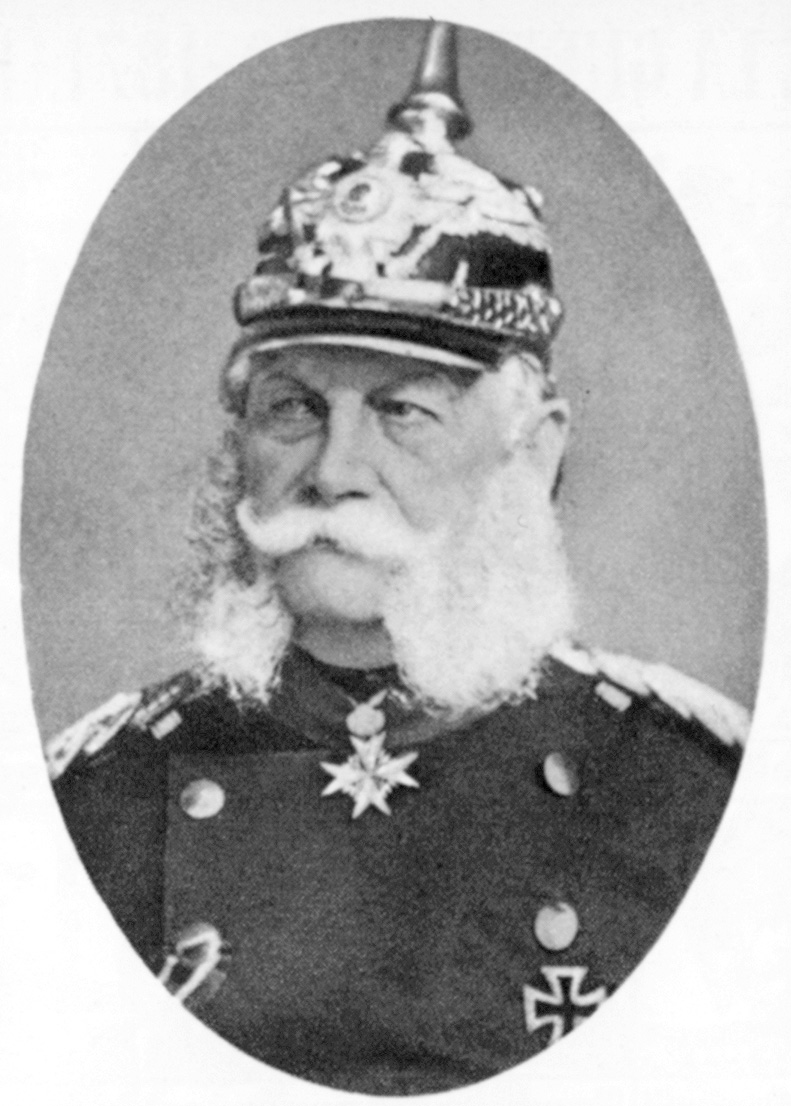

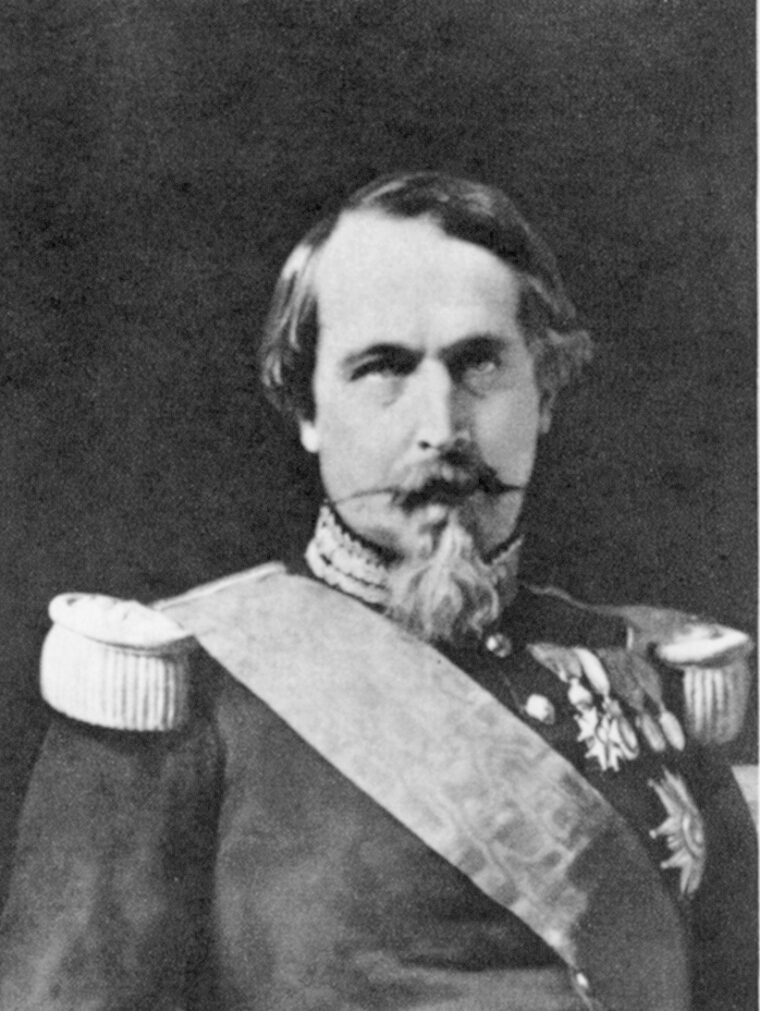

In the spring of 1870 all appeared resplendent for Louis at the Imperial birthday celebrations held at Châlons. There, amid an adoring throng of beaming sous-lieutenants, jewel-bedecked matrons, and field marshals weighted down with gold braid and moustache wax, France’s second emperor stepped forth once again, in the manner of the ancient Caesars, to receive the heartfelt tribute of his valiant legions. Looking out on an electrifying landscape of gleaming cuirasses, magnificent plumed helmets, and everywhere the tricolor festooned with streaming battle ribbons testifying to 18 years of uninterrupted glory, it must have seemed to the faithful that it would all go on forever.

As the seemingly invincible host of Imperial dragoons, lancers, and hussars shouted themselves hoarse with cheers of praise for their sovereign, there was at least one among them who was not so sure, though betting all the same that his luck would hold. That man was the Emperor himself.

Louis Napoleon’s Winning Streak

It would be all or nothing. Up to that point, this had been a strategy that had served Louis Napoleon well. In fact, it had been the making of him. For if he inherited little else from his immortal ancestor, it can be reliably reported that one outstanding characteristic had become readily apparent early on: He had the Bonaparte luck and a knack for being in the right place at the right time. All in all, it had been a remarkable winning streak.

Owing to the 1848 revolution that ousted the Bourbons, Louis returned from lifelong exile and at age 40 was elected to lead the French Republic. Three years later he seized absolute power. Named Emperor by plebiscite, Louis, now “Napoleon III,” proclaimed the Second Empire in 1852. For nearly 20 years, though the world at large remained a swirling confluence of events, France stood at its becalmed center, confident, stalwart, and serene. Britannia may have ruled the waves, but on the European continent and beyond, all eyes looked to the French. Long unrivaled in matters of culture and cuisine, the nation over which Napoleon III ruled was similarly without equal in terms of military prestige. Decidedly martial in tone, the Second Empire was like a perpetual display of soldierly Élan, a never-ending pageant of colorful uniforms and soaring anthems, galloping along in one long, saber-rattling military review.

In a way, reputation became reality, for it was during these years that the intensive study of the strategies and tactics of the first Napoleon became such an essential rite of passage for military cadets. From one end of the globe to the other, French influence was everywhere. When the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, so soundly defeated in the Crimean War, decided to overhaul the Turkish Army in 1856, he hired French military advisers. In 1868, when the Japanese, emerging at last from centuries of calcified isolation, set themselves to creating a modern fighting force from the ground up, they too looked to the French. In North America, the French could rightly boast of their disciples on either side of the Mason-Dixon Line. When Union and Confederate armies clashed, both sides wore the ubiquitous French forage caps, the kepi, and a uniform that was decidedly Gallic in style. Each army even boasted whole regiments of gaily clad “Zouaves” wearing the distinctive headgear and wide pantaloons of France’s Algerian colony in North Africa.

Napoleon III Believed in “the Principle of Nationalities”

Accordingly, it had come as no surprise to anyone that when Napoleon III sent his vaunted army against the Austrians in 1859, in an attempt to drive their occupying forces out of most of northern Italy, the result was victory. For the self-appointed champion of Italian nationalists, this short, sharp little war had merely been in keeping with his avowed belief in “the principle of nationalities.” But that victory, which seemed for so many to have been a foregone conclusion, masked some uncomfortable truths. The fact was that when the two foes faced off against each other, at Magenta and again at Solferino, the extremely costly contest had actually been a lot closer than most observers had realized.

For all their supposed superiority in the profession of arms, the French war machine had, in reality, proved to be just slightly better led and only marginally better prepared than the more lumbering Austrians. This seemed to have been lost on most of the foreign correspondents of the day, and was, of course, blithely ignored by the French themselves, who hailed their Emperor as a conquering Caesar when he returned to Paris in triumph at the head of his troops.

The great gambler had survived to play again another day. Scarcely seven years later, in 1866, a terrifying vision of the future took shape in the lands of the Hapsburgs that provided cold comfort to the Emperor of the French. There, at Sadowa, in a military campaign of lightning speed and frightening efficiency, the North German Kingdom of Prussia, determined to secure political dominance over her Southern German cousins and end Austrian meddling in the region once and for all, caught the hapless, thoroughly antiquated Austrian Army completely off guard and smashed it to pieces, forcing the Austrian Kaiser, a thoroughly humiliated Franz Josef II, to sue for peace with almost unseemly haste.

The lesson was not lost on Napoleon III, who knew in his heart, if no one else did, that at Magenta and Solferino, his army had only barely managed to prevail over the same Austrian regiments that the Prussians had just so handily thrashed. When, in the aftermath of the Battle of Sadowa, it became obvious that the Prussian infantryman, equipped with the Teutonic gunsmith Dreyse’s latest repeating rifle design, the so-called needle gun, had simply outclassed his muzzle-loading Austrian counterpart in terms of accuracy, range, and rate of fire, Napoleon III championed the development of the chassepot, a .43-caliber cartridge-firing rifle that, with twice the range, was actually superior to the needle gun. Within four years, one million of these breech-loading rifles had been produced. Moreover, taking note of the American Gatling gun that had only recently made its debut in the last stages of the Civil War, a French version of this embryonic machine gun, a 26-barreled, crank-operated mankiller known as the mitrailleuse was also developed and hurriedly rushed into production.

Dangerous New Rival Unexpectedly Appeared on the Continent

Although he was loath to admit it, Napoleon III, alarmed by the sudden shifting of the balance of power in Central Europe, had clearly been hedging his bets. Looking over his shoulder from the heights of his once unassailable position, he could clearly see that a dangerous new rival had unexpectedly appeared on the Continent to challenge his nation’s previously unquestioned dominance. Over the course of the next few years, as an increasingly arrogant Prussia began flexing its newfound muscles, it became more and more obvious that the French rooster and the Prussian eagle were predestined to face off against each other one day and let the feathers fly.

Accordingly, the French General Staff, at their Emperor’s urging, went cap in hand to the Corps Legislatif, the country’s legislative body, in hope of securing enough funding for a complete overhaul of the army. The legislators, relishing the new powers that recent liberalizing government reforms had given them, and more concerned with fighting the war on poverty than with the army’s incubating obsession with the Prussians, were prepared to offer the generals no more than a pittance.

Despite this rebuff, the High Command remained supremely confident that the army would always be able to adjust. After all, around the globe, this was a belief shared by almost everyone. Sadowa notwithstanding, the universally accepted wisdom continued to hold that in the event of hostilities, the only possible result would be a second Battle of Jena—a French victory as resounding as that of the first Napoleon, and a similarly bitter defeat for the newly resurgent Prussian upstarts.

Chancellor von Bismarck, Ruthless Visionary

In the Prussian capital of Berlin, however, a slightly more optimistic forecast was beginning to gain its proponents. Its champion was no less than the Prussian Chancellor himself, Count Otto von Bismarck. A ruthless visionary for whom the war with Austria had been nothing short of a stepping-stone toward the realization of a long-cherished goal that he had nurtured for years, Bismarck set himself to the task of forging the divisive hodgepodge of independent German kingdoms into a unified nation, a German Empire that would be cobbled together under Prussian hegemony, whether they liked it or not.

And so it was that in the spring of 1870, the flower of the French Army came together once again at the great Champs Militaire at Châlons to fête their Emperor. They could not know that this grand gathering was to be the last of its kind, or that, compelled by national honor to ignore his own better judgment, Napoleon III, one of the greatest political gamblers France had ever known, was about to become the unwitting captive of both his illustrious pedigree and his own carefully created legend. Within a few months, he would find himself wagering everything—crown, country, and empire—on one final desperate roll of the dice.

The Hohenzollern Candidature

In stark contrast to France’s somewhat enervated performance in the area of military reform during the late 1860s, the years leading up to 1870 were full of dramatic change for the Prussian Army. Universal military service became the law of the land. In addition, Bismarck’s efforts at corralling the smaller German states into some kind of Prussian-dominated federation were beginning to bear fruit. King Wilhelm I, by now Commander-in-Chief of the North German Confederation, possessed an army of nearly one million superbly trained, well-equipped fighting men—the largest in Europe.

But that was only a part of the story. Unlike its French counterpart, Wilhelm’s General Staff was a model of discipline and efficiency. A revolutionary clockwork-like system of mobilization was perfected, making full use of the latest technical advances in communication and deployment. For the first time in Europe, the telegraph and the railroad would be exploited to their fullest potential, making them an integral part of Prussian strategy. By the end of the decade everything was in place. All, that is, except a reason for Bismark to make his grand move.

In the summer of 1870, this chance literally landed in his lap. Two years earlier, Isabella II, the corpulent, debauched Queen of Spain had been pitched from her throne in a coup led by her exasperated Prime Minister, Juan Prim. A staunch monarchist, Prim was motivated by a desire to replace Isabella with a sovereign who would prove to be worthy of the Spanish throne—not a disgrace to it. For centuries, the crazy quilt of small independent German states that blanketed the map of Central Europe had provided its neighbors with one invaluable service: They were always able to supply teetering dynasties with suitably royal consorts and, in a pinch, kings. The thrones of Greece, Denmark, Belgium, and Great Britain, to name just a few, had all been reliably and successfully supplied with heads suitable for crowning by what may arguably have been called the royal stud farm of Europe. The trouble was that the vagaries of Spanish politics made for a hard sell.

Since the time of the portly Isabella’s ouster, Prim had been making the rounds of nearly every Catholic royal house in Southern Germany until, late in 1869, he got around to the House of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, the Catholic branch of the royal family, the Hohenzollerns, that had ruled Prussia for centuries. After sizing up a gaggle of possible contenders, he set his cap on Prince Leopold, a likable, malleable young man barely out from under the shadow of his domineering father, Prince Anton. Prim had barely made the offer, however, when the French ambassador to Prussia got wind of it. Napoleon III, already concerned by the potential threat posed by the Germanic host at his front, was in no way inclined to tolerate another settling down at his back door. His ambassador duly informed the Prussian chancellor, Bismarck, to instruct the interested parties that he considered the proposal to be “essentially anti-French” and that his nation would not accept it. Napoleon III had gambled and won. Reflexively, Prince Leopold backed away from the table and declined the offer.

The more Bismarck thought about it the more he began to realize that he had missed his opportunity. For here had been a chance to make the maximum amount of mischief with the greatest amount of political cover. He vowed that if the fates were to grace him with a similar chance to cajole all the German states into a united front they would not find him napping again. Incredibly, three months later, the fates visited Bismarck once more—and they brought the furies with them.

Bismarck Seizes the Reins, Ups the Ante

In February 1870, Prim, having had no luck elsewhere, approached Prince Leopold a second time. On this occasion, he was sure to include King Wilhelm I of Prussia, the head of the family, and his ubiquitous chancellor, Bismarck, in the discussions, which were now conducted in the strictest confidence. Seizing the reins, Bismarck upped the ante. On March 15, he convened a secret conference, making sure that Field Marshal von Roon, the Minister of War, and Field Marshal von Moltke, the Chief of the General Staff, were also in attendance. To his chagrin, Prince Leopold had decidedly cooled and refused the offer a second time. But Bismarck was not about to be trumped again.

Over the course of the next few months, he continued to work on the reluctant Prince’s father, appealing to his patriotism, stroking his vanity, until he finally wore him down. Prince Anton, having been won over by Bismarck, essentially ordered his son to accept the Spanish throne as a matter of duty. Prince Leopold dutifully complied and Prim had his soon-to-be king. On June 19, the young prince wrote to King Wilhelm in Berlin to request his blessing. The old king, despite some serious misgivings, wrote back with his approval. This was the kind of news that couldn’t be kept under wraps for long. Prim decided to let the cat out of the bag himself; he informed the French ambassador.

The news reached Paris on July 3. The result was a firestorm. Although the Emperor appealed for calm, his own ministers would have none of it. In the Corps Legislatif, one incendiary speech followed another. The Duke de Gramont, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, shouted to the rafters that “France would go to War sooner than see a Hohenzollern rule at Madrid.” The heads of state of half a dozen nations began beseeching Prince Leopold to withdraw himself from the enterprise and thus preserve the peace of the European continent. Incredibly, many of them had been secretly asked to do so by none other than Napoleon III himself, who seems to have been the only man in France at the time who was not screaming for blood. The Emperor was, in fact, attempting to keep the peace by making a clandestine diplomatic end-run around his own government. Amazingly, he succeeded. The hapless Prince Leopold bowed out yet again. The Bonaparte luck had held.

The Ems Telegram

It might have ended then and there. If skillfully handled, the whole affair might have gone into the history books as a minor political footnote, a soon-to-be-forgotten episode ending with a diplomatic victory, of sorts, for the Second Empire. Instead, it was to prove the ruin of it. Not content with merely getting their way, French politicians in the Corps Legislatif, their blood running hot, began pressing the case that national honor demanded a Prussian guarantee that the question of “the Hohenzollern candidature,” as it was now being called, would never again be raised.

The Duke de Gramont, almost in a fit of pique, ordered the French ambassador in Berlin to request an audience with King Wilhelm to extract just such a promise. The request was granted and a meeting scheduled for the morning of July 13 at the old spa town of Ems. Unable to wait until the appointed time, the French Ambassador, Count Benedetti, button-holed the Prussian King during his habitual early morning walk through the Kurgarten. Wilhelm, who was never one for putting on royal airs, was, as usual, the quintessential German burgher: erect, correct, and courteous. He listened politely, expressed his relief that the situation had seemed to resolve itself and that he viewed its outcome with complete equanimity.

But when Benedetti, true to his brief, attempted to wheedle some kind of official promises out of Wilhelm—in effect, a royal apology—something in the old man stiffened. As a young man he had actually taken part in the Napoleonic Wars 56 years earlier. At heart, he was a soldier still, and a proud one. His pale blue eyes narrowed, zeroing in on the ambassador, and Benedetti could see that beneath the venerable monarch’s robust set of snow white whiskers, his jaw had visibly tightened. His response was a polite but unequivocal no. When Benedetti pressed him further, he tipped his hat wordlessly and walked on, leaving the count to stammer impotently on the pathway.

Later that day, King Wilhelm sent a telegram to his chancellor describing his irritating encounter with the French ambassador. What happened next is the stuff of spy novels. Bismarck edited and craftily reworded the text of the telegram until it read like a poison pen letter, an unmistakably insulting swipe that would be sure to bait any Frenchman. Then he leaked it. Not only did he release its contents to the German newspapers, in a clear gesture of monumental disrespect, but he also made sure to send copies of it to all of Prussia’s ambassadors abroad, who in turn released the text to the foreign press. He was deliberately bearding an entire country, daring them to try and do something about it. A proud nation, jealous of its reputation, was being made into a laughingstock. He knew it would have to respond. He was counting on it.

French Honor Is at Stake

He did not have to wait long. The following day, July 14—Bastille Day—the deputies of the Corps Legislatif demanded satisfaction. Napoleon III’s senior council of ministers sat huddled around a table staring at the mobilization orders they had just drafted. For several hours into the night they vacillated, but it seemed obvious to them that nothing short of French honor was at stake. They had no choice but to give the order.

With the stroke of a pen, a fearful series of events was being set in motion and the metronome of the Second Empire had begun to tick. Unwilling to wait for the other shoe to drop, Wilhelm, at Bismarck’s urging, had somberly issued orders of his own. In anticipation of possible hostilities, the Prussian mobilmachung had already sprung to life. Bound by treaty and boxed in by Bismarck’s machinations, the Southern German Kingdoms of Bavaria and Baden were compelled to follow suit, ordering full mobilization on July 16, with Württemberg following suit on the 18th. That very day, France declared war on the lot of them. Provoked beyond all endurance by a cunning and skillfully executed conspiracy into being the first one to actually sever the peace, she was like a majestic stag being maneuvered to its doom by a patient hunter. As the campaign began, she could not see that for all her magnificence and courage, she was but one short step away from toppling into the deadfall.

The Sin of Pride

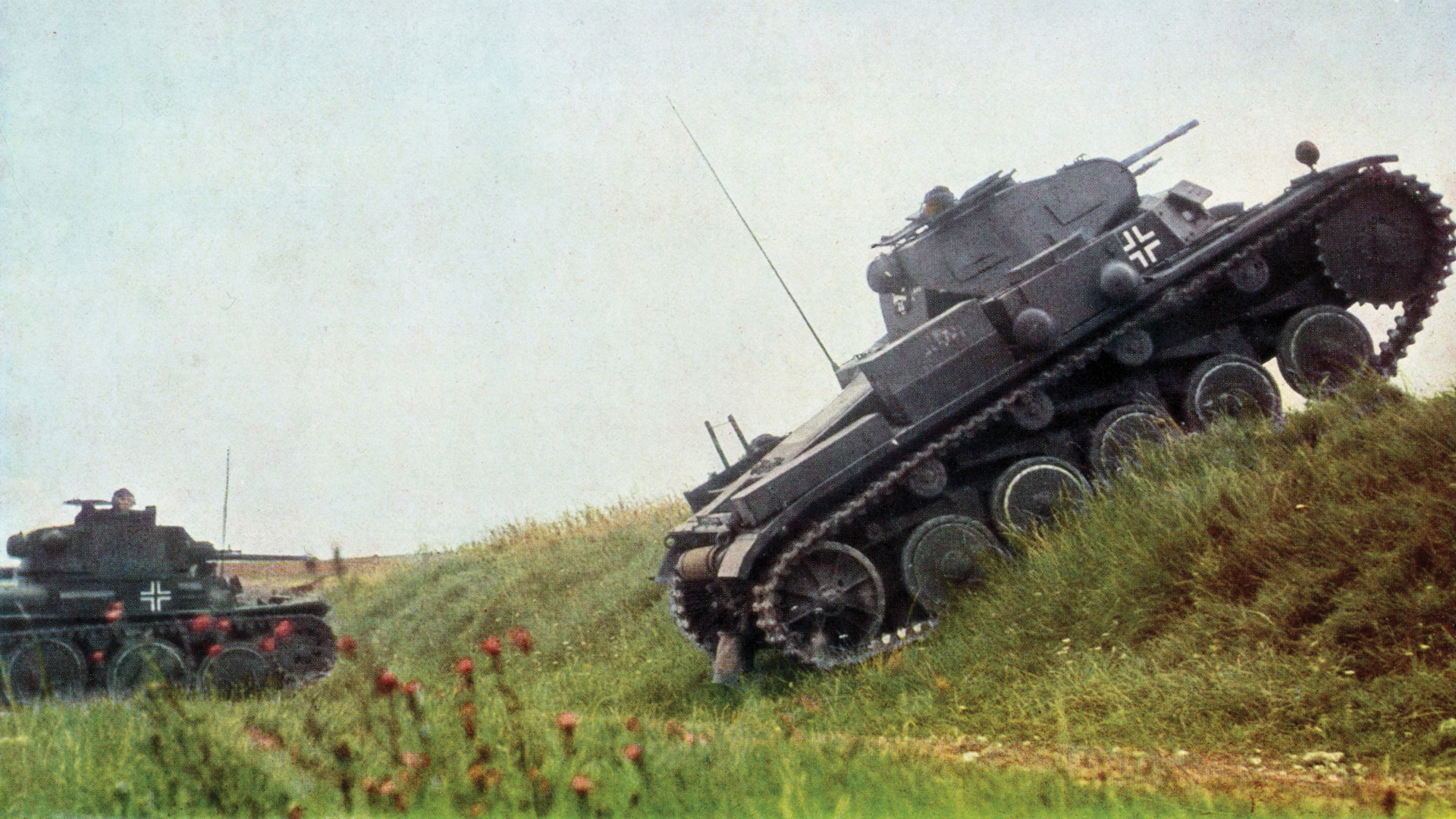

In sharp contrast to their Emperor, who is said to have wept openly in the final hours of peace, the population of Paris went mad with joy at the news that their nation was now at war with the Prussians. As they shouted themselves hoarse with cries of “Vive la France!” and “On to Berlin!” nobody seemed to notice that while their own army’s mobilization was a portrait of confused lethargy, its Prussian counterpart had sprung to life like an industrious beehive of purposeful, skillfully coordinated activity. It didn’t seem to concern them that in the two weeks that followed the mobilization order, the French Army of the Rhine, as the chosen instrument of Gallic retribution was now being called, had only managed to assemble and equip a little more than half of its men. The fact that in roughly the same period of time 1,183,000 of their adversaries had been outfitted in Prussian blue and issued the characteristic spiked helmet, the pickelhaube, and that 400,000 of them were already massed on the French border scarcely caused a ripple of anxiety. That they were backed by an arsenal of 1,440 cannon, including 500 of a revolutionary steel-cast, breech-loading design by the armaments wizard Alfred Krupp, likewise, worried no one.

King Wilhelm’s High Command had nearly taken it as holy writ that the vanguard of a coming French onslaught would soon be besieging their headquarters at Mainz. They had done all they could, defensively, to brace themselves for an anticipated spoiling attack reaching from the Saar Valley to the Rhine. The Prussians watched and waited with a growing sense of astonishment as the days went with no real signs of any kind of enemy activity. Slowly, it began to dawn on them that the opening moves in this deadly game might well fall to them. Commenting on this surprising turn of events, Friedrich Wilhelm, the Prussian Crown Prince, spoke for a great many in the Prussian ranks when he confessed to his diary his utter amazement that for all of the meticulous planning that had gone into the formulation of their initial defensive posture, it was becoming increasingly obvious that the initiative was theirs to take. That “we shall be the aggressors,” he wrote. “Whoever could have thought it?”

If, indeed, the Prussians were beginning to see the shape of things to come from an entirely new perspective, the French could not have been more blind to the perilousness of their situation. Vainglorious and fatally arrogant, they were the proud inheritors of the most storied reputation for martial valor since the days of Alexander. Accordingly, they saw no reason why they should be hurried into the bloody business of smiting the hopelessly provincial Goths who had dared to challenge their time- honored, globally acknowledged preeminence in the profession of arms. Élan would carry them through. What did it matter if the vaunted French Army actually had 30 percent fewer field pieces than their Prussian opponents? After all, they had the blood of their legendary forefathers—the great Napoleon’s legions—running through their veins.

The French Army’s Achilles Heel

Unfortunately for the French, it did matter. In fact, it mattered a great deal. The truth was that their armed forces had failed to keep pace with the most recent technical advances in the field of military ordnance, and were still relying on muzzle-loading bronze cannon, which, apart from the rifling of their barrels, were not all that different from the ones the French Army had employed the last time they’d fought against the Prussians at Waterloo in 1815. As was soon to be made devastatingly clear, the French cannon were completely and utterly obsolete, especially in comparison with the 500 steel-cast breech-loaders in use in the Prussian Army by 1870.

That was their Achilles heel. For nearly two decades, the French Army, like their Emperor, had slavishly worshiped at the altar of the first Napoleon, effectively aping a storied romantic past that had died at the hands of Wellington and von Blucher 55 years before. Having dedicated themselves to reviving the grandeur of that lost era and of refighting the great campaigns of yesteryear, they had failed to safeguard their own future.

So it was that on July 28, 1870, at Metz, a venerable old fortress city on the Moselle River, the 62-year-old Emperor Napoleon III, aging, ill, and by now plagued by gallstones so severe that he couldn’t even ride in a carriage without experiencing excruciating pain, somehow managed to haul himself up into the saddle to say a few words to the Army of the Rhine. Since it was universally understood that in times of war a Bonaparte’s place was at the head of his troops, he had been obliged, in spite of his increasingly poor health, to take command of the French Army. Although he could boast a closet full of gold-braided uniforms and a host of gilded medals, the truth was that for all the martial trappings he so adored, this genuine heir of the great Napoleon could scarcely comprehend a field map, much less master the complexities of military strategy and tactics.

“Whatever May Be the Road We Take, We Shall Come across the Traces of Our Fathers”

Nevertheless, prisoner of his own honor and inflated reputation though he was, Napoleon III was determined, at least, to shoulder the responsibilities in this hour of crisis attendant to both his title and his famous name in the hopes of achieving another Solferino. His order of the day, issued later that evening, said it all: “Whatever may be the road we take beyond our frontiers, we shall come across the traces of our fathers. May we prove worthy of them.”

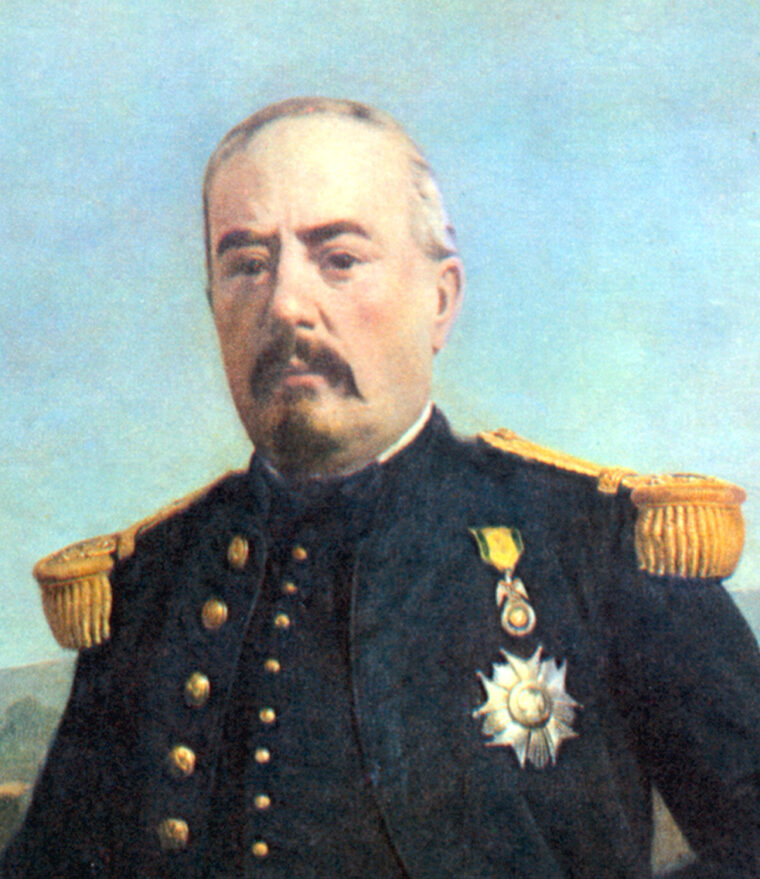

Metz, in the province of Lorraine, was just a short distance from Prussia. The massive French thrust across the border that the Prussians had been so sure was coming, was exactly what Napoleon III’s generals had in mind when they decided to marshal the entire French Army there and in the adjacent province of Alsace. After the Emperor, who had arrived at Metz to take personal command of the army, second in the chain of command was the famed Marshal Achille Bazaine, a battle-tested veteran of the Mexican Campaign. At Strasbourg, with the troops of the southeast sector, was another old soldier, Marshal Patrice MacMahon. A tough, flinty warhorse of Irish descent, MacMahon was the proud Commander of the Army of Alsace. A third Marshal of France, Canrobert, remained with the reserves in the rear at Châlons.

Once at Metz, Napoleon III quickly realized that the forces he had come to take command of were only about half their authorized strength. Worse still, rather than the uniformly crack troops he was expecting to see, many of the soldiers were of an entirely different caliber altogether. An ill-equipped, badly trained, undisciplined cohort, they gave every sign of having been scraped together at the last minute. These were the fruits of France’s criminally incompetent system of mobilization. Three weeks into their “mobilization” the French Army was still not ready. Precious days continued to pass. The original plan had counted heavily on the army’s ability to mount an enormous offensive that would overwhelm the Prussians before they had a chance to marshal their forces in strength. Instead, the opposite was happening. Any hope of surprising their adversary had now been lost, and every day that the French continued to dawdle the Prussians grew stronger and more confident. As August began, Napoleon III and his generals realized that they could wait no longer. Ready or not, they had to act.

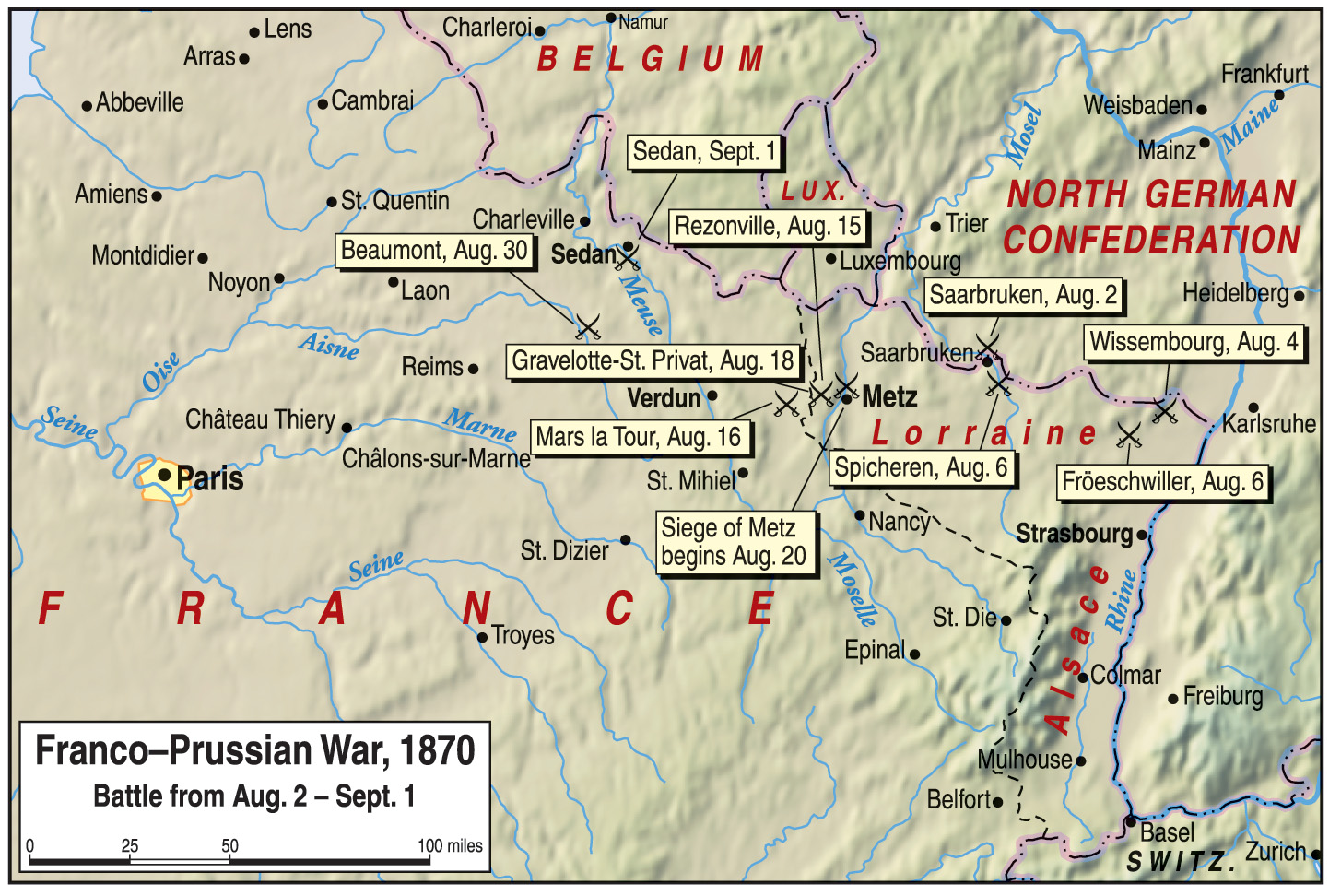

An Attack across the Border, on Saarbrucken

With both the editorial pages and the politicians in Paris beginning to show signs of impatience, the French High Command decided that it was essential to mollify public opinion by acquiring at least a modicum of Prussian blood on their bayonets as quickly as possible. Saarbrucken was a nondescript little town of dubious strategic importance, but it did have one thing going for it that made it enormously valuable to the French from a propagandist’s point of view: It was on the other side of the border in Prussian territory. On August 2, a disproportionately huge force of 60,000 men was sent marching across the frontier to take the town. The attack, which commenced early that morning, encountered surprisingly stiff resistance.

The single infantry regiment garrisoning the little town put up a good fight, holding off their numerically superior foe for several hours, until around 11 am, at which point their sensible commander prudently decided that an orderly withdrawal was probably their best option. This was done in almost textbook fashion, and within the hour the French were waving their colors triumphantly on the heights above the town, happily congratulating themselves on their victory. Rather than chase after the retreating Prussians, the French were content to simply jeer at them as they made good their escape.

Strangely, although they had technically captured the town, Saarbrucken’s complacent conquerors never actually set foot in it. For the better part of two days they just camped there on the hillside before striking their tents and heading for home. Nevertheless, the newspapers, the politicians, and the French people seemed all but ready to declare a national holiday when news of the great “victory” reached them. From a public relations viewpoint at least, this first “great” thrust into enemy territory had been a resounding success.

Once More into the Breach

Undoubtedly glad to be safely back across the border in Lorraine, Napoleon III, whose gallstones had plagued him so mercilessly that he had almost fainted out of the saddle toward the end of the action on the first day’s fighting, was probably secretly relieved that Field Marshal Bazaine and the generals surrounding him seemed content to spend the next two days patting themselves on the back; or perhaps it was simply that they were waiting for some sign from him. Either way, on August 4, the events that transpired in nearby Alsace must have made for an extremely rude awakening. That morning, the Prussian Third Army, commanded by no less than the royal diarist, Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm, began pouring over the French border in a flood of men and materiel. At a little past 8 am they made first contact with the enemy when they took on a small division of MacMahon’s command at Wissembourg.

In a way, it was Saarbrucken all over again, as a tiny, outnumbered French frontier garrison defended its position for several hours against an overwhelmingly superior enemy force before bowing to the inevitable. Unfortunately for the French, that was where the similarities ended, for what they effected at Wissembourg was not so much a tactical withdrawal as it was a headlong retreat. Having managed to hold the line until about 3 pm, what was left of the garrison’s complement, by now thoroughly decimated by the determined Prussian assault, simply broke and fled, rushing through the nearby vineyards in complete disorder. Their commanding officer, in a harbinger of things to come, had been blown to pieces by an exploding shell.

Just a few miles south at Fröeschwiller, Marshal MacMahon remained as cool as a cucumber. He had only recently moved the bulk of his command there from Strasbourg when news of Wissembourg reached him. Taking full advantage of the region’s topography, he deployed his men along a commanding position on Fröeschwiller Ridge. Considering the Prussians had outnumbered his men at Wissembourg by something like eight-to-one, the fact that they had managed to carry the day seemed hardly surprising. Supremely confident, MacMahon was so doubtful that the Prussians would dare to challenge his position on the ridge that he didn’t even think it necessary to dig defensive trenches. He was somewhat less sanguine on August 6, when in the early morning hours forward elements of the Prussian Third Army suddenly came into contact with his troops. Having literally stumbled into each other, the accidental encounter escalated quickly and ferociously, until by noon it had developed into a major battle.

Prussians Out for Blood

The Prussian attack on Fröeschwiller, which MacMahon was convinced would never happen, transformed a sleepy little corner of Alsace into an abattoir. This time, as the Prussian commanders launched wave after wave of men into the fray, they were met by resolute Frenchmen who fought back with furious courage, stubbornly refusing to submit. But it was not enough. The Prussians were also brave—and out for blood. Despite heavy losses, they continued to advance against the murderous fire being laid down by the French infantry with their chassepots. Neither the French soldier nor his rifle were found to be wanting, but the French artillery was.

It was at Fröeschwiller that the steel-cast breech-loaders made their terrible debut. The cannon that experts the world over had looked upon with skepticism and scorn during the many years of research and experimentation it took to produce them now announced to the world in thunderous tones that the “bronze age” was dead. Performing with a previously undreamed of range and rate of fire and a devastating accuracy that stunned both Frenchman and Prussian alike, the Krupp cannon made the suddenly old-fashioned muzzle-loading bronze field pieces of their adversaries look like something out of the Middle Ages by comparison. With unheard of precision, the Prussian batteries pinpointed Napoleon III’s cherished mitrailleuses, knocking them out of commission as if it were child’s play. Then they hurled shells down upon the French gunners, blasting them and their outmoded field pieces to smithereens. When that was done, they went after the piteously exposed troopers crowding the length of the ridge.

Defenseless French Infantrymen Looked Like “a Startled Swarm of Bees”

The result was an unholy slaughter. For several hours, as the Prussian shells rained down upon them, hammering their positions at will, the French continued to fight on, despite the appalling carnage that was erupting all around them. The Prussians, whose losses had been heavy that day, were beginning to realize that they needn’t sacrifice so many men in the future. They could simply hold their men back until their artillery had done its deadly work. Watching from a comfortable distance, a Prussian veteran would later recall that with the bursting of each shell, the defenseless French infantrymen looked “like a startled swarm of bees.” The pile of dying and dead was so thick that one couldn’t see the ground anymore, only a writhing mass of despoiled humanity roiling and thrashing about in agonized heaps.

In a final act of desperation, MacMahon resorted to the time-honored, last-ditch tactic of all commanders in extremis: He ordered his cavalry to charge. For 70 years the very mention of the word “cuirassiers” had been enough to make an infantryman quake. They galloped down from the ridge, breastplates and plumed helmets gleaming in the late afternoon sun, but for all their magnificent valor, their efforts amounted to little more than martyrdom. As horses and riders hurled themselves rank after rank into the teeth of the enemy, the famed cuirassiers were thwarted by a hail of bullets and hedgerows that impeded their progress. Once the momentum of their assault had stalled, they became worse than sitting ducks. Caught out in the open and helpless, they were shot out of their saddles with chilling efficiency by several well-positioned Prussian grenadiers. Finally, after eight hours of merciless shelling and driven beyond all human endurance, the French forces folded. Losing all semblance of unit cohesion, the wretched, utterly demoralized survivors abandoned the charnel house that was Fröeschwiller and ran for their lives. By 4:30 pm, MacMahon and what was left of the once proud Army of Alsace were in headlong, panicked retreat. Behind them, 11,000 dead and wounded, nearly half the army’s original strength, lay sprawled about the battlefield.

General Frossard’s Troops Greatly Outnumbered

On the same day that MacMahon watched helplessly as half his men were slaughtered around him, another proud soldier, General Frossard, commanding the 2nd Corps of the Army of the Rhine, watched his situation devolve into yet another ignominious defeat 40 miles to the northwest, at Spicheren. After returning to French soil after the attack on Saarbrucken, he too had taken up an excellent position on high ground. His troops, like those of MacMahon’s, had practically tripped over the enemy, in this case the Prussian First and Second Armies. Had Frossard only made use of the three divisions of reinforcements that were available to him less than 10 miles away, things might have been different. Spicheren was as close to a “traditional” battle as the French would see in the entire war. As it was, Frossard failed to realize how badly outnumbered he was until it was too late. By then the Prussians, at the cost of an enormous number of dead, were already advancing on his flank through the smoldering, shell-pocked landscape, forcing him to abandon his position on the Spicheren Heights.

As they fell back in wild retreat, Frossard’s troops barreled into the reinforcements coming toward them from the opposite direction. Soon they were all heading in the same direction, away from the Prussians, who by now had captured the heights. Only four days had passed since the first shots were fired at Saarbrucken, time enough for the world to be turned upside down. Now, as the world watched in stunned surprise, the mighty French Army fell back in confusion. They had been so sure of themselves. After August 6, they would never be sure of anything else again.

Incredibly, definitive news of the terrible events at Fröeschwiller and Spicheren did not reach Napoleon III until late in the day. At the very moment MacMahon’s and Frossard’s commands were being battered to bits, the Emperor was back at his headquarters in Metz, desperately trying to roust his troops out of their pastoral torpor. At long last, a concerted offensive thrust, an attack in force deep into Prussian territory, was on the table. The final flourishes were just being set down on paper when the ominous reports began to trickle in: MacMahon had been completely routed. Nobody even knew where Frossard was, only that he was in full flight. It was as if somebody had let the air out of a balloon. The much hoped for offensive died then and there on the table. It was more than just a question of being forced onto the defensive. Suddenly, all of France was in danger of being overrun. Thoroughly deflated, the generals in attendance reacted to the crisis by indulging themselves in a furious round of finger pointing. The impact of it all struck the Emperor like a bullet. Watching the situation dissolve around him, Napoleon III simply hung his head and retreated to the temporary safety of his tent, no doubt tortured by his ever roiling gallstones and the thought of what new horrors the sunrise would bring.

Disunity, Defeat, and Despair at Metz

The coming of dawn brought only greater disunity. As the ugly truth of their situation filtered down through the ranks, a crippling air of defeatism and despair permeated the atmosphere at Metz. While the Imperial General Staff bickered with the politicians back in Paris as to what to do next, more precious time was lost. With thoughts of defending the capital, Napoleon III had wanted to march the Army of the Rhine back to Paris, but was quickly advised that a return to the city under the cloud of so catastrophic a defeat would have dire consequences for the dynasty. Moreover, over the course of several days, and with excruciating delicacy, it was tactfully put to the Emperor that in light of the gravity of the situation, the subsequent conduct of the war might best be left to the professionals. It was suggested that Châlons, where what was left of the Imperial luster might aid in the raising of yet another army, would be a more prudent choice, and that assuming more of a figurehead type of role might better suit his obviously flagging health. For a Bonaparte and an emperor, it must have been a devastating rebuff, but he was anxious to do what was best for France and kept his private thoughts to himself. Exhausted, Napoleon III agreed to go.

As for the Army of the Rhine, the baton of command was passed, with equal parts haste and reluctance, to Marshal Bazaine. He had received orders from the Emperor himself to evacuate Metz and make for the old fortress city of Verdun before their line of retreat was completely cut off by the Prussians, whose Second Army was already ramming its way deep into the French countryside just south of Metz, coming between them and the capital. At Verdun, it was hoped that Bazaine might be able to “join hands” with MacMahon, who was thought to be somewhere in the area, the latter having stubbornly ignored a previous order to fall back on Metz in the aftermath of the unmitigated disaster at Fröeschwiller. Finally, on August 14—a full eight days after the dire events of August 6—Bazaine, reluctant to leave so well fortified a base, began moving the Army of the Rhine out of Metz.

Although he had doggedly committed himself to following the Emperor’s commands to the letter, nothing, it seemed, could induce Bazaine to move with anything so undignified as speed. Despite the fact that von Steinmetz and his Prussians were still coming on with a vengeance, following close on their heels, Bazaine conducted the withdrawal at a leisurely, almost slothful pace. Disorganized and chaotic, the columns that tramped their way along the crowded, dusty road to Verdun began to look more like a band of refugees than an army. Directly to the south, the Prussian Second Army, under the command of another of Wilhelm’s sons, Prince Friedrich-Karl, was moving parallel to them. Easily outpacing Bazaine, the Prussians raced ahead until, on August 15, they were able to swing round in a northern arc along the Metz-Verdun road, completely cutting off the French line of retreat, much as the Emperor had feared.

A Prussian Corps Takes on a Whole Army

Just about this time a corps of Prussians slammed against Bazaine’s army at Rezonville almost by happenstance. Not realizing they were taking on an entire army, the smaller Prussian corps quickly opened fire on the French encampment. The general melee that followed was a bloody, chaotic affair, punctuated by the acrid gray-blue wisps of gunpowder that hung in the air throughout the day, and by the Frenchmen’s stubborn addiction to hurling wave after wave of cavalry—the flower of the French Army—into the pitiless maw of artillery and rifle fire. For their part, the outnumbered Prussians fought tenaciously. The French could have used some of that dogged tenacity, for although they fought hard, in truth, something of the fight had already been taken out of them. The fact that a Prussian corps had managed to fight a whole army to a standoff bears testimony to that fact.

By dusk, both sides were again claiming the victory laurels, but the Prussians had succeeded in cutting off the road to Verdun. On August 17, Bazaine, who had never really wanted to leave the fortress at Metz to begin with, now sought to abandon the withdrawal to Verdun entirely and somehow get his command back to Metz, even as his putative sovereign was on a train rushing in the opposite direction toward Châlons.

What Napoleon III beheld when he reached Châlons must have set his already wretched gallstones on fire. The great military camp, once a shrine to Napoleonic glory, had been overrun by the retreating survivors of MacMahon’s shattered command. Trainload after trainload of traumatized, exhausted, desperate men had descended on the place, transforming the once glittering citadel into a dumping ground for worn out, disillusioned combatants. Their only thought, as they stumbled off the trains and careened about the grounds, was to help themselves to anything of value that wasn’t nailed down, vent their frustrations by smashing the rest and, generally speaking, drink themselves to death. These were the veterans of Fröeschwiller.

Fortunately, by the time the Emperor arrived, Marshal MacMahon was already on the scene. Somehow he managed to restore order and corral both his wayward charges and several battalions of reservists newly arrived from Paris (130,000 souls in all). These became the Army of Châlons. Military discipline, of a sort, was reinstated, but the ardor was gone.

The French Hold an Urgent Military Conference

On August 17, an urgent military conference was held in which the merits of a march on Paris to safeguard the capital were once again debated. One thing was certain: As Châlons was utterly indefensible, it would be suicide to remain there. They were still trying to decide what to do the next day when they received word that Bazaine was once again joined in battle with the Prussians—this time at Gravelotte.

The hostilities, which commenced around noon on the 18th, marked the first time the Prussians and the French engaged in a major, full-scale battle that had not occurred by accident. Gravelotte was deliberately planned by the Prussian Chief of Staff himself, Field Marshal von Moltke. Bazaine’s army was dug in along the wide, rolling plateau to the south of the city between Gravelotte and St. Privat, taking advantage of the natural defenses afforded them by the presence of a large ravine. Hoping for a decisive victory, the Prussians decided to meet them head on. With an almost fanatical zeal, the Prussian First Army flung itself at the French positions in a succession of fruitless assaults, only to be repeatedly beaten back by the determined defenders. As they hastened to engage their foe, the Prussians neglected to take full advantage of the overwhelming superiority of their artillery.

It was a pointless waste of men and a sobering lesson for the Prussians, who, unlike the French, would learn from their mistakes. By sundown, the ravine was chock-full of dead Prussians. An English war correspondent who was on the scene said it best: “The deep ravine … was a horrible pandemonium wherein seethed masses of German soldiery … writhing under the stings of the mitrailleuses.” The Prussian First Army, having lost twice as many men as the French, fell back in shock. The French had finally given the Prussians a first-rate drubbing. But once again, incredibly, no order was given to capitalize on their gains and pursue the enemy. Bazaine’s eternal caution again asserted itself, nullifying the valiant efforts of his men.

The Battle of Gravelotte Ends in Victory for Prussia

Thanks to Bazaine’s failure to seize his chance, the enemy was allowed to pull back unhampered. Before the night was over, the Prussians had recovered. In bitter fighting, their Second Army managed to wheel around and outflank the right wing of the French forces to the north of Gravelotte, forcing them to retire in confusion. Reinforcements might have saved the day; as it was, the French right wing had no choice but to cut and run all the way back to Metz. The following day, August 19, Bazaine himself withdrew to Metz, taking the rest of his army with him, ostensibly to rest and regroup. With that, 150,000 crack troops simply walled themselves up for the duration. No one was more surprised than von Moltke when he realized that the Battle of Gravelotte had ended in yet another victory for Prussia.

The next day, as a hard rain drenched Châlons, Napoleon III was conferring with Marshal MacMahon when they received word that the Prussians were on the march less than 25 miles away and heading directly at them. For once, the French did not dither. MacMahon and his army, with Napoleon III in tow, struck their tents in the teeming rain and cleared out as fast as they could. Châlons, the once gleaming trophy room of the Second Empire, was unceremoniously abandoned to its fate.

The Army of Châlons headed north to Rheims. For something like 72 hours, while the nation lay prostrate with a dagger at its throat, MacMahon and his increasingly vestigial Emperor huddled together with government ministers from Paris, trying to decide whether or not the time had come to fall back and prepare for a last stand defense of the capital. It was then that a message from Bazaine arrived from Metz. The message, which was already three days old, blithely explained that Bazaine was there resting his exhausted troops and that within two to three days he intended to break out, make his way north, and carry on the fight. To MacMahon, this indicated that Bazaine was already on his way northward, heading toward him. Expecting to link up with Bazaine, he immediately gave the order to march. The Army of Châlons would join forces with the Army of the Rhine, and like a latter-day Joan of Arc, save the sacred soil of France from its foreign invaders.

MacMahon’s Command Looks for Bazaine and Glory

On the 23rd, MacMahon’s command set out northeast toward the Meuse River, looking for Bazaine and glory. They found neither. Bazaine was still at Metz. Not only had he not effected a breakout, but he was now even more disinclined than ever to leave the security of his fortress. It was a colossal failure of intelligence that would lead to disaster. MacMahon and his equally unsuspecting Emperor were about to enter the deadfall.

As for the Prussians, there was no such confusion of purpose in their camp. Under orders from von Moltke, Prince Friedrich-Karl’s Prussian First Army promptly surrounded Metz, bottling up Bazaine’s forces once and for all. Now he couldn’t escape even if he had wanted to. When a Uhlan patrol reached Châlons and found it abandoned, Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm’s Third Army, along with the newly minted Army of the Meuse, was immediately ordered to march on Paris. They expected to capture the city after first taking on MacMahon in a climactic showdown. The very idea that the French capital lay before them virtually undefended never entered their heads. Like the rest of the world, in spite of their stunning record of victories in the campaign up to that point, they were still a little in awe of the mighty French reputation and still scarcely able to take in the enormity of what they had already achieved. Never in their wildest dreams could they have imagined that MacMahon would be so reckless as to leave Paris to providence and risk getting caught out in the open by two formidable armies in an effort to “save” Bazaine. But, spurred on by the Parisian bureaucrats with which he was conferring, that is exactly what MacMahon did.

The Prussians might never have believed it if one of their spies in Paris had not gotten hold of a Parisian daily newspaper, Le Temps. It was all there in black and white, a breathless account reporting that MacMahon’s forces were gallantly making their way to the northeast to find Bazaine, marshal the French forces, and strike a great blow against the enemy. When a copy of the newspaper reached von Moltke late in the evening of the 25th, he quickly ordered his two armies marching on Paris to veer north instead to find and destroy MacMahon.

Their quarry would not prove hard to find. In the midst of a torrential downpour, a hungry, disillusioned army of already beaten men was tramping its way through an ocean of mud on their way to the Meuse and what, they were convinced, would be their deaths. Military discipline was dissolving again. Breaking formation at will, they were more like brigands than soldiers as they looted and pillaged farms.

The Ill-Fated March to the Meuse

On the 26th, MacMahon’s forces spotted Uhlan scouting patrols in the vicinity of the Argonne Forest. At long last, the Emperor was able to convince MacMahon of the dire nature of their situation. Stunned to see Prussian blue instead of any hint of Bazaine’s presence in the area, MacMahon realized he must still be at Metz. Worse still, with three enormous Prussian armies converging on him from three directions, his command was in grave danger of being surrounded and annihilated. He halted the march and cabled the politicos in the capital, informing them of his decision to fall back on Paris, but the Council of Ministers, which had succeeded in subsuming much of their increasingly irrelevant Emperor’s power, would have none of it. Stubbornly, stupidly, they ordered MacMahon to continue his march and “relieve Bazaine.” If ever in his career MacMahon had received an order that should have been disobeyed, this was it, but by now the old soldier was nearly as demoralized as his men. Despite the pleas of his ailing Emperor, MacMahon resumed his ill-fated march to the Meuse.

On the 30th, MacMahon’s forces reached the Meuse and began crossing the river. The northern sector of his command managed to make the crossing relatively unhampered, but the southernmost body of his army, the 5th Corps under General de Failly, having already encountered Prussian troops the previous evening, were caught out in the open in the early hours of the morning on the rolling hills upon which they had encamped for the night. There, just outside the village of Beaumont, the Prussians caught up with them a second time and began raining shells upon the exhausted, disoriented men. Although some bravely held their ground, most simply ran for their lives in every direction in a desperate attempt to escape the relentless hail of Kruppstahl.

Officers begged them to stand and fight. An 11th-hour cavalry charge was thrown against the Prussian batteries in a useless act of sacrifice. As the panic-stricken soldiers rushed the bridges, clawing and climbing over each other in a frantic effort to get across, hundreds of men fell into the water while dozens more jumped in a futile attempt to swim for it. Laden down by their packs and greatcoats, nearly all of them drowned. In all, more than 7,000 Frenchmen died in those terrible hours at Beaumont. With the Prussians in hot pursuit, and with almost nowhere else to go, MacMahon ordered his traumatized soldiers to make for the closest town, a tiny nondescript place seven miles from the Belgian border that had scarcely changed since its medieval heyday. Its name was Sedan.

“We Are in a Chamber Pot and We Are Going To Be Shat Upon”

Although the sight of the little fortress-town’s 17th-century walls did little to rally his heart, Marshal MacMahon thought that the high ground at the northern edge of the town was a “position magnifique” from which to mount a defense. There were others on hand, however, who could only shake their heads in disgust. Sitting ashen-faced by the light of a campfire that night, General Auguste Ducrot, who had somehow managed to survive the meatgrinder at Fröeschwiller, grimly predicted the fate he knew was in store for all of them. “We are in a chamber pot,” he said wearily, “and we are going to be shat upon.” By the evening of the 31st, the Prussians were already moving to encircle the town. “Now,” said a jubilant Field Marshal von Moltke, “we have them in a mousetrap.” He was right.

On the morning of September 1, an amazing procession made its way up to the top of a hill just above the village of Frenois. Helped along by a glittering escort of Imperial Life Guards, King Wilhelm I led a gilded hodgepodge of assorted officers and aristocrats from the various German kingdoms and several foreign military observers, including General Philip Sheridan of the United States, to what would prove to be the perfect location from which to witness the death of the old order in Europe. Squinting through Wilhelm’s telescope or the field glasses obligingly provided by aides, they could clearly see the swirling waters of the Meuse a short way off, and beside it, the tiny town in which MacMahon, his tattered troops, and (unbeknownst to the Prussians) the Emperor of the French lay cornered. They were so close that they could even make out the people gliding up and down the streets. The town was surrounded by undulating valleys and quaint little farmhouses. At its northern edge loomed the pine forest of the Ardennes. It was all too beautiful.

The World Turned Upside Down

Below the august group on the hill above Frenois, the future battlefield spread out before them in the shape of a triangle, its base facing Wilhelm and his guests. Sedan itself lay in the center of the base, with the villages of Floing and Bazeilles, respectively, occupying the western and eastern corners of the base. A road running northeast of Floing formed the left side of the triangle, while another running northwest along the valley of Givonne formed the right. At the apex of the triangle, where the two roads came together, lay Olly Farm. The hilly, wooded landscape located within the triangle sloped downward toward the base. There in the valley of the Meuse, the French Army peered over the walls of Sedan into the early dawn, watching their prospects disintegrate by the hour.

Had they moved with purposeful action they might yet have avoided the encirclement. As it was, they were on the verge of being completely surrounded. In this moment of peril, Napoleon III, perhaps sensing that his empire’s end and the hour of his own death were near, seems to have rallied. The night before, as he shuffled painfully along the town’s ancient cobblestones, lost in contemplation beneath a canopy of stars, MacMahon begged him to try and save himself while there was still time. “I have decided not to separate my lot from that of the army,” he said softly. In the end, he was a Bonaparte after all. He resolved that if he was to die, history would record that he died well.

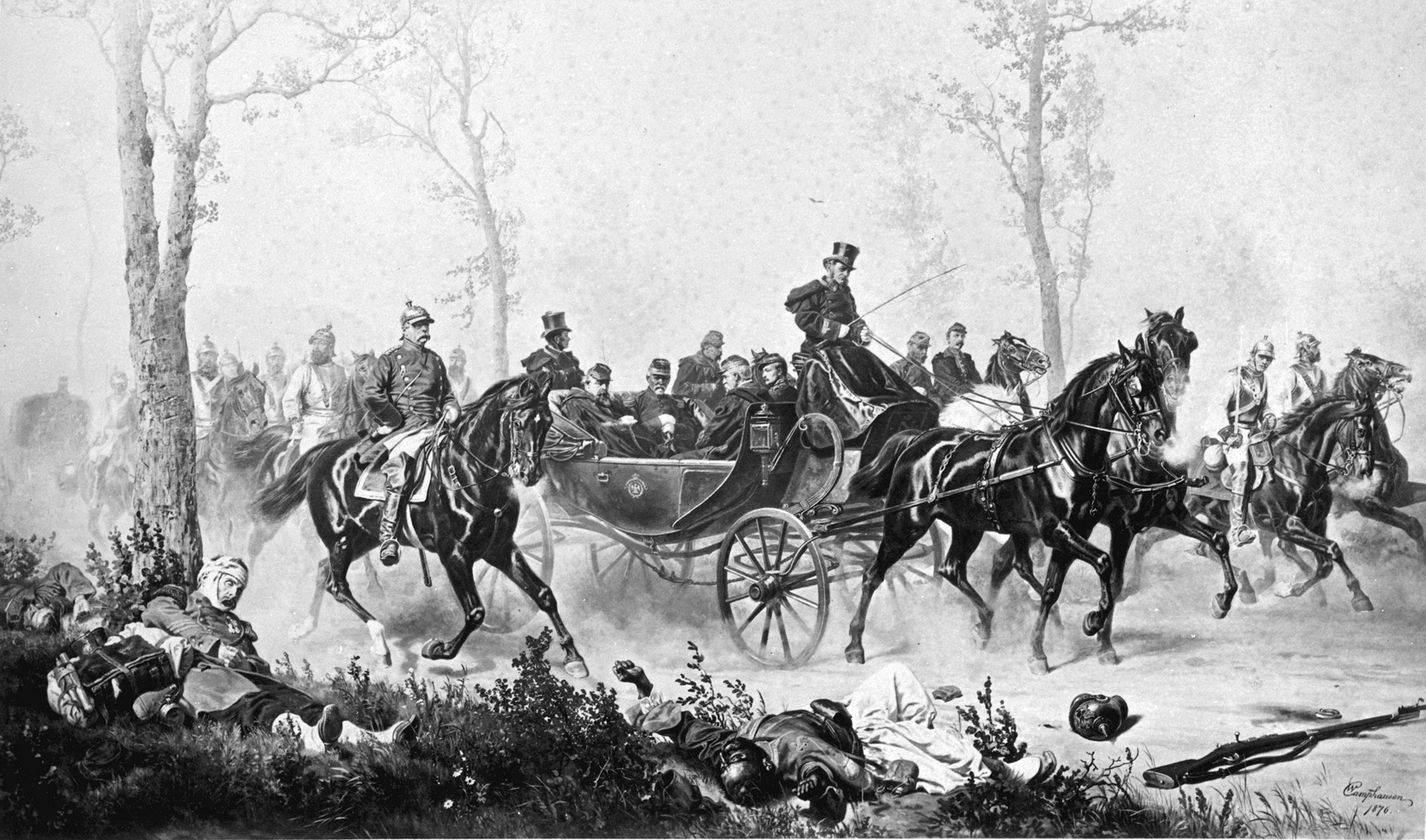

Early that morning, the Prussian steamroller moved to pounce on the defensive positions hastily thrown up by the French around Bazeilles, torching every farmhouse in their path. As they did, Napoleon III, medal bedecked and clad in his finest dress uniform, rode out of Sedan with his retinue and headed straight for the sound of the guns in search of honorable death. Marshal MacMahon must have had the same idea, for as the Emperor galloped toward Bazeilles, he was greeted by the sight of the old marshal being carried back up the road to Sedan on a litter, a shell fragment lodged in his leg. Unable to remain in command for the time being, MacMahon was barely on the surgeon’s table when his subordinates began to squabble with each other over who was entitled to take command. All the while their Emperor was searching the battlefield for an honorable way to die.

Napoleon III Waits for Death, but Remains Unscathed

While his staff, at the Emperor’s urging, took shelter behind a wall, Napoleon III, in the company of three officers, galloped to the top of an exposed hill. Leaving the men behind him, he rode on farther still and then halted, waiting for death. Shells and gunfire erupted around him and at one point his orderly, who was a little farther behind him, was literally blasted out of his saddle. But each time, as the smoke cleared, the Emperor remained unscathed. On he rode while shells burst all around him, up along the ridge of the valley of Givonne.

He then dismounted and briefly stood shoulder to shoulder with the men of a mitrailleuse battery, turning the crank that discharged the weapon, just another soldier of France. His eyes grew red and moist as he shared the ordeal of his beloved soldiers and his ears rang with the cries of the wounded. For nearly five hours, despite the agonizing pain of his gallstones (one of which was diagnosed as being the size of a pigeon’s egg), Napoleon III remained in harm’s way, waiting for the release of death. But though shells fell like rain all around him, the absolution of the battlefield was denied him. He returned to Sedan. There, at around 1 pm, several of his generals advised a breakout that would effectively have sacrificed the lives of countless soldiers on the off chance that Napoleon III and most of the senior officers might make good their escape. The Emperor categorically refused to hear of it.

Shortly thereafter it became a moot point. About an hour earlier, just before noon, the Prussians had linked up at the triangle’s tip, at Olly Farm. Nearly the whole of the French line had crumbled under the ceaseless shelling of Prussian cannon. In one final desperate action just above Floing, the redoubtable General Ducrot ordered his cavalry to charge. Down the hill they galloped, with swords flashing, straight into the blazing Prussian fire. As the survivors of that magnificently futile charge returned, Ducrot inquired of their nonplussed commander, General de Gallifet, whether his men had it in them to try again. “As often as you like, mon General,” he answered, “so long as there is one of us left.”

The French Are Completely Surrounded

At least twice more, the finest cavalry in the world proved that if they could not win, they could at least show the world that they were not afraid to die trying. Peering through his telescope at the top of his hillside observation post, Wilhelm’s eyes stung at the sight, as he murmured to himself in the language of his enemy, “Ah, les brave gens.” By 3 pm, what was left of the French infantry had raced pell-mell back into the town, a bloodied, terrified mob. The French were now completely surrounded.

The next step, the merciless bombardment of the town, went on for hours, killing soldier and civilian alike, blasting the roofs off buildings, and setting whole sections of Sedan afire. Unable to find honorable death in battle as he would have wanted, Napoleon III, anxious to spare the lives of the many civilians trapped in the town and over the furious protests of his officers, ordered the raising of the white flag over Sedan. At one point it was hauled down and the shelling continued until the Emperor finally declared that “it is absolutely necessary to stop the firing.”

The white flag was raised again and a little later a delegation was sent to Wilhelm with a note from the Emperor, who decided to bear full responsibility for the capitulation. “Monsieur mon frere,” it read, “Having failed to meet death at the head of my troops, nothing more remains for me but to surrender my sword into your Majesty’s hands.” Bismarck, who was on hand, would not allow the two to meet face to face, lest as one sovereign to another Napoleon III might extract some favorable concessions from the soft-hearted Wilhelm. The Prussian terms, Bismarck said, were simple. Nothing short of the complete surrender of the whole French Army would suffice for hostilities to be considered closed. The French were over a barrel and they knew it. The terms, humiliating as they were, were accepted. At that point, Napoleon III was allowed to meet with Wilhelm.

“I Congratulate You on Your Army…”

It was an awkward meeting. “I congratulate you on your army, above all on your artillery,” a rumpled, ravaged Napoleon III said to the resplendently uniformed Wilhelm. “My own was so … shabby.” The man who would shortly be crowned the Kaiser of a unified German Reich looked away in embarrassment. Napoleon III was taken into custody and led to a waiting carriage by his Prussian captors. There began a brief period of confinement, followed by three years of a sad exile in England, before his gallstones would finally succeed where the Prussian shelling had not.

As for France herself, the bleeding did not stop at Sedan. A violent insurrection took hold of Paris. The victorious, increasingly arrogant Prussians demanded that the French provinces of Alsace and Lorraine be ceded to them. When the French balked, the city of Paris was placed under siege for a time, surrounded by a ring of Prussian artillery. Reduced to eating dogs, cats, rats, and nearly all of the animals in the Paris Zoo, the French finally gave in and the Prussians went home. Emerging from this chaos, the French Third Republic was born; Imperial France was finished forever. Bismarck had been right about that. As he watched the tragic figure of the once grand Napoleon III being led away, he was heard to remark solemnly, “There goes a dynasty on the way out.”

My German family emigrated to the US after this war. The reputation of a Prussian led country did not appeal to them and they correctly saw that there would be more war to come. My South German grandfather married a French woman some time after arriving in the US. She had also seen that Europe had an unpleasant future in store for those who remained.