By Mason B. Webb

Iwo Jima was one of the toughest battles of World War II, and three new books provide perhaps the definitive word on that epic, month-long struggle in February and March 1945.

The first (and biggest) of the three is Iwo Jima: Portrait of a Battle, by Eric Hammel (Zenith Press, St. Paul, Minn., 2006, $40.00). Within its 255 oversized pages the reader will find more than 500 photographs—most likely the bulk of all the photos taken before, during, and after the battle—including a section of color photographs showing the island as it appears today.

The first (and biggest) of the three is Iwo Jima: Portrait of a Battle, by Eric Hammel (Zenith Press, St. Paul, Minn., 2006, $40.00). Within its 255 oversized pages the reader will find more than 500 photographs—most likely the bulk of all the photos taken before, during, and after the battle—including a section of color photographs showing the island as it appears today.

Many of the combat pictures have never been published before, probably because so many are unblinking shots of the dead on both sides.

Hammel says, “Even in as bloody and bluntly violent war as Americans encountered in the Pacific, Iwo Jima was the ultimate expression of death and mayhem. It was in a class by itself, a meatgrinder smashed by a blunt instrument at an extremely high cost.”

Indeed, Iwo Jima became the killing ground for 6,821 American Marines, nearly 900 U.S. sailors, and 20,000 Japanese; another 19,217 U.S. servicemen were wounded on the island. Only a little more than a thousand Japanese survived to be taken prisoner, an indication of the value Japan placed on holding the island. Once secured, Iwo Jima—“Sulfur Island”—became a critical air base for the Americans in their campaign to bomb Japan into submission.

The net effect of the text and photographs in Hammel’s book is to give the reader a sobering sense of the sheer courage it took to defeat a fanatical enemy that had no hope of either escape or victory—a visually stunning work.

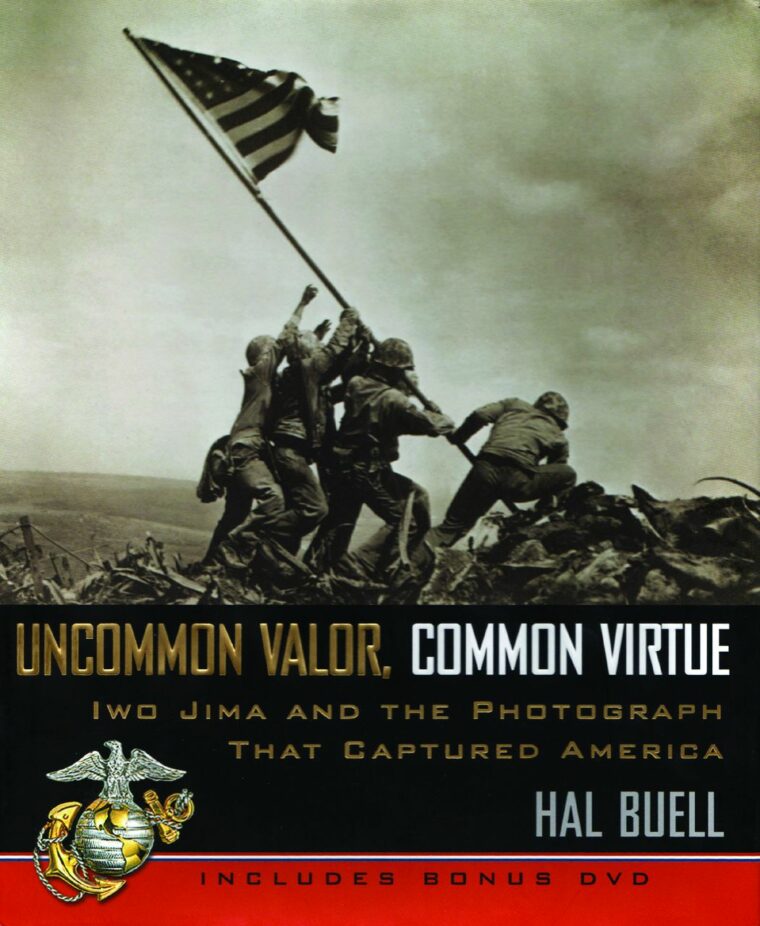

The companion book to Hammel’s, if one chooses to call it that, is Hal Buell’s Uncommon Valor, Common Virtue: Iwo Jima and the Photograph That Captured America (Berkley/Caliber, New York, 2006, 272 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, $28.95).

This is basically a book about Joe Rosenthal and six other combat cameramen who documented, almost by accident, the raising of the flag on 556-foot-high Mount Suribachi. Rosenthal’s iconic, Pulitzer-winning image is arguably the most famous photo taken during World War II, and the same may be said of the motion-picture film shot by Marine Sergeant Bill Genaust.

Buell, who spent more than 40 years as a photo editor for the Associated Press, goes into considerable detail about the lives (sometimes brief) of combat photographers, and Rosenthal’s life in particular. Much of the narrative is provided by the photographers themselves, talking about how their pictures came to be taken.

But the book is also much more than that. Uncommon Valor, Common Virtue is a grunt’s-eye view of the savage fight, a full account of the battle with more than 120 photos, including shots of the flag-raising taken by other photographers, quotes from veterans, newspapers, and magazines, and official battle reports.

Buell’s book includes a chapter on the myths that have grown up over the decades, including the widely held belief that Rosenthal’s photo was somehow staged or faked. It also contains, as a bonus, a 20-minute-long DVD that interweaves combat footage with interviews with Marine veterans.

Both Hammel’s and Buell’s books contain the citations for the 17 Americans who were awarded the Medal of Honor, some posthumously, for their courageous actions at Iwo Jima. As Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, commander of U.S. Navy forces in the Pacific, once so succinctly put it, “Of the Marines on Iwo Jima, uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

As long as we are on the topic of Iwo Jima and valor, there is a third book that must not be overlooked. Indestructible: The Unforgettable Story of a Marine Hero at the Battle of Iwo Jima (DaCapo, Cambridge, Mass., 2006, 212 pp., $22.95) is the autobiography of Jack H. Lucas, the youngest Medal of Honor recipient of the 20th century. And it is one of the most remarkable true stories one is ever likely to read.

As long as we are on the topic of Iwo Jima and valor, there is a third book that must not be overlooked. Indestructible: The Unforgettable Story of a Marine Hero at the Battle of Iwo Jima (DaCapo, Cambridge, Mass., 2006, 212 pp., $22.95) is the autobiography of Jack H. Lucas, the youngest Medal of Honor recipient of the 20th century. And it is one of the most remarkable true stories one is ever likely to read.

Lucas, full of anger about Pearl Harbor, was too young to join the military but lied about his age and enlisted in the Marines in August 1942 at age 14. Assigned to stateside duty, he went AWOL and stowed away on a troop transport heading across the Pacific. As a member of the 5th Marine Division, he was under fire from the moment his landing craft approached Iwo Jima until he was badly wounded.

As Lucas and his three buddies were assaulting an enemy position on D+1, two live Japanese grenades landed at their feet. He writes, “All four of us were actively engaged with the enemy. No one noticed the two grenades drop into the trench in front of Crowson, the BAR man. I would have missed them myself had I not been looking downward as I struggled to un-jam my rifle. That is the moment they first caught my eye. Lying at our feet, weighing one pound, less than four inches in length, and with only four seconds of fuse, were the implements of almost certain death. How long had they been there? How much time was left? I yelled ‘Grenade!’ to alert my buddies and pushed my BAR man out of the way.”

Instinctively, Lucas threw himself on top of the grenades and was torn to shreds and knocked unconscious when one exploded (miraculously, the other was a dud). His buddies were not hurt. Left for dead, Lucas somehow caught the attention of a medical corpsman who evacuated the youngster to a waiting hospital ship. Navy doctors, despite believing he had no chance of survival, worked to save his life; they did.

When the Navy learned of Lucas’s courageous act, he was recommended for the nation’s highest military decoration; he received it from President Harry S. Truman in October 1945.

But that’s not the end of this story. After being discharged from the Marines, he completed his education, earned a college degree from Duke University, and then, missing the military life, enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1961, becoming an officer in the elite 82nd Airborne Division!

Recent & Recommended

Appeasement & Rearmament: Britain 1936-1939 by James P. Levy, Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham, Md., 2006, 189 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, $27.50, softcover.

Appeasement & Rearmament: Britain 1936-1939 by James P. Levy, Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham, Md., 2006, 189 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, $27.50, softcover.

The conventional wisdom is that Neville Chamberlain, Britain’s prime minister from 1937-1940, seeking at all costs to avoid war with Germany in the late 1930s, bent over backward to appease Adolf Hitler.

Who can forget the newsreel image of Chamberlain waving the piece of paper that he and Hitler and the French had signed at Munich, allowing the German dictator to take over the Sudetenland portion of Czechoslovakia, and declaring that the delegations had hammered out an agreement that meant “peace in our time”?

Politicians ever since have used the word “appeasement” as a pejorative term, meaning to meekly give in rather than to strongly confront an opponent.

James P. Levy, a professor at Hofstra University, takes a fresh look at Britain’s dilemma and presents a cogent examination of Chamberlain’s foreign policy and Britain’s domestic condition. As the former Chancellor of the Exchequer, Chamberlain was painfully aware of the fact that his nation had not yet recovered—either financially or materially—from the ruinous cost of victory in the Great War. Seeking to delay for as long as possible a military confrontation with Europe’s emerging superpower, Chamberlain bought time for Britain, time his nation needed to rebuild her armed forces and prepare to weather the storm he saw looming on the horizon.

As Levy writes, “In hindsight, it cannot be denied that Munich was a diplomatic fiasco. Its popularity at the time is understandable, but that does not change the fact that the Allies were pushed around and the Czechs rolled over and played dead. But was it a failure?”

“No,” says Levy, and lays out his argument logically and clearly. This is an intelligent book that casts a cold light on the myriad reasons why countries avoid war while, simultaneously, preparing for it. A definite “must-read.”

The Warlord and the Renegade: The Story of Hermann and Albert Goering by James Wyllie, Sutton Publishing, Thrupp, UK, 2006, 248 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, $29.95, hardcover.

The Warlord and the Renegade: The Story of Hermann and Albert Goering by James Wyllie, Sutton Publishing, Thrupp, UK, 2006, 248 pp., photographs, index, bibliography, $29.95, hardcover.

The world, it seems, knows who Hermann Goering was. His brother, Albert, is less well known, a fact that will change with the publication of James Wyllie’s book about the Nazi Reichsmarschal’s younger sibling.

Albert hated the Nazi regime and spent nearly a decade working against it, using whatever influence he had, intervening whenever possible to rescue victims of Hitler’s hatred, running escape routes, freeing people from death camps, influencing policy, promoting sabotage, and helping the resistance—sometimes right under the noses of Nazi Party bigwigs. One family Albert helped was the composer Franz Lehar, whose light operas Hitler enjoyed, and his Jewish wife, Sophie Pashkis. Because of the marriage, Lehar’s career was about to come to a government-mandated halt when Albert obtained from Josef Goebbels a certificate declaring Sophie an “honorary Aryan.” Wyllie also documents the many instances when Albert, at the risk of his own safety, assisted scores of concentration camp and death camp inmates to escape their fates.

Taken into custody after the war by the Americans on suspicion that anyone named Goering had to be a hardcore Nazi, Albert managed to convince his prosecutors that he had aided the Allied cause; he was eventually freed.

As Wyllie concludes, “Albert [Goering] deserves to stand alongside Raoul Wallenberg and Oskar Schindler” as one of those who stood up against tyranny.

The Warlord and the Renegade deserves to be on every history buff’s bookshelf.

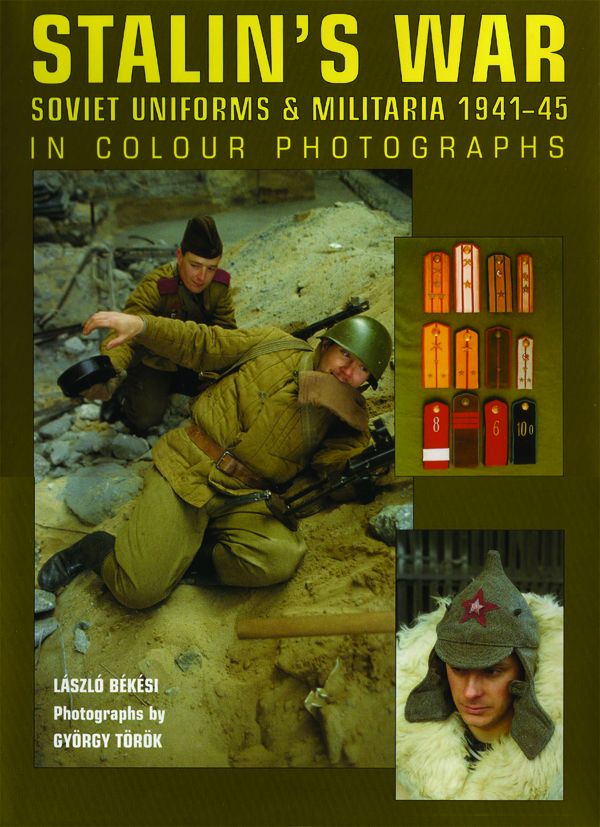

Stalin’s War: Soviet Uniforms & Militaria 1941-45 in Colour Photographs by László Békési, Crowood Press, Ramsbury, UK, 2006, 144 pp., photographs, illustrations, $44.95, hardcover.

Stalin’s War: Soviet Uniforms & Militaria 1941-45 in Colour Photographs by László Békési, Crowood Press, Ramsbury, UK, 2006, 144 pp., photographs, illustrations, $44.95, hardcover.

Stalin’s War is the third volume of Békési’s series on Soviet uniforms and artifacts, and a handsome volume it is! Sixty black and white period photographs are complemented by 230 recent color photos (staged using reenactors in realistic settings) by György Török.

This lavishly illustrated book, along with well-written text and captions by the preeminent expert in the field, gives a detailed look at what the typical Soviet soldier, tanker, airman, and sailor (and even female troops) carried, wore, and fought with.

Stalin’s War is an invaluable reference book for collectors of Soviet gear, reenactors, and anyone interested in the uniforms, equipment, weapons, badges, documentation, and other military and personal accoutrements of the West’s Russian ally.

Cracking the Luftwaffe Codes: The Secrets of Bletchley Park by Gwen Watkins, Greenhill Books, London, UK, 2006, 230 pp., photographs, illustrations, $34.95, hardcover.

Cracking the Luftwaffe Codes: The Secrets of Bletchley Park by Gwen Watkins, Greenhill Books, London, UK, 2006, 230 pp., photographs, illustrations, $34.95, hardcover.

Written by a member of the cryptographic staff at the British codebreaking center at Bletchley Park, this eminently fascinating inside story is an account of the many diverse personalities involved in the complex, highly classified operation and the invaluable service they performed for the Allies. It was not until 1974 that Bletchley Park’s activities were even detailed for the public.

The author, then a sergeant in the British Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, brings to life the reality of the German Air Section at BP, as the center was known, the first-ever account of this crucial department. In a highly informative and lyrical account, she details her eventful interview, her eventual appointment at the “biggest lunatic asylum in Britain,” methods employed to crack the maddeningly difficult codes, the day-to-day operations at the center, and the decommissioning of her section at war’s end.

Cracking the Luftwaffe Code is much more readable than Leo Marks’s Between Silk and Cyanide, which told basically the same story, but not as well. Watkins’ tale is thoroughly enjoyable from start to finish.

Eleven Days in December: Christmas at the Bulge, 1944 by Stanley Weintraub, Free Press, New York, 2006, 220 pp., photographs, maps, $25.00, hardcover.

Eleven Days in December: Christmas at the Bulge, 1944 by Stanley Weintraub, Free Press, New York, 2006, 220 pp., photographs, maps, $25.00, hardcover.

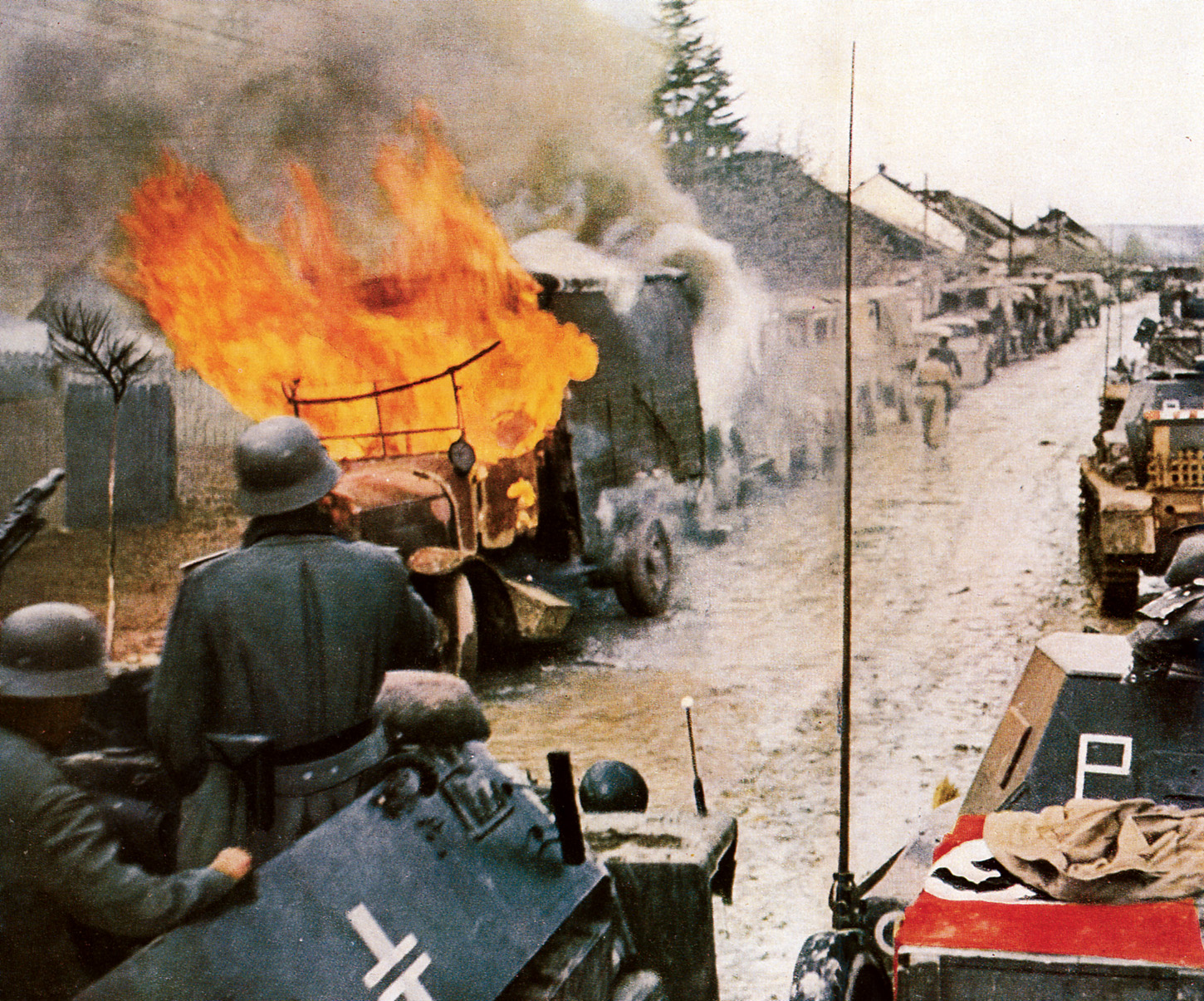

Although weary from six months of slugging their way across Europe in 1944, the American and British armies believed that victory was in sight. The confident Allies, therefore, were unprepared for Hitler’s massive, last-gasp offensive in the West.

After the secret buildup of troops, tanks, and artillery pieces beneath the towering pines of the Schnee Eifel along the German-Belgian-Luxembourg border, Hitler’s forces, nearly 300,000 men strong, punched through the thin olive-drab line and threatened to split the British and American armies and drive all the way to the port city of Antwerp, inflicting such heavy casualties along the way that the Allies would be forced to sue for peace.

Weintraub, a prize-winning author and professor of history at Penn State University, has crafted a highly readable account of the near disaster that befell the Americans in the waning weeks of 1944. Masterfully weaving together the stories of generals and ordinary soldiers on both sides, Weintraub recreates the desperate days when victory was very nearly knocked from the grasp of the Allies and only sheer courage and a little bit of luck turned the tide of battle.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments