By Michael D. Hull

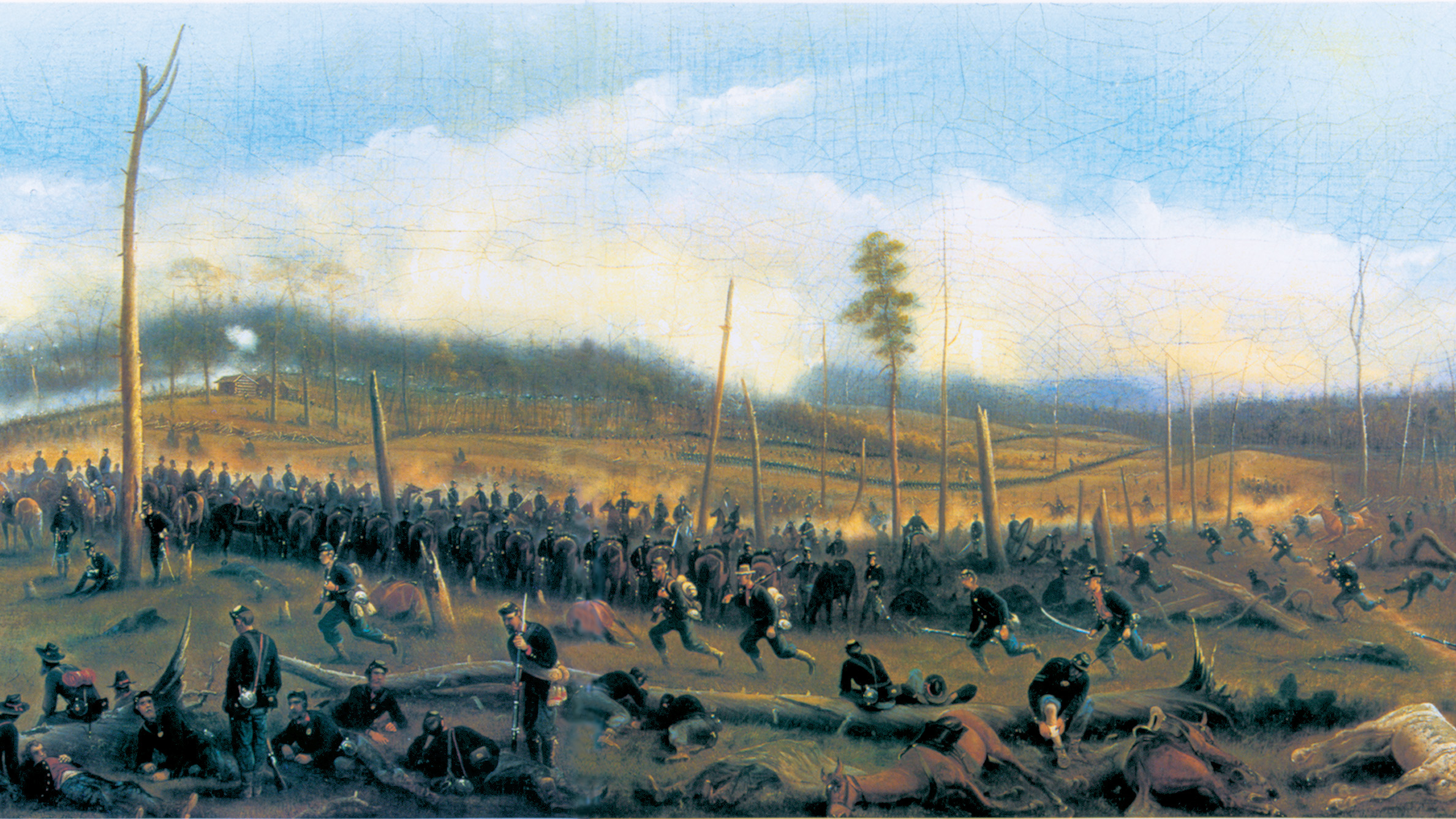

Despite their gallant service in the Civil War, on the Western frontier, and in the Spanish-American War, black soldiers were used mostly for labor and given only a limited fighting role when the U.S. Army entered World War I.

Unfortunately, African-American soldiers in the U.S. Army faced the same prospect when their country was thrust into World War II on December 7, 1941. The War Department still viewed black troops as unsuitable for combat, and again relegated them to labor and support battalions.

But, because of the constant need for manpower and spirited lobbying on the part of the black community and Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, the first lady, changes eventually came about. Late in the war, African-Americans were given a chance to prove their worth in action, including most notably the Tuskegee Airmen of the Mediterranean Air Force’s 99th Pursuit Squadron and 332nd Fighter Group, the 761st (Black Panther) Tank Battalion of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s Third Army, and the hell-bent-for-leather truck drivers of the legendary Red Ball Express.

The Army activated three “colored” divisions in 1941 and 1942—the 2nd Cavalry Division at Fort Riley, Kansas, on April 1, 1941; the 93rd Infantry Division at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, on May 15; and the 92nd Infantry Division at Fort McClellan, Alabama, on October 15. Civil-rights leaders were encouraged, but their hopes soon dwindled when the three divisions were kept undergoing endless training while white divisions shipped out for the Pacific and European theaters. It was not until 1944, a campaign year, that President Franklin D. Roosevelt began pushing the back-pedaling War Department to deploy black troops.

The 2nd Cavalry Division, which comprised the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments of frontier fame, was shipped to Oran, Algeria, in March 1944, but saw no action. It was inactivated two months later and its personnel sent to labor battalions for the duration. It was an inglorious end for the “Buffalo Soldiers.”

The 93rd Infantry Division arrived at Guadalcanal on February 7, 1944, but its elements were parceled out for defensive and labor activities for the rest of the war. Only one unit, the 24th (Separate) Regiment, saw combat. After departing from Guadalcanal on December 8, the unit landed on Saipan and Tinian in the Marianas for garrison duty. It joined black U.S. Marines in mopping up Japanese resistance and was awarded a unit commendation.

The 92nd Infantry (Buffalo) division was the only black division to see combat in Europe, and this came about because of heightened demands from civil rights leaders and a critical manpower shortage in the Italian theater during the summer of 1944. Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark’s multi-national Fifth Army had been stripped of almost 100,000 men for the Normandy campaign.

After its activation in Alabama, the 92nd Division moved to Fort Huachuca in May 1943. It took part in Fourth Army maneuvers in Louisiana in early 1944, and returned to Arizona that April. At Fort Huachuca, a 19th century cavalry post situated in southeastern Arizona, 15 miles north of the Mexican border, the men of the 92nd were led and trained by white staff officers and company commanders. They were mostly southerners.

The divisional commander was 51-year-old, Virginia-born Maj. Gen. Edward M. “Ned” Almond, a World War I infantry veteran who had taken over the 92nd in October 1942. It was said that he owed his command to his marriage to the sister of General George C. Marshall, the Army chief of staff. Energetic but tactless and dictatorial, Almond believed that he knew how to manage African-American soldiers and lacked sympathy for them.

Addressing one of his regiments, Almond said, “I did not send for you. Your Negro newspapers, Negro politicians, and white friends have insisted on your seeing combat, and I shall see that you get combat and your share of casualties.” Another white officer noted later, “He most certainly kept his word.”

The first element of the 92nd Division to go overseas was the 370th Infantry Regiment, which was shipped to the Mediterranean theater in the summer of 1944. Wearing the division’s distinctive shoulder patch bearing a black buffalo on a green background, the soldiers were raw but eager to get into action. Lt. Vernon J. Baker, a platoon leader from Cheyenne, Wyoming, said, “We were young and dumb and thought we were going to whip the Germans’ behinds and drive them back home as soon as we got there.” Baker was later awarded the Medal of Honor, upgraded from the Distinguished Service Cross, for leading an attack that wiped out six German machine-gun nests near Viareggio in April 1945.

The men of the 370th Regiment disembarked at Naples on August 1, and black soldiers in the service units on the docks cheered loudly as they filed down gangplanks. Private Edward Winn, a quartermaster, observed, “Most times you would see a black soldier, he was carrying ammunition, cans of fuel, or chow for the front line—anything but a gun. These guys were carrying rifles. A black G.I. carrying a rifle was not a normal sight to see every day in Europe in 1944.”

Three weeks later, on August 23, the regiment went into the line with Maj. Gen. Vernon E. Prichard’s 1st Armored Division and advanced against negligible German resistance across the muddy Arno River toward the walled city of Lucca and the ultimate Allied objectives in northwestern Italy, the naval base at La Spezia and the port of Genoa. Then, hampered by torrential autumn rains and relentless enemy shellfire, the 370th Regiment tried but failed to break through the main Gothic Line in the northern Apennine Mountains.

One of the major obstacles to the British Eighth and U.S. Fifth Armies, the heavily fortified Gothic Line stretched 190 miles east to west across Italy from the Ligurian Sea to the Adriatic. After the fall of Rome, Field Marshal Albert Kesselring’s 10th and 14th Armies had retired behind its 2,376 machine-gun nests, 479 gun and mortar positions, and miles of anti-tank ditches. The enemy troops had been ordered to hold the line at all costs.

As the 370th Regiment moved toward the Serchio Valley in northwestern Tuscany, the rest of the 15,000-man 92nd Buffalo Division shipped out to the Mediterranean theater in stages. Elements departed from Hampton Roads, Virginia, on September 22, 1944, and arrived in Italy on October 16. That month and in November, they joined the 370th Regiment in the rugged mountains north of Pisa, facing the western anchor of the Gothic Line. Lieutenant Baker reported, “It was some of the worst country you could fight a war in, but I had grown up in the mountains and knew how to survive in them. From the time I first pulled a trigger at the age of 12, my job was keeping my family going during the Depression by hunting game.”

Besides the harsh weather, terrain, and stubborn enemy, the Buffalo Soldiers had to fight the racism which had plagued them since basic training; they groused that General Almond and his “southern crackers” were using them as “cannon fodder.” Baker said, “We wanted to defend our country, but we faced the most vicious kind of racism, and that soured a lot of the guys. I tried not to let this get to me; I focused on being a soldier and surviving, but sometimes it was hard to tell who the bigger racists were—the Germans in front of us or the commanders behind us.”

In two operations during the harsh winter of 1944-45, the 92nd Division was routed by seasoned German mountain troops. The white commanders blamed the defeats on inexperience and cowardice, an Army report branding the black soldiers as “entirely undependable” and “terrified to fight at night,” and General Clark later called the division the worst in Europe.

All this was denounced by the division’s Lieutenant Frederick Davison, who said the units performed with distinction and that the high number of casualties was due to Almond and his staff. Their orders, said Davison, “were so flawed, so inept, that there was no way that success could have been achieved.”

Rothacker C. Smith, a conscientious objector and medical corpsman who was wounded and captured in one of the battles, agreed that the black soldiers fought bravely. He recalled later, “After the war, I read these reports that the Buffalo men ‘melted away’ in combat, but the men I watched fought with spirit and guts.”

Lieutenant Baker echoed, “There was disharmony in the 92nd, but I had no problems with my platoon when the shooting started…. When I went forward under fire, they followed.”

During their offensive in the fall of 1944, the Allied forces managed to breach the Gothic Line in mid-September, but exploitation proved impossible, and both sides suffered heavy casualties in the protracted fighting. During the lull, the exhausted, mud-covered Allied troops regrouped for a third great push.

When the Christmas season arrived, the Buffalo Soldiers and their comrades celebrated as best they could in their foxholes and in friendly Italian communities. On Christmas Eve, a black platoon delivered a truckload of surplus food, cheese, and chocolate to the village of Barga. “We had never seen so much food,” reported 17-year-old Irma Biondi. “They were wonderful, so nice to us.” The soldiers and villagers shared wine, danced, and sang carols.

But the merriment was short-lived. During the night, the Germans had launched a surprise counterattack—part of an attempt to seize the Tuscany port of Livorno—against the 92nd Division’s positions along the Serchio River. Preceded by an artillery barrage at dawn on Christmas Day, German, Austrian, and Italian Fascist troops advanced, overrunning the Buffalo Division outposts and precipitating a general withdrawal. The invaders penetrated Barga and other neighboring villages, including Bottinaccio and Sommocolonia.

The action was bitter and bloody as the Buffalo Soldiers engaged the enemy swarming through the streets. There was much confusion because some of the invaders were dressed in civilian clothes. Almond’s troops fought desperately and bravely, and a number of Silver Stars were later awarded for heroism. In the village of Sommocolonia, where the enemy sought to roll up the 370th Infantry Regiment’s line, the G.I.s and Germans fought from door to door while the besieged 366th Regiment struggled to drive the invaders away. But the situation deteriorated as black battalions and companies were disorganized and forced to withdraw with heavy casualties.

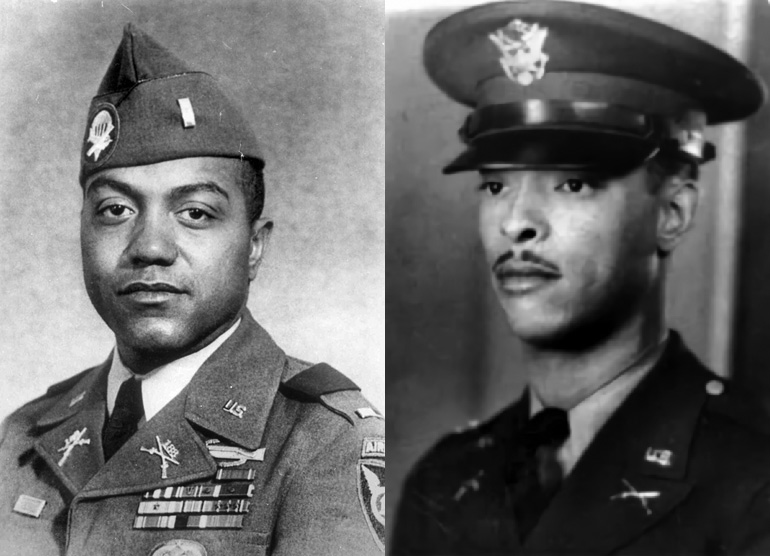

Sommocolonia was the site of one of the most remarkable and tragic feats of heroism in World War II. The hero was 29-year-old Lieutenant John R. Fox, a forward observer with Cannon Company of the Buffalo Division’s 598th Field Artillery Battalion. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on May 18, 1915, John Robert Fox studied biology and science at Wilberforce (Ohio) University, where he participated in the ROTC program and met his future wife, Arlene. They had a daughter, Sandra. Fox was commissioned in 1940 and graduated from the Fort Benning, Georgia, Infantry School in August 1941.

On the night of December 25-26, 1944, Lieutenant Fox was directing defensive artillery fire. When the Americans were forced to withdraw, he volunteered to stay behind with a handful of defenders. He positioned himself on the second floor of a house. When the Germans and Austrians attacked in strength at 8 a.m. on December 26, surrounding the house, Fox radioed for closer gunfire.

The 105mm artillery battery questioned the order and said that the next adjustment would bring salvos directly onto Fox’s position. “Fire it!” he replied. “There’s more of them than there are of us. In three or four minutes they’ll be all over us. Fire directly on the house.” Fox said that the gunfire was the only way to defeat the attackers. The battery opened up again. The house was blasted, and the heroic soldier perished.

When a later counterattack retook the position, Fox’s body was found amid the remains of about 100 enemy troops. A citation said later that Fox “greatly assisted in delaying the enemy advance until other infantry and artillery could reorganize to repel the attack.” He was buried at Colebrook Cemetery in Whitman, Massachusetts.

In a postwar assessment, Lt. Gen. Maximilian Fretter-Pico, a Wehrmacht veteran of the Eastern Front, defended the Buffalo Soldiers’ performance in the fighting around Sommocolonia. He said it was a situation in which good soldiers were poorly assigned. “Your troops were deployed on a front which was too long for the number of men available,” he stated, “and your reserves were too far in the rear, which prevented their being deployed immediately.” While the American press generally criticized the black division, a white officer from another division stated in a letter to The New Republic, “The 92nd didn’t break nearly so badly as white divisions did under similar conditions at the Kasserine Pass.”

A posthumous Distinguished Service Cross was presented to Fox’s widow at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, on May 15, 1982, by Maj. Gen. James F. Hamlett, who had been a 1st lieutenant in the hero’s company. The decoration was eventually upgraded to the Medal of Honor, citing Fox’s “gallant and courageous actions, at the supreme sacrifice of his own life.” Mrs. Fox received the medal from President Bill Clinton at a White House ceremony on January 13, 1997, during which the nation’s highest honor was awarded to six other black veterans of World War II. Lieutenant Baker was the only living recipient.

After the war, the villagers of Sommocolonia erected a monument to Lieutenant Fox and eight Italian soldiers who were killed in the Christmas 1944 artillery barrage. In 2005, the Hasbro toy company introduced a 12-inch action figure of Fox as part of its G.I. Joe Medal of Honor series. Fox’s other decorations were the Combat Infantryman Badge, Purple Heart, and Bronze Star.

He had delayed the enemy advance on December 26, 1944, but only one American officer and 17 enlisted men were able to escape from the village. The Germans pushed back the 92nd Division, which had been holding a 17-mile front across the Serchio Valley. Supported by 4,000 sorties by fighters and bombers, the Allies rushed in reinforcements to plug the hole in their lines and retake the valley. The Buffalo Division was reinforced by two brigades of the British Eighth Army’s 8th Indian Division and two regiments of the U.S. 85th Infantry (Custer) Division. By January 1, 1945, the opposing armies were back at their original positions and the stalemate lingered through the winter.

The Buffalo Division fought on from January to April. Despite more heavy losses and bouts of low morale, its general performance was rated exemplary. A tragic setback on February 6-10, however, shook the black troops. Assigned to a sector south of Viareggio, the 366th Regiment was pinned down for four days by intensive fire from German artillery and coastal guns. A total of 47 officers and 659 enlisted men were killed, wounded, or missing in action.

“The Germans mowed us down like clay pigeons,” reported Sergeant Willard A Williams. He said that his comrades performed “far above and beyond the call of duty.” Yet the 366th was deactivated on March 14 and converted into two general service regiments. Officers and G.I.s wept at the humiliation.

Starting on March 1, 1945, the 92nd Division was thoroughly reorganized, with some regiments withdrawn and others attached. Then, on April 5, it began to attack along the Ligurian coast, spearheaded by its 370th Infantry Regiment and the famed 442nd (“Go for Broke”) Regimental Combat Team. The division, which took more than 11,000 prisoners during April and May, overcame disorganized resistance, captured La Spezia, and reached Genoa on April 27. The Buffalo Soldiers were in the vicinity of Alessandria and Pavin when the German forces in Italy surrendered on May 2, 1945. The division returned to New York on November 26, 1945, and was inactivated at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, two days later.

The Buffalo Division emerged from the European war with a mixed record of reverses and gallant service, and many of its officers and men proudly wore the Distinguished Service Crosses, Silver Stars, Purple Hearts, Combat Infantryman Badges, and Bronze Stars. Its fighting was over, yet it continued to come under fire from committed racists and others.

These views were not shared, however, by three decorated veterans of the Italian campaign who became U.S. senators—Robert Dole of Kansas, Daniel K. Inouye of Hawaii, and Edward W. Brooke of Massachusetts.

Senator Dole, a Republican leader for several years, was wounded while fighting with Maj. Gen. George P. Hays’s crack 10th Mountain Division during the North Apennines and Po Valley campaigns in January-April 1945, and was proud of his association with the 92nd Division. Inouye, who served in the Senate from 1962 until his death in 2012, won the Medal of Honor and 15 other decorations for heroism while serving in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and had “a special, personal memory of the 92nd.” After his right arm was shattered while leading his platoon against three German machine-gun nests on the Gothic Line in April 1945, he received 17 blood transfusions from African-American soldiers. Brooke was the first black elected to the U.S. Senate since Reconstruction and served from 1967 to 1979. A captain in the 92nd Division’s 366th Infantry Regiment who also spied behind the enemy lines in Italy, he lauded his comrades for their fighting spirit and sacrifices.

In the Pacific theater, the 93rd Infantry Division was engaged in defensive missions and port operations in the Treasure islands, New Guinea, and Morotai until the end of the war. After serving in the Philippines, it returned to San Francisco on February 1, 1946, and was inactivated at Camp Stoneman, California, two days later.

The U.S. armed forces were still segregated when World War II ended, but this changed in 1948 when President Harry Truman’s Executive Order 9981 mandated equal treatment and opportunity regardless of race. Beginning in 1951, reverses in the Korean War led to the end of all-black units in the Army and Marine Corps. All of the services integrated the enlisted ranks, though the officer corps remained largely white. The Vietnam War saw the highest proportion of African-Americans ever to serve in an American war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments