By Earl Echelberry

On March 4, 1861, with war clouds threatening the land, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated the 16th president of the United States. Then on April 12 Fort Sumter was fired upon, and the Southern Confederacy declared its independence. The war clouds had indeed burst.

President Lincoln’s response was to gather a volunteer army, with Washington as the assembling point for the newly formed regiments. In order to protect Washington from attack, the army guarded all bridges from Virginia and all other approaches to the city.

At the same time, General Robert E. Lee began to build his defenses around Richmond. Toward this end Lee assigned Colonel Philip St. George Cocke to command all approaches along the Potomac. Colonel Cocke then ordered forward, to guard the city against an early attack, troops from all portions of the South.

With the concentration of Union troops in the states adjacent to Virginia, there was every indication that the North planned to invade Virginia from several directions. The possible avenues of attack were: from Washington, along the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, toward Gordonsville, threatening the line of communication between Richmond and the western portion of the state; from Fort Monroe up the peninsula toward Richmond; through Chambersburg, Pa., into the Shenandoah Valley and the adjacent Potomac valleys to the west; from Ohio into western Virginia, by the line of the Great Kanawha Valley toward Staunton, and simultaneously from Wheeling and Parkersburg along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad eastward to Grafton, and thence southeastward to Staunton.

The Plan to Subjugate Virginia

Of the four corridors, it was from Washington toward Richmond that Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott and President Lincoln expected to overrun and subjugate Virginia. This plan’s objectives were to move directly upon the capital of Virginia and of the Confederacy, and also provide protection for Washington against a possible attack by the Confederacy.

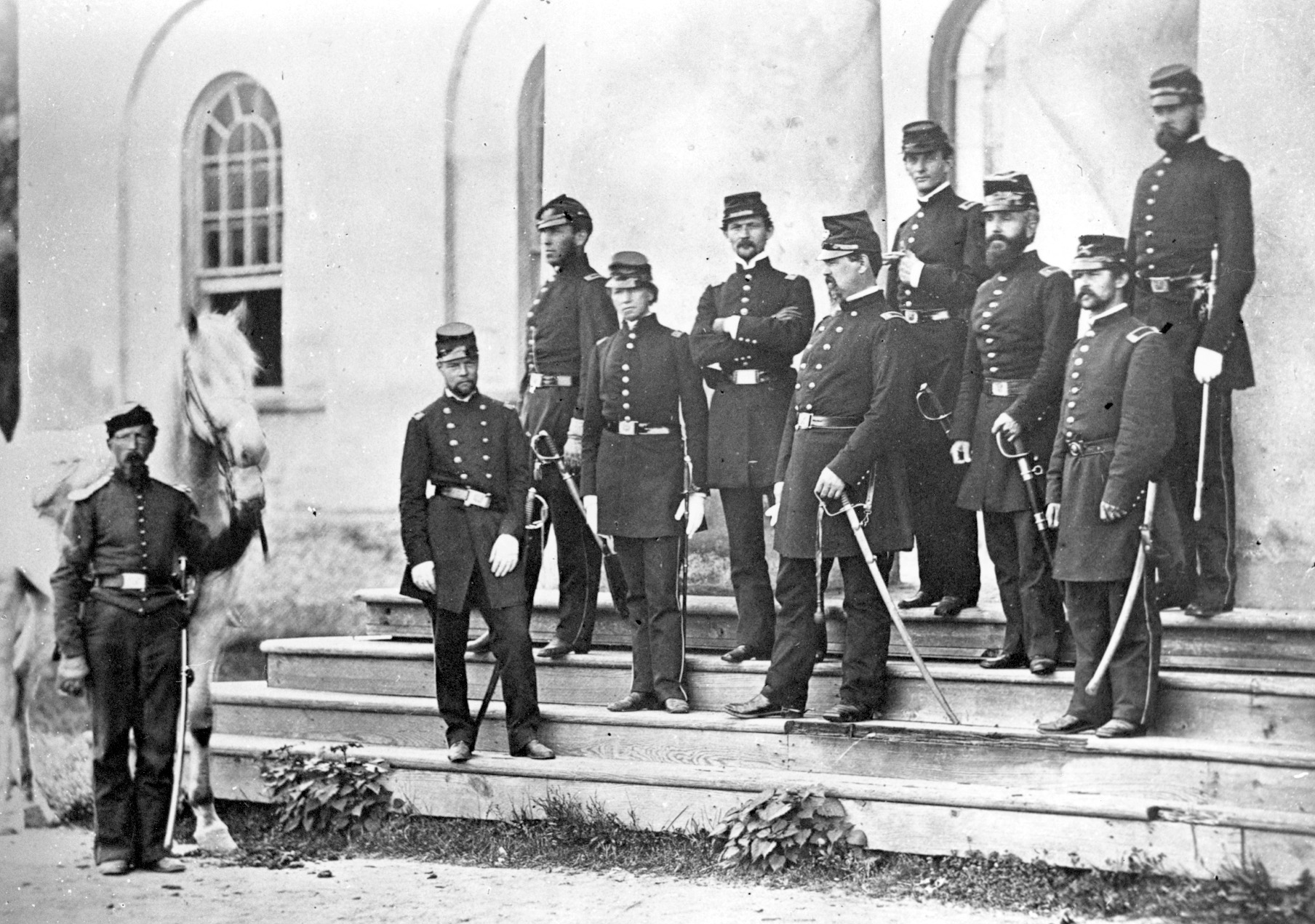

When General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard took command at Manassas, General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah served as his left flank. On his right flank at Aquia Creek on the Potomac River was a Confederate force of some 2,500 men under Brig. Gen. Theophilus Hunter Holmes. Also, there were two small advanced outposts established by Beauregard: One at Leesburg under Colonel Eppa Hunton was responsible for watching the fords of the upper Potomac east of the Blue Ridge Mountains; the other was at Fairfax Court House, which provided a direct observation of the Union Army in Washington. There were also detachments on the railway line leading toward Alexandria from Washington, and to the south guarding the approaches to the right from Alexandria.

From information he deemed reliable, Beauregard concluded that Union General Irvin McDowell had a fully equipped army of 50,000 men. To oppose this force he could field barely 18,000 men and 29 guns. Thus, Beauregard urged President Davis to converge the armies of Johnston and Holmes with his at Manassas Junction. His plan was to be ready to fall upon McDowell’s flanks, rear, and line of communication, cutting off his line of retreat and forcing him to surrender. However, Richmond did not view these suggestions favorably.

Opening Movements

On July 15, a Southern spy informed Beauregard that the Union Army was about to march on his position. Beauregard ordered his outposts back to Manassas Junction, informing President Davis. He strongly suggested to Davis that he order the Army of the Shenandoah and General Holmes’ Brigade to reinforce his Army of the Potomac at Manassas. Davis agreed and promptly ordered Holmes to report to Beauregard, and gave Johnston discretion to move his command for the same purpose.

On the afternoon of Tuesday, July 16, McDowell began marching toward Manassas Junction. With an army of poorly trained and inadequately equipped men, led mostly by mossback old-timers and inexperienced amateurs, he crossed the Potomac River into Virginia, moving westward toward Fairfax Court House and Centreville. His advance was unopposed and that night his command encamped in front of Fairfax Court House.

Advancing again on the 17th, after covering 20 miles in two days, he reached the vicinity of Centreville, and late that day the banks of a stream called Bull Run. With the first stage of his plan completed (clearing the Confederates from their positions at Fairfax Court House and Centreville), he was ready to launch his offensive against Manassas Junction. The second stage of this offensive was to force a withdrawal of the Confederate army camped behind Bull Run. From Centreville, part of the Union force would move on the Confederate Army thought to be camped behind Bull Run, near the town of Manassas Junction. Another Federal column would attempt to outflank the Rebels, cut their main line of supply from Richmond, and force their withdrawal toward the Rappahannock River.

For McDowell’s plan to work, Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson had to keep the Confederate forces under Johnston in the lower Shenandoah Valley occupied. By doing so Johnston would be unable to send reinforcements to aid in defense of Manassas Junction. However, the cavalry screen left by Johnston deceived Patterson, and Johnston began the reinforcement of Beauregard on July 18.

Mitchell’s and Blackburn’s Ford

On the morning of Thursday, July 18, General McDowell massed his army around Centreville, with the exception of a division which he left at Fairfax Court House, and headed south toward Richmond.

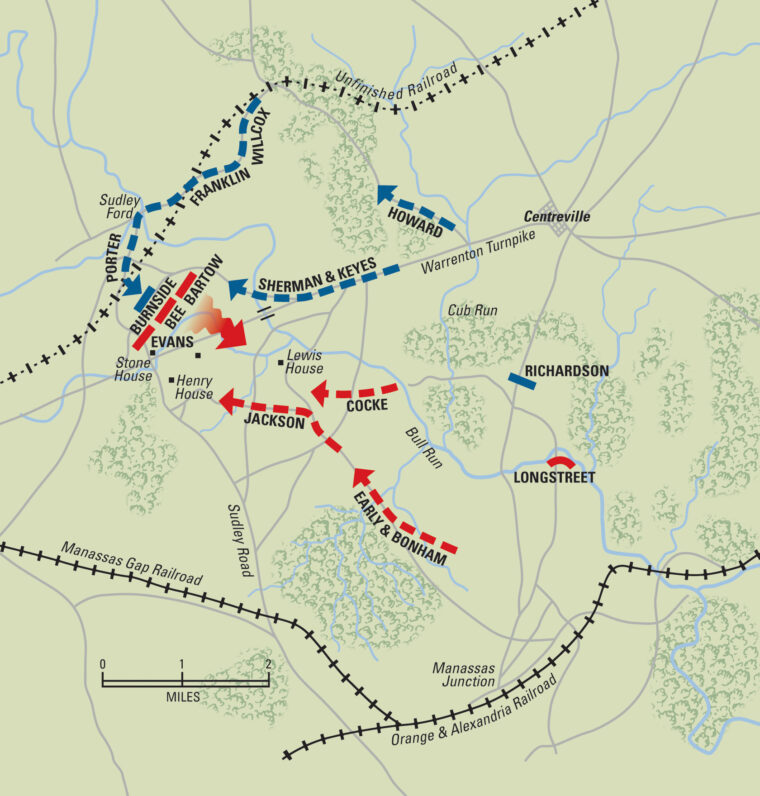

Beauregard established Bull Run as his line of defense. He distributed his Army of the Potomac along the run, from Union Mills where the Orange and Alexandria Railroad crossed the stream to the Stone Bridge where the Warrenton Turnpike crossed, an interval of about eight miles. Along this expanse of the run, it was steep and rocky with deeply wooded banks forming an almost impassable barrier to troops, except at the fords, which were a mile or two apart. Therefore, needing only to cover the fords, Beauregard organized his defense as follows:

- At the Union Mills Ford, on his extreme right, beyond the railway bridge, he placed General Richard Ewell’s 2nd Brigade, supported by that of Holmes, which had arrived from Aquia Creek.

- At McLean’s Ford, about two miles farther up the stream, was General D.R. Jones’ 3rd Brigade, supported by Colonel Jubal Early’s 6th Brigade.

- At Blackburn’s Ford, one mile farther up, was General James Longstreet’s 4th Brigade.

- At Mitchell’s Ford, about a mile farther upstream, was Brig. Gen. Milledge Luke Bonham’s 1st Brigade, which was to cover another ford about three-quarters of a mile still farther up and near the mouth of Cub Run.

- Colonel Cocke’s 5th Brigade covered Island, Ball’s, and Lewis Fords.

- Half of Colonel Nathan Evans’ 7th Brigade, under Cocke’s command, extended the Confederate line up to the Stone Bridge where the Warrenton Turnpike crossed from Centreville.

- Finally, Beauregard placed in reserve the brigades of the Army of the Shenandoah that had already arrived as follows: Colonel Bartow’s 2nd Brigade and General Barnard Bee’s 3rd Brigade were positioned between McLean’s and Blackburn’s Fords (covering the rear of Generals Bonham, Longstreet, and Jones); General Thomas Jackson’s 1st Brigade was placed between Blackburn’s and Mitchell’s Fords, (covering the rear of Generals Longstreet and Bonham).

Early on the morning of July 18, Union General Daniel Tyler cautiously began to advance his division in order to feel out the Confederate positions. There were several roads, both public and private, that led to Bull Run from Centreville. One was the Warrenton Turnpike, crossing at the Stone Bridge; another led to Mitchell’s Ford; and still another led to Blackburn’s Ford.

Tyler followed the road leading toward Blackburn’s Ford. He took with him Colonel Israel Bush Richardson’s Brigade, a squadron of cavalry, and Captain Romeyn Beck Ayres battery. At Blackburn’s Ford, General Beauregard, who had been informed of all of McDowell’s movements, had ordered up from Manassas North Carolina and Louisiana troops. The woods being so thick, his force was mostly concealed, except for one battery that was placed on open elevation.

Hoping to draw their fire and discover their position, Tyler placed Ayres’ battery on a commanding hill, and the battery opened fire. At the same time, Richardson sent forward the 2nd Michigan Regiment as skirmishers. They became engaged in a severe contest. In support of this advance, the 3rd Michigan, 1st Massachusetts, and 12th New York were pushed forward, and these, too, were soon fighting severely. Then the cavalry and two howitzers were sent forward, and these were furiously assailed by musketry, along with heavy enfilading fire from a concealed battery.

After what seemed an eternity, General Longstreet called for support from Early’s 6th Brigade. This brigade, comprising the 7th and 24th Virginia Volunteers and Colonel Harry T. Hays’ 7th Louisiana, was eager and ready for action. The 7th Louisiana, having already pocketed 40 rounds of ammunition and pinned strips of red flannel to their shirts to identify themselves as Confederates, was bursting with pride. They were eager to enter the fray under the watchful eye of their commanding general.

Commands were quickly shouted around camp, and in an instant the brigade was up and racing down the hot, dusty road toward the sound of the firing. As they crested the hill, all thoughts of glory were soon dispelled when they walked headlong into a stream of stumbling, bloodied soldiers returning from the battle. Some were clutching shattered limbs and gaping wounds, but in unison they urged the brigade on.

The shoring up of Longstreet’s faltering line began with the arrival of Early’s men and two guns of the Washington Artillery. With the additional firepower the skirmish degenerated into an artillery duel, with the Confederate guns answering round for round. Satisfied that the Confederate position was impenetrable, McDowell ordered the Union forces to fall back to Centreville.

Matthews Hill

The skirmish at Blackburn’s Ford convinced McDowell that he could not force a crossing of Bull Run. He therefore spent July 19 and 20 reconnoitering the Confederate front. His reconnaissance confirmed that an attack on the Confederate front would not be prudent, but that he could successfully cross the run above the Confederate front. By doing so, he could destroy the Rebel Army by smashing its left flank and steamrolling down the length of Beauregard’s line. He therefore resolved to attempt to turn the Confederate left, driving them from the Stone Bridge, thus forcing them from the Warrenton Turnpike. This would also sever the link, the Manassas Gap Railway, between Beauregard’s and Johnston’s armies, thereby preventing Johnston from reinforcing the larger force.

McDowell, however, was unaware that Johnston’s forces were already arriving at Manassas Junction. Thus, by the 20th Johnston’s force of 8,340 men and 20 guns, along with Holmes’ 1,265 men and six guns were in place. Beauregard positioned these new troops on the Confederate left-center and left. He placed most of his own army on his right-center and right. It was his belief that McDowell, who was Beauregard’s classmate at West Point, would use his main force to strike at Union Mills, attempting to turn his right flank.

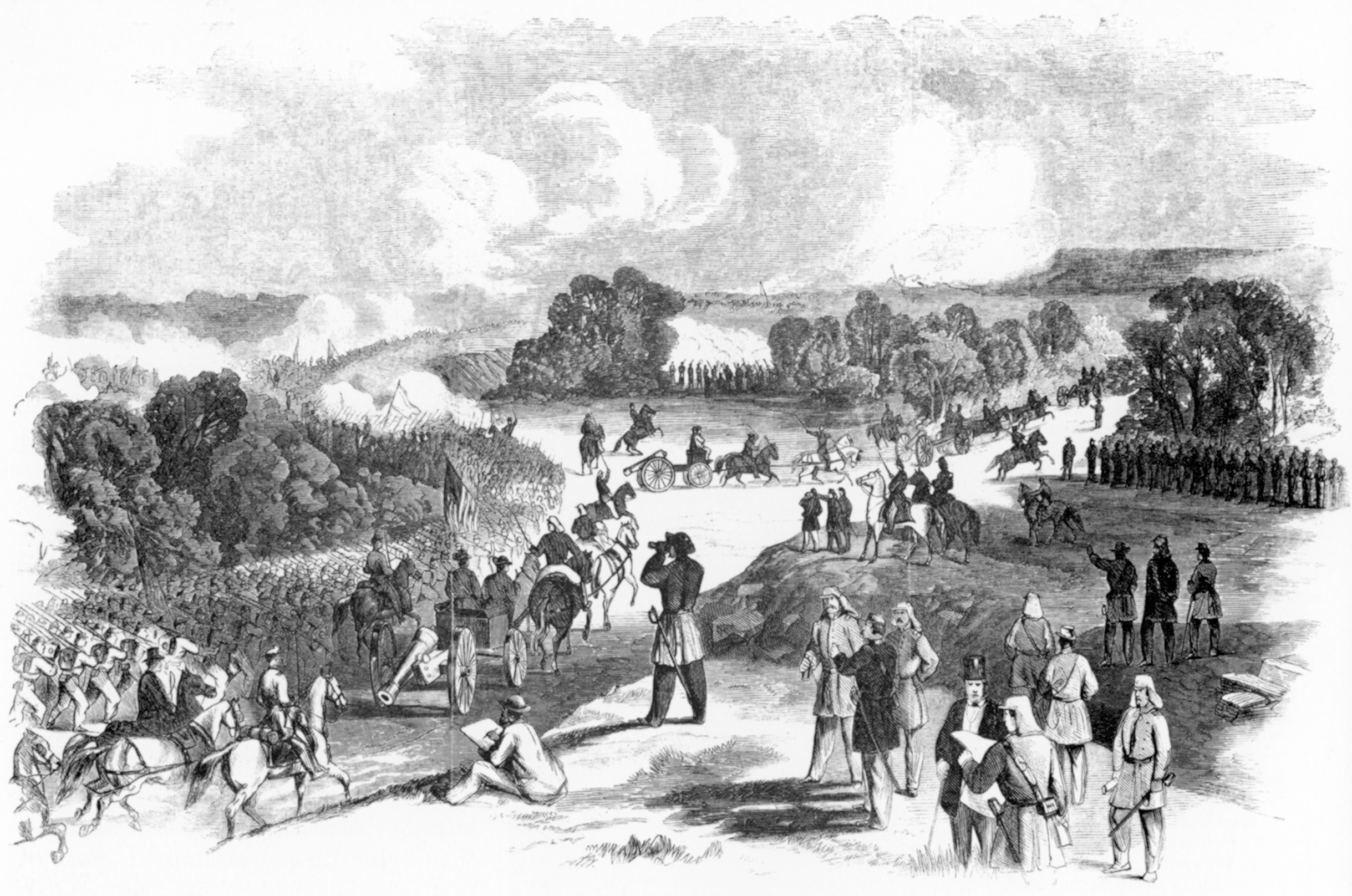

On the morning of the 21st, McDowell launched a two-pronged attack. The 2nd Division, under Colonel David Hunter, formed the main attack. With Colonel Ambrose Burnside’s and Colonel Andrew Porter’s Brigades in the lead, they splashed across Bull Run at Sudley Ford, well to the north of Beauregard’s defensive positions. From there, they turned southward on Sudley’s Spring Road and attacked the Confederates’ left flank. Colonel S.P. Heintzelman’s 3rd Division followed and reinforced the 2nd Division.

As the main attack was moving into position, Tyler’s 1st Division made a feint attack at the Stone Bridge, occupying the Confederates’ left and allowing Hunter to get in their rear unopposed. They began their advance along the Warrenton Turnpike, with Schenck’s Brigade moving to the left and Sherman’s Brigade posted to the right. When in position, Schenck’s artillery opened fire on the Confederate left, menacing the battery stationed at the Stone Bridge. Sherman was to support Schenck and to be ready to cross Bull Run, as circumstances might permit.

Tyler Spread Artillery Fire Across Evan’s Position

To meet this Union attack, Beauregard had only Cocke’s 5th Brigade in position. The Confederate forces were caught badly out of position, spread over a six-mile front with most troops on the right, where Beauregard was convinced that the main Union blow would fall.

Guarding the Confederate left at the Stone Bridge was Major Roberdeau Wheat’s Battalion and the 4th South Carolina Volunteers. Before daybreak on Sunday, July 21, South Carolina pickets heard the low rumble of a massive troop movement beyond the bridge. Quickly Colonel Evans sent one company of Wheat’s Battalion and some of his Carolinians across the creek as skirmishers. The rest of the brigade took up positions on nearby hills overlooking the bridge. Tyler’s 1st Division, advancing by way of the Warrenton Turnpike, arrived on site and began pressuring the Confederates. Tyler moved his artillery into position and began sporadically shelling Evans’ position. Because Evans’ guns were short range, they did not return fire. Failing to elicit a reply from the Confederate guns, McDowell suspected that the Confederates were concentrating their forces to strike his left wing. To guard against this, he held Colonel Oliver Howard’s Brigade in reserve. Howard would then move forward in support of Colonel Dixon Miles and Colonel Israel Richardson, if the Confederates attacked the left wing of the Union forces.

Schenck’s skirmish line advanced and engaged the Confederates. This diversion did not deceive Evans and Wheat, however, for they could see a huge dust cloud boiling up across Bull Run, slowly snaking beyond the Confederate left. In a hurried strategy session, the two Confederate officers determined that McDowell was attempting a flanking maneuver and agreed that their only option was to split the brigade. The Carolinians would remain to hold the bridge while Wheat’s Tigers sidestepped almost a mile upstream to try to hold back the enemy long enough for Beauregard and Johnston to send help.

In the meantime, the main Federal column continued its flanking movement at Sudley Ford. McDowell, fearing that Beauregard was sending reinforcements, began issuing orders for a rapid advance. Once the brigades of Burnside and Porter had forded Bull Run they began to deploy, facing southward. Immediately behind were the brigades of Colonels W.B. Franklin and Orlando B. Wilcox, accompanied by the batteries of Ricketts and Arnold.

At this junction, there was only Evans’ small, two-regiment brigade to meet the dangerous Union thrust that threatened to turn the lightly held Rebel left. Earlier, Evans had informed Cocke of the Union movement on their left flank, and his movement of troops to meet this threat. Leading six companies of the 4th South Carolina riflemen and Wheat’s battalion of Louisiana Tigers, along with two 6-pounder howitzers, he crossed the valley of Young’s Branch to the high ground called Matthews Hill. Here he stationed his men to meet the Federal advance as it moved along the Sudley Road.

“The Balls Came as Thick as Hail”

After getting into position, Wheat aligned his men perpendicular to the stream in a rolling field interspersed with patches of trees. As Wheat’s Catahoula Guerrillas were deploying as skirmishers, Union General Burnside’s Brigade slipped through the forest with bayonets brightly reflecting the morning sun. Sporadic fire broke out along the line as Burnside’s men unexpectedly flushed out the Catahoula boys. Individual shots soon merged into long, roaring volleys as the rest of Burnside’s line and six of his artillery pieces joined the fight. “The balls came as thick as hail,” wrote one Guerrilla, “[and] grape, bomb and canister would sweep our ranks every minute.”

Outnumbered six to one, Wheat’s men desperately hugged the ground or took cover behind scattered trees and answered the fire as best they could. Although hard pressed, this small force was able to hold Burnside’s men at bay. The 4th South Carolina and two artillery pieces reinforced Wheat, and the Confederates eventually drove the Union attack back.

Beauregard, in the meantime, began to reposition his troops. He ordered General Thomas Jackson’s 1st Brigade, Captain John David Imboden’s Virginia battery, Major J.B. Walton’s battery, and the brigades of General Barnard Bee and Colonel Francis Bartow to move to the left to support Cocke.

Burnside’s entire brigade, supported by eight guns, was sent forward in a second charge. Crucial minutes elapsed as the Louisianans and Rhode Islanders were locked in a deadly duel. Their battle lines surged back and forth across the rolling hills. As the Union numbers began to increase, they slowly forced Evans’ men back.

Bee moved to the left following the sound of conflict, and took up position on Henry House Hill to the south of the Warrenton Turnpike. From this hill, he had visual command of Stone Bridge and the Sudley Road where it crossed the Turnpike. Bee received a request for aid from Evans, while his artillery was pouring fire upon the Federal batteries opposed to Evans. He advised Evans to withdraw to Bee’s position on Henry House Hill.

With some of his men, Wheat began to drift to the left in the confusing retreat. Planning to make a stand around a field of haystacks, Wheat attempted to rally his men. As his soldiers began to respond to his call, there was a sickening thud of lead hitting flesh. Wheat collapsed, drilled through the body by a ball. His men, refusing to abandon him, made a litter and hustled him to safety.

Not Men Fighting, But Devils

Although Wheat and Evans’ 11 companies were steadily being pushed back, they maintained order and effectively slowed the advance of about 13,000 Yankees. The wounding of Wheat seriously threatened this resistance, however, for without effective leadership, Wheat’s battalion quickly disintegrated, and the men began to drift away in small groups to continue the fight alone or attached to other commands.

Seeing the growing confusion in the Confederate ranks, the Union soldiers began pressing their attack with increased vigor. Still full of fight, Evans was unwilling to retreat and renewed his appeal for reinforcements.

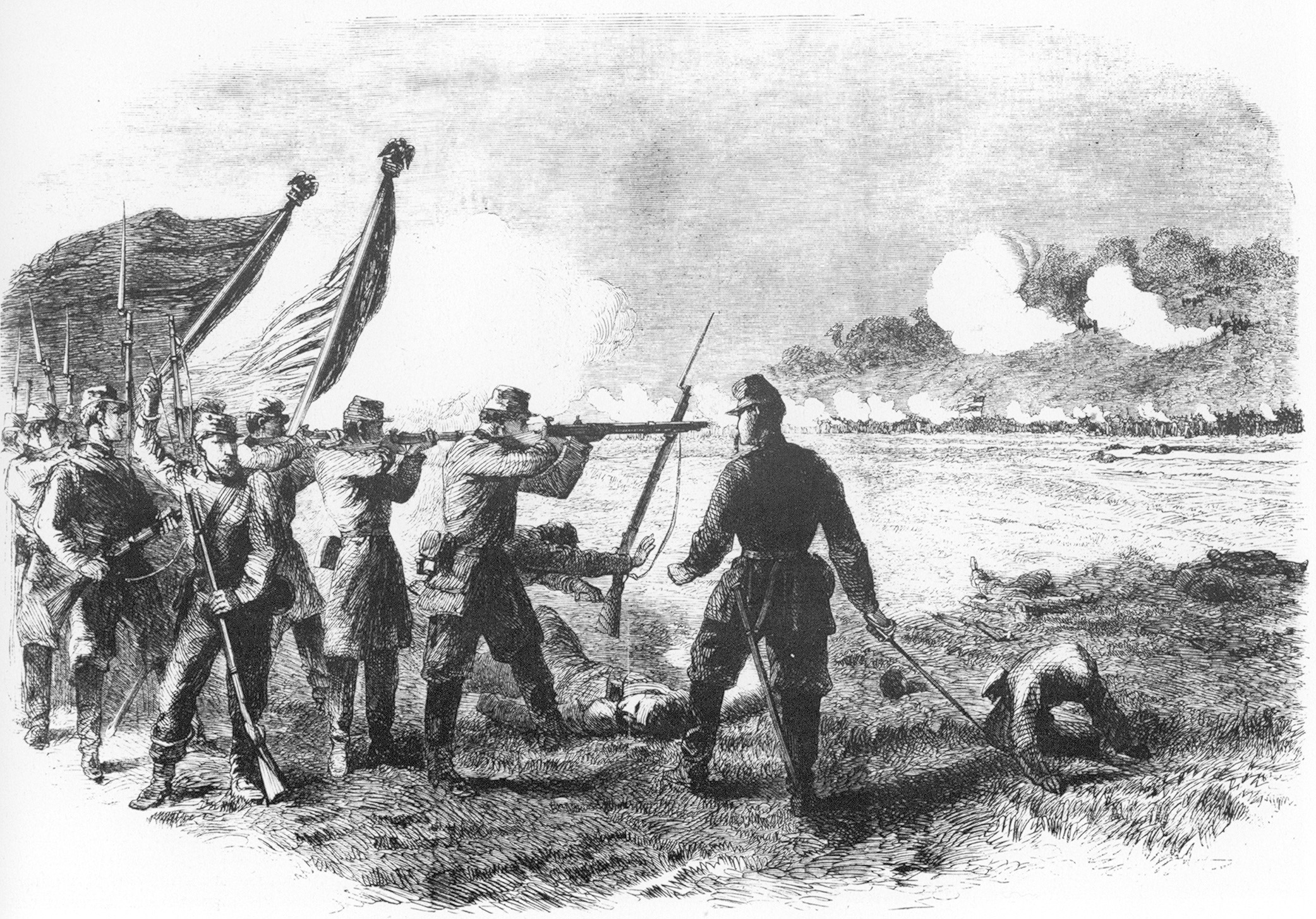

Bee, seeing the swelling numbers of Burnside’s advance, led two brigades across the valley. With the aid of the two newly arrived Confederate brigades under Bee and Bartow, the Tigers rallied, turned, and met this new Union charge. One survivor of the carnage that followed wrote, “I have been in battles several times before, but such fighting never was done, I do not believe as was done for the next half-hour, it did not seem as though men were fighting, it was devils mingling in the conflict, cursing, yelling, cutting, shrieking.” It is during this phase of the battle that the Tigers earned their reputation as fierce fighters. Even with the superior numbers of the Federal infantry, Burnside failed to make any headway against this stubborn vanguard.

In the meantime, Burnside called for help. Colonel Andrew Porter, whose brigade was marching down the Sudley Spring Road, immediately supplied it by sending a battalion of regulars to his aid. Burnside, now reinforced by eight companies of United States regular infantry and six pieces of artillery, and supported by other regiments of Porter’s Brigade, advanced in a third attack. The din of battle became deafening. The battle raged on until Porter directed a punishing fire on Evans’ left, making the whole column waver and bend.

Under orders from McDowell, Union brigades led by Colonels William Tecumseh Sherman and Erasmus D. Keyes crossed Bull Run just above the Stone Bridge, and moved on the Confederates’ rear to force the Stone Bridge. Menaced by these fresh troops on his right, heavily pressed by Burnside on his center, and terribly galled by Porter on the left, Evans gave way. Finally, the Federal fire became so fierce and heavy that it threw the Confederate line into confusion, and they were forced to withdraw their remaining troops across Warrenton Turnpike. Evans, Bee, and Bartow then moved their men up the lower slope of Henry House Hill.

Henry House Hill

By late morning, the Federals had clearly gained the upper hand. The leading brigades had shoved aside the badly mauled troops of Bee, Bartow, and Evans, and heavy Union reinforcements led by Sherman, Franklin, and others had advanced across the Turnpike and were heading up Henry House Hill. With the Federal infantry came powerful artillery support—20 or more guns commanded by a pair of daring and able officers, Captains Charles Griffin and James B. Ricketts. They deployed their cannon near the crest of the hill and began pounding the Confederate line.

Realizing the extent of the threat to his left, Beauregard began to send more reinforcements in that direction. The brigades of Holmes and Early and two regiments of General Bonham’s Brigade, with six guns, moved rapidly to the left to reinforce Evans and Bee. To hold the Union troops in their front and make demonstrations toward Centreville, Beauregard held Ewell, Jones, and Longstreet in their assigned positions on his right flank and along the center.

These orders given, Generals Pierre Beauregard and Joseph E. Johnston rode rapidly to the field of conflict. They arrived at Henry House Hill, just as the discomfited men of Bee and Evans began their retreat. Hampton Legion was the first of the reinforcements to arrive, and they began to cover the rear of the retreat. General Thomas J. Jackson’s men formed a line to right and rear on Henry Hill.

The Union in battle array came sweeping down the slope on which Evans had so long detained them, crossed Young’s Branch and the Warrenton Turnpike, and began climbing the northern slope of Henry House Hill. The Federal forces were now in possession of Warrenton Turnpike from near the Stone Bridge westward, which was one of the objectives of the movement against the Confederate left. Nevertheless, there was a formidable obstacle in the way of the complete execution of their design. The Confederates were now on a commanding plateau, too near the turnpike and the bridge for the Union to attempt to strike the Manassas Gap Railway. To drive the Confederates from the plateau was the task now immediately at hand!

The field officers of the commands of Evans and Bee were making desperate efforts to rally their men and reorganize them, but to no purpose, although Johnston and Beauregard had joined in the effort. Strong masses of Federal infantry were rapidly advancing, and disaster seemed imminent. Bee, exhausted in his fruitless effort to rally his men, rode up to Jackson, who was steadily holding his brigade in a full fronting position, and cried out in a tone of despair: “General, they are beating us back!” Jackson replied calmly, “Then we will give them the bayonet.”

Jackson’s Stonewall Brigade

Jackson’s blazing and defiant look, his bold and prompt determination, and the steady line of brave men that supported him gave new life to General Bee. Galloping back to his disorganized command, he shouted, waving his hand to the left: “Look! There is Jackson, standing like a stonewall. Rally behind the Virginians! Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer. Follow me!” Obedient to this distinct call to duty, several of Bee’s men rallied and followed him in a charge to the left against the advancing enemy. Bee was fatally felled by a ball, however, and his charge faltered. But general rally held. And his words also had their mark—from that time forward, Thomas Jackson became, and will continue to be, “Stonewall” Jackson, and his brigade the “Stonewall Brigade.”

But there was not a moment to lose. At this critical point of the battle, Beauregard ordered the regimental standards advanced some 40 yards to the front of the still-disordered commands of Evans and Bee. The field officers, thus gaining the attention of the men and inducing them to obey orders, promptly rallied on their colors. At about this time, Johnston and Beauregard advanced to the front with the colors of the 4th Alabama. Beauregard later reported, “The line that had fought all the morning and had fled, routed and disheartened, now advanced again into position as steadily as veterans.”

Seeing the superior numbers of the enemy advancing, Beauregard persuaded Johnston to ride back about a mile to the Lewis House and hasten forward the reinforcements. Providentially for the Confederates, Brig. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith’s brigade of 1,700 fresh and rested soldiers, the last of the available reinforcements from the Army of the Shenandoah, had just reached Manassas Junction by rail. In addition and also by rail, the 6th North Carolina had just reached Manassas Junction. Six miles in the rear of the battle, officers of the general staff guided and hurried them to the critical point of the pending contention—the Confederate left of the field. With these reinforcements, Beauregard’s Army was increased to 25 regiments from the 12 with which he had begun the battle. These forces were all concentrating on the right and rear of McDowell’s forces.

Beauregard then placed Colonel William Smith’s 49th Virginia and the 7th Georgia on Jackson’s left. Hampton’s Legion of South Carolinians and Hunton’s 8th Virginia were placed in the rear of Jackson’s right to oppose any attack from the direction of the Stone Bridge. With 6,500 men and 13 field guns in place, he awaited the attack of four Federal brigades. Some 11,000 Federal soldiers were now nearing the front of his position on the Henry plateau.

In a well-formed line of battle, the Union troops moved toward the waiting Confederate forces. First capturing the Robinson House on the Confederate right and then the Henry House on its left-center, they quickly positioned their batteries. From these newly established positions, they began pouring a galling fire on the Confederate line. The somewhat sunken Sudley Road, along which the Union had been advancing, furnished a covered way up the Henry House Hill, which their infantry took advantage of in the support of their batteries.

The lines of battle were now not far apart on the undulating Henry plateau. The Confederate batteries began cutting fearful gaps in the oncoming lines, while all the while receiving a steady and punishing fire from both the left and right. Two companies of Captain James Ewell Stuart’s Cavalry, sneaking around the right flank, charged through the Federal ranks along Sudley Road, adding to the havoc wrought by the Confederate infantry and artillery.

McDowell continued to extend his right with fresh bodies of infantry and artillery as they came forward from the rear, and by so doing threatened to turn Beauregard’s left. The Union boldly moved some of its guns to the front, allowing men from the 33rd Virginia to spring forward and capture them.

Union Troops Rushed in to Push the Confederates Back

Looking from his commanding position northward, Beauregard saw the constant and steady forward movement of Federal reinforcements. Immediately he reorganized his line of battle to receive this assault. The attack soon came, with fresh Union troops sweeping down the slopes from the north, crossing the valley of Young’s Branch, and pressing up the northwestern slope of Henry House Hill. After reaching the crest by the force of numbers, they pressed the Confederates back across the plateau, regaining their lost position and recapturing their lost guns.

The conflict had become a death struggle for the possession of Henry House Hill. McDowell’s advantage of numbers allowed him to extend his line and threaten to turn Beauregard’s left as well as his right.

Beauregard determined to take the offensive to meet this threatened attack on his left. Even though the Bee, Bartow, Evans, and Hampton commands, which had been fighting continuously since the early morning, were by now nearly exhausted, they responded with spirit and speed, striking the Federal left. With strong and steady blows, Jackson pierced the center, while Smith’s Virginians and Colonel Lucius J. Gartrell’s Georgians charged on the right. This bold movement, sweeping over both infantry and artillery, entirely cleared the plateau of Federal troops and captured the batteries of Captains James B. Ricketts and Charles Griffin. The Confederates cheered the success of this brilliant counterstroke.

Later General Beauregard was to write of this event: “The movement was made with such keeping and dash that the whole plateau was swept clear of the enemy, who were driven down the slope and across the turnpike on our right and the valley of Young’s Branch on our left, leaving in our final possession the Robinson and the Henry houses, with most of Ricketts’ and Griffin’s batteries, the men of which were mostly shot down where they bravely stood by their guns.”

Federal Retreat

This successful Confederate charge did not reach McDowell’s right, which extended through the woods to the west of Sudley Road and to some distance beyond Beauregard’s left. The 2nd and 8th South Carolina, moving from the Confederate right on Bull Run, were sent by Johnston to the Confederate left. They reached the field in time to meet McDowell’s movement from the right. Preston’s 28th Virginia and Colonel James L. Kemper’s Virginia Battery also appeared in time to join the South Carolinians in holding with hot contention Howard’s Brigade, Sykes’ Battalion of regulars, and the accompanying artillery and cavalry of McDowell’s right. However, they did not have the strength to drive the Union force back.

Just as Colonel Smith’s 4th Brigade entered the woods to the left of Sudley Road, a Federal bullet seriously wounded Smith. The command fell to Colonel Arnold Elzey, who marched his brigade to Beauregard’s extreme left and then, moving forward, met the Union advance just coming into the open fields of the Chinn Farm.

At the same time, on his left flank, McDowell was making another strenuous effort to turn the Confederate right flank by sending Brig. Gen. Erasmus D. Keyes’ Brigade across the Turnpike near the Stone Bridge, and thence southward, under cover from the Henry House plateau, to a favorable point for attack. Latham’s battery aided by Captain Ephraim G. Alburtis’s battery was in position to guard this flank, and met the advance with a galling fire. Thus the Confederates successfully repulsed this movement, demonstrating to McDowell that it was useless to attempt to turn Beauregard’s right.

The woods on McDowell’s right were now swarming with Confederates, who were pouring destructive volleys of musketry and cannon shot upon him. Still unwilling to yield the field, McDowell formed a new line of battle, formidable in number and in length, and crescent in outline, across Sudley Road on the heights to the north of the turnpike. Throwing forward a strong line of skirmishers, he assaulted Henry House plateau a third time. His intention was quickly thwarted by the fierce combat that Colonel Arnold Elzey was now pressing on his right, the force of which was intensified by the arrival of Early’s grand Virginia Brigade from McLean’s Ford. Early’s Brigade, sweeping around the rear of the woods through which Elzey had passed, bore down upon the flank of an already-wavering Union right and started that wing in full retreat. Learning of the success on his left, Beauregard sent orders all along the line for a common charge on McDowell’s left. This drove the already-yielding Union lines from the field of contention, causing them to break to get beyond reach of the Confederate fire. This sudden, unexpected, heavy, and overpowering blow resulted in an absolute and uncontrollable Union rout.

As regiment after regiment gave way and hurried toward the rear in confusion, others seized with panic joined in the race from danger. Muskets, knapsacks, and other equipment littered the ground as the Yankees threw away their gear in their haste to escape. The Union Army was in flight!

Beauregard’s Pursuit

Beauregard ordered all the troops on the field to pursue the retreating enemy. Bonham’s Brigade advanced, with instructions to strike the enemy at the crossing of Cub Run, about midway between the Stone Bridge and Centreville, while Longstreet’s Brigade crossed at Blackburn’s Ford with instructions to strike the enemy at Centreville. Obstructions in the road to Cub Run diverted Bonham toward Centreville, so both brigades ended up seeking the same objective and came under the command of Bonham, the ranking officer. Their line of march led through the abandoned Federal camps.

At this junction Bonham issued orders to stop the pursuit. The reason was that while the Federal right was in full retreat, Beauregard received word that a large Federal force had broken through the Confederate right of the Bull Run line and was moving on the depot of supplies at Manassas Junction. Beauregard took the brigades of Ewell and Holmes and prepared to defend against this threatened counterstroke of the enemy. At the same time, he recalled all troops engaged in the pursuit to come to his assistance.

Longstreet described the situation as follows:

“When within artillery range of the retreating column passing through Centreville, the infantry was deployed on the sides of the road, under cover of the forests, so as to give room for the batteries ordered into action in the open, Bonham’s brigade on the left, Longstreet’s on the right. As the guns were about to open, there came a message that the enemy, instead of being in precipitate retreat, was marching around to attack the Confederate right. With this report came orders, or report of orders, for the brigades to return to their positions behind the run. I denounced the report as absurd, claimed to know a retreat, such as was before me, and ordered the batteries to open fire.”

Nearing McLean’s Ford where the expected Federal attack must come, Beauregard discovered it was Jones’s Brigade that was recrossing the run from an advance under earlier orders. These troops were mistaken for Federal troops crossing at McLean’s Ford and someone rushed and reported to headquarters of a Union advance. It was now nearly dark and too late to resume the interrupted pursuit of the retreating army. Thus the golden opportunity for completing the victory by following up the rout of the Federal army was lost.

2,000 Southern Soldiers Lost

When darkness and confusion in the Confederates’ ranks finally ended the chase, the exhausted but ecstatic Rebels halted and huddled around sputtering campfires to recount their day’s experiences. Both sides had about 18,000 men engaged in the bloody day’s work, with the South losing approximately 2,000.

After caring for the needs of his men, Beauregard rode to his headquarters near Manassas Junction where, at about 10 pm, he found President Davis and General Johnston. Davis had arrived at the battlefield in time to witness the last of the Union force retreat across Bull Run. The next morning, in recognition of this magnificent victory, Beauregard received a commission as full general in the Confederate States Army, dated July 21, 1861.

From Centreville, at 5:45 pm on the 21st, General McDowell telegraphed General Scott:

“We passed Bull Run. Engaged the enemy, who, it seems, had just been reinforced by General Johnston. We drove them for several hours, and finally routed them. They rallied and repulsed us, but only to give us again the victory, which seemed complete. But our men, exhausted with fatigue and thirst and confused by firing into each other, were attacked by the enemy’s reserves, and driven from the position we had gained, overlooking Manassas. After this the men could not be rallied, but slowly left the field. In the meantime the enemy outflanked Richardson at Blackburn’s ford, and we have now to hold Centreville till our men can get behind it. Miles’ division is holding the town.”

Later, from Fairfax Court House, he telegraphed:

“The men having thrown away their haversacks in the battle and left them behind, they are without food; have eaten nothing since breakfast. We are without artillery ammunition. The larger part of the men are a confused mob, entirely demoralized. It was the opinion of all of the commanders that no stand could be made this side of the Potomac. We will, however, make the attempt at Fairfax Court House. From a prisoner we learn that 20,000 from Johnston joined last night, and they march on us to-night.”

Early the next morning, from Fairfax Court House, he again wired:

“Many of the volunteers did not wait for authority to proceed to the Potomac, but left on their own decision. They are now pouring through this place in a state of utter disorganization. They could not be prepared for action by to-morrow morning even were they willing. I learn from prisoners that we are to be pressed here tonight and to-morrow morning, as the enemy’s force is very large and they are elated. I think we heard cannon on our rear guard. I think now, as all of my commanders thought at Centreville, there is no alternative but to fall back to the Potomac, and I shall proceed to do so with as much regularity as possible.”

Remembering the Struggles of Battle

This first big military test of the East took place in the great amphitheater ringed by the hills near Manassas Junction, Va. Neither side had properly prepared its army for a full-scale battle; consequently, the fight at Bull Run had comic-opera as well as tragic aspects. What at first looked like a Northern victory turned into a dispiriting defeat as reinforcements under Joseph E. Johnston joined the troops of Beauregard and routed the Yankees under Irvin McDowell.

Manassas was a memorable Southern victory. The following is the address published by Generals Johnston and Beauregard to thank the soldiers for a “glorious, triumphant and complete victory.”

“One week ago, a countless host of men, organized into an army, with all the appointments which modern art and practiced skill could devise, invaded the soil of Virginia. Their people sounded their approach with triumphant displays of anticipated victory. Their Generals came in almost royal state; their Ministers, Senators and women came to witness the immolation of our army and subjugation of our people, and to celebrate the result with wild revelry.

“It is with the profoundest emotions of gratitude to an overruling God, whose hand is manifest in protecting our homes and liberties, that we, your Generals commanding, are enabled, in the name of our whole country, to thank you for that patriotic courage, that heroic gallantry, that devoted daring, exhibited by you in the actions of the 18th and 21st, by which the hosts of the enemy were scattered, and a signal and glorious victory obtained.

“The two affairs of the 18th and 21st were but the sustained and continued effort of your patriotism against the constantly recurring columns of an enemy, fully treble your numbers; and these efforts were crowned, on the evening of the 21st, with a victory so complete, that the invaders are driven disgracefully from the field, and made to fly in disorderly rout back to their entrenchment’s—a distance of over thirty miles.

“They left upon the field nearly every piece of their artillery, a large portion of their arms, equipments, baggage, stores, etc., etc., and almost every one of their wounded and dead, amounting, together with prisoners, to many thousands. Thus, the northern hosts were driven from Virginia.

“Soldiers! We congratulate you on an event, which ensures the liberty of our country. We congratulate every man of you, whose glorious privilege it was to participate in this triumph of courage and of truth—to fight in the battle of Manassas. You have created an epoch in the history of liberty and unborn nations will rise up and call you ‘blessed.’”

“Continue this noble devotion, looking always to the protection of a just God, and before time grows much older, we will be hailed as the deliverers of a nation of ten millions of people.

“Comrades! Our brothers who have fallen have earned undying renown upon earth, and their blood shed in our holy cause is a precious and acceptable sacrifice to the Father of Truth and Right.

“Their graves are beside the tomb of Washington; their spirits have joined with his in eternal communion.

“We will hold fast to the soil in which the dust of Washington is thus mingled with the dust of our brothers. We will transmit this land free to our children, or we will fall into the fresh graves of our brothers in arms. We drop one tear on their laurels and move forward to avenge them.

“Soldiers! We congratulate you on a glorious, triumphant and complete victory and we thank you for doing your whole duty in the service of your country.”

The Federals withdrew toward Washington, and Beauregard went into camp at Centreville, where he undertook to train further his relatively raw Confederate soldiers.

Good article with detail. Recommend you always have a caption for each picture so the reader knows what it is about.