By Melanie Savage

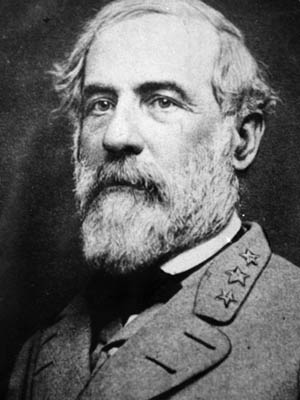

On the morning of October 17, 1859, an aide to Secretary of War John B. Floyd hurried off with an urgent message for Colonel Robert E. Lee. Floyd had just received word that the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, had been seized by a group of antislavery zealots led by the notorious terrorist John Brown. Floyd was ordering Lee to come to Washington (he was on leave at his home in Arlington, just across the Potomac River) and take command of the force being sent to Harpers Ferry to retake the arsenal and restore order to the community. Also home on leave that morning was a young cavalry officer from Virginia, 1st Lt. James Ewell Brown Stuart, nicknamed “Jeb,” who had been waiting for some time to see Floyd. The aide convinced Stuart instead to ride over to Lee’s home and deliver the peremptory orders.

Floyd needed to scrape together a body of soldiers for Lee to lead to Harpers Ferry; a daunting task, since no Army troops were readily available. President James Buchanan, normally a procrastinator, immediately realized the seriousness of the situation and demanded quick action. Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey jumped at the chance to get involved, telling his chief clerk, Charles W. Welsh, to ride over to the Washington Navy Yard and see how many Marines could be mustered for duty. Upon arrival, Welsh spoke with 1st Lt. Israel Greene, temporarily in charge of the Marine barracks. Welsh told the young Marine officer what had transpired at Harpers Ferry and directed him to gather as many men as he could for duty.

Although Greene was the senior line officer present, Major William Russell, the Marine Corps paymaster, accompanied the detachment of 86 leathernecks. Working with the major, Greene saw to it that each of the 86 men drew a full complement of muskets, ball cartridges, and rations. Since no one knew for certain the strength or exact position of the insurgents, two 3-inch howitzers and a number of shrapnel shells were also made ready. At 3:30 pm, Greene and his Marines set off by train to Harpers Ferry. At 10 that evening, Robert E. Lee and J.E.B. Stuart linked up with Russell and Greene at Sandy Hook, Maryland, just across the Potomac from Harpers Ferry.

John Brown Defeated

After a botched attempt at taking over the town and inciting a slave rebellion, John Brown and his polyglot force had seized hostages and taken refuge inside a small brick engine house on federal property. The Marines marched to Harpers Ferry, entering the arsenal grounds through a back gate. About 11 pm, Lee ordered the various volunteer units out of the grounds, clearing space for the only regular troops at his disposal—the Marines under Greene.

The following morning, Lee demanded that the terrorists surrender. When all attempts to negotiate with Brown failed, 27 Marines broke down the door with a battering ram, rushed into the building, killed or wounded the holdouts, and took Brown prisoner. Lee would later write, “I must also ask to express my entire commendation of the conduct of the detachment of Marines, who were at all times ready and prompt in the execution of any duty.”

Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry and his subsequent execution added fuel to the already simmering political fire that separated North and South. In little more than a year, with the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency, South Carolina would secede from the Union, followed by six other Southern states. With the firing upon Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, the nation would be torn apart by civil war. So, too, would be the United States Marine Corps, 20 of whose officers resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, including fully one-half of all line officers ranked from first lieutenant to major.

Originally Published in MILITARY HERITAGE magazine.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments