By William E. Welsh

The crown of Spain and the wealthy banking families of Genoa had a symbiotic relationship during the Renaissance. King Philip III of Spain needed the financial clout of Genoese bankers to raise, supply, and pay Spanish and Italian troops serving in Hapsburg Spain’s Army of Flanders that had been fighting the Dutch since 1568.

King Philip was the Duke of Milan and also sovereign prince of the Low Countries and formerly Burgundian dominions, such as Franche-Comte, in eastern France. Although the Republic of Genoa was not ruled by the Spanish crown, it enjoyed the benefits of a protected state. Genoa’s wealth was derived from the goods it channeled from the Levant and Far East through its ports. Merchant ships from Constantinople and Cairo offloaded goods in Genoa that were then transferred to European merchant ships that carried them to northern Europe.

The Spanish crown neutralized French-backed conspiracies against Genoa and supported the ruling noble family in suppressing opposing factions within the city. In return, Spain had free access to the ports of Liguria, as well as the right to march troops arriving in Genoa from Spain to Milan.

From Milan the Spanish armies marched north through Savoy, Franche-Comte, Lorraine, and Luxembourg to Flanders. This was safer than transpoing the soldiers by ship where they might be intercepted and sunk by the English or Dutch navies. Ambrogio Spinola, the son of a prominent Genoese family of financiers, signed a contract with Philip III in 1602 to fund and raise 8,000 Spanish and Italian infantrymen for service in Flanders.

An ambitious sort, Ambrogio had succeeded marvelously as the head of his family banking business by shrewdly diversifying it, but he had no desire to remain simply a banker. He wanted to make a name for himself as a successful military commander so that his family had as much renown as the rival house of Doria in Genoa that had become famous because of the military achievements of Admiral Andrea Doria.

Spinola boasted to Philip III and his prime minster Francisco de Sandoval y Rojas, the Duke of Lerma, at the time of the contract that he could complete the siege of the Dutch the port of Ostend, which was in its second year, within one year of arriving in Flanders. But he said this would only be possible if they allowed him to fund the siege with his own money, so that the troops were paid and did not mutiny, and if they gave him sole command of the forces assigned to capture it.

Eager to capture Ostend, they agreed to his terms. Spinola arrived in Flanders with his troops, the majority of which were Italians eager to serve in the renowned Spanish army, in early 1602. Upon his arrival, he met with Archduke Albert, who served as the governor-general of the Spanish Netherlands.

Albert had besieged Ostend with 20,000 Spanish troops in July 1601. The garrison, which numbered 3,500 Dutch, was commanded by English captain Horace de Vere. Maurice of Nassau, the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, the commander of the Dutch army, reinforced the garrison by sea with an additional 3,500 troops. Albert, who was serving as the captain-general of the Army of Flanders, as well as the sovereign prince, had no knack for siegecraft.

Spinola returned to Genoa almost immediately to bring more troops, and he returned via the Spanish road with 8,700 more Italian troops. Spinola took charge of the Spanish forces besieging Ostend on September 29, 1603. De Vere had transferred out by that time and was replaced by Frederick van Dorp.

Spinola put his gifted Italian engineers to work mining Ostend’s defenses. Spinola had a gift for uncovering the weak points in a defensive position. He preferred aggressive assaults against enemy defenses during a siege over a methodical reduction of the enemy’s defenses. His disciplined Spanish troops successfully captured the port-city’s strongpoints in a series of bloody assaults. True to his word, Spinola forced the garrison’s capitulation in September 20, 1604, in less than a year’s time. In reward for his victory, Spinola was made a Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, a Catholic order of chivalry founded in the 15th century.

But the triumph over the Dutch garrison victory at Ostend was a pyrrhic victory. The Spanish had lost 40,000 troops capturing the port over the course of three years, it was in complete ruins, and the Dutch had made gains elsewhere.

Albert believed strongly in Spinola. He urged Philip III to appoint Spinola as the new captain-general of the Army of Flanders, but the Spanish king had certain misgivings about Spinola.

Spinola traveled to Madrid in 1605 to meet with Philip III. The Spanish king wanted Spinola to lead 10,000 troops in a siege of Sluis, while another Spanish commander invaded the United Provinces with the main army of 22,000 troops.

Spinola did not like the plan, though, and he threatened to quit and return to his banking business in Genoa. At the time the Spanish crown was on the verge of bankruptcy, and the fact that Spinola could raise an additional five million gold florins to help finance the war effort against the Dutch was the deciding factor in Philip III appointing him as captain-general.

Meanwhile, Spinola’s nemesis Maurice of Nassau had made great defensive strides. He fortified embankments and islands of the mouth of the Rhine delta in the United Provinces and constructed a chain of blockhouses on the west bank of the Ijssel River to thwart an invasion from the east by the Spanish army.

Spinola advanced north through the Hapsburg territory of Julich-Cleves-Berg and recovered Rheinberg in 1606, which had been lost to the Dutch in 1601. He continued north invading Overijssel, one of the eastern provinces of the Dutch Republic, but could not penetrate the Dutch defenses along the Ijssel. Spinola had succeeded in capturing six Dutch towns and cities that year despite the best efforts of Maurice to defend them. Unfortunately, 4,000 of Spinola’s troops mutinied for lack of pay When Philip III and Duke of Lerma, learned that Spanish troops in Flanders were once again mutinying, they gave serious thought to a ceasefire with the Dutch. The Dutch Republic had been growing in military strength steadily since 1597. In that time its army had doubled in size and the prosperous Dutch had quintupled their spending on fortifications.

Spanish and Dutch ministers began preliminary talks that year about a ceasefire, but it would not be until April 1609 that they entered into a longterm truce. That month representatives of both sides met in Antwerp and signed what became known as the Twelve Years’ Truce. With the Spanish crown still unable to pay its troops in Flanders, Spinola poured all of his wealth into paying them in order to maintain a powerful army in the region.

Philip III instructed Spinola to invade the Protestant-controlled Lower Palitinate in the western part of the Holy Roman Empire in 1620 in an effort to relieve pressure on the Austrian Hapsburgs. The Thirty Years War pitting German Catholics and Protestants against each other had erupted in Bohemia two years earlier. In autumn 1620 Spinola marched 20,000 Spanish troops into the region and forced the capitulation of its principal cities and some of the fortresses on the Upper Rhine. Bolstered by English troops, though, the Protestant garrisons of Frankenthal, Heidelberg, and Mannheim held out.

The truce expired in April 1621 and Spinola again led the Spanish field army in Flanders against the Dutch forces. The previous month, Philip IV had ascended the throne. His new prime minister, Gaspar de Guzman, the Duke of Olivares, was jealous of Spinola’s fame. In July 1621, Archduke Albert also died, and his wife, Infanta Isabella, became the sovereign ruler of the Spanish Netherlands.

As war spread throughout Europe, Spinola undertook operations to protect the Army of Flanders supply lines. He played a pivotal role in forcing the surrender of the Dutch garrison at Julich in February 1622, which posed a threat to movement on the northern terminus of the Spanish Road.

Spinola received orders from Madrid in spring 1624 to capture the Dutch-held citadel of Bergen op Zoom that summer. The fortress anchored the Dutch salient south of the Rhine, and to drive the Dutch from it would perhaps thwart the naval blockade of the Flemish port of Antwerp to the south.

Unfortunately for Spinola, two Protestant commanders, Ernst von Mansfeld and Christian of Brunswick, who previously led Protestant armies of the Elector Palatine Frederick V, had been dismissed from Palatine service. They allied themselves with the Dutch Republic and marched to the assistance of Maurice of Nassau. The added pressure by the Protestant reinforcements forced Spinola to raise the siege of Bergen op Zoom in October 1622 after just three months.

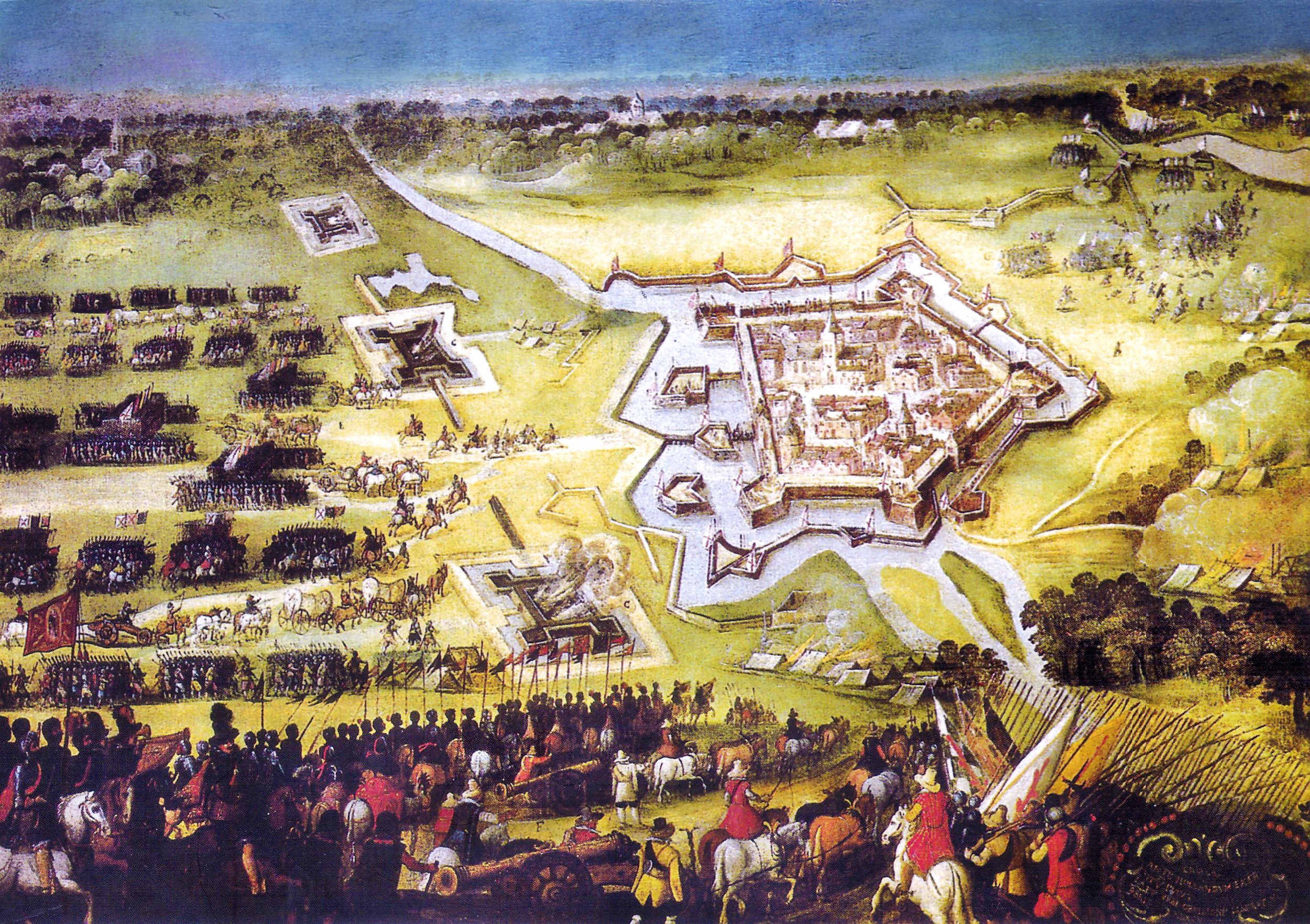

Stung by the defeat, he looked for a way to redeem himself. That opportunity came when Philip IV ordered him to capture Dutch-held Breda in Brabant, a region that was part of the Hapsburg Netherlands. Spinola faced a major challenge in reducing Breda and forcing its surrender because the Italianesque design had extensive water obstacles. A high earthen embankment behind a wide canal fed by the Mark River ringed the fort. The trace Italienne fortress boasted 15 bastions and each of its four gates were fortified as well. Olivares, who had advised Philip IV to order the siege, secretly hoped Spinola would fail.

At the time, the Army of Flanders numbered 70,000 troops, but two-thirds of that number garrisoned strongpoints throughout Flanders and adjacent Hapsburg dominions. Spinola took with him 23,000 Spanish troops to invest the 9,000 Dutch troops defending Breda. Rather than setting his infantry, engineers, and laborers to work digging a continuous line of siege trenches around the fortress, Spinola followed the method used by his predecessors in Flanders, the dukes of Alva and Parma, and established a ring of small forts and redoubts around the city. He also broke dikes to flood low-lying ground beyond his ring of forts to make it difficult for a Dutch relief army to attack them.

The Genoan also had his troops construct raised batteries for his artillery so that he could get maximum results from his guns. He also had his men construct barricades near the gates so that only a modest number of Spanish infantrymen were needed to contain any counterattacks. This freed up Spinola’s light infantry and cavalry to protect his rear and repulse attempts by the Dutch to relieve the garrison.

The siege formally began in August 1624. Mansfeld, who had 12,000 troops, attempted five times over the course of the 10-month siege to relieve Breda. Spinola’s forces repulsed every attempt.

While the siege was in progress, Maurice of Nassau died on April 25. Frederick Henry, Maurice’s younger brother, became stadtholder following his brother’s death and took command of the Dutch army. The new Dutch commander made one last attempt to fight his way through Spinola’s defenses in May, but it failed as well. Justin of Nassau, Breda’s governor, surrendered with honors in June. Only 3,500 Dutch soldiers had survived the brutal siege. In capturing Breda, Spinola felt he had avenged his humiliation at Bergen op Zoom.

The successful capture of Breda served as the climax of Spinola’s career. By that time, he was bankrupt and Philip IV and Olivares did not appreciate his achievements in Flanders. Facing criticism for allowing the Dutch to make minor gains, the 60-year-old veteran commander returned to Genoa in 1629 where he continued to command Spanish forces in a war over who would rule the Duchy of Mantua. His health deteriorated rapidly, however, and he died during the siege of Casale Monferrato in September 1630.

Spinola stands as one of the great commanders of the early 17th century. He possessed that special knack for being able to spot an opponent’s weaknesses and move quickly to exploit them. He was brilliant, daring, and highly competent, although he did not introduce any innovative tactics. His grit and determination, coupled with his willingness to invest his own fortune on behalf of Catholic Spain, revived Spanish fortunes in the Eighty Years’ War.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments