By Roy Morris, Jr.

Two days after the unparalleled bloodletting at Antietam, a bushy-bearded Scottish photographer and his pudgy, clean-shaven assistant rolled onto the battlefield with their bulky stereoscopic cameras and portable darkroom. Forty-year-old Alexander Gardner and James F. Gibson were part of Mathew Brady’s team of field photographers.

To this point in the war, the photographers had mainly snapped pictures of generals, cannons, tents, bridges, houses, wagons, rivers, creeks and horses. It was almost like a giant summer camp. After Gardner and Gibson had finished taking 70 photographs at Antietam, no one would ever make that mistake again.

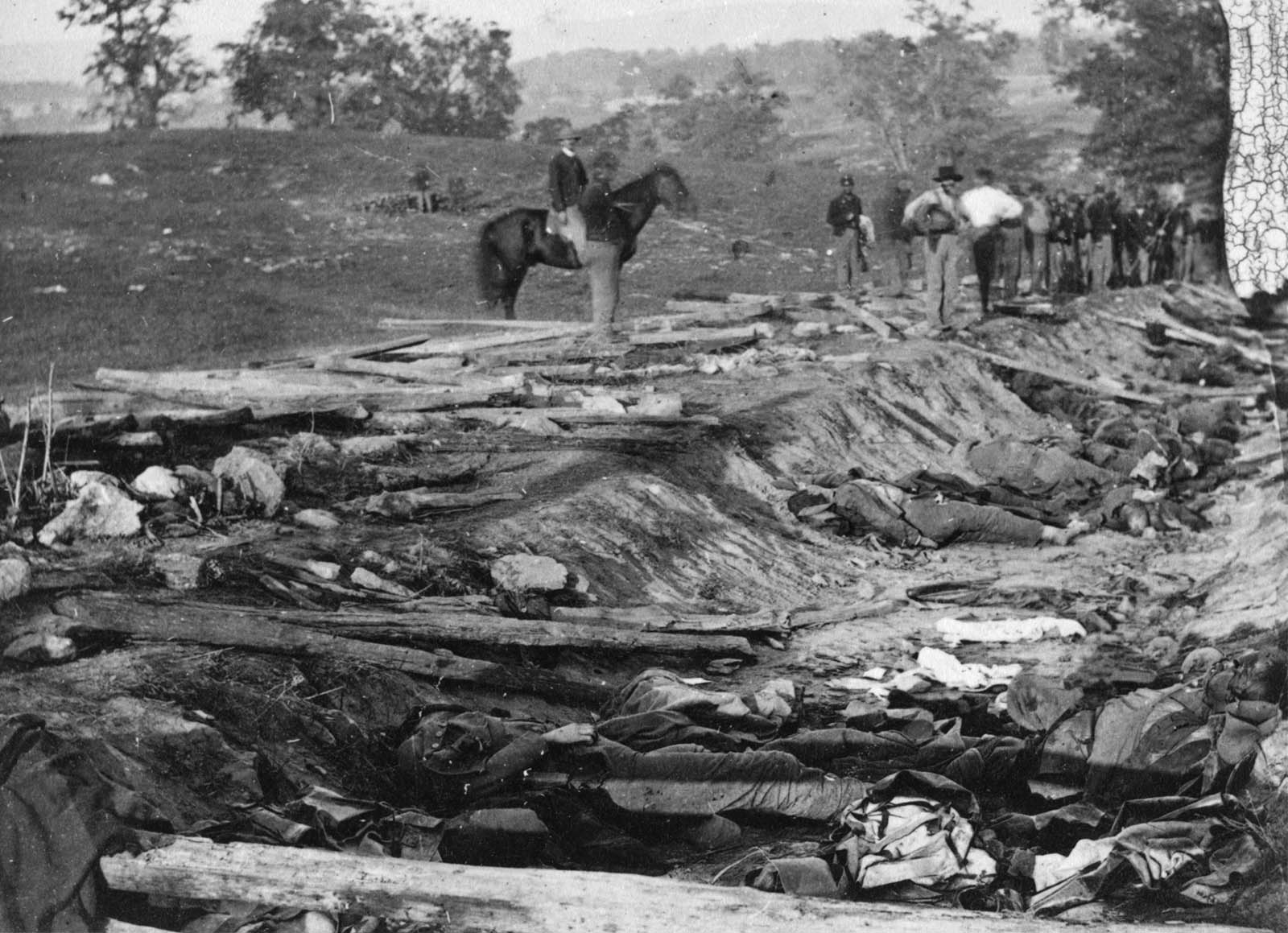

The Maryland battlefield, controlled by the Union forces of Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac, was nothing less than a charnel house. Per longstanding military tradition, the victorious army had the responsibility of caring for the wounded and burying the dead of both sides (the defeated army, having retreated, could scarcely be expected to help). By the time Gardner and Gibson began taking photographs on September 19, most of the 2,100 Union dead had been buried, but the 2,700 slain Confederates remained lying for the most part where they had fallen, many in the sunken roadway known, without exaggeration, as “Bloody Lane.” Others lay crumpled behind a wooden fence alongside the Hagerstown Turnpike.

The photographers spent their first two days at Antietam photographing the Confederate dead, many of whom belonged to Brig. Gen. William Starke’s Louisiana Brigade, known as the Tigers. Prior to Antietam, the Tigers had been known more for their boisterous, hard-drinking antics in camp than their prowess on the battlefield. Gardner and Gibson would pay mute tribute to their valor and sacrifice. In death, they had more than lived up to their nickname.

Wherever they turned, the photographers found scenes of horrific slaughter, as exhausted members of the burial parties were hard-pressed to keep up with the demands of their terrible task. The weather, warm and sunny, did nothing to help. The broiling sun hastened the decomposition of the swelling, fly-covered bodies, making the job of retrieval and burial even more repulsive. Meanwhile, thousands of wounded soldiers suffered in makeshift field hospitals, often within yards of the bloated dead.

In all, Gardner and Gibson spent four days at Antietam; the final two days they concentrated on the battle on the Union right at the already famous Burnside Bridge. Gardner sent an understated telegram back to his assistant, David Knox, at Brady’s Washington, D.C., studio: “Got forty five negatives of battle. Tell Jim please deliver as soon as possible.”

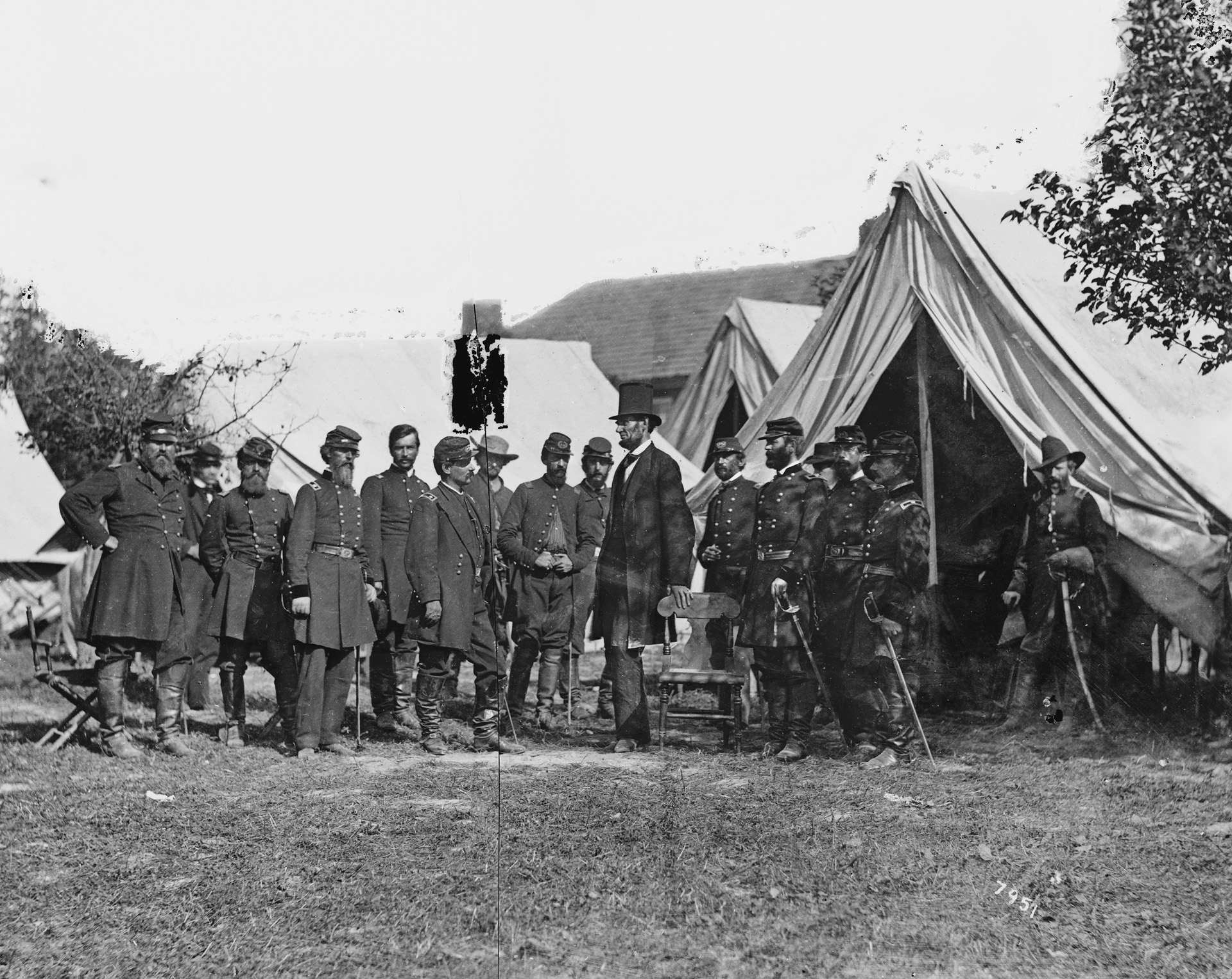

Gardner would return to the battlefield on October 3-4 with President Abraham Lincoln, taking another 25 prints while the president attempted unsuccessfully to get McClellan to follow up his ghastly victory. Later that same month, Mathew Brady displayed the Gardner-Gibson photographs in his New York studio, where they created a sensation. Thousands flocked to see the first-ever photographs of dead Americans on a battlefield. Said an unnamed reporter for the New York Times; “Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along streets, he has done something very like it.” The face of war had suddenly become real.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments