By Mason B. Webb

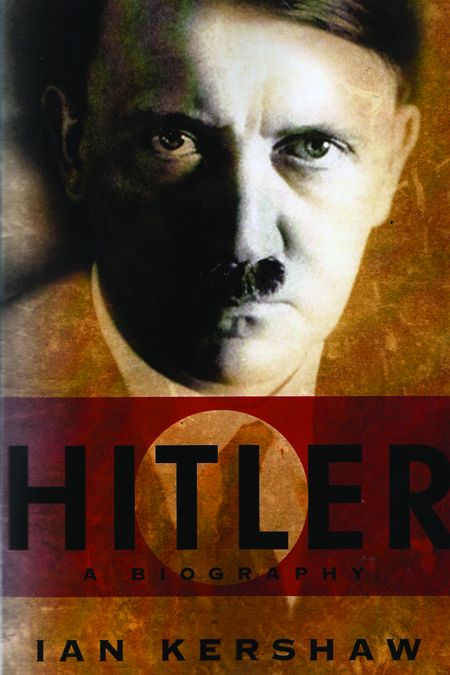

Few men have had an impact on world history equal to that of Adolf Hitler. His megalomania resulted in the deaths of millions and redrew the map of Europe. Even today his influence is still being felt. And, although scores of books have been written about the man, few writers have captured the total personality as completely and penetratingly as has Ian Kershaw in his monumental Hitler: A Biography (W.W. Norton, New York, 2008, 1,056 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $39.95, softcover).

Few men have had an impact on world history equal to that of Adolf Hitler. His megalomania resulted in the deaths of millions and redrew the map of Europe. Even today his influence is still being felt. And, although scores of books have been written about the man, few writers have captured the total personality as completely and penetratingly as has Ian Kershaw in his monumental Hitler: A Biography (W.W. Norton, New York, 2008, 1,056 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $39.95, softcover).

Drawing on previously untapped sources and reexamining previous information, Kershaw, a professor at the University of Sheffield and the acclaimed author of numerous best-selling books of history, shows how Hitler’s troubled childhood and youth built the foundation for his lust for power.

Kershaw then skillfully weaves the reader through Hitler’s personal failures in Vienna and his growing hatred of Jews, his service in Kaiser Wilhelm II’s army in World War I, his postwar ambitions to change Germany’s destiny and seek revenge for the humiliating provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, and the remarkable events that propelled him to the position of the most powerful man in Europe.

The author then brings the tale full circle by recounting Hitler’s at first stunningly successful launching of the war and then the disastrous handling of military operations that led to the Third Reich’s destruction.

The book, a one-volume edition of Kershaw’s earlier two-volume set, is being hailed by critics as “masterful,” “a masterpiece,” and “the definitive biography of Hitler in our time,” and we wholeheartedly agree. A better, more complete portrait of the man is unlikely ever to be written.

Unknown Soldiers: Reliving World War II in Europe, by Joseph E. Garland, Protean Press, Rockport, Mass., 2008, 496 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

As a soldier with the 45th Infantry Division, one of the most battle-hardened outfits in the U.S. Army, Joe Garland saw a lot of action. As a fine writer, he describes a great deal of what he and his platoon went through on the battlefields of Italy, France, and Germany. But, in spite of the fact that he has written more than 20 books, it took him over 50 years to finally put those experiences into words.

Suffering from “writer’s block” he later attributed to then-unknown post-traumatic stress disorder (it was called “battle fatigue” then) as well as “survivor’s guilt,” Garland struggled to convert the scribbled notes he had begun in 1943 into a full-blown manuscript. Only after he started hunting down old buddies and began interviewing them did the book start to take form. It was worth the wait, for he deftly describes his transformation from callow youth, eager for battle, to a grizzled, disillusioned veteran.

As Garland writes in his opening paragraph, “Cold, gray and miserably rainy, New England was awash in the dregs of winter as I boarded the train from Boston’s North Station with a mixed crowd of collegians for the hour’s ride to the Army’s induction center at Fort Devens. I was a Harvard junior of twenty on loan to my country, playing cool but nervous, poised on the brink of the Second of the Worst Wars, and about—not to be pushed—but to leap.”

Another sample of his finely wrought prose, recounting a night in a foxhole a year later at Anzio: “I was temporarily with Nye’s crew … and I took over O’Keefe’s geometrically carved hole (he had the instincts of a mining engineer). My first night I was awakened by the tiny feet of a smallish rat scuttling nervously across my face, reconnoitering, no doubt, such a motionless body in such a neat grave.”

Garland goes on to recount, sometimes using his own notes written from the time, official records, or interviews with his buddies, his musings on life, death, war, and the human condition.

One reviewer called Unknown Soldiers a “masterpiece” while another said it is an “incredible journalistic monument.” It is all those things. And more.

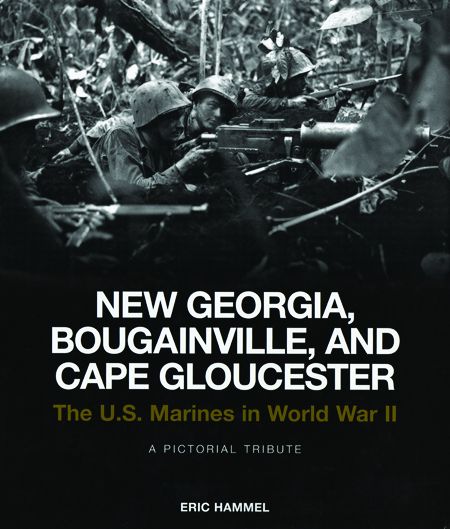

New Georgia, Bougainville, and Cape Gloucester, by Eric Hammel, Zenith Press, Osceola, Wisc., 2008, 168 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover.

New Georgia, Bougainville, and Cape Gloucester, by Eric Hammel, Zenith Press, Osceola, Wisc., 2008, 168 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover.

In his latest pictorial history of U.S. Marine Corps campaigns in the Pacific, acclaimed historian Eric Hammel has assembled hundreds of never-before-published photographs in a volume that graphically depicts the horrors and difficulties of jungle warfare.

Although American Marines had defeated Japanese forces during six months of grueling combat on Guadalcanal and its neighboring, festering islands, more hard fighting lay ahead in the Solomons if American forces were to neutralize Dai Nippon’s powerful naval base at Rabaul.

The battles of New Georgia, Bougainville, and Cape Gloucester, which were a vital part of that campaign, would turn out to be some of the toughest tests for the Marines in the entire war and would prove the mettle of “the few and the proud.”

While Hammel’s narrative is enlightening and compelling, it is the remarkable photos that grab and hold our attention—lines of troops slogging through knee-deep mud, corpses twisted in the agony of death, young faces of Marines filled with hope, fear, and determination. Rarely has one book so dramatically and graphically captured the human side of combat.

As Hammel has written, “There lies within this volume the largest collection of photos of Marines in the Solomons and Bismarcks that has been published to date, or maybe ever will be published.”

Hammel’s work is a fitting tribute to the men who endured unimaginable conditions to wrest these key islands away from a resourceful and determined enemy. He is to be commended for another superb achievement in documenting the legacy of the Leathernecks.

Command of Honor: General Lucian Truscott’s Path to Victory in World War II, by H. Paul Jeffers, NAL Caliber, New York, 2008, 326 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Command of Honor: General Lucian Truscott’s Path to Victory in World War II, by H. Paul Jeffers, NAL Caliber, New York, 2008, 326 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Ask anyone to list the great American generals of all time and the name of Lucian K. Truscott is likely to be noticeably absent. That is probably because Truscott was neither brash nor arrogant, nor a publicity hound wasteful of men’s lives. He was, however, tough, resourceful, and entirely devoted to the men under his command—all qualities that made him one of the greatest generals of his (or any other) generation.

H. Paul Jeffers, a renowned journalist with over 70 books to his credit, has crafted an outstanding biography of this often overlooked American hero. According to Jeffers, the Texas-born, leather-jacketed Truscott, despite his sometimes gruff manner, was an extraordinarily loyal, humble man who led his troops from the front and fought the enemy with a tenacity and resourcefulness that made him one of the most respected commanders in the U.S. Army.

After serving in the cavalry corps during World War I, Truscott rose to the fore in World War II as he formed the first American commando units—which would soon become known as the Rangers—and then commanded the 3rd Infantry Division in brutal combat in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy before being tapped to command VI Corps following Major General John P. Lucas’s perceived failure at Anzio.

After the Anzio breakout and subsequent capture of Rome, Truscott then led VI Corps during Seventh Army’s swiftly successful invasion of southern France during Operation Dragoon in August 1944. So well did he conduct operations that he was chosen to command the newly formed XV Army. It was then back to Italy to take charge of Fifth Army following Mark Clark’s promotion.

Following the destruction and surrender of German forces in Italy and the American victory in Europe, Truscott went on to command the U.S. Third Army in the months after Germany’s capitulation.

A contemporary of his once said that Truscott was the general who “combined all of the best traits of Eisenhower, Bradley, and Patton without any of their flaws.”

Command of Honor is as appealing and honest as the general himself—a story of service and sacrifice by a man who lived for duty, honor, and courage during a time that demanded nothing less.

Iwo Jima: World War II Veterans Remember the Greatest Battle of the Pacific, by Larry Smith, W.W. Norton, New York, 2008, 345 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Iwo Jima: World War II Veterans Remember the Greatest Battle of the Pacific, by Larry Smith, W.W. Norton, New York, 2008, 345 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Of the nearly 70,000 Americans who stormed the sulfurous sands of Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, most were teenagers. Now in their 80s, and with their ranks being thinned at an accelerating pace, their stories have been compiled by veteran reporter Larry Smith into a riveting, first-person narrative that tells what life—and death—were like during those 36 days of merciless, unrelenting combat.

Pulling no punches, the nearly two dozen veterans Smith interviewed paint a portrait in words of horror and heroism beyond measure, sparing none of the hardship or glory of their deeds.

The battle itself was a nightmare. The Japanese, as most people now know, were burrowed into miles of underground tunnels and had every foot of the island zeroed in for their machine guns, mortars, and artillery. No retreat was possible, so a battle to the last man was inevitable. Even while dying, enemy soldiers pulled the pins to grenades and pressed them under their bodies so that they would kill Americans who came to check if they were still alive.

When the smoke finally cleared, some 28,000 combatants lay dead, including 6,821 Americans. It was the Marine Corps’ deadliest battle of all time.

Yet, doubtless because of the price paid, Iwo Jima remains to this day perhaps the most famous and celebrated of all Marine victories, an iconic symbol of devotion to duty and the price of freedom.

Although the battle of Iwo Jima is one of the best-known of all World War II battles, Smith and his interviewees bring a fresh perspective to its telling. Because of the unsparing descriptions of the fierceness of the fighting, Smith’s Iwo Jima is a hard book to read—and an even harder one to forget. Highly recommended.

The Knights of Bushido: A History of Japanese War Crimes During World War II, by Lord Russell of Liverpool, Skyhorse Publishing, New York, 2008, 335 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $14.95, softcover.

The Knights of Bushido: A History of Japanese War Crimes During World War II, by Lord Russell of Liverpool, Skyhorse Publishing, New York, 2008, 335 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $14.95, softcover.

Undoubtedly, many Americans, when they hear the words “war crimes” and “atrocities,” think only of the Nazis and their terrible deeds while tending to forget, dismiss, or be altogether ignorant of what was taking place in Asia and the Pacific. While the Japanese may not have wiped out millions of people in extermination camps, their treatment of conquered peoples, as well as doctors, nurses, and prisoners of war, was no less egregious, no less horrific, no less criminal.

Documenting many of the Japanese atrocities is Edward F.L. Langley, the second baron of Liverpool, in his new book, The Knights of Bushido. Basing his book on evidence and documents produced at various war crimes trials, and from testimony given by eyewitnesses of atrocities to war crimes investigation commissions set up after the war by the Allies to bring the criminals to justice, Lord Russell has created a stunning indictment of Japanese soldiers and officers who perverted the warriors’ code in their brutal treatment of helpless captives.

As Lord Russell writes in the preface, “I regret that it has been necessary to include so much that is unpleasant, but it would have been impossible to have done otherwise without, at the same time, failing to achieve the whole aim of the book, namely to give a concise but comprehensive account of Japanese war crimes. Nevertheless, for every revolting incident which has been described, a hundred have been omitted.”

With powerful text and photos not for the squeamish, The Knights of Bushido makes for uncomfortable, but vitally important, reading.

A Magnificent Disaster: The Failure of Market Garden, The Arnhem Operation, September 1944, by David Bennett, Casemate, Drexel Hill, Penn., 2008, 286 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

A Magnificent Disaster: The Failure of Market Garden, The Arnhem Operation, September 1944, by David Bennett, Casemate, Drexel Hill, Penn., 2008, 286 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Considered one of the worst military disasters of the entire war suffered by the British and Americans, Market Garden, the ill-conceived brainchild of the usually overly cautious Field Marshal Sir Bernard L. Montgomery, Operation Market Garden led to the deaths and capture of thousands of Allied troops.

Since its first publication in 1974, Cornelius Ryan’s A Bridge Too Far has stood as the definitive account of Market Garden, the Allies’ grandiose attempt to seize several key bridges over the Rhine River in Holland by airborne and glider troops in September 1944.

But, as fine a book as A Bridge Too Far was, Magnificent Disaster author David Bennett had long felt that Ryan’s work told only part of the story. Bennett asserts that the Ryan book “is extremely weak on the strategic background and objectives of Market Garden” and that it “fails to convey the fact that Market Garden was an operation by all of Second Army, not just of XXX Corps; the operations of VIII and XII Corps are not even mentioned!”

To correct these oversights and provide a broader, more balanced picture of the entire operation, Bennett has gone back to the original primary written sources while relying less than Ryan did on oral histories.

The result, not surprisingly, is a truer and more complete presentation of the entire operation. In his detailed consideration of logistics, communications, intelligence, and military culture, as well as leadership and tactical enterprise, David Bennett supplies some intriguing conclusions in this, his first book-length work. A “must read.”

An Army in Skirts: The World War II Letters of Frances DeBra Brown, by Frances D. Brown, Indiana Historical Society Press, Indianapolis, Ind., 2008, 264 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $27.95, hardcover.

An Army in Skirts: The World War II Letters of Frances DeBra Brown, by Frances D. Brown, Indiana Historical Society Press, Indianapolis, Ind., 2008, 264 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $27.95, hardcover.

During World War II, over 150,000 women served in the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC). Strongly opposed by some in Congress who disliked the idea of women in uniform, ridiculed by some critics as the “Petticoat Army,” and derided by others as being nothing more than a large group of “loose women” who could march in step, the WAACs (as well as their counterparts in the Air Corps, Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard) performed valuable services, not the least of which was freeing up more men for combat duty.

The service and contribution of these women has gone largely ignored, but Frances DeBra Brown has gone a long way in rectifying that oversight. As she says in the preface of An Army in Skirts, “Those who had signed up for training had been warned that their work would ‘be no picnic for glamour girls”…. Some had a personal stake in the war, as they were the siblings of men in the service and widows of soldiers, sailors, and Marines killed at Pearl Harbor and Bataan. They tackled their training with enthusiasm, prompting one grizzled sergeant to declare that the women recruits learned ‘more in a day than my squads of men used to learn in a week.’”

A talented writer and artist (in addition to dozens of photos, the book is sprinkled with her sketches and watercolors), Brown, through her letters to friends and family, provides the reader with a breezy yet detailed look at life in the WAACs—from training in Georgia and assignments in South Dakota, Florida, London, and Paris—and a life that nearly ended during the German “buzz bomb” raids on London.

Chock full of interesting details and written in a lively style, An Army in Skirts is highly recommended.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments