By Sheldon Winkler

During World War II, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, from her exile in London, urged her staff to find a 12-year-old Dutch boy, Dirk van der Heide. Young Dirk, who had emigrated to the United States with his nine-year-old sister Keetje, had written a short book titled My Sister and I, which was published by Harcourt, Brace and Company in New York in January 1941. A few months later the book was published in London by Faber and Faber.

Dirk, who was from the southern suburbs of Rotterdam, lived through the five-day blitzkrieg in Holland and kept a detailed diary of those troubled times. Unfortunately, Queen Wilhelmina was unsuccessful in her efforts to locate Dirk and present him with an award of some kind during her visits to the United States in 1942 when she addressed a joint session of Congress and 1943 when she visited President Franklin D. Roosevelt at Hyde Park. The reason was simple. The book was a fabrication and Dirk van der Heide did not exist.

“Something Terrible Happened Last Night. War began!!!”

The translator of the diary, Mrs. Antoon Deventer, writes that all of the names in the diary, including the author’s, were changed to protect the author’s family remaining in Holland from the risk of German retaliation. In the book’s introduction prepared by the translator, we are told that Dirk has augmented his diary since he left his homeland. Mrs. Deventer goes on to reveal that the English captain of the ship that brought Dirk and his sister to the United States, who conveniently could read Dutch, persuaded him to revise and enhance his diary. Speaking of Dirk, Mrs. Deventer admits, “Sometimes his writing seems abnormally mature,” and the “bewildered child in wartime is revealed with a direct force and clarity.”

The diary begins on May 7, 1940, when Dirk observes a number of soldiers on his way to school, some surrounding public buildings. Later that evening the radio announces that all leaves are canceled and soldiers are instructed to return to their units.

On May 10, 1940, Dirk writes, “Something terrible happened last night. War began!!!” Dirk tells about a series of German air raids that day on Rotterdam attacking unarmed civilians, beginning in the early morning. He speaks of antiaircraft fire, ambulance sirens, searchlights, fires, and the consistent loud noises of the guns and falling bombs. Radio reports call for reservists to report to their posts and his father, a veterinarian, dutifully obeys. Radio reports also tell of German parachutists, some of whom he thinks he observes as “white specks floating down” toward Waalhaven Airport, and fighting throughout the country.

The situation in Holland continued to deteriorate on May 11, 1940. Dutch citizens were asked to pile sandbags around their homes, dig trenches, and store food. Telephone service and mail delivery were terminated. German planes dropped leaflets claiming they came as friends to protect the Dutch from the British and French. Dutch radio constantly provided updates and admitted that the war was going badly.

Later that day a bomb landed on one side of the air raid shelter Dirk and his family used, did considerable damage, and caused a few casualties. Dirk reported seeing dead people being removed from bombed houses and ambulances coming and going. Late that night, Dirk’s Uncle Pieter told him his mother was killed earlier in the day when the hospital where she volunteered her services was bombed.

Escape to England and America

On May 12, rumors of the Germans using gas, exceptionally powerful bombs, and flamethrowers that emitted a long line of fire abounded. Uncle Pieter decided to try to get Dirk and his sister to England and began a perilous journey in his American Buick that day. They miraculously reached the riverside town of Dordrecht by driving south over roads filled with refugees from all walks of life trying to leave Rotterdam. The refugees walked, rode bicycles, carried children and their belongings, and pushed babies in carriages. Dutch soldiers were also traveling over the same crowded roads on their way to fight the Germans. The car passed meadows with Dutch soldiers manning antiaircraft guns. The defenders shared these meadows with spring flowers.

At 3 in the afternoon German planes attacked the road with machine guns, causing many casualties. Dirk, his sister, and Uncle Pieter got under the car along with other refugees. Many people were killed or wounded. Uncle Pieter continued the trip after the attack, driving slowly and carefully. At one time he had to get out of the car and move three dead bodies so they could get by. In Dordrecht, they finally were able to board a small boat to bring them to Vlissingen on May 13. Eventually, they left for England in an overcrowded boat on May 14. Their boat docked in Harwich the following day, and they learned that Holland had surrendered to the Germans.

Dirk and Keetje enjoyed London for several weeks. Uncle Pieter took them sightseeing, and they were impressed by the sand bags banked around the British Museum and St. Paul’s Cathedral and the trenches in the gardens at Kensington. Dirk notes that English roads are “fixed to stop Germans, with barricades, trenches, and tank traps.”

Comments about the kindness and hospitality of the British and England’s precarious wartime situation abound during Dirk and Keetje’s stay in London. On arriving at the London train station, Dirk writes, “There were many English people there to give us breakfast and to help us. They were all very cheerful and smiling.” Dirk later comments, “It is fine to be in this country where it is so quiet and peaceful the way home was.” Uncle Pieter remarks, “The fall of Holland threatens England.” A point is made about the English physician who refused to accept money when he treated Keetje when she was ill. When he is about to depart from London, Dirk writes, “I hate to leave England. I have had a good time here and I hope the Germans never do to England what they did to Holland.”

Dirk and Keetje left Liverpool for the United States on July 2, 1940, and arrived safely after a fearful voyage, with the ship successfully avoiding German submarines and mines. They were met by an aunt and uncle who lived in New York and soon were enjoying their new home.

The next diary entry is dated September 28, 1940, when Dirk writes about his happy experiences in America. Uncle Pieter’s letters tell the children that he is not able to return to Holland and is now working for the British. The children’s father writes that he is back in Rotterdam and tells of the deteriorating conditions and suffering his country is experiencing.

A Book of Questionable Authenticity

On reading the book today, the question of its authenticity is obvious. The exceptional writing, moving descriptions of events, and remarkable insights introduce doubts whether it is the work of a 12-year-old. Dirk appears to have experienced or observed every type of horrific German military action, and what he did not see he mentions and attributes to hearsay and rumor. It seems improbable that a little Dutch boy could be at the right place at the right time to go through so much misery and terror in such a short time period and record everything in a masterful way.

The propaganda aspect of the book is also obvious, with its continuing comments about Britain’s hopeless situation, the kindness and determination of the British in the midst of adversity, and the need for Britain to avoid the same fate that befell Holland. The appeal for the United States to enter the war and come to the aid of Britain is clear and continuous. The book was published too late to assist Holland, but it had the potential to help England and hasten U.S. involvement in the war.

52,000 Copies Produced

Sales of My Sister and I were far beyond Harcourt, Brace’s expectations. During 1941 approximately 46,000 copies were sold. By July 1948, when the book went out of print, more than 52,000 copies had been produced.

Reviews of the book from around the world were outstanding. The New York Times, Boston Transcript, Chicago Tribune, Manchester Evening News, and Irish Times, among others, had nothing but praise for the slim volume. Although a few critics expressed some doubts about the authorship of the book, these patriotic skeptics did not want to create any potential problems during wartime and basically kept their thoughts to themselves.

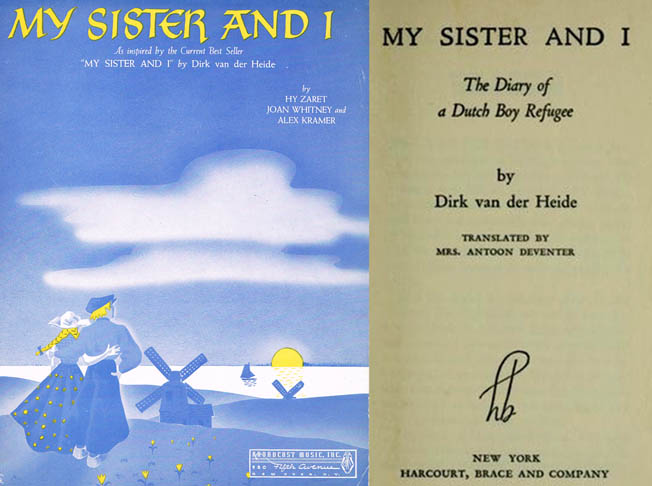

The music world was not to be left behind. “My Sister and I,” a tribute to the refugee children of Europe inspired by the best-selling book, was put to music. Recorded by Jimmy Dorsey and his Orchestra with a vocal by Bob Eberly, Nat Brandwynne and his Orchestra, the Dick Jurgens Orchestra in the United States, and Oscar Rabin and his Band with a vocal by Bob Dale in England, among others, the song was very popular during the summer of 1941. The title page of the sheet music states, “As inspired by the current best-seller My Sister and I, by Dirk van der Heide.”

The words and music of “My Sister and I” were written by Hy Zaret, Joan Whitney, and Alex Kramer and published by Gower Music, Inc., of New York. Hy Zaret, the senior author, would continue to write lyrics, the most popular of which were those to “Unchained Melody.” It is interesting to note that despite its popularity, “My Sister and I” is not mentioned in many of the standard music encyclopedias and indexes of the war years and not included in most collections of World War II sheet music. Based on the Billboard charts, “My Sister and I” was listed in the number seven position for the top songs of 1941.

The first four lines of the song’s lyrics are, “My sister and I remember still, a tulip garden by an old Dutch mill, and the home that was all our own until.., but we don’t talk about that.”

A “Shrewd British Propaganda Maneuver”

Dr. Paul Fussell, Donald T. Regan Professor of English Literature at the University of Pennsylvania and noted lecturer, critic, and historian, had doubts about the book’s authenticity. He questioned why a 12-year-old Dutch boy portrayed the British as noble, kind, and sympathetic people. Dr. Fussell noted the book’s “subtle job of black [covert] propaganda.” He hypothesized that it was a “shrewd British propaganda maneuver” beyond the capability of a 12-year-old and tried to find out as much as possible about My Sister and I. Dr. Fussell’s subsequent research was discussed in great detail in the Munro Beattie Lecture titled “Writing in Wartime—The Uses of Innocence,” which he presented at Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, in 1987.

In a visit to Faber and Faber, the British publisher of My Sister and I, Dr. Fussell found that the file on the book “had been thoroughly sanitized,” with all evidence of authorship removed and presumably destroyed. Back in New York, he visited Harcourt, Brace (at that time known as Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich), where the entire file had been removed. Dr. Fussell’s astonished company guide claimed this was a unique incident as it had never occurred previously.

The Truth Behind the Book is Revealed

Not to be discouraged, Dr. Fussell inserted author’s queries in a number of standard literary outlets requesting information about the authorship and publication of My Sister and I. One of the many respondents suggested writing to a Mrs. Stanley Young, who lived in New York State. Another response was from a woman who worked in the advertising department of Harcourt, Brace in 1941. She wrote, “Most of the actors in that comedy of errors are dead, but there are, I believe, relatives still alive and capable of kicking who might prefer to have the little hoax left buried.”

Mrs. Stanley Young (the novelist Nancy Wilson Ross) was most cooperative and revealed to Dr. Fussell that My Sister and I was written by her late husband while he was working as an editor at Harcourt, Brace. Stanley Preston Young, the true author of My Sister and I, was a noted writer and editor who at one time taught English at Williams College. He settled into publishing and held a number of positions at major publishing houses before his death in 1975.

Another participant in the story of My Sister and I was Frank Morley, the brother of novelist and essayist Christopher Morley. In 1939, he moved from London to New York to accept the position of editor in chief at Harcourt, Brace.

Fussell believes Morley returned to the United States at that time “specifically to assist the covert work of British propaganda in wearing down American neutrality.” Fussell also claims that Morley was acquainted with William Stevenson, author of A Man Called Intrepid, who directed the New York office of British Security Coordination (BSC) in Rockefeller Center.

BSC was purported to be the most intricate and integrated secret operations organization in history. One BSC’s objectives was to aid and encourage U.S. participation in World War II. Stevenson admitted in his book that BSC was “the hub for all branches of British intelligence.” However, it was not British propaganda and rhetoric that was responsible for bringing the United States into World War II, but the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent declaration of war by Germany and Italy against the United States on December 11, 1941. It is doubtful that BSC had anything to do with the musical version of My Sister and I.

Dr. Fussell concluded his lecture with the sentence, “It is all a testimony to the literary talent of Mr. Stanley Preston Young, who sensed both what the age and the United Kingdom demanded, and who supplied it in a memorable American way.”

The Lasting Lie of Dirk van der Heide

Although the true story of My Sister and I was known for almost a decade, it did not prevent Laurel Holliday, in her book Children of the Holocaust and World War II—Their Secret Dairies, from reprinting most of the diary verbatim and representing it as factual. Author Holliday’s treatise was published in 1995 by Pocket Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., for Washington Square Press as the first anthology of children’s diaries written during World War II and the Holocaust. Apparently, Ms. Holliday was completely taken in by the hoax that occurred approximately 55 years earlier. Holliday writes, “These diaries tell us what it was like for children to live each day with the knowledge that it could be their last.”

While some of the most poignant and moving contributions to World War II literature were written by young people of no literary pretensions, My Sister and I does not fall into that category.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments