By Nathan N. Prefer

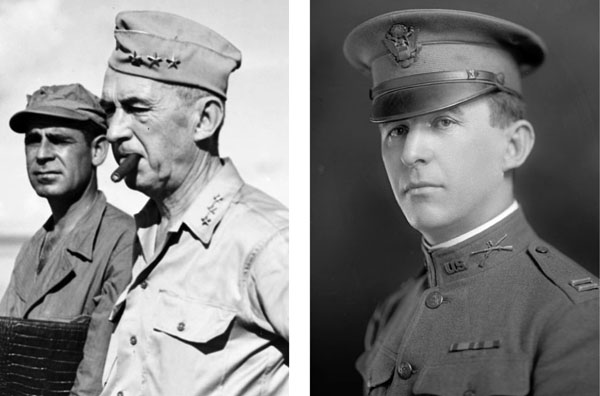

He led the American drive up the New Guinea coast, took his troops ashore on Leyte and Luzon in the Philippines, and was designated by the Allied supreme commander in the Pacific, General Douglas MacArthur, to lead the planned invasion of Japan itself. His picture appeared on the cover of Time magazine and he was referred to as “MacArthur’s Fighting General,” and yet today he is little remembered and rarely honored. General MacArthur, not known for handing out accolades to subordinates, called him “swift and sure in attack, tenacious and determined in defense, modest and restrained in victory.” To the American public he is a “mystery man,” unknown for his many accomplishments. Of all the American Army commanders who fought in World War II, he is the least remembered. His name is General Walter Krueger.

Ironically, General Krueger might have enjoyed more widespread fame had he joined the German Army and fought on the other side. This was indeed a possibility when Walter Krueger was born January 26, 1881, on a large estate in Flatow, Western Prussia (today Zlotow, Poland). His father, Julius, a former Prussian Army officer and veteran of the Franco-Prussian War, had leased the estate for his growing family. But Julius’s sudden death in 1884, four years after Walter was born, forced his mother to move the family to the United States where they lived with her uncle in St. Louis. Soon after their arrival, his mother, Anne Hasse Krueger, met and married a German-born Lutheran minister and the family relocated to Madison, Indiana.

Walter attended local schools and learned to play the piano at home, tutored by his mother. This training imprinted a lifelong appreciation of classical music on young Walter. He also developed a strong sense of discipline and a short temper with what he considered lazy or careless people. By the age of 17, Walter was attending Cincinnati Technical School, preparatory to go on to college for an engineering degree. But that year, 1898, the Spanish-American War began and changed the entire direction of his life. Fascinated by the marching troops and the intense patriotic fervor, he enlisted in the Second Volunteer Infantry Regiment. After training, his unit reached Cuba shortly after the Battle of San Juan Hill. By the time he was mustered out in February 1899, he had achieved the rank of sergeant.

Walter Krueger went back to his studies toward an engineering career, but the military experience had made an indelible impression on him, and by June 1899, barely four months after leaving the military, he enlisted again, this time in the Regular Army’s 12th Infantry Regiment. He soon found himself in action in the Philippines, a locale that would loom large in his future.

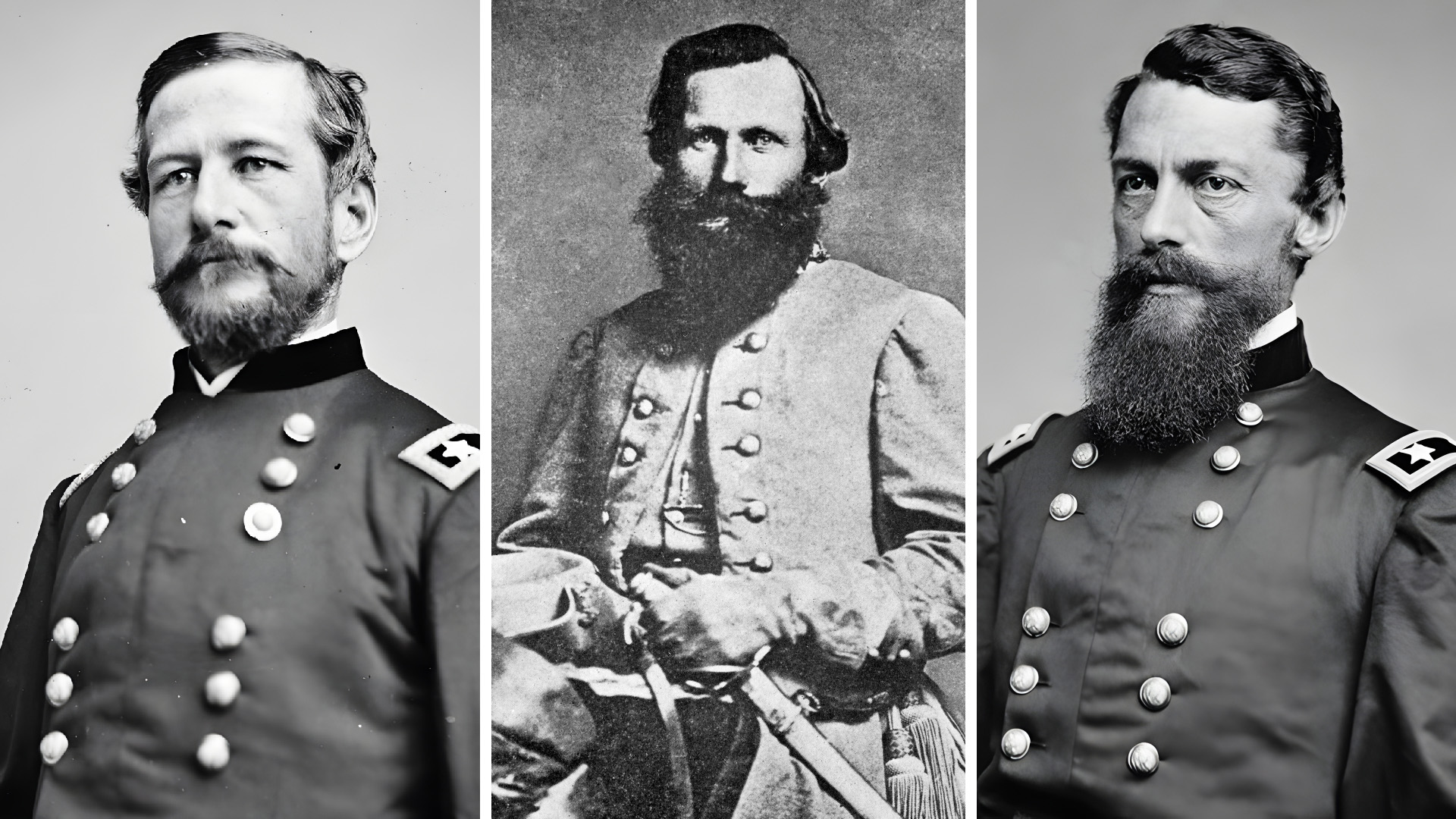

As a private in Company M, 12th Infantry Regiment, he began long chases after the Filipino guerrillas while under the command of former Confederate Cavalry leader, General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler. Krueger’s regiment was a part of General Arthur MacArthur’s 2nd Division, and the fighting covered the central plain of Luzon, where most of the time was spent in isolated garrisons protecting various important posts, railroads, and port facilities. The miserable conditions of the campaign—heat, rain, mud, insects, hunger, thick jungle, and impossible mountains, as well as the many diseases that struck down the average soldier—made a lasting impression on the future general. Later he would remember, “Years ago, in the Philippines, I went without food and other supplies, and I know what it is to be hungry. Then and there I resolved that if I ever had to say-so my men would never be without enough to eat.”

Despite hardships and other difficulties, Sergeant Krueger decided on a military career. Having achieved the rank of sergeant—again—by June 1901, one of his officers asked if he was interested in taking the examination for an officer’s commission in the U.S. Army. Thinking that he had nothing to lose and everything to gain, he took the examination but believed that he had failed miserably. He was most pleasantly surprised when, on July 1, 1901, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant. He was immediately assigned to the 30th Infantry Regiment on the Philippine island of Mindoro.

His experience as an enlisted man in Cuba and the Philippines left Krueger with a deep concern for the men under his command. Years later, while commanding the Third U.S. Army during World War II he remarked to a group of officers, “I have such a high regard for our men that there is something within me [that] turns around when I see they are not being handled right.” Many of those under his command were left with lifelong impressions of a man who was concerned for their welfare, even as he sent them into harm’s way.

One of his duties while in the Philippines was to guard military prisoners on Malahi Island in Laguna de Bay. This was a miserable duty, and the island was a miserable place to live, even without having to deal with the dregs of the Army’s criminal element. But one advantage did accrue for Lieutenant Krueger during his assignment there. One afternoon at Malahi he was serving as the officer of the day when another lieutenant, George C. Marshall, Jr., was the officer of the guard. The Army’s future chief of staff during World War II remembered Lieutenant Krueger. “He is of typical German stock, thorough, hard-working, ambitious, and devoid of humor.” It is possible that this brief working period with future General Marshall favorably influenced Krueger’s later career.

In 1903 he met his future wife, Grace Aileen Norvell, in the Philippines while she was visiting relatives there. And later the 30th Infantry Regiment returned to the United States. At the age of 22, Lieutenant Krueger was well on his way to establishing his reputation as an officer who was devoted to learning as much about his trade as possible, and as a caring and compassionate officer to the men under his command.

Lieutenant Krueger and Grace married in 1904. They would have two sons, both of whom attended West Point and served as Army officers, and a daughter who would marry an Army officer. Also in 1904, Lieutenant Krueger was selected to attend the prestigious Infantry and Cavalry School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Krueger, working hard as usual, graduated with honors and was given a second year at the school’s staff college. He also received a promotion to first lieutenant.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, temporary Major Krueger was assigned to the Bureau of Military Affairs, working on turning citizens into soldiers. After several months, he was transferred to the newly formed 84th Division and later transferred to the 26th Division, a New England National Guard formation already in France. He served as the operations officer for the veteran division and was given a temporary promotion to lieutenant colonel.

Colonel Krueger moved with his division to Chateau-Thierry, where it was to participate in the coming Aisne-Marne offensive. But problems with the French allies, who distrusted Colonel Krueger because of his German heritage, forced his return to the States and the 84th Division, still training. In August 1918, that division moved to France, and Colonel Krueger came along with it. Once in France, however, he received orders to assume the duties of chief of staff of the newly developed Tank Corps. Before he could fully settle into his new post, the armistice ended his hopes of commanding troops in combat.

The interwar years were disappointing for Krueger as they were for all Army officers. There was little interest in preparedness, and budget constraints kept the Army small and promotions slow. After commanding the 55th Infantry Regiment in Kansas, Krueger attended and then taught at the nation’s prestigious service schools, the Army War College, the Navy War College, and the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia. He then served in the War Plans Division of the War Department, achieving the rank of brigadier general.

Krueger formulated his own command philosophy. He would write that a great commander “no matter how recklessly he challenges fate again and again he by no means rushes headlong and aimlessly into the unknown, but knows perfectly where he must call a halt, turns in his turn and at the same time endeavors to supplement his victory through policy.” He went on to state that a good leader has the “ability to form a clear resolution without hesitation, and to put it into execution.” This philosophy would become the hallmark of his campaigns during World War II.

By 1938, General Krueger was chief of the Army War Plans Division, and in September of that year he took command of the 16th Infantry Brigade at Fort George Meade in Maryland. Within a few months, he was promoted to major general and assumed command of the 2nd Infantry Division in Texas. There he became involved in reorganizing the Army and testing these new organizations. By this time, he had established his final command methods. These included educational preparation, cool and flexible thinking, a decentralized command structure, caring for the soldiers under his command, and placing value on aggressive and bold offensive actions.

In June, General Krueger was given command of the VIII Corps in larger Army maneuvers and with recently called up National Guard divisions under command. He took care to integrate his Regular Army troops and the National Guardsmen, allowing for the Guard’s insufficient training and shortage of personnel.

General Krueger retained command of VIII Corps to the end of 1940. Unknown to him, he was being considered as a replacement for the commanding officer of the Hawaiian Department, but the job went to Maj. Gen. Walter C. Short instead. Marshall now had other plans for Krueger and advised him in a confidential letter in April that he would be assuming command of the Third Army upon the retirement of its current commander. Marshall appointed Kreuger commander of the Third Army on May 15, 1940.

General Krueger immediately set about organizing his staff and preparing for more maneuvers. He requested as his chief of staff Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower, then serving as IX Corps chief of staff. Upon arrival, Eisenhower was instructed to recruit and organize a Third Army staff group. The Third Army busied itself with training and maneuvers for the balance of the year, testing subordinate corps and divisions. Indeed, for the next two years Krueger and his Third Army trained numerous corps and divisions that passed through their command.

When the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor General Krueger was approaching his 61st birthday. He was despairing of getting a field command or commanding combat troops overseas. Like most senior officers, he knew that General Marshall had a policy of assigning younger officers to combat commands. But all that was about to change. In the Philippines General MacArthur’s forces had been overrun and surrendered while MacArthur and his family were ordered to Australia. Soon he was leading an American-Australian effort to recapture New Guinea and return to the Philippines. But as that effort grew larger, MacArthur wanted an Army headquarters to manage and tactically direct his growing ground forces. He radioed to Marshall in Washington, “I recommend that the Third Army under General Krueger be transferred to Australia. I am especially anxious to have Krueger because of my long and intimate association with him.”

Although General Marshall had authorized his transfer, he would not release the Third Army headquarters. Instead, Krueger was to organize the new Sixth Army headquarters and take it to New Guinea. He was, however, allowed to take with him some of his key staff officers from Third Army.

Arriving in Australia on February 7, 1943, General Krueger learned that his new command would be in disguise. To do this he created Alamo Force, essentially Sixth Army in disguise and reporting directly to MacArthur’s headquarters. Krueger soon learned the way of war in the SWPA. MacArthur “formulated all strategic plans, issued directives designating the operations to be undertaken, the commanders to conduct them, the forces and means to be used, the objectives and the missions to be accomplished. But in conformity with the principle of unity of command, he did not prescribe the tactical measures or methods to be employed.”

Krueger faced some serious difficulties. His forces were spread over 2,000 miles from Australia to New Guinea. His only two combat divisions, the 32nd and 41st Infantry Divisions, were seriously depleted and ravaged with disease from earlier battles. Supplies were inadequate, and Australia’s port and rail facilities were poorly prepared for the volume the coming campaign would demand of them.

General Krueger first put a high priority on logistical support for the frontline units. He was appalled to learn that the soldiers of the 41st Infantry Division had to sew patches on their ragged uniforms because replacement clothing was unavailable. Deficiencies were to be corrected immediately, requisitions filled promptly. Next Kreuger addressed the sickness issue. He sent to the United States for experts on tropical diseases and set up a malaria treatment center at Rockhampton. Malaria control units were established, and the responsibility for controlling the disease fell to local commanders.

Meanwhile, MacArthur was also busy. Soon he presented Krueger with 13 planned amphibious assaults along the north coast of New Guinea. These operations were all designed to bring forward Allied air support which in turn would support the next operation.

First on Krueger’s list were the islands of Kiriwina and Woodlark. By May 28, Alamo Force had submitted a plan of operations to the SWPA that was immediately approved. The operation went off as planned, and there was no enemy opposition. This operation verified the training and planning of Sixth (Alamo Force) Army and provided experience for the assault troops.

Next were landings on New Britain at Arawe and Cape Gloucester. Prior to these, General Krueger grew increasingly concerned about the lack of good ground intelligence he received from SWPA. He called upon Maj. Gen. Innis P. Swift, commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, to establish a training camp for reconnaissance teams. The Alamo Training Center was established on Ferguson Island, off the southeast tip of New Guinea, and was soon producing a small but highly effective reconnaissance force called the Alamo Scouts.

General Krueger then launched his Army-Marine Corps units against New Britain. This ended operations for 1943. But early in February 1944, Krueger sent General Swift’s men to seize the Admiralty Islands, which completed the encirclement of the major enemy base at Rabaul. Then Sixth (Alamo Force) Army concentrated on the advance up the north coast of New Guinea with a final goal of the Philippines. One after another Japanese enclaves fell to the attacking American forces—Hollandia and Aitape in April, Wakde Island in May, Biak Island also in May, Noemfoor Island in July, and Sansapor on the western tip of New Guinea at the end of that month. At the end of the summer of 1944, the Japanese posts in New Guinea had all been overrun or left to be mopped up by Australian forces. General MacArthur had completed his approach to the Philippines. The need for the deceptive Alamo Force designation was also removed. Henceforth, General Krueger’s command would be known by its official designation, Sixth Army.

By July SWPA was making early plans for the seizure of the Philippines. The planning continued for months, and due to new intelligence some operations were cancelled and others moved forward. Sixth Army’s invasion of Leyte, a central Philippine island, was moved forward from December to October 1944. General MacArthur was about to keep his pledge to return to the Philippines, and he would be taken there by General Krueger’s Sixth Army.

Supported for the first time by a huge naval armada, including both the Third and Seventh Fleets, the Sixth Army landed on Leyte on October 20, 1944. General Krueger’s 202,000 soldiers initially faced weak opposition, but their landing drew the attention of the Japanese high command, which ordered a full-scale defense of Leyte. Reinforcements were rushed to the island, and the campaign lasted for more than three months.

Beset by increasing enemy strength, failure to build the required airfields, and the increasing Japanese air opposition, including the new kamikaze threat, General Krueger developed plans to speed his advance. When slowed by a strong Japanese defense along a mountain range, he asked for and received additional troops that he used to conduct an amphibious landing behind Japanese lines, breaking the stalemate and ensuring the end of organized Japanese resistance.

Even before General Eichelberger’s new Eighth Army took over clearing Leyte, General Krueger was busy planning for MacArthur’s next step, the main Philippine island of Luzon. Krueger’s staff found fault with the estimates of SWPA headquarters, which claimed that there were only about 158,000 enemy troops on the island. Colonel Horton V. White, Krueger’s intelligence officer, disagreed, claiming that there were at least 234,500 enemy troops on Luzon.

The Luzon campaign began on January 9, 1945, when Sixth Army landed 203,608 troops at Lingayan Gulf. From the moment the troops established the beachhead, MacArthur urged a rapid advance on the capital city of Manila. Krueger, who knew from various intelligence sources that a massive enemy force lay in the mountains to his left flank, refused to rush headlong into Manila while leaving his flank exposed. There were repeated arguments between the two, and MacArthur resorted to various stratagems to urge Krueger to speed his advance, including threatening his removal from command and, in one instance, moving his own headquarters closer to the front than Sixth Army’s in an attempt to embarrass Krueger. Fortunately, none of this dissuaded Krueger from his planned pace of advance. Postwar records indicate that in fact the Sixth Army was outnumbered on Luzon, with more than 267,000 enemy troops on the island opposed by Krueger’s 203,000. Further, most of these enemy troops were waiting in those mountains on the left flank of Sixth Army as MacArthur urged it to speed toward Manila, further exposing that vulnerable flank.

Once Manila, a city left in ruins by the battle necessary to secure it, was liberated, MacArthur seemed to have lost much of his interest in the remainder of the campaign. In fact, Sixth Army would be fighting on Luzon until late July, when General Eichleberger’s Eighth Army relieved it. By that time Krueger and his Sixth Army staff were deep into planning for the invasion of the Japanese home islands. This plan, known as Operation Downfall, would occupy them until the Japanese surrender. But even as the planning continued and the troops gathered the Japanese surrendered.

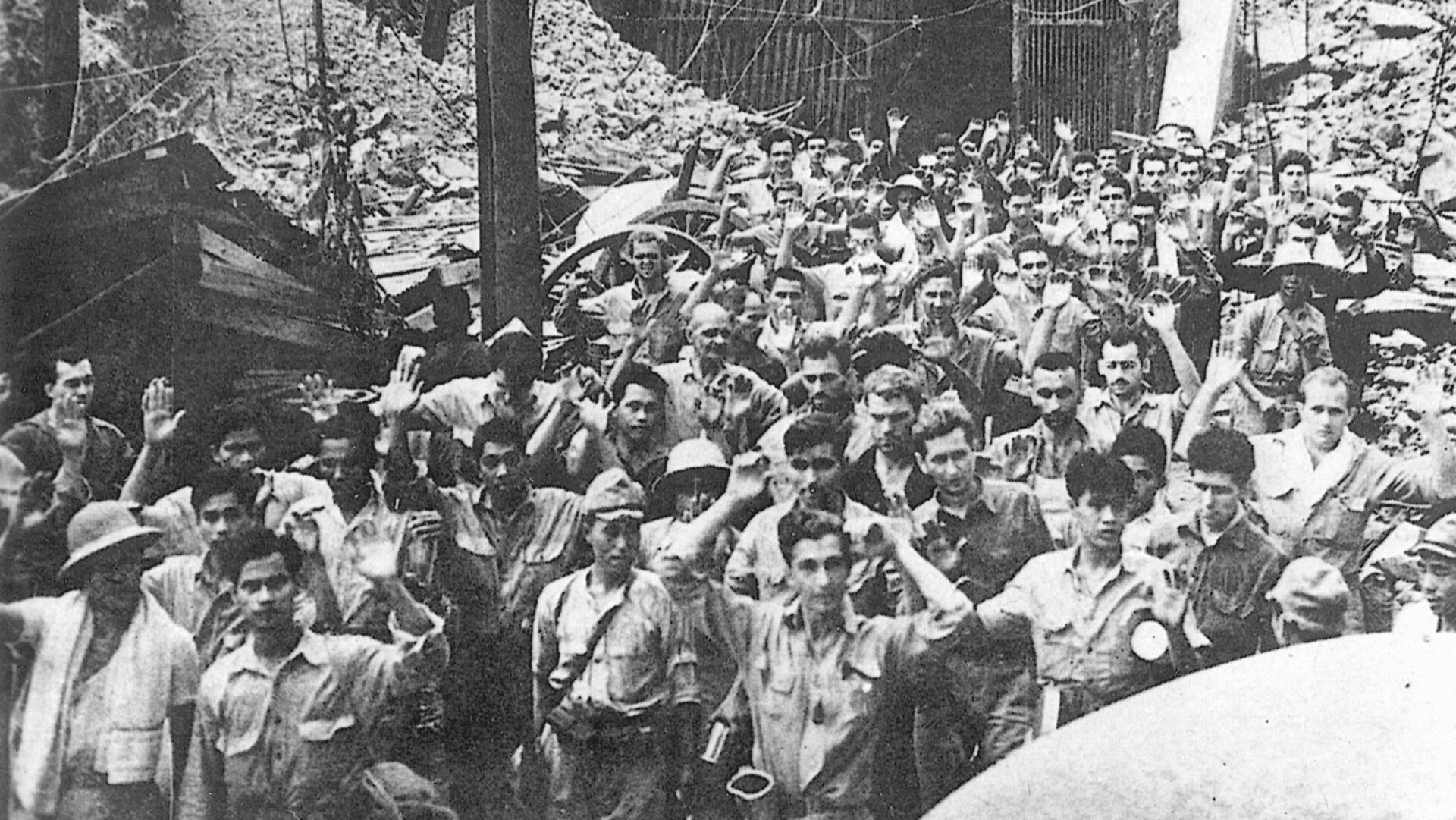

Instead, General Krueger and his headquarters were to occupy the islands of Kyushu, Shikoku, and western Honshu, an area with a population of more than 40 million civilians. With three corps headquarters and ground troops under command, Krueger supervised the demobilization of the Japanese military forces in his area, instituted military government, rescued Allied prisoners of war, and verified that the Japanese carried out all the terms of the surrender. The Sixth Army landed in Japan on September 23, 1945, and was fully engaged in these duties by early November.

On December 31, 1945, the Sixth Army was relieved by the Eighth Army, and General Krueger was ordered to deactivate his command. General Krueger was able to begin his journey home. He and Grace had decided to make Texas their permanent home, and after retirement they settled in San Antonio.

Grace Krueger died of cancer in 1955. At her funeral a former staff member and friend recorded, “Walter Krueger has broken terribly, crying openly much of the time. Said he would join Grace soon. He is … shaken with what he had to undergo.” Despite depression, Krueger continued to write letters to friends and even attended a memorial service in the Philippines in 1960 and General MacArthur’s birthday in New York in 1963. But his poor health eventually brought on pneumonia, and General Walter Krueger died on August 20, 1967, unrecognized and largely forgotten by the country he served so long and so well.

Nathan N. Prefer is the author of several books and articles on World War II. His latest book is titled Leyte 1944, The Soldier’s Battle. He received his Ph.D. in Military History from the City University of New York and is a former Marine Corps Reservist. Dr. Prefer is now retired and resides in Fort Myers, Florida.