By Blaine Taylor

At 8 am on the cold, blustery morning of November 7, 1941, the 24th anniversary of the Russian Communist Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, a dashing lone horseman galloped out of the Spassky Gate of the Kremlin onto snow-covered Red Square. Inspecting the assembled troops waiting to go directly to the front to halt the advancing German Army in its relentless march on the capital, Marshal of the Soviet Union Semyon Mikhailovich Budenny (also spelled Budyonny) received their acclamations of “Hurrah!” then spurred his horse to the base of the Lenin Mausoleum, dismounted, and strode up the steps to join his master, dictator Josef Stalin.

“A Man Without Pretensions”

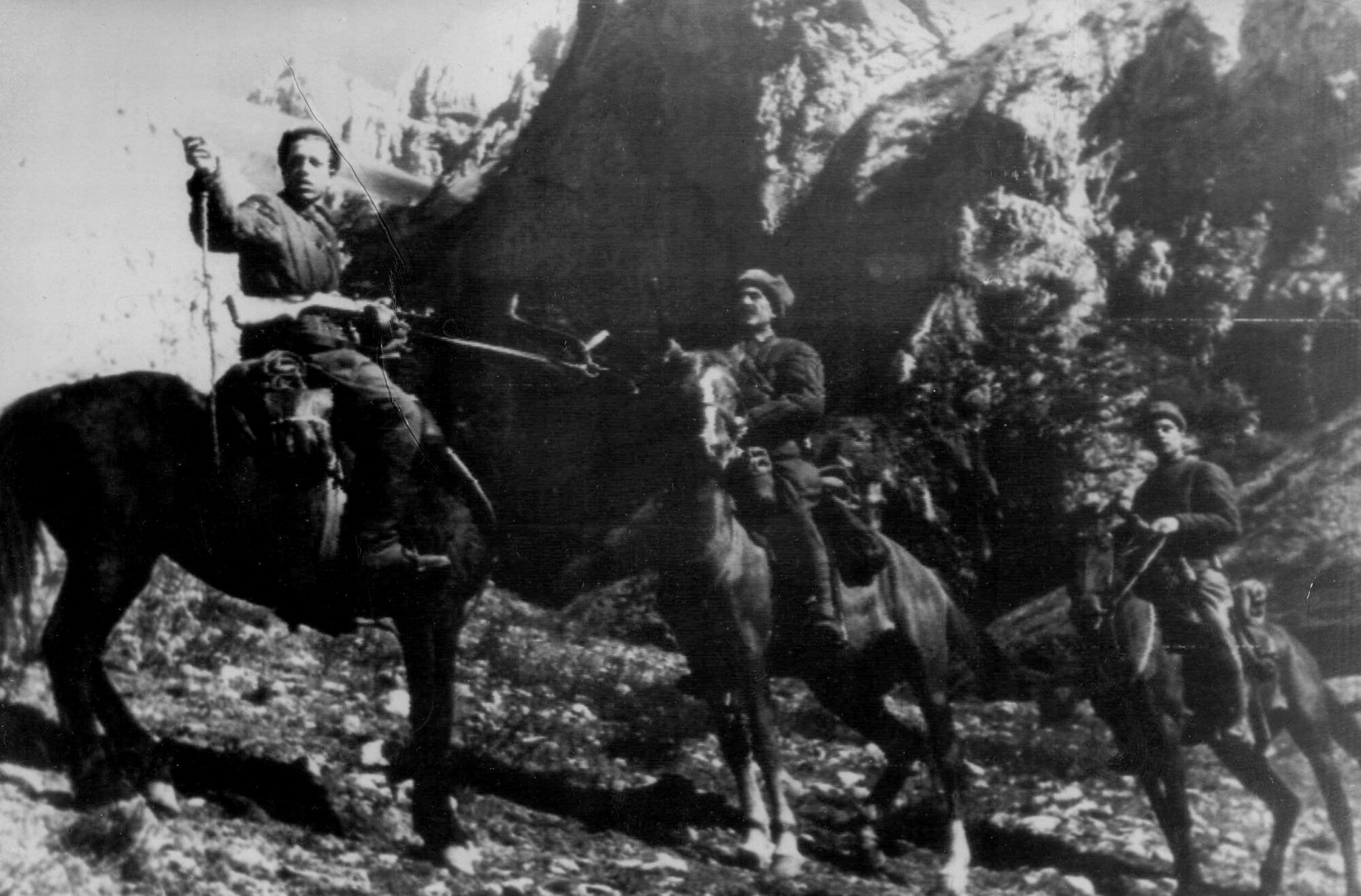

The legendary commander of the Red Cavalry during the Russian Civil War of 1918-1920 against the defeated White armies of the fallen Tsar Nicholas II, the colorful, swashbuckling, walrus-moustached Budenny was a sort of latter day Prussian Marshal Gebhard von Blucher, whom he strongly resembled in character.

Wearing a Sam Browne belt over his ground- length greatcoat and the peculiar pixie-type cap that he had popularized, Budenny on his horse at the head of thousands of charging steeds crashing over the steppes of Mother Russia seemed to be the very embodiment of the renowned Soviet cavalry, sweeping all aside with the fury of their thundering hooves. Indeed, this was the actuality until the mechanized warfare of the summer and fall of 1941 put Budenny and his cavalry into partial eclipse, seemingly for good.

As with any controversial wartime commander, later opinions and views of Budenny were mixed, but always spirited. Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav M. Molotov stated in his 1991 memoirs, “Budenny’s conduct was praiseworthy, but at the same time one could not demand too much of him. He was meritorious and popular with the people.”

Soviet military writer Viktor Anfilov characterized Budenny as “a patriot, brave man, talented military leader of the Civil War and a national hero. He had a long record of indiscipline, was ignorant and limited, a man without pretensions.”

Budenny, a former tsarist cavalry sergeant major, was both dashing and a heavy drinker, to which he added a liberal dose of incompetence, character traits common to many soldier leaders both then and now. The holder of the Order of Suvorov 1st Class and three times a declared Hero of the Soviet Union, Budenny was 62 in 1945 at the end of the Great Patriotic War (the Russian name for World War II). He went on to become deputy minister of agriculture in the postwar Soviet Union. A later foe who knew him in Moscow during 1931-1932, German Field Marshal Erich von Manstein, described Budenny as “entirely natural and uninhibited in his coarseness.”

Budenny’s former subordinate and later commander, Marshal Georgi Zhukov, said of his one-time boss that he was “hot tempered, but always objective. I gave him assignments that he always carried out in good faith.” Their colleague Marshal Ivan Konev was much more harsh, however, calling Budenny “a man with a past, but no future. He never knew much and never studied anything.”

Devotion to the Bolsheviks

What Budenny did know, however, was how to be slavishly loyal and utterly devoted to Generalissimo Stalin, to carry out his orders ruthlessly, and to inspire others to do the same. Arriving at one embattled position during the German onslaught of 1941, Budenny yelled, “We shouldn’t be defending ourselves, but defeating the enemy! We’re a strong fist!” During another tense encounter, Budenny screamed at fellow marshal Ivan K. Bagramyan, “I think we’d better have you shot!”

According to Anfilov, the man who was a serving soldier to both the tsar and Stalin had “beaten the best of the White cavalry” as commander of the lst Cavalry Corps of the Red Army during the Civil War, and his renowned “cavalry army” was “ready to follow wherever Budenny led.”

Marshal Budenny rose to become the preeminent horse specialist in the Soviet Union, and even Stalin deferred to him in all things equestrian. In September 1923, he appointed Budenny deputy commander in chief of Cavalry Forces, then later to the top post of Inspector of Cavalry. Six years afterward, Stalin even went so far as to proclaim, “Aircraft will not replace the cavalry” for reconnaissance purposes as a further sop to Budenny’s vanity. This concept was one of the first mistakes that led to the mammoth defeats of 1941 at the hands of the Germans.

Budenny’s fame hit its peak on November 20, 1935, when Stalin made him one of the first five marshals of the Soviet Union. His appointment led little boys playing in the streets to boast proudly that they were “Budenny’s men.” The bedrock of both his moral authority within the Red Army and his ability to survive the defeats of 1941 was Stalin, whom he served “body and soul,” and who in turn honored the marshal by seeing him “privately and individually in his own office,” according to Anfilov. Time and again throughout his long career, no matter what the generalissimo would order him to do, Budenny would snap to attention and answer, “Comrade Stalin, my task is clear!” and then proceed.

The cavalry marshal’s loyalty to Stalin continued long after his death, as reflected in his memoirs, which were published in 1968. He never forgot that his superior would turn to him and say in the middle of conferences, “You are the most competent man in this matter. Let me have your proposals.”

He was also loyal to other old Bolsheviks after their fall, as noted by Molotov in a 1978 interview: “Despite my expulsion from the Party, Budenny would always send me greetings on national holidays. His handwriting grew shaky, and yet he would keep mailing me his postcards.”

“My Job is to Serve”

Budenny was born into a peasant farm family on April 25, 1883, near Platovskaya on the Don River and was drafted for military service at age 20 in 1903, serving in the Russo-Japanese War in the 46th Dragoon Regiment. A courageous horseman who was wounded, he nevertheless remained with his unit until the end of the war. When he was asked if he had heard about the uprising in St. Petersburg against “our little father, the Tsar” as a result of discontent with the war with far-off Japan, Budenny answered, “How could I not, your excellency? Nobody talks about anything else!” Asked his opinion of it, the young dragoon replied, “My job is to serve.”

Unlike many others who deserted the Tsar to join the revolution, Budenny remained true to the colors until they were replaced by the Red banner of the Bolsheviks, then he served them until his death. Thus, the marshal was an apolitical soldier of the state.

Having completed the St. Petersburg Cavalry School in 1907, Budenny was promoted to sergeant, serving with a platoon in the Caucasus Cavalry Division from September 1914 to October 1917. He was awarded four St. George Crosses and the full ribbon of a St. George Cavalryman, the highest decoration he could receive.

After World War I ended and the Germans worked with the White forces at the start of the Civil War, he joined the Reds and served as the brigadier in command of Special Cavalry Division Budenny in the Tenth Army under his later fellow marshal, Kliment Y. Voroshilov. He also won his first Order of the Red Banner and was soon signing a letter to none other than Vladimir I. Lenin as “Cavalry Corps Commander Budenny.” Such a meteoric military ascent in the span of a few years is exceptional.

On November 17, 1919, Budenny was named commander of the First Cavalry Army of the Soviet Army. Stated Anfilov, “In maneuverability and speed of attack, the Cavalry Army had no equal, and according to former German Chief of Staff Gen. (Franz) Halder, its experience was not lost on the Wehrmacht.” Transferred to the Caucasus, Budenny there began a tendency not to follow the orders of his immediate superiors if he disagreed with them. In addition, Budenny, the former sergeant of the 18th Seversky Dragoons, and Voroshilov have been accused by later writers of being responsible for “cruelty and atrocities” against captured White prisoners of war. Both he and Voroshilov began taking their complaints directly to Stalin, whom Budenny first met in July 1918.

Nor was Budenny always victorious, having been beaten in battles by both the Cossacks and the Poles, two peoples who also boasted some of the finest cavalrymen on earth. In August 1920, he also found himself at odds with Stalin’s fiercest rival, Red Army organizer Leon Trotsky. Another man who served under Budenny during the Civil War in 1919 was Nikita S. Khrushchev, Stalin’s ultimate successor in the mid-1950s.

Unprepared for War with Germany

In July 1967, Budenny wrote, “There wasn’t a single small child who didn’t believe that the Germans were getting ready to attack” the Soviet Union in the spring of 1941, and yet, apparently, Stalin himself was not one of them, asserting to the end that Hitler would never break the Nazi-Soviet nonaggression pact signed in Moscow in August 1939.

The Soviet Union found itself badly prepared for the onset of mechanized warfare, a situation that dated back to Budenny’s insistence as early as 1920 for cavalry instead of the tanks and planes for which Trotsky and others were clamoring. Even after the Cavalry Army was officially disbanded after the Civil War, some divisions were still kept up to strength at his command.

On June 6, 1937, Marshal Budenny was named head of the Moscow Military District. In March 1940 he was severely criticized for the way his troops had conducted themselves during the defeats of the Russo-Finnish War. Still, he refused to change, as evidenced during a military exercise conducted in July 1940 by the new commissar of defense, Marshal Semyon K. Timoshenko, a former divisional commander in Budenny’s Cavalry Army.

To direct a tank attack himself, Marshal Budenny leaped onto the lead tank, causing his driver to panic and almost land the vehicle into a ravine full of water. Timoshenko, who had witnessed the scene, admonished his fellow marshal, “I wouldn’t advise you to sit on a tank, but rather at the command post where you can control your forces. In the Civil War we used to gallop after you with our sabers drawn, but those days are long gone, and a tank is not a horse!”

Two Pieces of Advice

Stalin removed his crony as Moscow District Commander and reposted Budenny as deputy defense commissar under Timoshenko, leading the old warhorse to admit sheepishly to his staff, “It is we, the senior officers, who need to study” and thus change. It was in this new capacity that he gave Stalin two pieces of advice —one good and the other fatal—at a council of war the very day before the German invasion of June 22, 1941.

The first was that the ropes that normally tied Red Air Force planes to the ground should be taken off so that they would be on alert in case of attack. The second was to get all troops moving toward the front so that they would be in place no matter what the future enemy did. This had the effect of putting thousands of Red Army men on roads and railways where they could be attacked by the Luftwaffe. Nine hours before the great attack, Marshal Budenny found himself a member of STAVKA (the Supreme Command), with Political Commissar Georgi Malenkov as his joint commander but without any staff, troops, or equipment.

From July to September 1941, Marshal Budenny was in command at Kiev, the capital of Ukraine, and later at Kharkov, with Khrushchev as his political commissar. Their main tasks were to hold the cities while evacuating industrial machinery. Seeing plainly that they were going to be encircled by the Germans, the old cavalryman urged Stalin to allow a retreat, but Stalin forbade it. As a result, on September 21, a staggering 665,000 Red Army soldiers were lost as prisoners to the Germans, a catastrophe that some writers have since blamed on Budenny.

Stalin had relieved Budenny on the 11th, however, and rather than shooting the old horseman, placed him in command of the Reserve and West Fronts where, on October 6 at Vyasma, both he and Marshal Voroshilov lost a combined total of 45 Red Army divisions and 673,000 prisoners to a second German encirclement. Two days later, Budenny was fired once again, but he was not shot.

Budenny Leads the Cavalry Once More

On May 10, 1942, Stalin sent Budenny to the Crimea, and the following July Budenny took over the North Caucasus Front from the relieved General Rodion K. Malinovksy. Upon returning to Moscow, Budenny ran into Marshal Zhukov who told him in January 1943, “No doubt you’re going to have to lead the cavalry again.” That spring, after Stalingrad, the marshal was named commander of the Red Army Cavalry once more. Restored to his favorite wartime role, the crusty marshal created “mounted armored groups” and provided aerial cover for his beloved horsemen.

Marshal Semyon Mikhailovich Budenny died at age 90 on October 26, 1973, and was buried with full military honors in the Kremlin Wall beside his revered former leader, Josef Stalin.

Towson, Maryland, freelancer Blaine Taylor is the author of several books on World War II, including Volkswagen Military Vehicles of the Third Reich and Apex of Glory: Mercedes and Daimler-Benz in the Third Reich.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments