By Arnold Blumberg

On August 14, 1944, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., paused after his daily staff conference to offer a short speech about the accomplishments of his Third Army. In the mere two weeks since Third Army had burst out of Normandy, Patton could boast, “Third Army has advanced further and faster than any army in the history of the war.” As Patton spoke, Third Army continued its historic advance across France, its sights focused on reaching the Seine River.

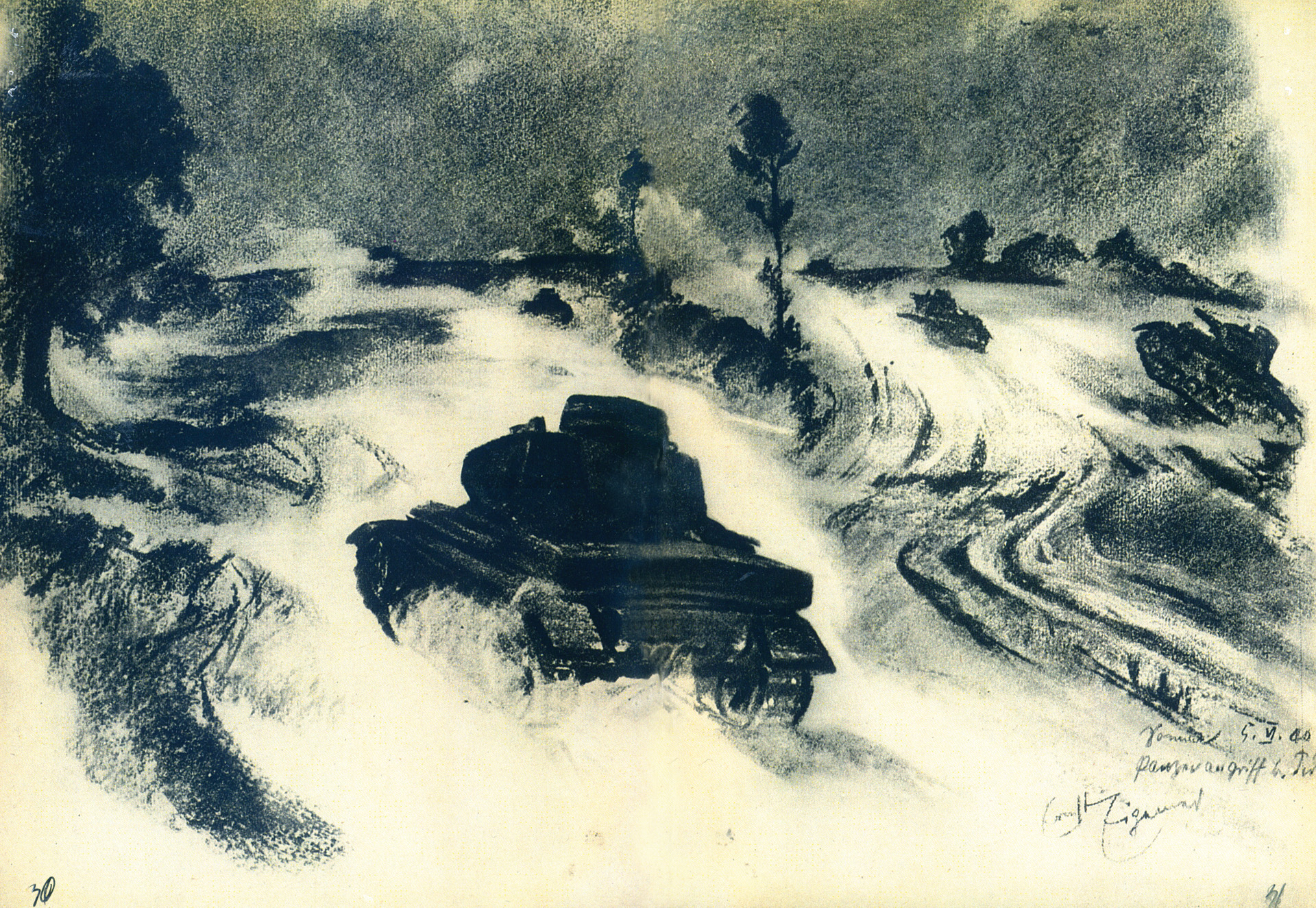

On the day Patton spoke to his staff, Third Army’s XV Corps, under Maj. Gen. Wade H. Haislip, saw its 5th Armored and 79th Infantry Divisions ordered to take up the long envelopment of the Seine River, in place of the shorter envelopment at Argentan, by crossing the Eure River at the city of Dreux 40 kilometers west of Paris and the Seine. The next day, Maj. Gen. Walton H. Walker’s XX Corps, with his 7th Armored and 5th Infantry Divisions leading the way, was directed toward the Eure and the cathedral city of Chartres, while XII Corps, led by Maj. Gen. Gilbert R. Cook, on the Army’s right, witnessed its 4th Armored and 35th Infantry Divisions sweep along the north bank of the Loire River as they dashed for the city of Orleans.

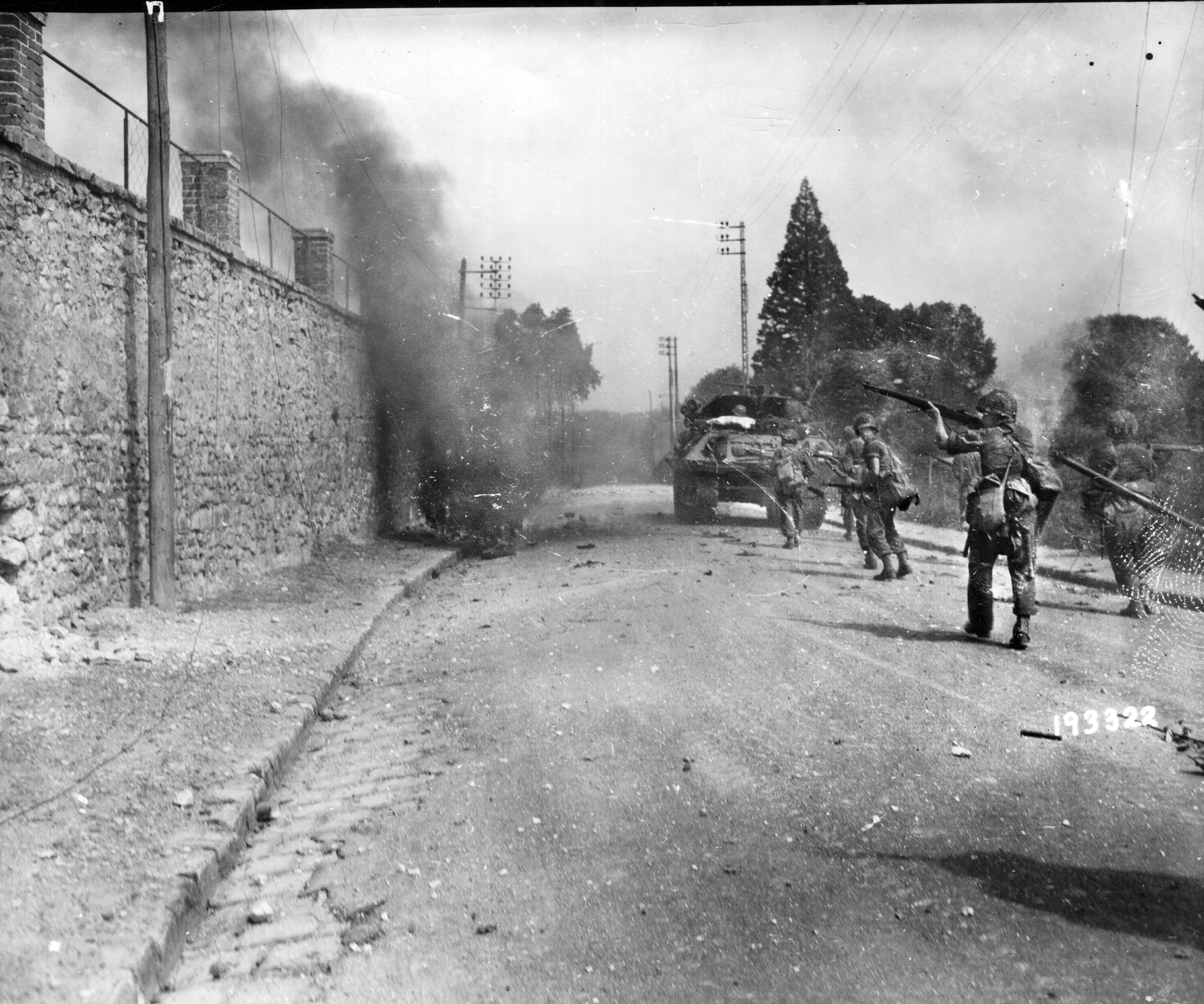

On August 16, Dreux and Orleans fell into Third Army’s hands. First attacked by the U.S. 7th Armored Division on the 15th, Chartres proved a hard nut to crack. The division’s Combat Command B had to withdraw due to bitter resistance from the German defenders, veterans of the 352nd Infantry and 17th SS Panzergrenadier Divisions. It was not until August 18 that the combined might of the 7th Armored and the 5th Infantry Divisions finally wrested control of the town from the enemy. During these operations the main opponents of Third Army were divisions from the German First Army under General Kurt von der Chevallerie just arriving from the Bay of Biscay, along with formations coming south from the Calais area. Desperately trying to form a defensive front to hold the Paris-Orleans Gap and halt Patton’s advance, Chevallerie’s units were thrown into battle piecemeal but were only able to create weak roadblocks that were either bypassed or brushed aside by Patton’s hard-charging tankers and infantrymen.

Despite Patton’s spectacular advances since August 14, his boss, Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley, commander of the U.S. 12th Army Group (composed of the First and Third Armies), ordered Patton to halt his movements on the 16th. The reasons for the stop order included Bradley’s concern that Third Army’s left flank was not properly guarded, as well as the growing Allied supply shortages due to their rapid advances in the past three weeks. However, the next day Bradley partially lifted his order of the 16th and allowed Patton’s XV Corps to move to the town of Mantes on the Seine 50 kilometers northwest of Paris. The XX Corps was to relieve Haislip at Dreux while XII Corps, to conserve

precious fuel, remained in place. The plan now was for the Americans to not only keep an already retreating foe on the run, but also to circle to the rear of the approximately 75,000 German combat troops and their 250 armored fighting vehicles still west of the Seine and north of Mantes. The 5th Armored Division, closely followed by the 79th Infantry Division, sped toward Mantes on August 18, arriving the next day only to discover that the Germans were gone.

On the 19th, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander in northwestern Europe, decided to modify the original Operation Overlord plan, which had called for an Allied halt on the west side of the Seine River after breaking out of the Normandy beachhead. The preinvasion purpose of stopping on the west bank of the river was to allow the Allies to reorganize and build up a secure logistical base from which to clear France of the Germans and then move on to invade Germany. With the entire enemy defense in France collapsing, the new Allied demanded that there be no pause at the Seine, but instead a “dash across the Seine” followed by immediate operations directed toward the Reich itself.

To accomplish this goal Bradley’s 12th Army Group would cross the Seine south of Paris and move to the Troyes-Reims-Amiens line. Meanwhile, to Bradley’s left, Lt. Gen. Bernard L. Montgomery’s 21st Army Group (made up of the British Second and Canadian First Armies) was to cross the Seine between Mantes and Rouen north of the French capital.

The new Allied plan was initiated at 9:35 pm on August 19, when Haislip ordered Maj. Gen. Ira T. Wyche’s 79th Infantry Division to cross the Seine that night. Once troops of the 79th were established on the east bank, a bridgehead of sufficient depth was to be established for a treadway bridge to be built that would be protected from enemy artillery. By the early hours of August 20, Wyche had men of the 313th Infantry Regiment, under torrential rain, crossing in single file along the narrow foot bridge over the dam near the village of Mericourt.

At daybreak, the 314th Infantry Regiment paddled across the river and joined its sister regiment. The divisional engineers assembled a treadway bridge between the villages of Rosny on the southern bank of the Seine and Guernes on the far shore some distance upstream from Mericourt. The bridge was completed that afternoon, and the 315th Infantry Regiment crossed in trucks. By nightfall most of the division, including tanks and artillery, had crossed the Seine, and a secure lodgment had been established on the east bank. The following day the engineers began construction of a Bailey bridge at Mantes, which opened for traffic on the 23rd. As work progressed at Mantes, the Germans launched airstrikes to destroy the structure. These attempts were frustrated by American antiaircraft guns planted around the crossing area.

From August 22-28, the Germans put in six determined ground assaults to eliminate the 79th Division’s bridgehead on the Seine. These were accompanied by numerous bombing and strafing runs carried out by the Luftwaffe. With the failure of their last counterattack, the Germans abandoned their effort to destroy the Mantes bridgehead and fell back to the east.

The American bridgehead across the Seine at Mantes was a major threat to the Germans as U.S. armored forces could then easily break out and race northward behind those units trying to recover east of the Seine. But there was also a threat to German forces still west of the Seine. This was posed by an American plan settled on August 19 to attack to the north along the west bank of the Eure River (25 kilometers west of Mantes) to cut the German escape routes leading to the Seine crossings between Vernon and Pont de l’Arche above Mantes.

The attempt to encircle enemy forces between Argentan and the lower Seine was to be made by the XIX Corps, part of Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ U.S. First Army, and Third Army’s XV Corps. Both were to attack to the north along the Eure, XIX Corps on the left of the river heading to Elbeuf (30 kilometers from Mantes) with the 2nd Armored and 30th Infantry Divisions and the XV Corps’ 5th Armored Division on the right driving for Louviers, 20 kilometers from Mantes.

On August 20, XIX Corps commenced its attack with its 2nd Armored Division on the left of the corps’ advance and the 30th Infantry to the right. The 28th Infantry Division followed to the left rear to protect the corps’ west flank. Despite heavy rain, deep mud, and poor visibility, Maj. Gen. Edward H. Brooks’s 2nd Armored rapidly maneuvered toward the Seine, leaving any enemy pockets of resistance to be dealt with by the 28th Infantry. Opposition to the 2nd Armored Division’s advance, in the form of the German 17th Field Division and 331st Infantry Division, quickly melted away. On August 24, 2nd Armored entered the outskirts of Elbeuf and encountered determined resistance from a German kampfgruppe tasked with protecting the Seine crossings farther downstream. On the 23rd, the 30th Infantry occupied Evreux, and two days later the 30th took Louviers, which had been abandoned by the enemy.

That same day, Combat Command A, 2nd Armored Division, under Colonel John H. Collier, and the 28th Infantry Division attacked Elbeuf. The German force there crossed to the east of the Seine that night, allowing the Americans to secure the town the following day without a fight. On the 26th, Louviers and Elbeuf were handed over to Canadian troops, and XIX Corps starting moving south. Recalling a previous situation when the British had claimed they had captured the town of Vire when it had really been taken by the Americans, General Brooks ordered Colonel Collier to get a receipt for Elbeuf before turning the town over to the Canadian First Army! Said document was duly provided by Major J. Stevens of the Canadian 7th Infantry Brigade. All who witnessed the transfer noted that the Canadians were not amused by the requirement.

The XV Corps also initiated an attack on August 20, but immediately after jumping off from its starting point northwest of Mantes the 5th Armored Division ran into strong opposition from a hastily assembled German battle group with the job of covering the Seine crossings downstream from Mantes between Elbeuf and Louviers. The German defenders fought skillfully using the wooded and hilly terrain to good advantage. In addition, several days of rain and fog prevented American airpower from coming into play. In the face of this enemy resistance, it took 5th Armored five days to accomplish its mission to advance 30 kilometers. In the end, the German force, after shepherding thousands of its comrades across the river, was able to disengage and cross to the east side of the Seine on the night of August 25.

On August 24, XXX Corps, British Second Army, entered the American sector just north of Mantes. For the next several days XV Corps handed over this western portion of the Seine line to the British before the Americans withdrew southward just below Dreux. That town became the boundary line between Montgomery’s 21st Army Group and Bradley’s 12th Army Group.

The envelopment of the Germans on the lower Seine had failed to achieve the success the Allies had hoped for. However, German opposition along the west bank ended on August 29 as the last of the escapees crossed the river. Regardless of the terrible situation they had found themselves in, the Germans had managed to get a surprisingly large number of men and amount of equipment across the Seine in the face of Allied pressure. This included 12 divisions (six infantry, five panzer, and one parachute) that had escaped the Falaise Pocket, plus the remnants of numerous divisions that had ceased to exist. In addition, 11 other divisions that had not been involved in the pocket also reached the Seine ahead of the Allies.

A survey conducted by the RAF Bombing Analysis Unit concluded that more than 95 percent of the personnel who reached the Seine had succeeded in crossing. Of motor vehicles (other than tanks) the figure was 90 percent; the figure for armored fighting vehicles was 75 percent. In all, 240,000 men had gotten across along with more than 30,000 vehicles of all types, including 150 tanks. German officers attributed this achievement to the fact that the British and Canadian armies had not pushed ahead as aggressively as they should have. Further, the Allied air forces had not been active over the Seine region during these critical days so that German ferry and bridge traffic had been able to operate even during daylight hours.

On August 21, after securing much needed supplies from newly established depots at Le Mans, Patton’s XX and XII Corps advanced eastward. The former set out from Dreux and Chartres, while the latter moved from Orleans. Both formations were aiming for the upper reaches of the Seine south of Paris. As for the enemy, the German First Army, which was holding this sector of the Seine, was trying to assemble enough men to defend the river. Beside small and poorly equipped elements of the 48th and 338th Infantry Divisions, this force included security troops, local town garrisons, antiaircraft detachments, and stragglers.

On the XX Corps’ right flank, the 5th Infantry Division advanced with two regiments abreast on August 21. The 10th Infantry Regiment on the right overcame unexpectedly strong opposition and passed over the Essonne River. But on the left, the 2nd Infantry Regiment became entangled in a battle with the enemy at the town of Etampes. Maj. Gen. Stafford Leroy Irwin, commander of the 5th Division, decided to commit his reserve force, the 11th Infantry Regiment. The 11th skirted the city to the south and crossed the Essonne. However, its leading troops met increasing resistance as they advanced toward Fontainbleau 50 kilometers south of Paris. Their progress slowed to fewer than 10 kilometers on the 22nd. However, the following day saw the Germans withdraw, allowing the 11th Infantry to reach the Seine that afternoon.

After a brief battle with portions of the retreating German 48th Infantry Division, the 5th Infantry Division began to cross the river in small boats found lying along the west bank. By August 24, an entire battalion of the 11th Infantry Regiment had paddled across the Seine at Samoreau opposite Fontainbleau. By day’s end division engineers had built a treadway bridge near the original crossing spot, and the entire 11th Regiment was soon east of the river.

In the meantime, the 10th Infantry Regiment had crossed the Loing River at Nemours, which had already been liberated by French resistance fighters. The Americans then cleared the confluence of the Seine and Yonne Rivers at the town of Motereau. That evening engineers brought up assault boats, and a solid bridgehead was established on the right bank of the Seine by the 24th. On the morning of the 25th, with the entire American 10th Regiment over the river, the German 48th Division launched an uncoordinated attack that was easily repelled.

On the XX Corps’ left flank, Maj. Gen. Lindsay Silvester’s 7th Armored Division, with two combat commands side by side, covered 50 kilometers on August 21. Combat Command Reserve (CCR) on the right advanced on Melun, 30 kilometers south of Paris, with plans to seize the Seine bridge located there and secure a crossing at the town while Combat Command A aimed to pass over the Seine north of the town to attack it from the rear. The following morning CCR was just outside Melun and reported that the bridge was still standing and appeared in good condition. Silvester decided to take the Germans by surprise. He ordered the unit to attack at once. However, elements of the German 48th Infantry Division fought back, foiling the American assault. A second attack went in that evening, this time preceded by air attacks and a 20-minute preliminary shelling from three artillery battalions. The result was a repeat of the earlier American failure. The enemy could not be budged.

Just before sunrise on the 23rd, the Germans completed their retreat from Melun, blowing the bridge before the Americans could initiate another attack. General Walker arrived at the CCR command post later in the day. He was far from satisfied with the unit’s recent performance, considering its leadership too hesitant in the face of the enemy, and ordered it to resume the attack immediately. With Walker practically running the operation, CCR armored infantry that afternoon used what remained of the downed bridge to reach the island in the middle of the river. The attackers suffered many losses from the eastern bank due to enemy machine-gun fire, and a stalemate soon developed on this part of the 7th Armored Division’s front.

Meanwhile, held up for a time at the town of Arpajon, CCA reached the Seine at Ponthierry, a dozen kilometers downstream from Melun. Although the bridge at Ponthierry had been destroyed, American infantry were able to cross the Seine in assault boats near Tilly. Divisional engineers worked through the night to construct a treadway span, completing it the following morning. Soon CCA tanks crossed to support the small bridgehead on the east bank. Combat Command B soon followed. While CCA established positions north and east, CCB turned south and drove into Melun, putting an end to that fight on the morning of August 25. That same day, Third Army handed over the Melun bridgehead to the U.S. First Army, the latter’s VII Corps taking over from the former’s XX Corps.

For five days Third Army’s XII Corps had been held at Orleans to conserve fuel and other supplies. Now, on August 20, under its new commander, Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy, it was directed to resume its advance and drive to the town of Sens on the Yonne River. With Combat Command A, 4th Armored Division leading the way, XII Corps rushed eastward on the 21st, bypassing Montargis, which was found to be defended but with its bridges over the Loing River down. After scouting the area, 4th Armor troops discovered a damaged but usable bridge at Souppes-sur-Loing, 25 kilometers north of Montargis. Seizing the opportunity, CCA crossed the river and raced for Sens, encountering only feeble enemy resistance along the way. The vanguard of the 4th Armored entered Sens that afternoon, surprising the unsuspecting German garrison and establishing a bridgehead across the Yonne.

Sizable Nazi forces, including remnants of the 708th Infantry Division and security and supply personnel, were still encamped in Montargis. To clear them out, the 35th Infantry Division was directed to advance to the west of the city while 4th Armored Division’s CCB turned south from Soupes-sur-Loing and outflanked the town from the east. A coordinated attack broke the Germans’ will to fight at Montargis, and the city was in American hands by the end of the 24th. Thereafter, U.S tanks and infantry proceeded to sweep the area eastward to Sens.

From Sens, the 4th Armored’s CCA continued its march to the east on August 25, reaching the city of Troyes that same day. The attack on Troyes was met with tough German resistance. As combat continued in the town, a second U.S. tank/infantry task force moved north of Troyes that same evening. This force hit the town’s garrison from the rear the following morning, effectively ending the battle for the city.

On August 25, 1944, Paris was officially liberated by the French 2nd Armored and U.S. 4th Infantry Divisions after four years of German occupation. Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow moved his V Corps to the French capital and established another bridgehead over the Seine.

As the liberation of Paris wound down, the Allied pursuit of the enemy beyond the Seine River was renewed. While the British and Canadian armies consolidated their crossings of the Seine from Mantes to the English Channel, the Americans solidified their three bridgeheads over the Seine: from north to south controlled by the VII, XV, and V Corps of First Army.

South of Paris, the Third Army, now consisting of XX and XII Corps (XV had reverted to First Army) held two bridgeheads over the Seine: XX Corps’ sites at Samoreau and Montereau, and XII Corps’ single crossing at Troyes.

To flesh out the XII Corps for the drive east to the Meuse River, Patton moved the 80th Infantry Division from Orleans and added it to Eddy’s command. Then 4th Armored Division’s CCB swept the corps area while the 35th Infantry Division protected the right margin from Orleans to Troyes. In the meantime, CCA (4th Armored) sped 80 kilometers and jumped the Marne River at Vitry-le-François. While CCA drove down the east bank of the Marne toward Chalons, the 80th Division moved along the western bank and by noon on August 29 secured Chalons with a double envelopment. By then the XII Corps had run out of fuel but was able to proceed nevertheless at a slower pace after capturing 100,000 gallons of German gasoline at Chalons. On the morning of the 31st, a scouting company from CCA, moving under the cover of heavy rain, surprised the German guard at the bridge in the town of Commercy and seized the structure intact.

With the 90th Infantry Division added to its rolls, the XX Corps attacked from Mulan with the 7th Armored Division leading the way. The American tankers encountered scattered elements of the German 48th and 338th Divisions as well as tanks from the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division. Attacking from the Montereau area on the 26th, the 5th Infantry Division met somewhat lighter opposition and took Nogent-sur-Seine and the town of Romilly. The 5th Division then captured Provins.

As the 5th Infantry plodded on, General Walker ordered the 7th Armored to thrust northwest toward the city of Reims. With the 5th Infantry Division following on the right and the 90th on the left, the 7th Armored spearheaded the attack. On the 28th, with two combat commands abreast, no less than six columns were driving ahead in hopes of grabbing one or two bridges over the Marne intact. Since only small pockets of enemy resistance were met, CCA and CCR jumped ahead to Chateau-Thierry and captured several bridges over the Marne. Continuing on to the Aisne River, on the 29th the two combat commands wheeled to the east and cut the roads north of Reims. The 5th Infantry entered the town the next day. By noon on August 31, the 7th Armored Division had reached Verdun and was across the Meuse.

On August 25, First Army’s VII Corps, Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins commanding, started its move from the Melun bridgehead with the 3rd Armored Division pushing to the northeast, breaking the German LVIII Panzer Corps’ defense line. The next day the hard-charging 3rd Armored reached and crossed the Marne at La Fertee and Meaux. The 1st and 9th Infan-try Divisions closely followed. The Aisne was crossed around Soissons on August 28. Three days later, leading elements of 3rd Armored were at Rethel and Montcornet.

Having completed the liberation of Paris, the V Corps joined the pursuit of the Germans east of the Seine on August 29. On the 31st, the 5th Armored Division, after overtaking the 4th and 28th Infantry Divisions, drove through the Compiegne Forest. However, strong enemy opposition combined with close terrain forced General Gerow to use the 4th Infantry Division to clear the forest. On September 1, the vanguard of the corps crossed the Aisne River between Compiegne and Soissons.

On August 27, the 30th Infantry Division traveled over the Seine into the Mantes bridgehead, as did the 2nd Armored Division the next day. The 79th and 30th Divisions then began to expand their hold on the east bank of the Seine.

On August 29, the XIX Corps (2nd Armored, 30th and 79th Infantry Divisions) pushed 80 kilometers northeast against little enemy opposition and reached a line between Beauvais and Compiegne.

The concerted Allied effort to cross the Seine had been successfully accomplished by late August 1944 along a 350-kilometer front from Rouen to the south of Paris. They had, however, failed to destroy the German forces west of the river, and a surprising number of the enemy had succeeded in extricating themselves. Regardless, few if any of the German formations that escaped east of the Seine were in condition to continue the fight.

Instead of pausing at the Seine to regroup and resupply, as had been first planned, the Allied armies had quickly crossed the river and kept on going. The Germans had been unable to form a cohesive battle line, and whatever effective German resistance was offered had been, to a large extent, the product of individual initiative at lower command echelons. The Allied drive reached its high point during the first 10 days of September. On the 11th a patrol from the 5th Armored Division, V Corps, crossed into Germany. By that day, D+97, the Allied armies arrived at the general line that preinvasion planners had expected would not be gained until D+330. Most of that distance had been covered in the previous 48 days, an astounding achievement by any standard.

Arnold Blumberg is an attorney with the Maryland state government and resides with his wife in Baltimore County, Maryland.