By David Norris

On the last day of May 1862, heavy gunfire rumbled and thundered in the distance beyond the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Gloomy clouds overhead reinforced the darkness that shadowed the Union Army. Only the day before, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac had seemed poised to move decisively against Richmond, but a torrential rainstorm that night had turned the roads into deep quagmires. McClellan, as usual, decided to wait.

McClellan had greatly restored the army’s morale in the months after the Union disaster at Bull Run on July 21, 1861. He was sensitive to the needs of his soldiers, and the men in the ranks were devoted to him. A methodical planner, McClellan initially enjoyed great success after opening the Peninsula campaign in March 1862. Outmaneuvering the Confederates, he continually pushed General Joseph Johnston’s forces inland into Virginia from the Chesapeake. By May, weeks of successful campaigning had brought the enemy nearly to the gates of Richmond. So close to the Rebel capital were the lead elements of McClellan’s army that they could hear the clanging of church bells in Richmond.

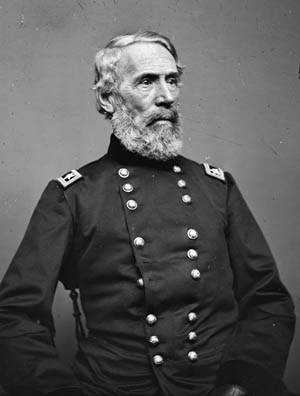

McClellan’s opponent, Joseph Eggleston Johnston, mirrored him in many ways. Born in Virginia in 1807, Johnston had graduated with Robert E. Lee in the West Point class of 1829. (McClellan had graduated from the Academy in 1846.) Johnston’s steady and exemplary service in Indian conflicts and the Mexican War earned him several brevets. In 1860 he was appointed the U.S. Army’s quartermaster general. Joining the Confederate Army in 1861, he distinguished himself at the First Battle of Manassas, which Southerners called Bull Run. Promoted to full general in August 1861, Johnston was assigned command of the Army of Northern Virginia early in 1862.

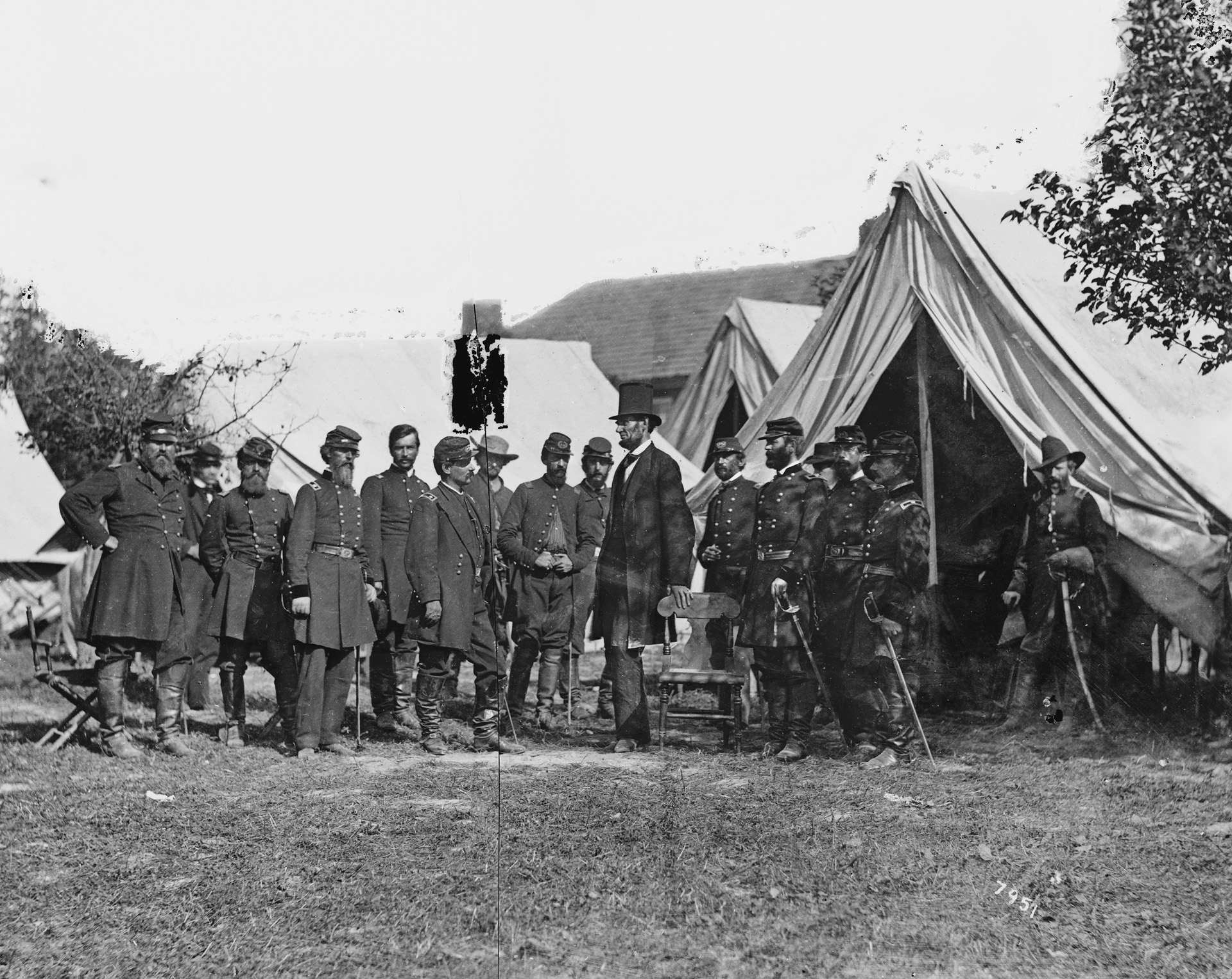

Both Johnston and McClellan were thoughtful, cautious commanders. McClellan, in particular, constantly pleaded for reinforcements. President Abraham Lincoln, wanting more aggressive action, grumbled that the general had a bad case of “the slows.” McClellan believed he was facing a Confederate army much larger than his own; in reality, he outnumbered the enemy by 40,000 men. For his part, Johnston knew he was outnumbered and sought to keep his army out of harm’s way while he waited for a chance to strike a decisive blow against the enemy.

Crossing the Chickahominy

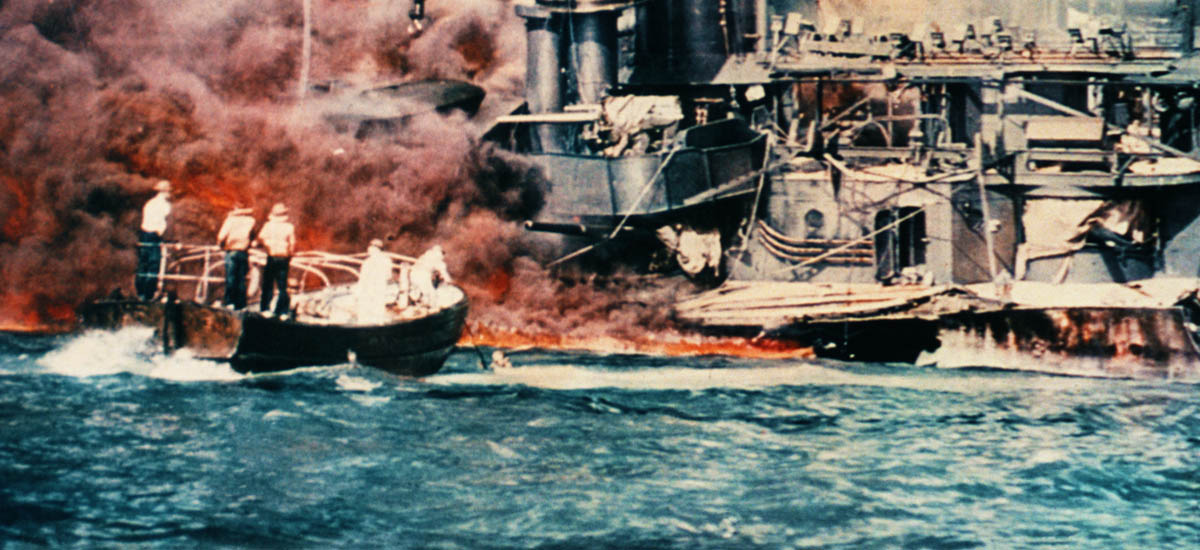

As the Union Army edged ever closer to Richmond, the James River offered a tempting avenue for the Navy to aid the campaign with heavy artillery and ironclad vessels. On May 15 a Union flotilla was battered by stubborn Confederate guns atop the high ground along the river at Drewry’s Bluff. The armor of the ironclads Monitor and Galena could not withstand the advantageously placed land batteries and had to turn back. It was plain that the James would not lead Northern forces into Richmond.

The Union Navy’s failure did not assuage worries in Richmond about the advancing enemy, and Johnston’s next move only increased the alarm. Although Confederate batteries blocked the James, Johnston worried that Union forces might still approach the capital from the river below Drewry’s Bluff. Accordingly, he withdrew all his troops south of the Chickahominy. The troops settled into positions three miles east of Richmond, behind a line of earthworks dug the year before.

Even more alarming to Confederate prospects were reports about Union Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s I Corps. Numbering more than 30,000 men, McDowell’s corps had kept well north of Richmond to guard Washington. Now it was reported to be marching toward Fredericksburg on its way south to join McClellan. Uniting I Corps with McClellan’s men would create an overwhelming army of 135,000 troops—the largest military force yet seen in North America. Although the potential junction with McDowell would create a vast and unstoppable Union force, it also gave Johnston an opening. To speed the union with McDowell while maintaining pressure on Richmond, McClellan had dangerously split his vast army in two. Keeping most of his men north to be nearer to McDowell, McClellan shifted two corps south of the Chickahominy. If Johnston swiftly struck and crushed the detachment below the river, the remaining Union forces would be vulnerable to a quick attack.

The Chickahominy was an insignificant squiggly line on a map, only 15 yards wide in dry weather. Before the war, several bridges provided easy crossing points, but the shallow river was easily fordable in many places. Occasionally splitting into multiple streams to flow around swampy islands, the river twisted through a belt of wooded wetlands 300 to 400 yards wide. Beyond the swamps the terrain rose slightly into stretches of woods or cleared and cultivated bottom land cut with drainage ditches. Despite its shallowness, the Chickahominy was a formidable barrier. The month of May was notorious for relentless and heavy rain, and the river overflowed its banks and kept on rising over wide stretches of swamps and bottom lands. Farther back from the stream the ground was so saturated with water that it had become a mushy quagmire in which artillery, wagons, and horses were virtually useless.

Johnston ordered all the Chickahominy bridges destroyed after he withdrew south of the river on May 16. Union troops set to work building new bridges. They quickly erected Bottom’s Bridge, a span crossing the stream at the Williamsburg Road on the direct route to Richmond. A short distance upstream, they also repaired the Richmond & York River Railroad bridge. Union forces began crossing the river on May 20. Eventually, two Union corps, commanded by Maj. Gens. Erasmus D. Keyes and Samuel P. Heintzelman, assumed positions on the south bank of the river. McClellan’s other three corps, under Maj. Gens. Edwin Sumner, William Franklin, and Fitz John Porter, remained on the north bank.

A Plan to Attack the Divided Union Army

Keyes moved his corps along the Williamsburg Road. The night of May 26 brought more rain to soak the troops despite their rubber blankets. Pickets posted in thick brush found the night so dark that “had a battle line of the enemy been within bayonet’s thrust, it would have been invisible.” Occasionally skirmishing with the Confederates, Brig. Gen. Silas Casey’s troops settled into a crossroads community called Seven Pines, which was distinguished by two curious-looking twin farmhouses. Originally, the houses were intended to be the opposite ends of a much larger mansion. The owners planned to live in the houses while construction went on for the palatial main building, but the intervening rooms were never built. Near the houses was a tremendous woodpile, 10 to 12 feet high and more than 100 feet long.

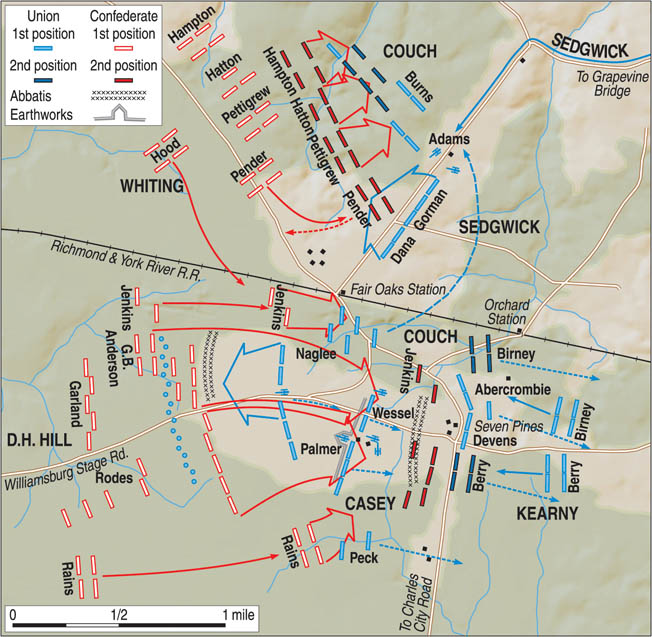

Three-fourths of a mile west of Seven Pines, Casey’s soldiers cut down trees to build a line of abatis in front of their earthwork. Half a mile to the east of the front line of works, a longer and heavier line of abatis shielded the Williamsburg Road and Seven Pines. Between the two lines was the Union camp, situated behind a line of defenses anchored by a five-sided earthwork fort called Casey’s Redoubt. Behind Casey’s men was Brig. Gen. Darius Couch’s division; in their rear was Heintzelman’s corps. Farther back along the Williamsburg Road toward Bottom’s Bridge were the divisions of Brig. Gens. Philip Kearny and Joseph Hooker. To their left the Federals were shielded by White Oak Swamp, but to the front and right the Union works were unprotected by any natural barriers. Keyes recognized the peril and told staff officers on May 29 that “our position is certain to tempt the enemy to attack us.”

Seeking to guarantee quick access to reinforcements from across the Chickahominy, Keyes put his soldiers to work building several new bridges. Bridging the river was only part of the effort needed for the crossings. Each bridge required hundreds of yards of corduroy roads to provide access across the saturated bottom lands. One of the new bridges was built by the 1st Minnesota Regiment. Company officers supervised the work, with no help from Army engineers. Without regulation bridge materials, soldiers chopped down trees in the surrounding woods to hew beams and planks. To support the bridge, they built timber cribs. Each crib sank deep into the mud, surrounded with stones to weigh them down. Once the pilings were firmly set, log stringers were laid across them to hold the roadway, which was then floored with split logs. Holding the bridge together were withes, flexible branches that firmly lashed planks and beams together. Wild grapevines used for the withes provided the name for the span: Grapevine Bridge.

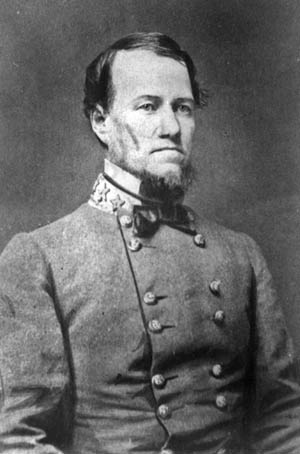

By May 25 Johnston had set his plans in motion to attack the divided Union army, calling in troops from Petersburg, Gordonsville, and Fredericksburg. When assembled, the Confederates would number nearly 75,000. Each of Johnston’s three top commanders had graduated from West Point in the Class of 1842. Maj. Gen. James Longstreet of South Carolina had served in the Indian wars and the Mexican War. Also from South Carolina, Maj. Gen. Daniel Harvey Hill had left the Army after the Mexican War to become a college professor and administrator in North Carolina. As colonel of the 1st North Carolina Regiment he won an early Confederate victory at the Battle of Big Bethel on June 8, 1861. Kentucky-born Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith had also left the Army in the 1850s. His training as a military engineer had helped secure him the post of street commissioner of New York City.

Johnston originally planned to move against the Union forces on both sides of the Chickahominy on May 29 and shatter McClellan’s army before it became even larger with the addition of McDowell’s men. But late on the evening of May 28, Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart sent word that McDowell had been diverted to deal with Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s army in the Shenandoah Valley. For the time being, at least, Johnston could focus on smashing the smaller wing of the Union army. If the attack succeeded, the odds would be less daunting for an attack on the rest of the Federals north of the stream. The Confederate move was set for Sunday, May 31.

Johnston divided his army in two for the attack. Two of Smith’s divisions, under Maj. Gens. A.P. Hill and “Prince John” Magruder, would shield the Confederates from enemy troops on the other side of the Chickahominy. For the main attack against the 31,500 troops of Keyes and Heintzelman, Johnston allotted Longstreet 40,000 troops. They would advance along three different roads and strike from three directions at once. D.H. Hill had orders to take the Williamsburg Road, which ran directly east from Richmond to Seven Pines, and move against the enemy center and right. Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger would cross the Williamsburg Road and take the Charles City Road, which ran to the southeast. From there, a rural road ran north to a position menacing the Federals’ left flank.

Longstreet, in turn, would take the Nine Mile Road. For several miles, the Nine Mile Road ran parallel and to the north of the Williamsburg Road. But, it took a southeastern turn to cut across the Richmond & York River Railroad at Fair Oaks before meeting the Williamsburg Road at Seven Pines. Coming down from the northwest against Seven Pines, Longstreet would hit the Union right, prevent the escape of the enemy to Fair Oaks, or block any Union reinforcements coming from the upper Chickahominy. For reinforcements, Brig. Gen. W.H.C. Whiting’s division was to follow Longstreet’s force.

The timing of the attack depended on Huger. Once his troops were in place on the Confederate right, he was to send a message to Hill, who would then open the attack on the enemy center. The sound of Hill’s firing would be the signal for Longstreet to move in against the Union right. Huger could then move against the left. Johnston’s plan promised great results, but he evidently did not clearly explain it to any of his commanders. To Longstreet, who was placed in charge of the attack, Johnston gave only verbal orders. The two generals spoke at length on May 30, but by the next day it was clear that Longstreet had misunderstood his orders. Huger was not told that he was the key to the Confederate offensive. There was only a vague order advising him to “be ready, if an action should begin on your left, to fall upon the enemy’s left flank.” It would prove to be a costly oversight.

Longstreet’s Deviation From the Plan

Heavy rain pounded both armies on the night before the attack, and the Chickahominy quickly surged to new heights. At about 11 pm on May 30 a detail of pickets from the 33rd New York went to guard one of the half-built Chickahominy bridges. Within a short time they were cut off from their main camp by the swiftly rising water. When another shift came to relieve them at 2 am, they found the pickets “standing nearly up to their arm-pits in the now new channel, and others, having lost their footing, were clinging to trees, for dear life.” The relief detail sent for boats to rescue their comrades.

On the morning of May 31 Longstreet’s men rose from their camps. Bivouacked at the Fairfield Race Course on the northeastern edge of Richmond or scattered farther east along the Nine Mile Road, they were within easy reach of the jumping-off position Johnston intended. But for some reason Longstreet didn’t follow Johnston’s plan. Instead of taking the Nine Mile Road toward Seven Pines, Longstreet ordered his division to march west, then turn south toward the Williamsburg Road.

Longstreet told no one of his decision to take the Williamsburg Road, and his seemingly casual decision scrambled Johnston’s carefully laid plans. Whiting, trying his best to follow orders, found the Nine Mile Road clogged by Longstreet’s men but could not locate any of the senior officers. When Whiting wrote to warn Johnston that the road was blocked, the commander sent back a note saying merely that Longstreet would precede him. Going to Johnston’s headquarters in person, Whiting found that no one knew what was happening. Everyone assumed that Longstreet was well down the Nine Mile Road, and Johnston was surprised when a staff officer was unable to find him anywhere on the road.

In fact, a stream called Gillis’s Creek, overflowing from the previous night’s rains, had blocked Longstreet’s march to the Williamsburg Road. To avoid a long detour, his men drove a wagon into the creek and used it to support a makeshift bridge. Huger arrived on his way to the Charles City Road to open the battle and was forced to halt while thousands of Longstreet’s men trod single-file across the little bridge ahead of him. Ultimately, Huger was stuck near Richmond until 10:30 am, long after he was supposed to be facing the Union left flank. Because of Johnston’s vague and partial orders, it wasn’t clear to the other officers that by delaying Huger they were delaying the start of the entire operation.

Johnston dispatched another staff officer, Lieutenant J.B. Washington, to check the Nine Mile and Williamsburg Roads and locate Longstreet. Washington never came back; he was taken by Union pickets. He told them nothing, but the mere presence of a member of the commanding general’s personal staff was a tipoff that something large was being planned by the Confederates. A message from another staffer, Captain R.F. Beckham, reached Johnston’s headquarters at 10 am. Beckham reported that instead of taking the Nine Mile Road, Longstreet now was on the Williamsburg Road where the Charles City Road branched off to the south. The attack was going to have to wait until D.H. Hill and Huger could squeeze past the congested road to their assigned positions. Johnston had expected the battle to begin early in the morning. He fretted and worried as invaluable hours crawled by with no news.

Several hours late, D.H. Hill finally reached his assigned place on the Williamsburg Road. Halting a half mile ahead of Casey’s pickets he waited anxiously for Huger, not knowing that the other general was still waiting far behind them. Brig. Gens. Robert Rodes’s and Gabriel Rains’s brigades were on Hill’s right, south of the road; the Confederate left was held by the brigades of Brig. Gens. Samuel Garland and George B. Anderson. The woods and brush were so thick that many of the officers could see no farther than the neighboring companies. To minimize friendly-fire casualties, each man was ordered to tie a strip of white cloth around his hat.

At last, at 1 pm, Hill learned that Huger’s advance brigade was in position. Hill ordered the signal guns fired to launch the attack. Rodes, supported by Rains, marched forward first. The left brigades moved out 15 minutes later. The advancing Confederates held their lines tolerably straight despite slogging through water that was three feet deep in places.

“Shoot That Man on Horseback!”

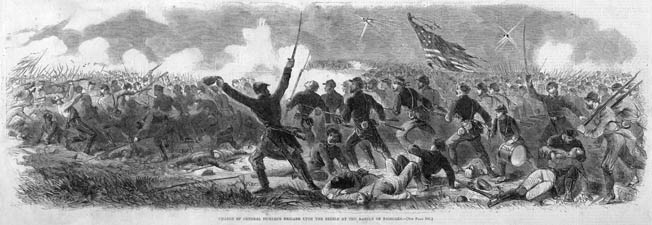

In the Union camp the first sign of the approaching Confederates was a pair of artillery shells whistling overhead to interrupt the noontime meal. Hill sent Rains to make a flanking movement against the Union left. Meanwhile, Rodes pressed forward toward the enemy works, smashing through Casey’s pickets and his outermost regiment, the 103rd Pennsylvania. The Confederates surged forward until they stopped against the main line of Union muskets and six guns inside Casey’s Redoubt.

Rains arrived on the scene to confront the left face of the redoubt. Hill personally led Captain Thomas H. Carter’s battery, the King William Artillery, and found the Virginians a good field of fire against the enemy earthwork. South of the fort the tall trees edging White Oak Swamp offered ideal firing positions for Confederate sharpshooters. Most of the gunners and two-fifths of Casey’s troops were hit. With Rodes and Rains pressing in from two directions, Casey’s troops crumbled. Streaming out of the redoubt in panic, they swept around Casey, who stood in their path imploring them to halt. Eight guns were abandoned to the Rebels. The attackers cut through the abandoned Union camps and charged over a clearing in front of the second Union line of works 150 yards behind Casey’s Redoubt. The line of abatis at Seven Pines was more strongly held than Keyes’ original line, and Casey’s scattered troops joined Couch’s division, which was already in place.

On the Confederate right Rains’s regiments slowed down on the edge of White Oak Swamp, leaving Rodes’s men to take most of the heavy defensive fire. Wounded in the arm, Rodes stayed in the saddle and continued to lead his troops. They were under heavy fire in the clearing in front of the abatis when more Union troops from Kearny’s division appeared in the woods to their right. Rodes had to shift some of his men to the right to meet the new threat.

Ahead of Rodes’s division Colonel John B. Gordon and the 6th Alabama pushed deep against the Union line. Gordon’s lieutenant colonel, adjutant, and major were killed. Half the company officers and many of the rank and file also fell dead or wounded. Gordon was conspicuous on his horse, and some of his men heard the enemy shouting, “Shoot that man on horseback!” Bullets tore through the colonel’s uniform and struck his canteen but never touched him. Among the wounded Gordon glimpsed his 19-year-old brother, Captain Augustus Gordon, lying amid a scattering of dead men. The younger Gordon was shot through the lungs. Ascertaining that his brother was still alive, if bleeding heavily, Gordon pressed on. Only after the battle did he learn that his brother would recover. His force was trapped under heavy fire on ground so saturated with rain that many men were up to their hips in water. First aid details rushed about the field, propping wounded men against trees and stumps so that they would not drown before they could be taken away for medical aid.

D.H. Hill appealed for help, and Longstreet sent forward Colonel James S. Kemper’s brigade to relieve Gordon. Kemper’s men met streams of wounded comrades flowing back from the fighting. They pushed through Casey’s abandoned camp but came under heavy fire from the abatis to their front. Adding to the fearsome roar of the guns and screams of the wounded was the sound of bullets ripping through the canvas of the tents. A Union soldier visiting the scene after the battle counted more than 200 bullet holes in a single Sibley tent in camp. Kemper’s men pulled back to take cover in the captured Union earthworks on the other side of the camp, pinned down under heavy fire.

Eventually, orders came for the Alabamians to pull back. They gave ground slowly, bringing back as many of the wounded as they could. When Gordon rejoined his division he learned that Rodes’s wounds had forced the general to relinquish command to him. Gordon’s regiment that day lost 91 men killed, 277 wounded, and five missing. The 373 casualties included 59 percent of the 6th Alabama, a grim record at the time for the highest loss by a single Confederate regiment.

The Acoustic Shadow at Seven Pines

Across the Williamsburg Road the brigades of Garland and Anderson hit the Union center. After leaving the Williamsburg Road and advancing to the northeast, Anderson detached Colonel Micah Jenkins and two regiments. Jenkins pushed through the Union lines near the left end of the abatis, cutting off Couch and part of his force, which retreated toward Fair Oaks. Kearny had to shift around from the Union left to deal with Jenkins.

Although Johnston was only two miles from the developing battle, a peculiar atmospheric condition known as acoustic shadow muffled the sound of cannon and musket fire. Adding to the confusion, his staff had failed to keep Johnston informed of conditions on the battle front. In fairness, the belts of thick woods and deep pools of mud and water kept the aides from gathering and relaying intelligence in a timely manner. Johnston knew only that Longstreet had taken the wrong road several hours ago and that his whole plan had fallen apart. “I wish all the troops were back in camp,” Johnston grumbled.

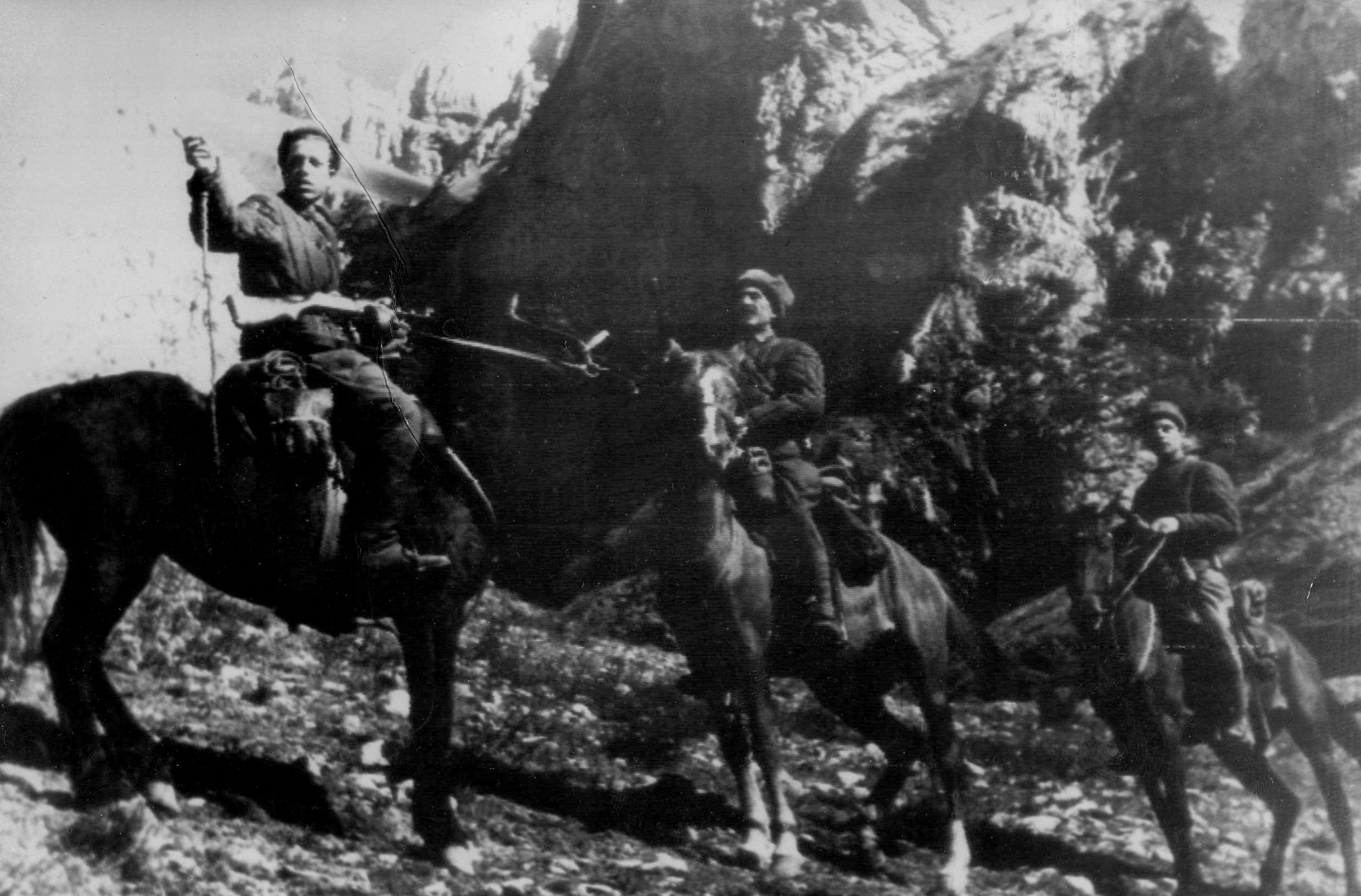

Johnston’s old classmate Robert E. Lee joined him at his headquarters. During the afternoon they heard a dim echo that sounded like cannon fire. Lee thought he heard a hint of musketry as well, but Johnston concluded that it was merely an exchange of cannon fire. About 4 pm the wind shifted enough to allow the cacophonous sounds of battle to reach Johnston. At the same time, a courier arrived with a request from Longstreet for reinforcements. It was the first clear report the Confederate commander had received that day. Johnston left his headquarters and personally led Whiting’s division down the Nine Mile Road toward the fighting. Just as Johnston left, Confederate President Jefferson Davis arrived on horseback to monitor the progress of the battle. More than one officer believed that Johnston had seen Davis approaching and had left hurriedly to avoid talking to him.

Johnston reached Fair Oaks at 5 pm. He planned to send Whiting to drive the enemy out of Seven Pines and secure a major victory. Suddenly, several Union cannons boomed on their left—it was Couch’s artillery. Cut off from Seven Pines, Couch was leading his force back toward the Chickahominy when he saw Whiting’s troops in the distance, formed a line of battle, and ordered his guns to open fire. Whiting’s troops were repulsed twice by Couch’s guns. They surged forward again as the Union gunners ran out of canister. The artillerymen kept firing with explosive shells, the fuses cut down so short that they burst almost instantly after leaving the muzzles.

Johnston’s Injuries

Although Johnston’s headquarters was in an air pocket that muffled the sounds of battle, McClellan back at Gaines’ Mill could clearly hear the increasing volume of fire. He alerted Brig. Gen. Edwin Sumner and his II Corps to be ready to march. Sumner wasted no time; when a final order arrived at 2:30 to cross the river, Sumner already had his corps at the edge of the flooded stream. The surest crossings, Bottom’s Bridge and the Richmond & York River Railroad bridge, were too far in the Union rear to allow the corps to cross in time. Sumner had his choice of two recently built makeshift spans. One brigade made it across one of the bridges, but the planks were so deep underwater that the soldiers were practically wading across. The bridge collapsed soon afterward.

The loss of the first bridge left only Grapevine Bridge, which strained and twisted against the flood currents. Colonel Barton Alexander of the Corps of Engineers looked on with concern as water washed over the floor planks of the wobbly bridge. The rough logs of the corduroy approaches to the bridge were mostly afloat, tenuously held together by tree stumps and grapevines wrapped around the bridge timbers.

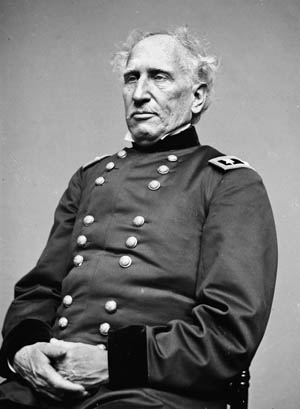

Sumner was not a man to fret over a nervous engineer’s forebodings. Born in Boston in 1797, he had seen extensive service on the frontier and in the Mexican War. At the Battle of Cerro Gordo in 1847, a spent musket ball struck him on the head and bounced off. From then on he was known in the Army as Bullhead Sumner. Coincidentally, one of Sumner’s daughters was married to Colonel Armistead Lindsay Long, a fellow antebellum officer who was serving as an aide to Robert E. Lee.

Sumner’s soldiers sloshed along the approaches, waist-deep in water, to the crossing. As the first men stepped onto the split-log flooring, Grapevine Bridge swayed to and fro. To the surprise of the skeptical Alexander and the relief of the soldiers using it, the bridge held. Once across, Minnesota soldiers watched Kirby’s battery roll onto the bridge, the drivers lashing their horses. Oddly, the weight of the soldiers, horses, and equipment on the planks had the effect of pressing them tightly against the supports, stabilizing the flooring. By 5 pm Sumner’s lead division, under Brig. Gen. John Sedgwick, had joined Couch. The 8,000 men secured the position and set up a second defensive line at a right angle to the first.

Johnston was unaware of the new arrivals and thought there was only a small force of Federals remaining in the way. Whiting’s men blithely charged across an open meadow that was immediately swept by almost a dozen Union cannons. Kirby’s guns hammered the attackers, the force of the blasts pressing the gun carriages nearly to their hubs in the soft ground.

More and more Confederates poured into the fighting at Fair Oaks. Couch’s and Sedgwick’s men inflicted heavy losses on the Confederates, who were entangled in marshy ground. Brig. Gen. Robert Hatton was mortally wounded leading his brigade. Another brigade commander, James Johnston Pettigrew, was shot and captured. A third brigadier, Wade Hampton, was shot in the foot. Hampton refused to get off his horse, choosing to stay in the saddle while Surgeon E.S. Gaillard finished extracting the musket ball from his foot. A few minutes after finishing the operation Gaillard was hit in the right arm by a bullet, a wound that would cost the surgeon his arm.

It was now clear to Johnston that the troops he had intended to throw into the fighting at Seven Pines needed to remain at Fair Oaks. Pushing the enemy out of the way would be impossible before sunset. Johnston ordered his regiments to stay where they were during the night. About 7 pm a Minie bullet struck Johnston in the right shoulder while he was inspecting the lines. A few moments later a shell exploded and drove a fragment into his chest. The bullet wound was not serious, but the shell fragment injured a lung and cracked a couple of Johnston’s ribs. The stricken commander was being placed in an ambulance when Davis and Lee arrived on the scene. Davis asked Johnston if there was anything he could do for him. Somewhere between the spot where he was wounded and the ambulance, Johnston said, he had lost his sword, a treasured family heirloom that his father had carried during the Revolution. Davis would not permit the ambulance driver to leave until the sword was found and returned to the general’s side.

Johnston’s Incapable Replacement

During the night the woods were alive with soldiers of both armies searching for dead or wounded comrades. Soldiers slept wherever they could while rain drizzled down on them. Lieutenant William N. Wood of the 19th Virginia, like many Confederates, found himself forced to camp in standing water. “I broke off small pines and piled them up,” wrote Wood, “until I had a superb bed in the midst of muck and mud. Very few found a place on which to build a fire large enough to set a tip cup in which to make coffee.”

At Fair Oaks, Brig. Gen. William H. French was awakened at 2 am on June 1 by Colonel Edward E. Cross of the 5th New Hampshire. Cross told the general that in all the disorganization after the battle ended, three Confederate regiments had unwittingly bedded down in woods only 100 yards from the right flank of French’s division. French quietly shifted his regiments to face the enemy. He didn’t want to risk a night attack, but his men captured a few stray soldiers and a courier. By the time the sun rose the next morning the rest of the Confederates were gone.

Many Federals worked all night on their fortifications. Captain George W. Hazzard worked through the dark hours trying to bring more guns to the front for Brig. Gen. Israel Richardson’s division. The guns of Sedgwick’s division, passing first, “had cut up every spot by which artillery could move without first constructing corduroys,” Hazzard complained. West of Grapevine Bridge Hazzard found 200 yards of water, 18 inches deep. Adding to his problems, “the corduroy was floating on the surface of the water, and two ambulances had been abandoned in the roadway.” Late in the night an infantry lieutenant arrived with a 44-man work detail but without either lamps or tools. They were no help. Hazzard managed to get a new corduroy road built, and three batteries were dragged out of the swamp to Richardson’s front by 4:30 am.

Gustavus Smith replaced the wounded Johnston as leader of the Army of Northern Virginia. Suddenly confronted with the burden of command, Smith was nearly paralyzed with anxiety and indecision. Thinking—or hoping—that the enemy had been driven back from Seven Pines, Smith decided to press the attack another day. He wanted Longstreet to remove his forces from the Confederate right and center and cross behind the battlefield to attack Fair Oaks. Such a complicated maneuver, Longstreet warned, was impossible to make efficiently through the swampy woods and brush at night, and it would leave the new Confederate right vulnerable. Instead of a full attack, Longstreet ordered D.H. Hill to make a limited advance against the enemy lines at Fair Oaks.

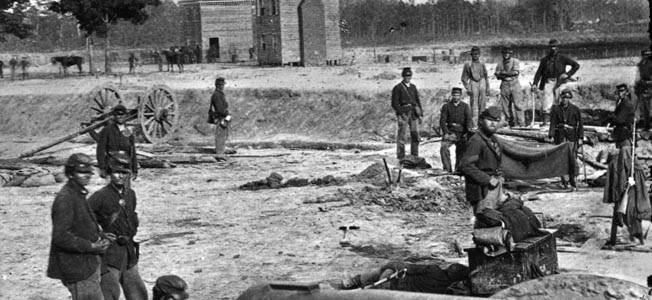

At 6:30 am the brigades of Brig. Gens. William Mahone and Lewis Armistead hit French’s Federals along the railroad tracks at Fair Oaks. As the fighting spread, more units were fed into the clash. Union Brig. Gen. Oliver O. Howard lost his right arm during the heavy fighting. In a more comical interlude, French fell headfirst into a deep mud puddle. Angry and spluttering, the general was fished out amid the exploding shells and shrieking bullets. Although confined to a relatively small section of the field, the fighting was heavy and intense. Greatly aiding the Union troops were the guns that had so laboriously been pulled through the swamps during the night. The Confederate attacks, launched without overall planning or coordination, were easily repulsed.

By early afternoon it was apparent to the Confederate commanders that the half-hearted offensive operations were a tragic waste of lives. At dawn on June 2 the Confederates pulled back from the battlefield to their old lines outside Richmond. Struggling on the boggy ground and without adequate bridges to bring reinforcements across the Chickahominy, McClellan was unable to unite his army to inflict a decisive final blow against the retreating army.

Seven Pines or Fair Oaks?

Fittingly, for a military action with so much confusion and so many mistakes, the battle came to have two names. Confederates referred to the clash as Seven Pines, the site of their successes during the battle. On that portion of the field Johnston’s men had swept the Union lines back and captured several cannons, along with more than 6,000 muskets dropped by fleeing Federals. Several days after the battle a dog with a note tied around its neck wandered into the picket line of the 33rd New York. The note said politely that the Confederates were “obliged for the tender of cannons they took from us the other day, and anything more of the same sort sent them, would be gratefully received.”

The fighting around Fair Oaks had a much different outcome. There the Union troops stood their ground and fended off the enemy. Proud of that localized success, the Union referred to the battle as Fair Oaks. Whether called Seven Pines or Fair Oaks, the two days of fighting marked the largest battle yet fought in the eastern theater of the war. Some 11,000 men were killed, wounded, or missing, most of them from the first day of the battle. There were 6,134 Confederate casualties, including 980 dead. Union losses were somewhat lighter: a total of 5,031, with 790 killed. Jesse Walton Reid of the 4th South Carolina wrote, “If this is a victory, I never want to be in a battle that is not a victory.”

On its face, Seven Pines was less a victory for the South than a draw. Federal forces had shaken off the initial impact and remained more or less in place. Still, Seven Pines altered the course of the war in the South’s favor for a time, halting McClellan’s seemingly unstoppable drive toward Richmond. It would be a long time before the Union Army would again be so close to taking the capital of the Confederacy. The most important outcome of Seven Pines came when Joseph E. Johnston’s wounds were deemed serious enough to keep him out of action for months. With Gustavus Smith proving unsatisfactory as a commander, Jefferson Davis replaced him with Robert E. Lee—one of the most impactful military appointments in American history.

It did not take Lee long to make his mark. At Mechanicsville, on June 26, he opened the first of what became known as the Seven Days’ Battles. The Confederates endured horrendous casualties, far worse than the losses at Seven Pines, but Richmond was saved and McClellan was driven back along his line of march. By September the Union Army found itself north of the Potomac again, confronting an increasingly emboldened Lee at the head of a Confederate invasion of Maryland. For the time being, at least, the momentum of the war had shifted to the South.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments