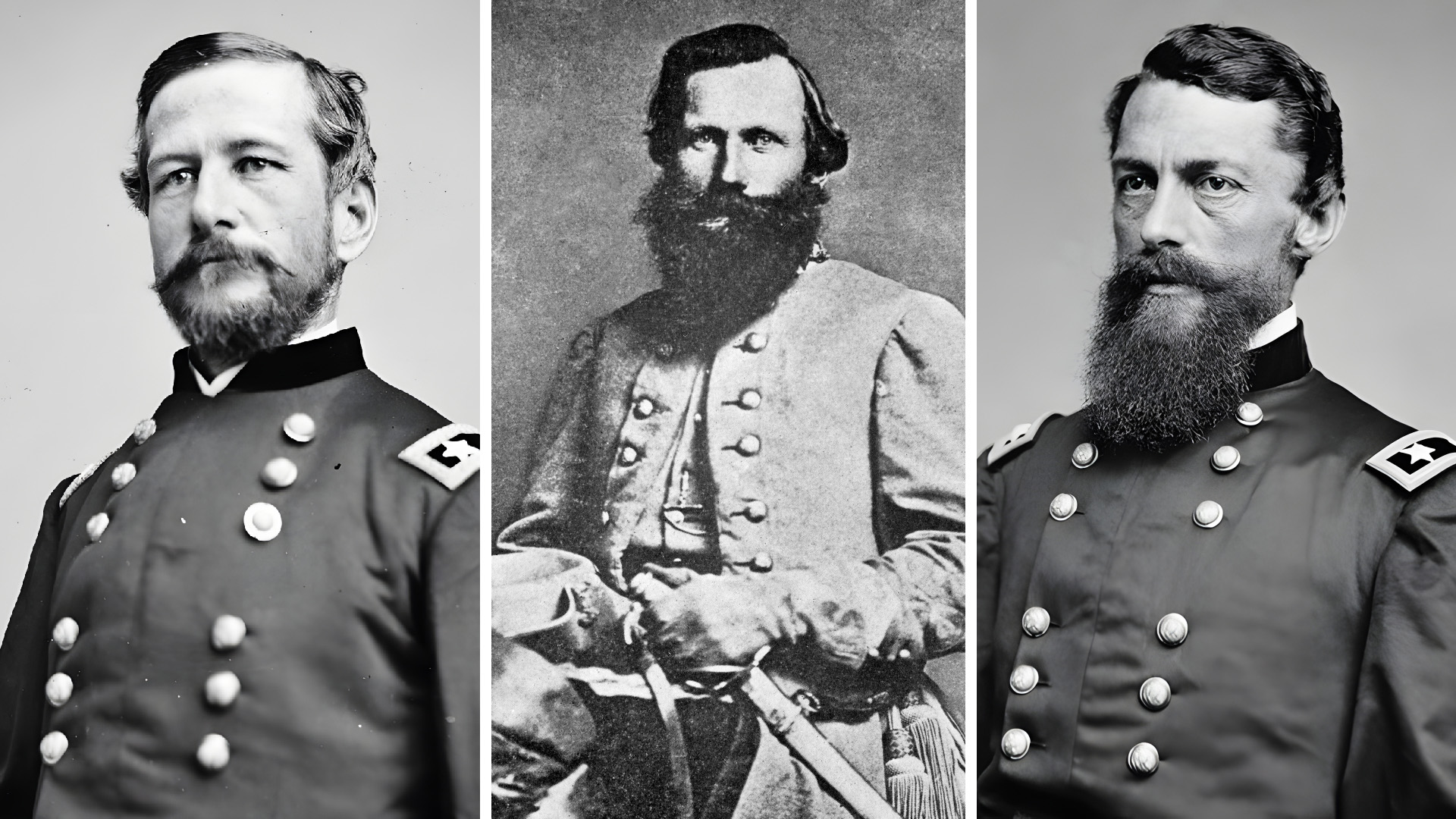

Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton’s outward appearance was that of a well-groomed man. He kept his beard and moustache neatly trimmed, parted his wavy hair on the side, and wore a wide-brimmed hat like a dandy. Unlike many American Civil War generals whose fiery gaze in period portraits makes it seem that whatever object they looked at might suddenly burst into flames, the native Washingtonian has a look of contentment, as if he had just finished a good repast.

Major General Joe Hooker, commander of the Army of Potomac, selected Pleasonton on June 7, 1863, to succeed Brig. Gen. George Stoneman as commander of the three-division corps, which “Fighting Joe” had created. Hooker had sacked Stoneman in the wake of the Chancellorsville campaign the previous month for the poor results he had produced leading the newly established corps on a raid behind Confederate lines.

Stoneman’s raid on Lee’s communications network and supply lines had failed from several standpoints. First, Stoneman had allowed heavy rains to delay his start. Second, he failed to push the units under him to reach key targets, such as spans on the Virginia Central Railroad, or destroy the primary supply hub of the Army of Northern Virginia at Guiney’s Station on the Richmond, Fredricksburg, and Potomac Railroad. Third, the damage the raiders did manage to inflict was so slight that Confederate engineers were able to repair it in just a few days.

Pleasonton’s seniority and experience were the likely reasons Hooker picked him to succeed Stoneman. A graduate of West Point’s Class of 1844—a group that included Generals Winfield Hancock, Simon Buckner, and Alexander Hays—Pleasonton had a good military pedigree. Pleasonton graduated higher than all three of those classmates; he ranked seventh in a class of 25. He served with distinction in the Mexican War and afterward in various posts on the frontier. By June 1863, he had commanded a cavalry division through three campaigns: Maryland, Fredricksburg, and Chancellorsville.

Unfortunately, the Chancellorsville campaign brought out his talent for self-aggrandizement. Like many other self-promoting generals in that war, including his predecessor, Pleasonton liked to inflate his performance on the battlefield. At Chancellorsville, Pleasonton had remained with the main body of Hooker’s army to coordinate the use of the second brigade of his division. When Jackson’s corps swept over the Union XI corps like a wall of flood water, Pleasonton was at Hazel Grove with Lieutenant Joseph Martin’s horse artillery and several batteries belonging to Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles’s III Corps. In his after-action report, Pleasonton took credit for commanding all of the artillery—about two dozen guns—at the clearing and in repulsing Jackson’s entire corps. In reality, the Confederate numbers were dramatically smaller and Pleasonton only directed Martin’s battery.

Nonetheless, Pleasonton showed at Hazel Grove that he had the stomach to fight—even if his reports were highly suspect. Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry had declined to engage Stoneman during his raid. But when Pleasonton launched what amounted to a frontal attack on the rebel cavalry at Brandy Station, Stuart had no choice but to give battle. That encounter, not Stoneman’s uncontested raid, was the true test of Hooker’s shiny new cavalry corps.

—William E. Welsh

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments