By William E. Welsh

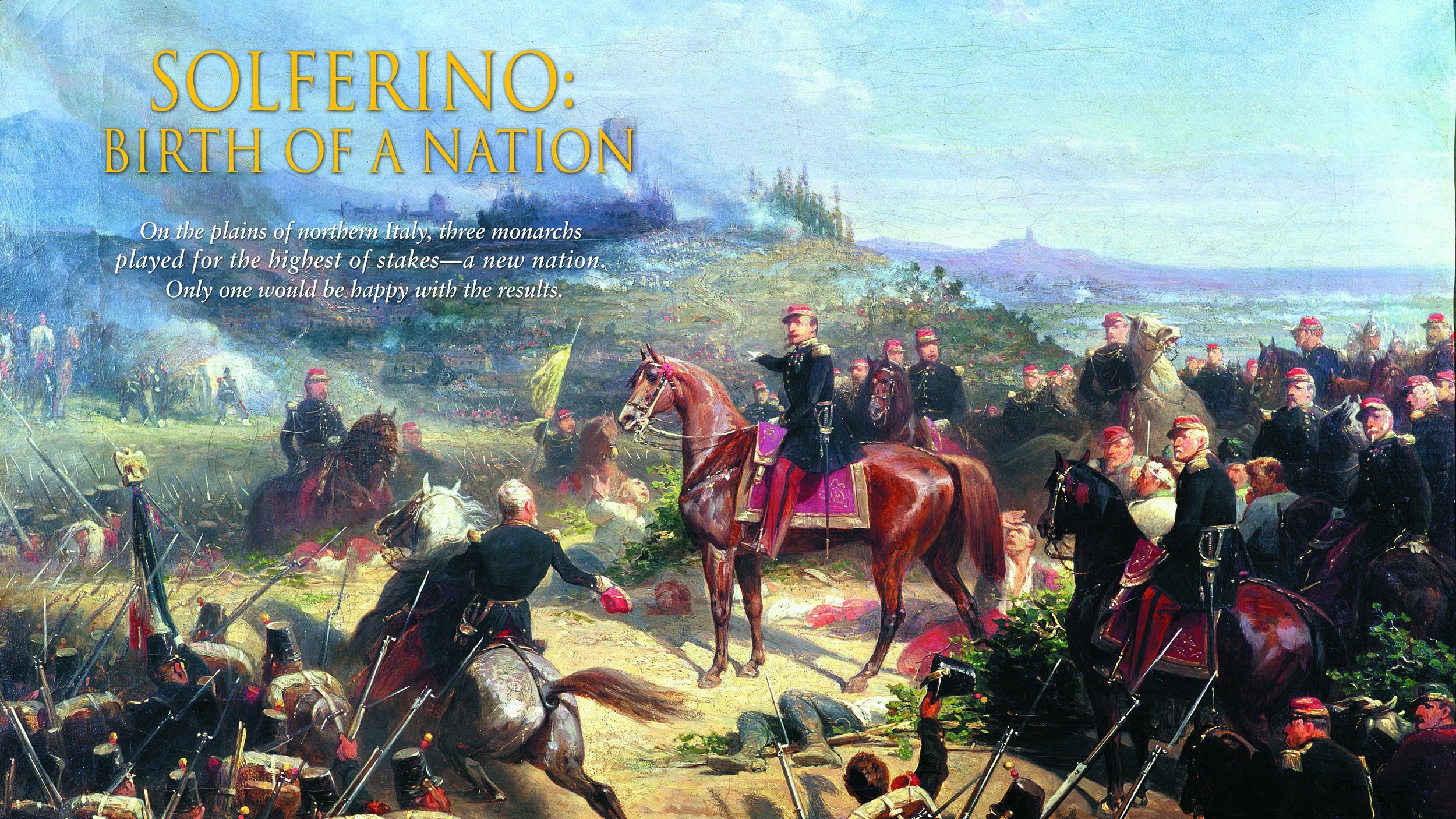

Duke Henry the Lion, the ruler of Saxony and Bavaria, seethed with rage. The pagan Wends had rebelled once more against their Saxon overlords. Led by a warlord named Pribyslav, they had launched a lightning raid in February 1162 against the Saxon frontier town of Mecklenburg. They not only had butchered the Christian residents but had also burned all of the buildings to the ground.

Henry gathered all available forces for a counterstrike. He called on his loyal vassals, Count Guncelin of Schwerin, Count Christian of Oldenburg, Danish King Valdemar, and Margrave Albert of Brandenburg, to assist him. Over the course of many months they pursued Wendish war bands through forest and swamps, inflicting losses on them and destroying their villages.

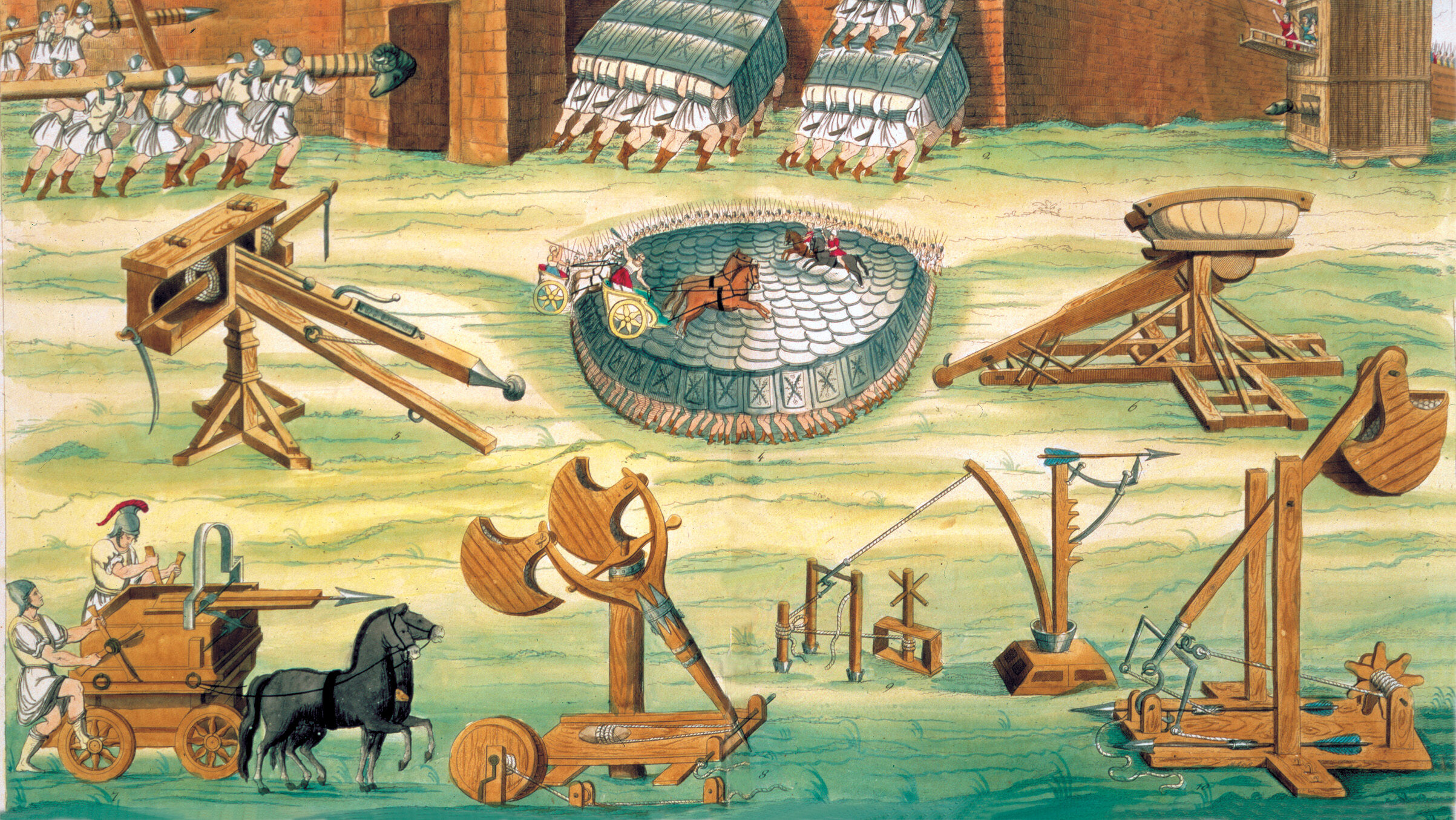

The campaign culminated the following year with the siege of the stronghold of Werle. The garrison commander had only a small force of Wends with which to defend the wooden fort. Henry’s pioneers built a battering ram and a siege tower, and he detailed a portion of his forces to guard against a relief attack by Pribyslav.

Henry had developed a superb knowledge of siege warfare from campaigning with Emperor Frederick Barbarosa against rebellious Italian city-states such as Crema, Milan, and Tortona. While his battering ram hammered against the main gate, the Saxons rolled the siege tower up to the wall. The tower dwarfed the town walls, and archers and crossbowmen atop the siege tower rained sheets of arrows down onto the defenders. Having lost many of their men to the missile fire, the defenders capitulated before the Saxon battering ram smashed through the gates.

The siege of Werle demonstrated Henry the Lion’s prowess as a warrior. Over the course of more than three decades of continual fighting, he would amass fame and reputation nearly as great as the emperor himself. For that reason, Barbarosa both feared and respected him.

By the mid-12th century, the Ottonian and Salian kings of Germany had successfully founded the confederated Kingdom of Germany. Unlike the hereditary French monarchy, German princes elected their kings.

The early 12th century was a tumultuous time in Germany. Civil war raged between the House of Welf, initially based in Bavaria and later in Saxony as well, and the Hohenstaufen House of Swabia. During his reign in the early 12th century, Hohenstaufen King Conrad III made a drastic bid to reduce the power of his principal rival in the kingdom, Henry X “The Proud,” the Welf duke of Saxony and Bavaria. He requested that Henry relinquish one of his duchies; when Henry refused to give up either, Conrad took then both from him. Conrad gave Saxony to Ascanian nobleman Albert the Bear, the Margrave of Brandenburg, and Bavaria he gave to Duke Leopold “The Generous” of Austria.

The disenfranchised former duke Henry and his younger brother, Welf VI, went to war against Conrad. Henry the Proud died suddenly at the age of 31 in 1139, but Welf VI stepped forward to lead the rebellion. The Welf army ravaged Hohenstaufen lands, but they were decisively defeated at Weinsberg Castle in the County of Wurttemberg in December 1140.

Eleven years earlier, in 1129, Henry the Proud’s wife, the wealthy Saxon heiress and daughter of former Emperor Lothair II, Gertrude of Supplingenburg, had given birth to their only child, who was given his father’s name.

Following the death of his father, young Henry (the future Henry the Lion) was considered the heir-apparent of Saxony and protected by his mother, as well as his grandmother, the former empress Richenza of Northeim. As a Welf noble, young Henry enjoyed widespread support among the princes residing in Saxony. Following Henry the Proud’s death, these princes drove Albert the Bear out of Saxony, for they believed the duchy belonged to the young Henry. Fearing for his life, Albert sought the protection of Conrad’s royal court.

After Welf VI surrendered at Weinsberg Castle in 1140, Conrad decided that it made more sense to return Saxony to young Henry than to try to re-install Albert by force as its ruler. He therefore granted it to the 13-year-old son of the deceased Henry the Proud in 1142. The young Welf aristocrat thus became Duke Henry III of Saxony.

Conrad, however, purposely declined to give Henry III the Duchy of Bavaria upon Leopold’s death in 1141. Instead, the German king bestowed Bavaria upon his half-brother, Henry II Jasomirgott, of the Austrian House of Babenberg.

The young Saxon duke chafed at the perceived affront. Because of his contempt for Conrad, Henry declined to accompany him on the Second Crusade to the Holy Land in 1147. Instead, he decided to campaign against the pagan West Slavs.

Henry longed to conquer lands from the pagan West Slavs who inhabited the territory between the Elbe and Oder rivers. These tribes, known collectively as the Wends, included the Wagrians, Obotrites, Polabians, Warnabians, Rugians, and Liutizians. The Ottonian and Salian German kings had established some control over the Wends in the 10th century when they established a series of marches—militarized borderlands and buffer zones—along the Wendish frontier. The Lusatian March was the southernmost of these three marches, the Northern March was actually the middle march, and the Billung March was the northernmost. However, an uprising by the Wends in 983 reversed most of the Saxon gains within the marches.

Duke Henry III sought to expand his realms into the Billung March, but he and his fellow crusaders faced a formidable opponent on the eve of this “Wendish Crusade.” Nyklot, the chieftain of the Obotrites, had assembled enough warriors to conduct effective hit-and-turn raids against the Saxons. The Obotrite chieftain was a clever, resourceful, and quick-thinking opponent.

At the beginning of Henry’s rule, he had divided the conquered Wendish lands adjoining Saxony with the help of one of his principal vassals, Count Adolph II Holstein and Schauenberg. Henry took control of the Polabian lands and the region’s capital of Ratzeburg. To the north, Adolf assumed rule over the Wagrian territory, including the town of Sigberg, as well as the strategically located port of Lubeck, which the count had founded in 1143.

In the years leading up to the Wendish Crusade, Adolf had entered into an alliance with chieftain Nyklot of the Obotrites. During the 1140s, he had encouraged Christians from Holland, Frisia, and northern Saxony to settle in the Billung March. To protect themselves, the settlers constructed watch towers, blockhouses, and palisaded forts.

The Wendish Crusade began in 1147 when Pope Eugenius III issued a papal bull against the Wends. The Papal decree had strict rules regarding the taking of tribute and the making of any truces with the Wends that allowed them to remain pagan. Those who did so risked excommunication.

Henry and Albert the Bear would each lead a separate column against the Wends living in the Billung March. In the spirit of cooperation against a common foe, Henry set aside any animosity he might have held towards Albert the Bear in regard to his brief rule of Saxony.

The northern Germans would be assisted in the crusade by the Danes. The Danes wanted revenge against the Slavic Wendish pirates and slavers, who had a long history of plundering and ravaging the east coast of Denmark.

One of the principal targets of the upcoming crusade was Nyklot’s base at Dobin. This settlement was a “famous piratical town,” according to Danish chronicler Saxo Grammaticus. It was situated 50 miles east of Lubeck and eight miles south of Wismar Bay on the Baltic Sea. When Nyklot learned that the Saxon and Danish crusaders were targeting his base at Dobin, he launched a pre-emptive strike on June 26 against Lubeck, leading a large naval force that sailed unopposed into Lubeck’s harbor. Over the course of a two-day amphibious raid, Nyklot’s Obotrites plundered the town, torching large portions of it, and killed or captured all of its residents.

As many as 40,000 Saxon, Danish, and Polish crusaders followed the cross in the Wendish Crusade. Duke Henry of Saxony, Duke Conrad I of Zahringen, and Archbishop Adalbert of Bremen led the northern army. It struck out from Artlenburg in mid-July with its main objective being Dobin, which lay 75 miles to the northeast.

Nyklot successfully repulsed a Danish war party that arrived by sea. This did not deter Henry, though; he pressed on despite the loss of Danish support, systematically reducing pagan strongholds along his path.

Despite papal instructions not to negotiate a truce with the Wends, Henry did exactly that. In return for leaving Dobin untouched, Nyklot agreed to pay an annual tribute and convert to Christianity. The pagan leader later reneged on his pledge. In lieu of seizing Dobin, Henry took possession of a pagan village on a large lake 12 miles south of Dobin. He subsequently founded the town of Schwerin at that site.

In early August, Albert the Bear and Bishop Anselm of Havelberg led the southern crusader army on a 130-mile march from Magdeburg to their first objective, Demmin, which was a key stronghold of the Liutizians. When he reached Demmin, Albert left half of his force to besiege the town. He continued eastward with the rest of his army to Stettin, which was his final objective. When he reached Stettin, Albert found that Roman Catholic Bishop Otto of Bamberg had been living at the city for some time. Having no further business at Stettin, Albert countermarched to Demmin. Although he tried to capture it with his full force, he was unable to do so, and so returned home having achieved nothing of any importance.

That was not the case with Henry, though. The young Duke of Saxony had gained a large tract of land east of the Elbe during the crusade, and he had every intention of taking more territory from the West-Slavic pagans in the future.

After the crusade, Henry wed Princess Clementia, the youngest daughter of Conrad of Zahringen. Henry subsequently made a formal claim to King Conrad III for the Duchy of Bavaria on the grounds that he was heir to it following the death of his mother Gertrude. But Conrad, who had recently returned from the Holy Land, would not alter the status quo. Henry tried unsuccessfully to take Bavaria by force in 1150, which prompted Conrad to dispatch his chaplain to stir up unrest among some of Henry’s vassals in Saxony. The dispute between the duke and king came to an abrupt end when Conrad III died in February 1152.

On his deathbed, Conrad recommended that the German nobility select for the throne his 30-year-old nephew, Duke Frederick III of Swabia. Frederick was a sound candidate because he appealed to both of the rival dynastic houses. Frederick’s mother had been a Welf, and his father had been a Staufen.

Frederick I was crowned King of Germany on March 4, 1152. At the outset of his reign, he controlled both Swabia and Franconia, and initially was not interested in amassing more allodial territory for himself. He assured his Welf cousin Henry that he would restore Bavaria to him.

Conrad III had never risen to the office of Holy Roman Emperor, because he had failed to make the journey to Rome to be anointed. Frederick was not about to make the same mistake. The new German king planned to conduct an expedition to Italy to assert his control over the wealthy cities of Lombardy, as well as visit to Rome to be anointed emperor by Pope Eugene III. He also promised the pope to drive back the Normans of the Kingdom of Sicily who were expanding northward.

As the presumptive Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick controlled not only vast lands north of the Alps, but also the northern half of Italy. This included the city-states, or communes, of Lombardy, which had become extremely wealthy through trade. These city-states were in the process of breaking away from their feudal lords and becoming quasi-independent, self-governing entities.

Frederick departed with 7,200 troops for Italy in October 1154. The expedition would be the first of five he would undertake to Italy. Duke Henry of Saxony accompanied him, bringing 1,800 knights, which constituted one-fourth of the king’s army. At an assembly convened by Frederick at Roncaglia in 1154, representatives of Como, Crema, Lodi, and Pavia accused the rulers of Milan of committing high treachery. After weighing these complaints, Frederick—whom the Italians called “Barbarossa” because of his red beard—instructed the Milanese to refrain from obstructing the actions and commerce of the complainants. The Milanese refused on the grounds that it would seriously erode their power and reputation in Lombardy. Frederick therefore placed an imperial ban on Milan.

Afterwards, Frederick marched to Rome. Pope Eugene III had died in 1153, and by the time Frederick reached Rome, it was ruled by Pope Adrian IV, who had been installed in December 1154. Frederick reached Rome at a point in time when the people of Rome were involved in a heated dispute with the Papacy. The people’s army barred Frederick from entering Rome, but he and Pope Adrian, with their respective entourages, snuck into the city and conducted the imperial coronation without incident. The Romans revolted when they learned that the coronation had been held without their consent, and Frederick and Henry proceeded to crush the rebellion with overwhelming force.

Exhausted after having fought battles in both Lombardy and Rome, the German princes in Frederick’s army now refused to undertake a military expedition against the Normans in Sicily. Frederick had no choice but to lead his exhausted troops back to Germany. Henry had performed with such distinction during the Italian campaign that he was henceforth known as Henry the Lion, Duke of Bavaria and Saxony.

Before departing for Italy, Emperor Frederick had convened a general assembly in 1152 to address the dispute over control of Bavaria. Henry lobbied with great determination to add the Bavarian duchy to his holdings. In 1154, therefore, Frederick granted the Duchy of Bavaria to Henry the Lion.

The principal reason that Frederick awarded Bavaria to Duke Henry of Saxony was that he needed his support for his planned expedition to Italy later that year. The formal transfer of the Duchy of Bavaria to Henry the Lion occurred on September 17, 1156, after the German armies had returned from Italy. Henry was now both Duke Henry III of Saxony and Duke Henry XII of Bavaria.

Henry the Lion’s power was growing rapidly by the mid-1150s. In addition to control of Saxony and Bavaria, a general assembly held at Goslar in 1154 granted Henry the right to invest the Slavic bishoprics of Mecklenburg, Oldenburg, and Ratzeburg. Archbishop Hartwig of Hamburg-Bremen wanted this power for himself; he resented Henry’s ever-increasing powers and became one of his most ardent enemies.

Although Henry had won a great political victory in obtaining the Duchy of Bavaria, he paid little attention to it. It was in his northern Duchy of Saxony that his true wealth and power lay. In Saxony he possessed numerous counties, controlled 50 churches, and had 400 ministerial knights, called ministerialis, employed protecting his properties.

After Frederick’s first expedition to Italy, Henry had time to focus on the welfare of his duchies and administer his Slavic lands. He founded new cities and undertook infrastructure improvements in all three of these areas. Henry founded the town of Munich in 1157.

Frederick invaded Poland that same year to enforce his feudal rights over the Polish king, who was his vassal. King Boleslaw IV of Poland had refused to pay homage to Frederick and to remit the 500 gold marks annual tribute owed to the emperor. Henry the Lion dutifully assembled his Saxon forces, and headed east with the rest of the imperial army. Barbarossa’s imperial forces crossed the Oder River and took the Poles by surprise. The ensuing rout of Polish forces at Posen compelled Boleslaw to sue for peace. As punishment for his transgressions, Frederick raised the annual tribute to 2,000 gold marks per year.

For his loyal support in the first Italian campaign, as well as the Polish campaign, Frederick was willing to give Henry almost completely free reign to expand Saxony to the east and administer it as he saw fit. The emperor at that point in time had no designs on Saxony. Indeed, Frederick dreamed of establishing a vast Hohenstaufen royal domain composed of Alsace, Burgundy, Swabia, and Lombardy that he would leave to his descendents. It would prove to be an unattainable goal, though.

Frederick Barbarossa’s second expedition to Italy began in 1158. At the time, Milan, Brescia, and Crema were at war with Lodi and Como. Henry the Lion arrived with key reinforcements towards the end of the four year campaign.

The 15,000-strong Imperial army laid siege to Crema in July 1159. The fortified city boasted double walls and a water-filled moat. The besiegers employed bombardment, mining, and massive siege towers in a bid to capture the city. The defenders surrendered in January 1160. Frederick then ordered his troops to destroy the city.

Frederick’s next objective was the capture of Milan. The imperial army besieged the city on May 29, 1161. Frederick received two waves of reinforcements. The first group of reinforcements arrived in March. The second wave in August consisted of Henry the Lion and his brother Welf, who brought with them 1,500 Saxon troops. The reinforcements tipped the balance in favor of the Imperial army. Milan capitulated on March 1, 1162. Frederick gave Milan the same treatment he gave Crema: the imperial army razed the city and drove its people into the countryside.

In both Bavaria and Saxony, but particularly in the latter, Henry the Lion’s commercial and municipal initiatives had a positive effect on the prosperity of medieval of Germany. His gains, though, were often made at the expense of others.

Lubeck was a case in point. Since the port technically lay outside the borders of the Holy Roman Empire, Henry was able to exert control over it without interference from the imperial diet. Under Count Adolf of Holstein’s rule it had become a prosperous Baltic port. Henry had demanded early in his rule that Adolph, who was his vassal, share half the profits of the port with him. When Adolf refused, Henry ordered the market closed. Shortly afterwards, Lubeck was destroyed by fire.

Henry rebuilt the port in 1160. Over the course of the next two decades, he oversaw the construction of a large cathedral and outer walls to protect it from Slavic raiders. Possession of Lubeck gave Duke Henry a base from which to project his power into the Baltic Sea and along its southern coast. He granted trading privileges to maritime merchants and gave them a safe harbor from which to conduct their trade.

For a decade after the Wendish crusade, an uneasy peace existed between Henry the Lion and Nyklot. During this period, pagan pirates continued to raid the Danish lands in the western Baltic. “Piracy was so unchecked that all of the villages along the eastern coast [of Denmark] were empty of inhabitants, and the countryside lay untilled,” wrote Danish chronicler Saxo. “Zealand was barren to the east and south, and languished in desolation.”

The Slavic pirates reaped enormous profit from selling Danish slaves in their markets. Henry turned a blind eye to the raids conducted against the Danes, largely because the Slavs paid him large sums not to interfere with their illicit activities.

But this was not enough to satisfy Henry’s desire to squeeze as much revenue as possible from the occupied pagan lands. Henry went to war against the Slavs again in 1158. He spent the next eight years battling Nyklot and his progeny. In these wars, the Saxon armies enjoyed significant technological advantages over the pagans. One reason was that the Saxons had better horses and armor than the pagans. Another reason was that their siege equipment could easily reduce Slavic wooden castles and town walls. When besieging Slavic strongholds, Henry used a variety of siege engines, including covered structures, battering rams, and siege towers, all of which were built onsite. Once the Saxons had conquered a town, they built stone fortifications on the site that were largely impervious to pagan attacks.

Henry invaded the remaining lands of the Obotrites in 1158. During the campaign that year, he briefly imprisoned Nyklot. After a lull in the fighting, Henry allied himself with Danish King Valdemar in 1160 and resumed his offensive against the Slavs. Valdemar and his Danish raiders conducted amphibious operations along the coast, while Henry and Count Adolf conducted joint operations inland.

Nyklot attempted a scorched-earth tactic. He ordered his people to abandon their settlements at Ilow, Schwerin, and Dobin. Before departing for the forests and swamps to the east, the retreating Slavs set fire to their wooden forts. Henry defeated Nyklot’s two sons, Pribyslav and Vratislav, at Mecklenburg. Meanwhile, a Saxon force killed Nyklot while he was foraging near his stronghold at Werle. Henry annexed most of the land that Nyklot had abandoned. However, he returned Werle on the Warnow River to Nyklot’s remaining offspring.

Nyklot’s sons continued to resist Saxon rule from their base at Werle. In 1161 they launched a raid against Guncelin of Hagan, Count of Schwerin, who was one of Henry the Lion’s principal vassals in the conquered Slavic lands. After inflicting damage on his lands, the brothers split up in an attempt to evade capture.

Henry the Lion reacted quickly to the raid. He sent Count Adolf and his troops in pursuit of Pribyslav, while Henry and Guncelin attacked the younger brother Vratislav, who was known to be at Werle. Henry succeeded in capturing Vratislav, whom he imprisoned in Brunswick. But Pribyslav remained at large.

After Henry’s Saxon army captured the pagan stronghold of Werle in 1163, Pribyslav forged an alliance with the co-rulers of Pomerania, Duke Boguslaw and his younger brother Duke Casmir. By doing so, he helped to raise an army large enough to challenge the Saxons in open combat. The Pomeranian dukes wanted to prevent the Saxons from encroaching on their territory, so they were eager to go to war against Henry the Lion.

Pribyslav subsequently attacked the camp of the Saxon vanguard led by Adolf on the Pomeranian frontier on July 6, 1164. Henry hurried forward with the main body; however, the Slavs had slain Adolf in their savage assault on the vanguard. While the Slavs were plundering the camp, Henry launched a vicious counterattack with his main force. He succeeded in routing the Slavic-Pomeranian army in what became known as the Battle of Verchen. Yet Pribyslav escaped and found a safe haven in Pomerania. Infuriated by Pribyslav’s continued attacks, Henry ordered his troops to burn Demmin to the ground.

Henry abandoned his wife, Clementia, during this time because of a long-running dispute with his Zahringen in-laws. Henry then married Princess Matilda, the daughter of powerful English King Henry, in 1168. By marrying Matilda, Henry became one of the most powerful princes in Europe in the 12th century.

Having learned of Pribyslav’s conversion to Christianity in 1167, Henry agreed to give the Slavic chieftain a fief in Mecklenburg. But first Henry demanded that Pribyslav recognize the Duke of Saxony as his overlord. Pribyslav consented to the terms. At that point, Henry’s long war in the Slavic lands drew to a close.

Henry set out on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1172 with 1,000 of his followers. Upon his arrival, he consulted with the Knights Templars about a possible military expedition. But the Templar senior leadership said it was not a propitious time for a campaign. Before departing for home, the duke made a sizeable financial contribution to the Templars so that they could purchase additional equipment.

After his fifth and final expedition to Italy, Frederick returned to Germany in autumn 1178. He partly blamed Henry, who had declined to reinforce him during an emergency meeting held early in 1176 at Chiavenna near Lake Como, for the defeat that the Milanese had inflicted on his imperial army at Legnano on May 29 of that same year.

In a settlement that Barbarossa reached with Pope Alexander III after Legnano, the emperor agreed to return control of investiture of the bishops in Germany to the Papacy. When Frederick ordered Henry to restore the remaining church lands of which he had taken possession, Henry refused. This gave Frederick cause to summon Henry to face judicial action.

The emperor had ordered Henry in 1177 to remove his ally, Gero of Schowitz, from the position of bishop of Halbertstadt and replace him with Bishop Ulrich, whom Henry had removed from office 17 years earlier. Bishop Ulrich was one of Henry’s most bitter and relentless foes. When Henry returned from campaigning against the West Slavs that year, he found that Ulrich had built a fortress in Halbertstadt that he intended to use as a base of operations against the duke. Henry destroyed it, but Ulrich built it a second time. Henry destroyed it again.

While Frederick was on his final expedition to Italy, Henry fought not only with Ulrich, but also with Archbishop Philip of Cologne. Henry’s enemies attacked and looted his castles and towns in Westphalia. Henry’s ecclesiastical foes also sought to have the emperor intervene on their behalf. Barbarossa heard their complaints at an imperial diet in Speyer on November 11, 1177. He was sympathetic to them, and he issued a summons for Henry to appear at Worms in January 1179 to respond to the charges against him.

When Henry failed to appear, Frederick issued another summons in which he instructed the wayward duke to appear in Magdeburg in June. Yet another hearing was scheduled for January 1180, but he failed to appear then, as well. Imperial law stated that three summons should be issued to the accused before a judgment was made without the input of the accused.

As a result of Henry’s failure to appear, the emperor issued a ban against him. Under German law, Henry’s refusal to respond to an imperial summons was tantamount to high treason. Frederick had his imperial officials draw up a document for publication that would set forth Henry’s failure to perform his feudal duties, as well as specific treasonous acts.

Frederick resolved in April 1180 that Henry was to forfeit the Duchy of Saxony. The emperor proceeded to carve Saxony into smaller principalities. Specifically, Westphalia was to be removed from the Duchy of Saxony. Frederick gave the Duchy of Saxony to Margrave Albert of Brandenburg, Henry’s old rival. But before he did so, he gave portions of it to Archbishop Philip of Cologne and Bernard of Anhalt, who was Albert’s younger son. Three months later, Frederick decided that he would also take the Duchy of Bavaria away from Henry.

While these proceedings were under way, Henry went to war against his regional foes in Saxony and the Rhineland. Adolf of Schauenberg, Bernard of Ratzeburg, and Guncelin of Schwerin all remained loyal to the new Duke of Saxony. Because of his superb generalship, Henry gained an advantage over them all. First, he captured Halbertstadt and made Bishop Ulrich his prisoner. Second, he outmaneuvered the forces of the archbishops of Cologne and Magdeburg and compelled them to raise their siege of Haldensleben. Third, he defeated an army co-commanded by Louis of Thuringia and Bernard of Anhalt in a pitched battle at Weissensee on the Unstrut River. Henry not only took Louis prisoner, but also took 400 enemy soldiers into captivity. His only major setback during the civil war in Saxony occurred when he was unable to capture Goslar.

The tide of the civil war turned against Henry when Barbarossa took the field against him. Before doing so, the emperor ordered all of Henry’s vassals to join him on pain of losing their fiefdoms if they failed to do so.

With the dukes and princes of Germany rallying to his banner, Frederick was able to defeat Henry in the field. The former Duke of Saxony tried to get foreign reinforcements from Denmark and England, but was unsuccessful in those efforts. His father-in-law, King Henry II of England, had no intention of going to war with Frederick on his behalf. As for King Valdemar of Denmark, his power had increased to the extent that he no longer needed Henry as an ally.

After losing several pitched battles, Henry reluctantly admitted defeat and submitted to Frederick. Frederick was so deeply moved by Henry’s submission that he agreed to allow Henry to retain two cities of his patrimony—Brunswick and Luneberg. The emperor’s mercy also was a product of the intervention of powerful secular and religious leaders in Western Europe, including King Henry II of England, King Philip II of France, and Count Philip of Flanders. They all urged Barbarossa to show leniency towards Henry. Even Pope Alexander III wrote to Frederick on Henry’s behalf.

Because of this, Frederick was more merciful than he might otherwise have been. Frederick decided to banish Henry from Germany for an unspecified period of time for his own good. Barbarossa did this because he believed that one or more of Henry’s enemies might try to assassinate him. Under the terms granted to him, Henry was instructed to request the emperor’s permission if he chose to return to Germany at a future point in time.

Henry departed Germany in 1182. He became a member of his father-in-law’s royal court. Henry requested and received permission to return to Saxony in 1185. But on the eve of Barbarossa’s departure in March 1188 to participate in the Third Crusade, the emperor ordered Henry to leave the country again, fearing that Henry would try to regain some of his lands by force.

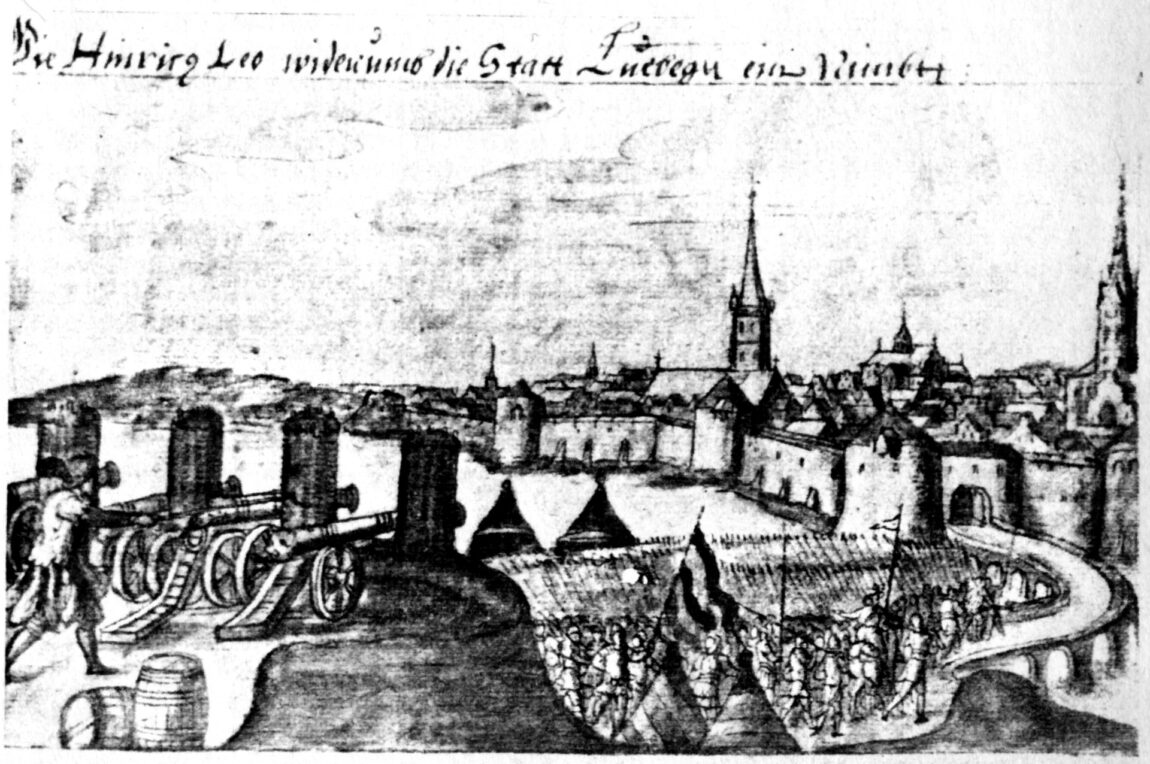

Once Barbarossa had departed, Henry promptly returned to Germany without the emperor’s permission. The former Duke of Saxony raised an army with the help of some of his former vassals and won a quick victory when he captured the wealthy town of Bardowick in Luneberg.

During the long arduous trek across Eastern Europe and Anatolia, Frederick drowned while fording the Saleph River in south-central Anatolia. His successor, King Henry VI, was crowned in April 1191. He defeated Henry the Lion in the field in 1193 and banished him from Germany a third time. But Henry returned again in 1194; this time, however, he had no hostile intentions. Aware that he was near the end of his life, he pledged to the new emperor that he would no longer take up arms in Germany. Henry the Lion, the former duke of Saxony and Bavaria, died in Brunswick on August 6, 1195.