By Arnold Blumberg

On March 8, 1864, a rainy Tuesday, President and Mrs. Lincoln held a reception at the White House in Washington. This in itself was not unusual; such events were weekly occurrences. What made this reception different was that, as announced earlier in the National Republican Newspaper, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was to be the guest of honor.

“Three Cheers For Grant”

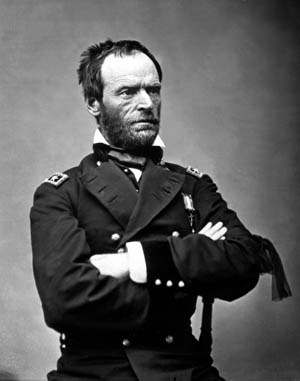

The general had arrived in the nation’s capital that afternoon after being summoned by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Grant had spent the last several days on a train transporting him to Washington from his military headquarters in Nashville. He was accompanied by two staff officers, Brig. Gen. John A. Rawlins and Lt. Col. Cyrus B. Comstock, and his 14-year-old-son, Fred. An official delegation was supposed to meet Grant upon his arrival but somehow failed to do so. While the two staff officers went directly to the War Department to report that Grant was in town, the general and his son walked to Willard’s Hotel, two blocks from the White House, to inquire about lodgings.

Willard’s was the best known hotel in the city. It was normal to see civilian and military celebrities conducting government business in the hotel lobby and bar. So many high-ranking Army officers had frequented the place during the past three years that the nondescript, soft-spoken Grant appeared to be just another dime-a-dozen general traveling through Washington on his way home or back to the front. One regular at the hotel described Grant as having the look “of a man who did, or once did, take a little too much to drink.” The registration clerk must have had the same impression. When the general, who was wearing a plain linen duster that hid his uniform, inquired about the availability of accommodations, the clerk replied with patronizing indifference. He offered Grant a cramped room on the top floor. Grant said that would be fine and signed the register.

The clerk’s demeanor changed in an instant when he glanced at the signature written on the hotel register: “U.S. Grant and Son, Galena, Illinois.” The clerk suddenly realized that the dusty general who appeared so seedy to one onlooker was the most successful Union battlefield commander in the war. Hotel management hastily offered the new arrival the bridal suite on the second floor, and the clerk personally carried the Grants’ bags up to their lodgings for them.

Coming back down to the dining room, Grant caused a stir as people began to look his way and whisper excitedly to one another, “There’s Grant!” Some stood up and hammered on tables, shouting, “Grant, Grant, Grant!” The call went up: “Three cheers for Grant!” Grant rose, fumbled with his napkin, and humbly bowed to all points of the compass. Unable to eat because so many people were swarming around him vying for his attention, Grant and his son left the dining hall and returned to their room.

Reviving the Rank of Lieutenant General

By this point in the war, every endeavor Grant had undertaken—from Belmont, Missouri, to Forts Henry and Donelson, Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga—had ended in victory. The recent improbable triumph at Chattanooga had prompted the New York Herald to proclaim, “Grant is one of the greatest soldiers of the age, without an equal in the list of generals now alive.” The cover of the February 6 issue of Harper’s Weekly featured an elaborate Thomas Nast illustration showing the figure of Columbia pinning a gold medal on the general’s chest, accompanied by the simple inscription, “Thanks to Grant.”

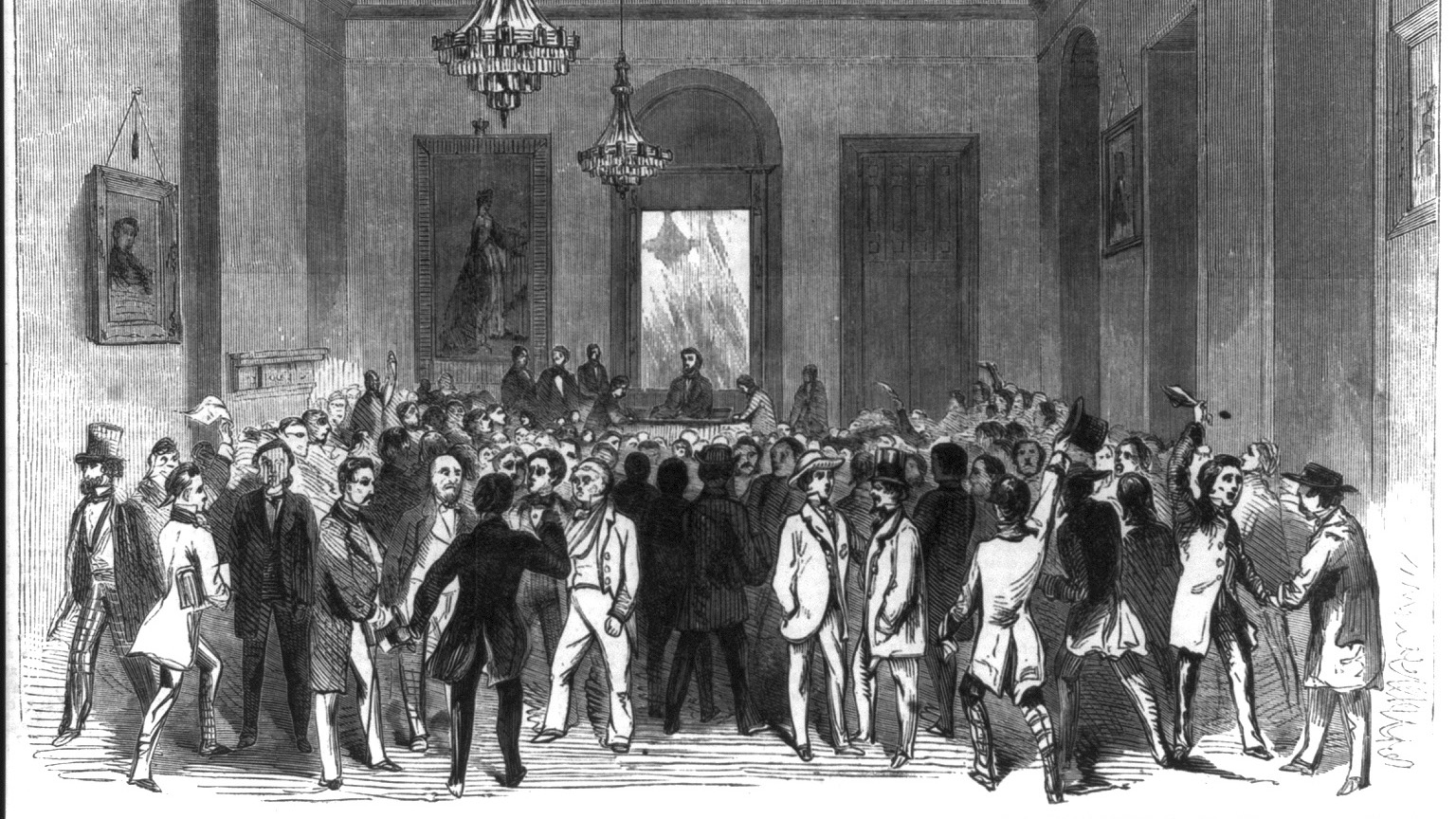

National politicians were not far behind in recognizing Grant’s value. When Congress convened in December 1863, the House of Representatives issued a unanimous proclamation thanking Grant and his Army of the Tennessee for their recent victories and calling for a gold medal to be struck in the general’s honor; the Senate added its endorsement. On December 7, Grant’s longtime political patron, Illinois Congressman Elihu B. Washburne, announced that he would introduce a bill authorizing the president to revive the rank of lieutenant general. Everyone understood that Grant was the only candidate for the post. When some in the House counseled waiting until the war was over before bestowing the honor, Washburne thundered, “I want it conferred now!” Washburne’s words silenced any further opposition.

When Washburne informed Grant of his scheme, Grant responded to his political mentor in writing that he did not “ask or feel that I deserve anything more in the shape in honors or promotion.” However, he did not reject the promotion out of hand. He hoped that he could remain in the West while Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, a trusted subordinate and adviser of Grant’s since early 1862, might take charge of the Army of the Potomac in the Eastern Theater.

Grant For President?

Rumors of Grant’s elevation prompted some opponents of the Lincoln administration to suggest that Grant should become a candidate for president in the upcoming national election. The pro-Democrat New York Herald proclaimed, “The next president must be a military man.” The Herald’s editor, James G. Bennett, who hated Lincoln, pushed the idea of Grant running on the Democratic ticket in November. Bennett pronounced the general “the people’s candidate” and praised Grant as “the man who knows how to tan leather, politicians, and the hides of rebels.”

Although Grant was in agreement with most Republican policies, he kept his political inclinations to himself, thus prompting both parties to court him. When the idea of his running for the highest office in the land first arose after the fall of Vicksburg, Grant told Ohio Democratic Congressman Barnabas Burns that the idea “astonished him. Nothing likely to happen would pain me so much as to see my name used in connection with a political office.” In a follow-up letter to former Illinois congressman Isaac N. Morris, Grant added, “In your letter you say I have it in my power to be the next president! This is last thing in the world I desire. I would regard such a consummation as being highly unfortunate for myself if not for the country.” To his father, Jessie R. Grant, the general vented his frustrations at the political types who were pressuring him to run for office. “All I want is to be left alone to fight this war out,” he declared, “fight all rebel opposition, and restore a happy Union in the shortest possible time.”

Talk of Grant’s presidential candidacy inevitably harmed his chances of obtaining a third star on his shoulder straps. Former Grant military aides in Washington, along with friendly political operatives, worked to quash the stories of a possible Grant run for the presidency. Washburne warned Grant of the perils: “As things stand now, you could get the nomination of the Democracy [Democratic Party],” he said, “but could not be elected against Lincoln.”

“Be Yourself—Simple, Honest and Unpretending”

As the bill for Grant’s promotion to lieutenant general progressed through Congress, Lincoln slowly but surely came around to supporting the idea. As a last measure of reassurance, Secretary of War Stanton dispatched Maj. Gen. David Hunter to Chattanooga to check out Grant’s political soundness. Hunter’s favorable report to the administration led Lincoln to back the lieutenant general bill. His decision was made easier by Hunter’s assurance that Lincoln had the unfailing support of the man he intended to name commander of all Union land forces.

On March 3, Grant telegraphed Sherman, “The bill reviving the grade of Lieutenant General in the Army became a law and my name has been sent to the Senate for the place.” Congress had passed the bill on February 29. Lincoln then submitted Grant’s name to the U.S. Senate for confirmation as his choice to fill the position. Grant went on to inform his friend that Grant had been ordered to report to Washington, and that he would be travelling to the nation’s capital the next morning. He added, “I shall say very distinctly on my arrival there that I will accept no appointment which will require me to make that city my headquarters.”

Sherman extended congratulations on Grant’s promotion and offered some advice to his commander. He said that even though Grant now had “become George Washington’s legitimate successor, and occupy a position of almost dangerous elevation,” Grant must still “be yourself—simple, honest and unpretending.” Sherman urged his chief to stick to his aim of steering clear of politics and let others deal with the War Department and Congress. He implored Grant, “For God’s sake and for your country’s sake, come out of Washington! Come out West,” reasoning that the war would be won in that theater, not in the East.

Lincoln Meets Grant

Grant’s train ride to Washington from Nashville proved to be anything but the low-key event the general had hoped. At every stop along the way large crowds gathered to see and cheer the man who seemed destined to save the Union. This not only surprised Grant but made him uncomfortable. The excitement and interest continued unabated once he checked into Willard’s Hotel. Soon after retreating to his room with his son after the chaos in the hotel dining room, Grant was visited by former Secretary of War Simon Cameron and Pennsylvania Congressman James K. Moorhead, who bustled Grant off to the reception at the White House. Either at the Grants’ hotel or near the White House, Grant was joined by Rawlins and Comstock, who had spent their time after arriving in the capital unsuccessfully hunting for Secretary of War Stanton to let him know that Grant was in town.

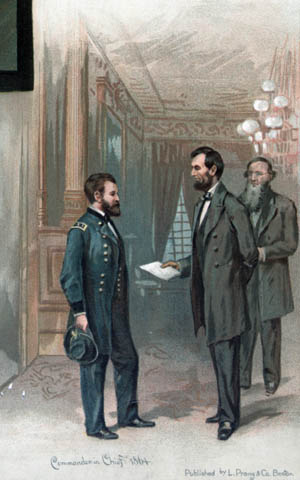

Although the night was wet and raw, a huge crowd had come to the White House in anticipation of Grant being there. As Grant entered the presidential mansion at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, the swarms of onlookers parted like the Red Sea, allowing the general to have a clear corridor through the building. A few score feet from where Grant entered stood President Lincoln. Upon Grant’s entrance, Lincoln stepped forward, a smile on his face, his hand outstretched while Grant walked toward him. One of Lincoln’s secretaries recalled that it appeared to be a “long walk for a bashful man [Grant], the eyes of the world upon him.” As the men shook hands, Lincoln exulted, “Why, here is General Grant! Well, this is a great pleasure, I assure you.”

When the handshake was finished, the two stood side by side, Lincoln at six feet, four inches looking down at the five foot, eight inch Grant as he he grasped the lapel of the general’s uniform coat. The president beckoned to Secretary of State William H. Seward, who took Grant off to present him to Mrs. Lincoln, then led Grant to the East Room, where the president and a large crowd were waiting.

As Grant came into the East Room, it signaled another outbreak of cheers; many pressed in on Grant to shake his hand. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles described the scene as “rowdy and unseemly,” while another onlooker, Barnabas Burns, said the cheering group “was the only real mob I ever saw in the White House.” Grant had to stand on a sofa for the better part of an hour to avoid being trampled underfoot by adoring fans. Brooks wrote of the event: “For once at least the President of the United States was not the chief figure in the picture. The little, scared-looking man [Grant] who stood on a crimson-covered sofa was the idol of the hour.”

With some effort Seward, aided by White House staffers, managed to extricate the distinguished visitor from the press of people who had besieged him and take him to the Blue Room, where Lincoln and Stanton were waiting. Once there, Lincoln showed Grant into a drawing room where Lincoln would present him with his new commission the next day. Lincoln explained that he would make a short speech at the ceremony—no more than four sentences—and that he wanted Grant to make a short reply. So that Grant would know what was coming, the president gave him a copy of his remarks. Lincoln went on to say that he wanted the general to include in his statement two salient points: something that would smooth over any feelings of jealousy among other general officers in the Army, and something that would put Grant “on as good terms as possible with the Army of the Potomac.”

Grant’s Acceptance Speech

At 1 pm the next day, Grant returned to the White House to receive his commission as lieutenant general in the Regular Army. To make the occasion more newsworthy, Lincoln had assembled his entire cabinet. After the president and Grant positioned themselves standing face to face, Lincoln read his brief statement: “General Grant: The nation’s appreciation of what you have done, and its reliance upon you for what remains to do, in the existing great struggle, are now presented with this great commission, constituting you Lieutenant General in the Army of the United States. With this high honor devolves upon you also a corresponding responsibility. As the country herein trusts you, under God, it will sustain you. I scarcely need to add that what I here speak for the nation goes my own hearty personal concurrence.”

Grant, holding his written notes in one hand, commenced the acceptance speech he had composed the night before in his hotel room. He appeared ill at ease as he began to read the original draft, and the first few word were almost inaudible. One listener thought Grant simply had not taken enough air into his lungs and tried to read the entire piece in one quick rush. After his poor start the general paused, tightly gripped his paper with both hands, took a deep breath, and went on in a clear voice that seemed to gain strength as he continued to speak. His comments were brief: “Mr. President: I accept this commission with gratitude for the high honor conferred. With the aid of the noble armies that have fought on so many fields for our common country, it will be my earnest endeavor not to disappoint your expectations. I feel the full weight of the responsibilities now devolving on me and know if they are met it will be due to those armies, and above all to the favor of that Providence which leads both Nations and men.”

Lincoln’s personal secretary, John Nicolay, later observed of Grant’s performance: “The general had hurried and almost illegibly written his speech on a half sheet of note paper in lead pencil. His embarrassment was evident and extreme; he found his own writing difficult to read.” He went on to say that the speech was “brief and to the point,” but noted that Grant had failed to include the two items Lincoln had requested he make in his presentation. Still, all in attendance agreed that the general’s remarks had suited the moment.

Grant’s Place in the New Military Hierarchy

After the formalities at the White House, Grant inspected the defenses surrounding Washington, posed for a picture at Mathew Brady’s famous portrait gallery, and spent some time with Lincoln and Stanton discussing his new duties. All the while Grant was itching to escape the capital. He concluded his eventful day by attending a dinner at Secretary Seward’s home.

The next day Lincoln sent orders to the War Department formally making Grant commander in chief of the armies of the United States. This created a new military hierarchy in the Federal Army: Grant became head of all the Union armies, Sherman took Grant’s place as commander of the Department of the Military Division of the Mississippi, and Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, the former Army chief, was relieved of that duty and named chief of staff under Grant. Another major change followed the shakeup of the high command: the headquarters of the new commanding general would no longer be in an office at the War Department in Washington, as it had been under Halleck, but would be wherever Grant was at the time.

Staying in the East

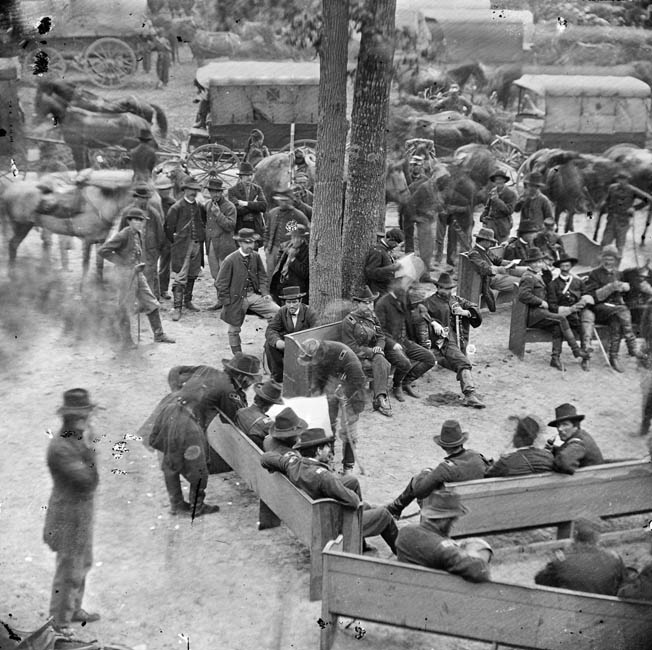

That same day Grant and Rawlins departed Washington and headed for Brandy Station, Virginia, campsite of the Army of the Potomac and its commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade. Soon after his arrival at Meade’s headquarters, Grant realized that two significant assumptions that had guided his actions had changed. In the mere 36 hours Grant had been in Washington, he came to realize that despite his sincere desire to return to the West, he needed to be closer to the seat of government. He understood that regular face-to-face meetings with the president and the secretary of war would do more to facilitate the war effort than impersonal telegrams. Also, his presence in the East would ease the vexing problem and practices of army administration departments such as quartermaster and ordnance that consistently acted contrary to the needs of the field armies. Lincoln seemed like a reasonable politician who would not intrude into matters beyond his understanding. Had not the president just told him during their last conversation that he did not expect the general to share his military plans with him? All Lincoln wanted, he made clear to Grant, was that Grant take personal responsibility and act decisively.

Grant had a second change of heart after his first meeting with Meade. A number of his former military subordinates, including Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson and Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana, had recommended that Meade be removed from command of the Army the Potomac if that organization was to perform at its full potential. Upon meeting Meade, Grant was impressed by the former’s offer to step down as army commander and serve in a subordinate capacity if Grant wanted a Western general, such as Sherman, to take charge of the Army of the Potomac. Grant recorded in his memoirs that Meade’s unselfish offer “gave me even a more favorable opinion of Meade than did his great victory at Gettysburg the July before.” In addition, contrary to what Grant had been led to believe, Lincoln and Stanton were not eager to remove Meade from command and did not blame Meade for the army’s lackluster performance up to that time. They placed that blame on Halleck, who had laid down the rules and objectives under which Meade’s army had been operating. Grant decided to retain Meade in command.

A Common Sight in Washington

After his visit with Meade, Grant returned to Washington on the 11th and met again with Lincoln and his cabinet. Secretary Welles observed that Grant now appeared more calm and businesslike than before, but that he was still lacking in military bearing and dignity. Meanwhile, Sherman sent more reminders to his commanding officer and friend to beware of political intrigues festering in Washington and again begged Grant to return to the West as fast as he could.

After informing the administration of his intention to control the nation’s armies from the Eastern Theater and make his field headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, Grant announced that he would be leaving that night for Nashville to meet with Sherman and other principal Western generals to discuss the upcoming military campaign. At the same time he would put his personal affairs in order and move his family east.

Before Grant could depart Washington he had to fend off Mrs. Lincoln’s insistence he remain in town for a banquet in his honor on the 12th. Grant held firm to his plan to leave for Tennessee, describing the last three days as “the warmest campaign I have ever witnessed during the war.” Although appreciating the “honor Mrs. Lincoln would do me,” he told the president, “Time is very important now. And really, Mr. Lincoln, I have had enough of this show business.” It was a mark of Grant’s growing confidence that he felt safe in refusing the formidable and capricious First Lady’s invitation. Lincoln’s reaction was unrecorded.

Grant returned to Washington on March 23 from his conclave with the Western generals. Three days later he established his headquarters at Culpeper, Virginia, near but not with the Army of the Potomac. There he fine-tuned his strategy for a coordinated and sustained attack on Confederate forces by the Federal armies on May 3. During these preparations, Grant made four more trips to Washington to give the administration the barebones outline of his forthcoming military operations. While at the capital he stayed again at Willard’s, declining to work in the two-room office space set up for him at the War Department. And everywhere he went he drew enthusiastic and admiring crowds. On his last morning in Washington, as the spring campaign was about to commence, a reporter caught up with Grant as the latter was rushing from Willard’s to the train station. The newspaperman jokingly inquired if Grant intended to breakfast again until the war was over. Granted responded tartly, “Not here, I don’t.”

“Grant is the First General I’ve Had”

A few days after handing Grant his new rank and responsibilities, Lincoln was asked by William Stoddard, assistant to John Nicolay, what type of general he thought Grant would turn out to be. After remarking that wherever he was Grant seemed to “make things git,” Lincoln added admiringly, “Grant is the first general I’ve had. He’s a general.” Lincoln observed that every other military man he had previously put in charge wanted the president to approve his plans and take responsibility for the outcome of those plans. But with Grant, Lincoln declared, “He hasn’t told me what his plans are. I don’t know and I don’t want to know. I’m glad to find a man who can go ahead without me.”

When Grant came to Washington in early March 1864, he not only captured the hearts and imagination of the politicians and common people, but also the confidence, respect and fulsome support of the president of the United States. It was a singular personal and political victory for Grant, and it would lead to more victories in the future, for both him and the war-weary nation he served. Lincoln, as usual, had been right.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments