By Eric Niderost

The U.S. sloop of war Constellation was sailing off the coast of Africa, not far from the Congo River, and both officers and crew were enjoying a night so beautiful it seemed almost like a dream. The sea was flat calm, as smooth and placid as a mill pond, and the moon cast its beams brightly on the shimmering, mirror-like waters.

It was just after dusk on September 25, 1860, and the crew was headed back to St. Paul de Loando, their supply base in Portuguese Angola. Some of the crewmen began to laugh and sing, and even the officers pacing the quarterdeck seemed to be in a more relaxed mood. The Africa Squadron was far from being considered choice duty. Its official mission was to intercept slave ships before they could deliver their human cargo to the Americas, particularly Cuba. But most of the time the bluejackets saw little action, and they had no choice but to endure a daily grind of torrid heat and mind-numbing boredom.

Suddenly a lookout perched on the fore topsail yard broke the spell by yelling, “Sail ho!” For a breathless moment it seemed as if time had stopped; the singing ended, laughter was stilled, and everyone seemed frozen in place. “Where away?” asked the officer of the deck through his speaking trumpet, and the lookout answered, “About one point forward of the weather beam, Sir!” Every officer and man looked in the direction indicated and, sure enough, a ship could be seen in the distance, the moonlight making it seem like a phantom.

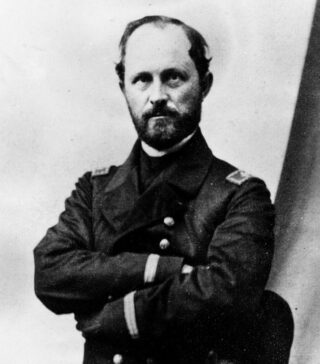

Every ship in these waters had to be inspected, but as soon as the “phantom” saw it had been spotted it tried to run. Constellation gave chase. For the next three hours or so the slaver bark Cora matched wits and seamanship with the Constellation’s officer of the deck, Lieutenant Donald McNeil Fairfax. The lieutenant was a skilled seaman, at one point even ordering the sails to be wetted down so they would catch more wind.

To show that the Constellation meant business, the number one gun crew was told to load its 32-pounder cannon with solid shot. Fairfax then ordered a shot across Cora’s bow, the traditional means of ordering a ship to heave to. When Cora ignored the warning and continued on, Constellation’s crew rejoiced, because this was confirmation, if confirmation was needed, that the ship they were pursuing was indeed a slaver.

Excitement aboard Constellation reached a fever pitch. Every man and boy scrambled on deck, even those who should have been sleeping, preparing for their next turn on watch. It was not just the excitement of the chase that was causing the adrenaline to course through their veins: there was also money to be had. A captured slave ship and all its fittings would be sold, with half the proceeds set aside for the care of sick and aged sailors. The other half would be divided among officers and men. In addition, Congress offered a $25 bounty for each slave set free.

By about 10 pm Constellation was gaining ground on its quarry, and another shot was fired, but still the slaver captain paid no heed. The Cora started dumping things overboard to lighten its load, and even let loose one of its ship’s boats in a vain attempt to distract the fast approaching U.S. vessel. More cannons were fired, and one of the blasts damaged some of the slaver’s rigging. Constellation dared not send cannonballs though the hull for fear of hitting the tightly packed slaves in the bowels of the ship

When the slaver was within hailing distance it was ordered that the cannon be loaded with shell and fuse. A shell explosion would be far more devastating than solid shot and would cause more extensive casualties. The order was shouted loud enough for the slaver crew to hear it across the water. The threat of shellfire finally persuaded them to furl their sails and surrender.

A boarding party was sent over to take formal possession of the newly captured prize. They were armed with pistols and cutlasses; a sensible precaution, because usually a slaver’s crew were murderous thugs of the lowest order.

But there was one question on everyone’s mind: how many slaves were aboard? The answer was soon forthcoming. The slaver carried more than 700 slaves. The moment the crew heard these words they spontaneously filled the air with three deafening yet joyous cheers. Both officers and men would gain prize money for all, plus the satisfaction of doing their duty.

The Constellation was a relatively new ship, built in 1854, and was the last all-sail vessel made for the U.S. Navy. Most nations, including the United States, were switching over to steam-powered vessels, though steamers still usually had masts, spars, and sails as reassuring traditional backups. But the Africa Squadron’s roots go back into the 18th century.

In 1787 the Constitutional Convention passed a compromise provision that would ban the transatlantic slave trade in 1808. At the time slavery was, on the whole, a dying institution. Slaves were costly, and southern planters were afraid of being outnumbered by their human “property.” There were also some glimmers of enlightenment. Many Americans grasped that slavery was fundamentally evil. But the invention of the cotton gin in the 1790s changed both attitudes and the economic environment in the South.

The gin deseeded cotton efficiently and made the crop enormously profitable. Cotton plants needed constant tending, including chopping or weeding. Cotton flowers soon gave way to cotton bolls the seed-bearing capsules that contain the cotton fiber. The picking could then commence. Large plantations needed large gangs of laborers, so slavery quickly revived. The process was given added impetus by the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The cotton boom and slavery moved west into the new territory and helped create new slave states like Mississippi and Alabama.

After the slave trade became illegal in 1808 there were sporadic attempts by the U.S. Navy to halt the traffic. The U.S. government and, by extension, the American people, simply lacked the will at this stage to invest enough resources to stop this infamous trafficking in human beings.

The situation was further complicated by American sensitivity about having Royal Navy vessels inspect American-flag vessels for slaves. The British Royal Navy was the most powerful navy in the world and was in a position to put a dent in, if not altogether abolish, the horrors of mid-Atlantic slave trafficking. Indeed, the British West Indian Squadron chalked up an impressive record in its first 50 years or so of existence.

But part of the process involved the “right of search.” Many countries signed treaties allowing the Royal Navy to stop and search their vessels. These nations included France, Spain, Portugal, and Holland. The United States did not agree to this tenet, in part because of bitter memories of the years just before the War of 1812. At that time British warships stopped American merchant vessels with impunity, and also impressed American sailors to serve in the Royal Navy against their will.

Slavers of different nations quickly took note of the situation and hoisted an American flag when a British warship was spotted on the horizon. Protected by the Stars and Stripes, the slavers blithely sailed away while British Royal Navy officers gnashed their teeth in frustration. But the Americans would not budge on this point. Matters remained about the same until the 1840s.

In 1842 the Anglo-American Washington Treaty, also called Webster-Ashburton Treaty, marked a new milestone in suppressing the seaborne slave trade. The treaty stipulated that the United States maintain an Africa Squadron composed of ships that had an aggregate of 80 guns. The American African Squadron would operate independently of the British, but for the first time real cooperation was mandated. The United States was now committed to a permanent patrol, not just sporadic voyages of dubious worth. It must have seemed a very promising start to American and British abolitionists, but unfortunately the progress was more apparent than real.

Abel P. Upshur was Secretary of the Navy when the Africa Squadron was officially established in 1842. He was a visionary administrator who was open to new concepts and innovations. For example, he helped modernize the U.S. Navy through the addition of steam-powered vessels to the fleet. Yet as a Virginian and a slaveholder, he seemed to be indifferent to the fledgling Africa Squadron so recently placed under his jurisdiction.

In 1843 Captain Matthew Galbraith Perry was appointed flag officer of the Africa Squadron. Perry was truly an old sea dog with vast experience in the naval service. He is remembered in part for having opened up a reclusive feudal Japan in the 1850s.

Perry’s new four-ship command was minuscule. It included the frigate Macedonian, sloop of war Saratoga, sloop Decatur, and the brig Porpoise. Upshur all but torpedoed the squadron’s effectiveness with a letter of instruction. The missive forthrightly declared that its mission and chief purpose was that the “rights of our citizens in lawful commerce” were not to be “improperly abridged.” Showing the flag and making sure American trade flowed smoothly from all points of the compass was the squadron’s main duty. The suppression of the slave trade, which was the primary reason the squadron was established, came in a distant second.

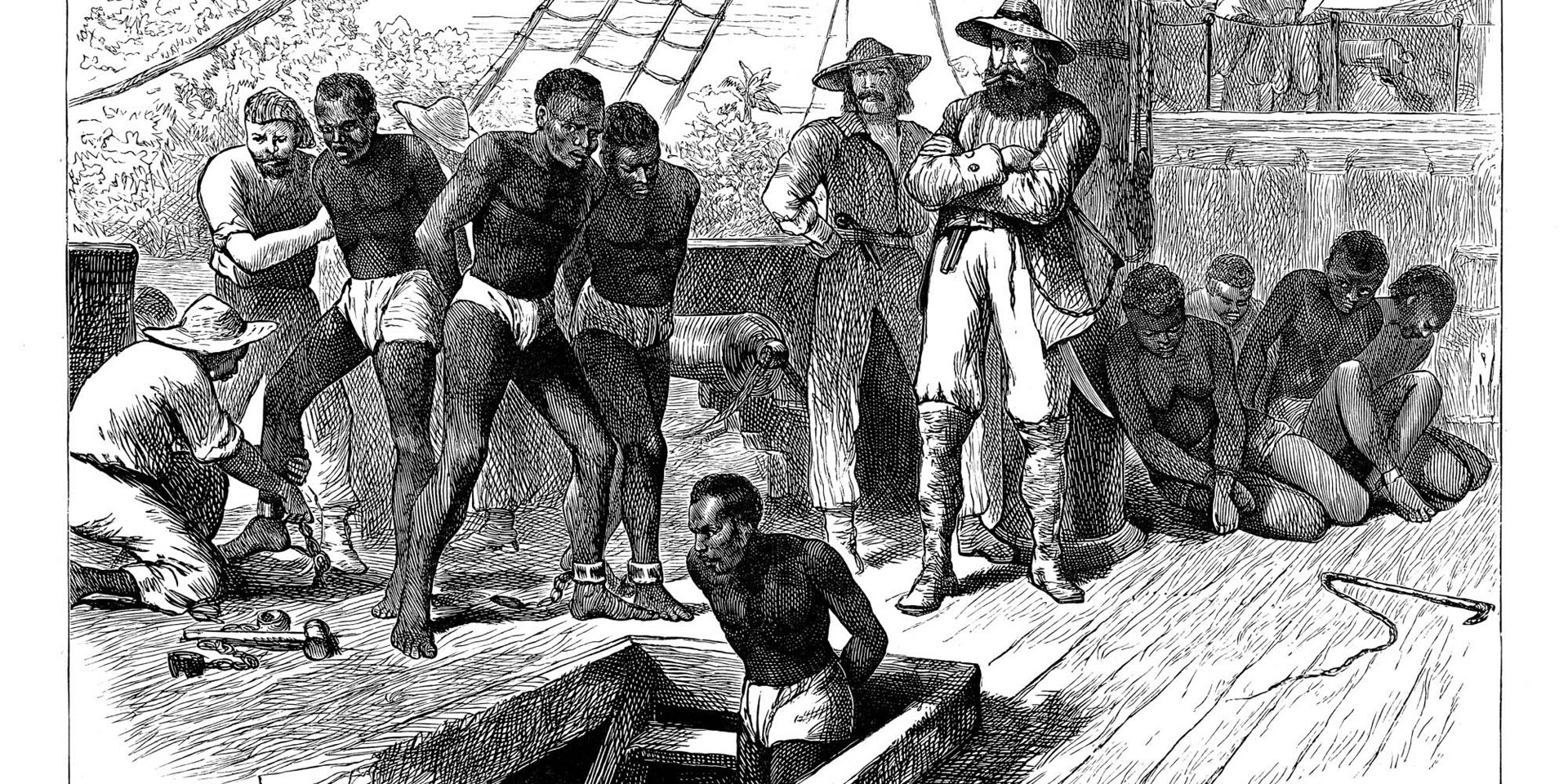

Slave ships usually began their voyages disguised as routine merchant vessels, with their papers in order and nothing outwardly suspicious. But perceptive observers could easily spot the telltale signs of a would-be slaver, signs that its captain and crew could do little to disguise. Usually there was stored lumber, which would eventually be used to create a slave deck to store the captives. Below the slave deck would be stacks of iron bars used for ship’s ballast. But among the ballast would be barrels or pipes of water and sacks of farina, a grain that, when mixed with oil, was the main food for the slaves during the voyage.

Other telltale signs included two sets of ship’s papers in the event the second set was discovered. Yet another sign was the presence of a nearly all foreign crew on an American flagged vessel. Sailors in the 19th century were a tough breed, inured to hard work, bad food, and wretched conditions. Congress had only abolished flogging in the Navy and Merchant Marine in 1850. Yet witnessing the horrors of the slave cargo holds was a disturbing and unforgettable experience for most bluejackets.

The physical condition of many slaves was also shocking, with naked bodies “covered in loathsome scabs” and “tongues white from lack of water.” Others had burning fevers, or were speckled with human waste or vomit from seasickness. The cargo holds were visions of hell, according to Ensign Wilburn Hall, who was a slaveholder himself.

Captives freed from slave ships were returned to Africa, but not to their home regions. The reason was simple: if returned home, chances were high they would be recaptured and enslaved once again. The British landed their newly freed slaves at Sierra Leone, one of the colonies they had established on the west coast of Africa. In similar fashion, captives freed by the U.S. Navy were sent to Liberia, the fledgling nation established by the American Colonization Society for American blacks.

Gradually, most nations followed the lead of the United States and banned the Atlantic slave trade; however, making the slave trade illegal did not halt the traffic. The profits were just too great. Throughout most of the 19th century the United States was not the primary market for the clandestine sale of African slaves. Virtually all slaves were shipped to Brazil and Cuba, and after Brazil finally banned the trade in 1850, Cuba became the main market.

Slavery was still legal in Cuba, then a Spanish colony, and the island was developing its own stable cash crop. For the American South the cash cop was cotton, while for the Cubans it was sugar. By 1860, Cuba was home to 1,400 sugar mills producing 450,000 tons of the sweet crystal. Nearly 370,000 chattels were working to meet the growing demand but they were not enough. More slaves were needed.

To those without a sense of morality or a drop of compassion for fellow human beings, Cuba’s needs afforded a great opportunity for profit. One would think that southern cities would be the centers of the flourishing illegal trade to the island. But New York with its strong trade links to the South was the clandestine center of the slave trade. The risks were small, the rewards great. It made sense to many businessmen to invest clandestinely in slave ventures.

The Cuban demand for slaves eventually leveled off, but it did not disappear entirely. In the mid-to-late 1850s the desire to reopen the slave trade to the United States, long dormant, started to spring to malevolent life. King Cotton dominated the South, but more workers were needed. The concept of natural increase, whereby existing slaves filled the demand by having more children, no longer met the soaring labor demands. As the country began to split along regional lines, the South’s feelings toward the North and its “evil” abolitionists came close to paranoia. By that time, the South supplied much of the world’s cotton. To maintain that economic position, many individuals started to think that reopening the slave trade was the only viable solution.

The laws of supply and demand exacerbated the South’s seeming plight. Simply put, the growing scarcity of slave labor drove up the price of the chattels that were still available on the market. One Southern commentator complained that the price of slaves had already reached a point beyond the means of small planters. Able men (i.e., skilled workers) were sold as high as $1,835, which equates to approximately $20,000 in today’s economy.

William Lowndes Yancey, a rabid pro-slavery and secessionist Alabama politician, asked, “If it is right to buy slaves in Virginia and carry them to New Orleans, why is it not right to buy them in Cuba, Brazil, or Africa and carry them there?”

On May 10, 1858, a so-called Commercial Convention met at Montgomery, Alabama. James DeBow, editor of the commercial journal, was one of the organizers, and Yancey lent his support. “Resolved, that slavery is right, and that, being right, there can be no wrong in the natural means to its formation,” declared the convention. But this statement was only the warm-up for the convention’s real bombshell: “It is expedient and proper that the foreign slave trade should be reopened, and that this convention will lead its influence to any legitimate measure to that end.”

The U.S. Navy was full of Southern officers, some of them slave owners, and the record shows that in the main they did their duty. But public duty and private convictions are two different things. Southerners were sickened by the sights they witnessed on slave ships. But after the initial shock, they seemed to have rationalized the situation and suppressed any feelings of guilt they had.

It was the voyage of the slaver Wanderer that caused a sea change in the African Squadron, literally and figuratively. The ship, originally built as a yacht, was so swift it easily evaded the sloop of war Vincennes when the latter gave chase in the open ocean. Wanderer’s backers included Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar of Savannah, Georgia. Lamar, yet another secessionist and pro-slavery man, was elated when the ship landed 405 slaves on Jekyll Island under the very noses of the Federal authorities.

But word soon spread of the Wanderer’s clandestine and decidedly illegal feat. Northern papers expressed shock. How could this happen? President James Buchanan was usually depicted as a “doughface,” meaning he was a pliable politician, kneaded and shaped by the many Southerners in his administration. The easy escape of Wanderer seemed to confirm these suspicions. Buchanan was a Democrat, and the newly formed Republican Party was against slavery’s growth. The 15th president of the United States was embarrassed by the Wanderer and wanted to distance himself from his “fire-eating” secessionist colleagues in Washington.

In the late 1850s Buchannan ordered Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey to strengthen the Africa Squadron. Commodore William Inman would have eight ships under his command, and four of them would be steamers. The sloop of war Constellation would be his flagship; the other all-sailing vessels were the sloops of war Vincennes, Portsmouth, and Marion. Yet it was the steamers that were the most welcomed additions, including San Jacinto, Mystic, Mohican, and Sumpter.

This newly augmented Africa Squadron was spectacularly successful, at least when measured by what had gone on before. The Constellation alone captured three slavers, one of which was the notorious Cora. The overall situation was helped by the fact that the squadron’s base was finally moved to the African continent, namely St. Paul Loando in Angola.

It was the outbreak of the American Civil War that finally put an end to the transatlantic slave trade and the Africa Squadron. The reforms, including the introduction of steamers, allowed the squadron to end in a blaze of glory. In a year’s time the squadron caught 14 slave ships and freed 3,032 slaves, which was half the total number that had been liberated from 1839 to 1861.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments