By Cole Kingseed

Great commanders need great subordinates. In the campaigns in the Mediterranean and European Theaters of World War II, General Dwight D. Eisenhower was ably served by a number of extraordinary officers, including Mark W. Clark, George S. Patton Jr., and Omar Bradley. Each of Ike’s subordinates contributed mightily to Allied victory, but in the final analysis it was the unheralded Bradley who proved to be Ike’s indispensible lieutenant.

Of the four commanders destined to play a leading role in Europe, Eisenhower was the relative newcomer, but by mid-1942, he had surpassed Clark, Patton, and Bradley in Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall’s estimation. According to historian Martin Blumenson, within six months of Eisenhower’s assumption of command of the European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army, known as ETOUSA, the remaining three settled in as “satellites of Ike.”

Eisenhower and Patton: A Close Friendship

Although six years Eisenhower’s senior at the United States Military Academy, Patton was Eisenhower’s oldest friend. While Patton captured headlines for his frontline leadership in World War I, Eisenhower was confined to Camp Colt, Pennsylvania, where he trained the fledgling tank corps. Following the war, he and Patton crossed paths at Camp Meade in 1919, where the two developed a lasting friendship. At the time, Eisenhower was an untested warrior, while Patton was a legitimate war hero, having received the Distinguished Service Cross for gallantry in action during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. At Meade, Patton commanded the light tanks of the 304th Brigade, while Eisenhower was second in command of the 305th Brigade, composed of newly manufactured Mark VIII Liberty tanks.

It was through Patton that Eisenhower met his mentor, General Fox Conner, who asked for the young Eisenhower to serve as his executive officer in Panama. Patton later bragged that, by sharing his notes with Eisenhower in 1925, Eisenhower graduated number one in his class at Fort Leavenworth the following year. Patton and Eisenhower maintained a lively correspondence between the wars, but much of the original correspondence was lost in transit when Eisenhower shipped to the Philippines in 1935.

On the eve of World War II, Lt. Col. Eisenhower, tired of desk duty, wrote his old friend, soon to be promoted to brigadier general commanding the 2nd Armored Brigade at Fort Benning, Georgia, and requested command of one of Patton’s armored regiments. Patton responded that it seemed highly probable that he [Patton] would be selected for command of one of the next two armored divisions that were being created and that Eisenhower should transfer immediately to the Armored Corps and request assignment with Patton. Patton preferred Ike as his division chief of staff but would support Eisenhower for immediate reassignment if the latter “wanted to take a chance.” Instead of working for Patton, Eisenhower was assigned elsewhere, but their paths crossed briefly in 1941 during the Texas-Louisiana maneuvers of early autumn. One year later, Patton was commanding the Western Task Force that landed at Casablanca during the invasion of North Africa.

Mark Clark: Eisenhower’s Second in Command

Second to Patton in Eisenhower’s esteem before the war was Mark Clark, known to his closest friends as Wayne. Clark was two years Eisenhower’s junior at West Point, but the small size of the corps of cadets allowed familiarity among the classes. Like Patton, Clark was a decorated veteran of the Great War. The two had no contact until 1938 when Eisenhower came to the United States from the Philippines. In October, while en route to his home station, Ike stopped at Fort Lewis, Washington, and saw Clark. The following year, Clark was instrumental in having Eisenhower reassigned to Lewis. Eisenhower reported for duty on New Year’s Day. Two years later, at the conclusion of a series of war games, Clark, now serving on the General Staff, recommended Eisenhower’s assignment to the War Plans Division in the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor. Clark’s and Eisenhower’s careers would be inexorably linked for the remainder of the war.

When Eisenhower arrived in London in June 1942, he was accompanied by Clark, now in command of II Corps and responsible for training the American divisions now arriving in the United Kingdom. When Patton was designated commander of the western invasion force in North Africa in August, Clark reluctantly accepted Eisenhower’s invitation to relinquish command of his corps and to serve as Ike’s second in command in the capacity of Deputy Supreme Allied Commander. In that role, Clark would be the chief planner for Operation Torch.

Omar Bradley: A Spy in Patton’s Headquarters

Bradley, in turn, had the longest relationship with Eisenhower, dating back to their days on the Hudson. Both entered West Point in the summer of 1911, although Bradley was a late arrival. Like Eisenhower, Bradley was a distinguished athlete. While Ike favored football, Bradley excelled in baseball. Both selected infantry as their branch of choice. Prior to graduation, Ike wrote a brief portrait of Bradley in West Point’s yearbook, Howitzer. Ever prescient, even at this early age, Eisenhower opined that Bradley’s most “promising characteristic is ‘getting there,’ and if he keeps up the clip he’s started, some of us will someday be bragging to our grandchildren that, ‘Sure, General Bradley was a classmate of mine.’” Oddly enough, the two future commanders had little, if any, contact in the interwar years.

Their orbits finally came together in the aftermath of the Casablanca Conference of January 1943. By that time, Marshall had already designated Clark as Fifth Army commander on December 1, 1942, a personal blow to Patton, who coveted army-level command himself. Eisenhower had endorsed Marshall’s selection but noted that even though Patton came “the closest to meeting every requirement made of a commander,” Clark would deliver since Fifth Army was temporarily a training command and the “job was one largely of organization and training and in these fields Clark had no superior.”

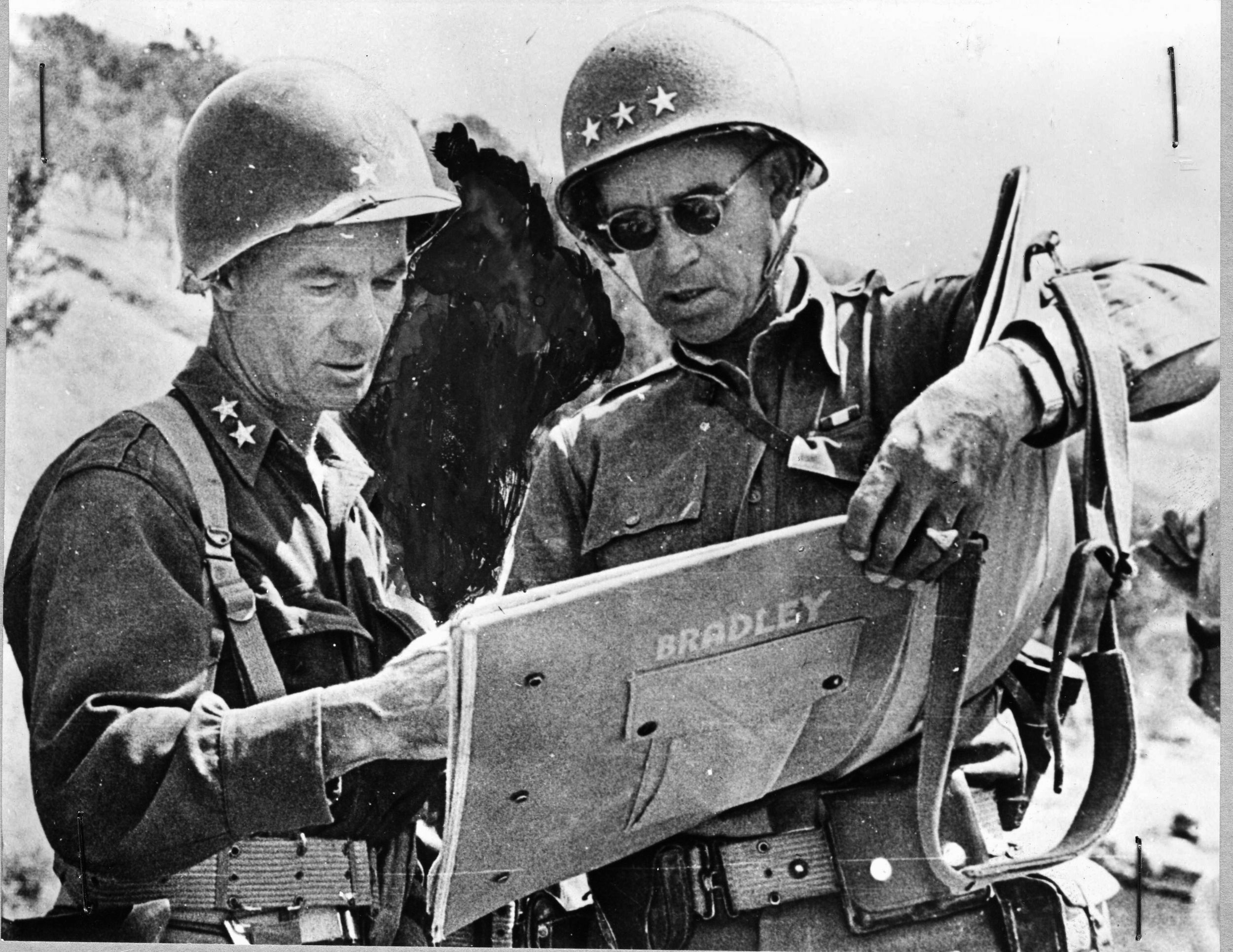

Eisenhower’s problems worsened in February when Field Marshal Erwin Rommel inflicted a devastating defeat on U.S. forces at Kasserine Pass. Relieving the American corps commander, Eisenhower installed Patton in command of II Corps on March 5, 1943. Patton went to work on rehabilitating II Corps and rectifying the operational situation. To assist Eisenhower, General Marshall dispatched Bradley to North Africa to act as Ike’s “eyes and ears.” Ike immediately made Bradley available to Patton for any duty Patton desired. Not content to have “a spy” in his headquarters, Patton made Bradley his deputy commander.

Within weeks, Patton led II Corps to its first significant victory in Tunisia. Now that the first offensive phase was completed, Eisenhower nominated Bradley to command II Corps, while Patton returned to his job of preparing the Western Task Force for the invasion of Sicily, now scheduled for July. On July 10, the date of the amphibious landing, Patton’s command was upgraded to army level, and he assumed command of the Seventh Army. Bradley remained in command of II Corps and slogged it up the middle of Sicily while Patton garnered the headlines with his dash to Palermo, then to Messina. It was a brutal campaign that lasted a month, but the Allied victory restored the prestige of the U.S. Army. At the conclusion of Operation Husky, Ike had three lieutenant generals in theater: Clark, Patton, and Bradley in that order of seniority.

The Rise of Bradley, the Fall of Patton

Sicily marked the emergence of Bradley as Eisenhower’s most valued subordinate. Both Bradley and Patton had performed well, and Ike was quick to compliment each on his respective performance. In the midst of the recent campaign, Eisenhower had instructed war correspondent Ernie Pyle to “go and discover Bradley.” In a number of subsequent dispatches, Pyle characterized the less flamboyant Bradley as “the G.I.’s general,” making “no bones about the fact that he was a tremendous admirer” of the II Corps commander. On the eve of the invasion of France in 1944, Pyle recollected that he had spent three days with Bradley in Sicily and did not “believe he had ever known a person to be so unanimously loved and respected by the men around and under him.”

Bradley’s ascent mirrored Patton’s fall. In August 1943, the publicity surrounding Patton’s slapping of two soldiers in a field hospital severely tarnished his reputation as a field commander. On August 24, Eisenhower praised Patton’s recent conduct of the campaign, noting that “the operations of the Seventh Army in Sicily are going to be classed as a model of swift conquest by future classes in the War College in Leavenworth.” Then came the caveat. “Now in spite of this, George Patton continues to exhibit some of those unfortunate personal traits of which you and I have always known and which during this campaign caused me some most uncomfortable days.”

Recognizing Patton’s future potential, Ike informed Marshall that Patton “possesses qualities that we cannot afford to lose unless he ruins himself.” Patton was, in Ike’s opinion, a preeminent combat commander. Never slowed by caution, fatigue, or doubt, Patton drove his subordinates ruthlessly, and they in turn “turned in magnificent performances in the late show.” Despite this drive, Patton was apt at times “to display exceedingly poor judgment and unjustified temper.”

In spite of these character flaws, Eisenhower remained determined to keep Patton on the team. Two weeks later, Eisenhower backed up his assessment by submitting his list for promotion to permanent major general. Describing Patton, Ike noted that, based on his performance to date, Patton’s leadership of the Seventh Army was “close to the best of our classic examples.” In short, Patton was undoubtedly the “best rounded combat leader in our service.”

In the aftermath of the slapping incidents, however, Ike informed Marshall that under no conditions would he recommend Patton be elevated beyond army-level command. What’s more, Ike assured his chief that “the volatile offensive-minded Patton would always serve under the more even-handed Bradley.”

Mark Clark Takes Command of the Italian Campaign

Writing to Marshall, Eisenhower also addressed Clark’s recent performance. Although Clark had not participated in the conquest of Sicily, he remained the “ablest and most experienced officer we have in planning of amphibious operations…. In preparing the minute details of requisitions, landing craft, training of troops and so on, he has no equal in our Army.” Still, Clark was untested in combat and until he received “battle test in high command,” Eisenhower would suspend final judgment.

Ike’s endorsement of Clark’s potential was a far cry from his ringing endorsement of Clark on the eve of Operation Torch, when Ike had nominated Clark for the Distinguished Service Medal for his role in a secret mission to negotiate Vichy French support during the upcoming invasion. If Clark was destined for a larger role in the war, he would have to prove it on the battlefield, or those commanders who had experienced combat command [Patton and Bradley] would surely eclipse him.

Clark would have his opportunity in September when the Fifth Army invaded the Italian mainland at Salerno. Ike would have the opportunity to observe him there, and nothing indicated that Clark rose to the potential that Ike had anticipated in the early stages of the war. Part of the reason lay in Eisenhower’s subsequent reassignment to command the Allied invasion of France. Despite his close ties to the Mediterranean Theater where he had earned his combat spurs, Ike soon became preoccupied with the greater challenge of planning Operation Overlord.

Bradley in Charge of the Invasion of France

Bradley, on the other hand, was “running absolutely true to form … possessing brains, a fine capacity for leadership, and a thorough understanding of the requirements of battle.” More important, Bradley “has never caused me one moment of worry.” Summing up his assessment of Bradley, Ike stated that although Bradley lacked some of the extraordinary and ruthless driving power that Patton could exert at critical moments, he still had “such force and determination that even in this characteristic, he was among our best…. He is a jewel to have around.” He informed Marshall that he preferred to keep Bradley in theater, at least temporarily, but Eisenhower soon relented.

Putting personal preferences aside, on August 28, Ike gave Bradley a ringing endorsement and strongly recommended Bradley to head the American army designated for the upcoming invasion of France in 1944. “The truth of the matter,” he informed Marshall, “is that you should take Bradley and, moreover, I will make him available on any date you say.” Bradley received his orders on September 3 and left for England on the 8th. Bradley’s selection over his former chief from North Africa and Sicily was a bitter blow to Patton, almost as bad as when he was informed that Clark would receive command of the Fifth Army.

For Patton, the fall of 1943 was a period of terrible uncertainty. “I seem to be third choice,” he lamented in his diary, “but I will end up on top.” Perhaps, but Patton owed his diminished status to his temper and lack of control. Had he not slapped those soldiers, it would have been difficult for Eisenhower not to have named him as chief American planner for Overlord, the invasion of France, now scheduled for spring 1944.

Just how far Patton had fallen was evident in Ike’s secret cable to General Marshall on December 23. Having been named supreme commander for the invasion of Northwest Europe two weeks earlier, Eisenhower expressed his opinion that when army group commanders became necessary in France he profoundly hoped to designate an officer who had had combat experience in this war. His preference for army group commander, when more than one American army was operating in Overlord, was Bradley. One of Bradley’s army commanders should be Patton, Ike opined, as “we should not repeat not lose Patton’s services somewhere as an army commander.”

Clark Falls Out of Favor

As for Clark, he remained far detached from the scene. Even before the Overlord commander had been named, the Mediterranean, and Clark by extension, became a secondary theater in the European war. Clark did not help himself by his inept supervision of the amphibious attack at Salerno. The mismanagement of the exploitation phase led Ike to replace the American corps commander on the scene, Maj. Gen. Ernest J. Dawley, in whom neither Ike nor Clark had confidence. Many observers felt Clark should also have been relieved.

Ike, too, was dissatisfied with his friend Clark, but firing Clark would have been a public relations disaster. And so, Ike compromised, giving Clark nominal support, but informing Marshall that Clark was “not as good as Bradley in winning, almost without effort, the complete confidence of everyone around him, including his British associates.” Nor was Clark “the equal of Patton in his refusal to see anything but victory … but he is carrying his full weight and, so far, has fully justified his selection for his present important post.” It did not take Marshall long to read between the lines.

To make matters worse, Clark lacked the thorough understanding of working with allies, an absolute requirement in Eisenhower’s book. In mid-December, Ike chastised Clark for not informing his superior, British General Harold Alexander, of his recent visit to Sicily. Such an oversight, said Eisenhower, gave the perception of discourtesy to Alexander. These “little points of courtesy must be observed with far greater care in an Allied command than in a purely nationalistic one,” cautioned Ike.

Bradley and Eisenhower’s Invasion Plans

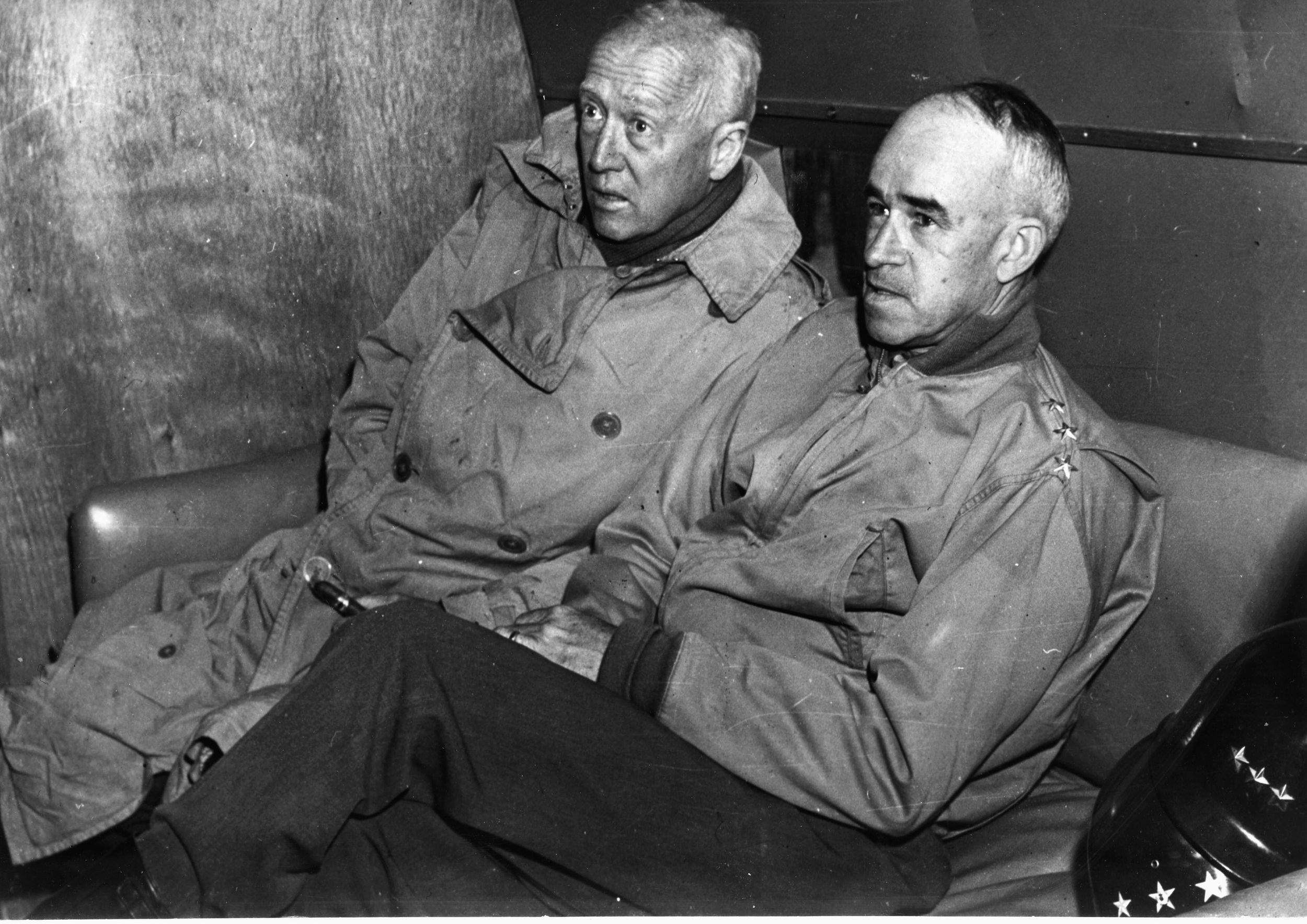

Ike soon followed Bradley to England in January 1944 and immediately assumed his duties as supreme commander. Also arriving later in the month was George Patton, who received command of Third Army. Not destined as the initial assault army, which Bradley was to command, Third Army was designated the follow-up force once the lodgment area reached sufficient size to accommodate two American field armies. At that time, Bradley would be elevated to army group commander.

In mid-February, Eisenhower received his directive from the Combined Chiefs of Staff to “enter the continent of Europe and to undertake operations, in conjunction with the other United Nations, aimed at the heartland of Germany and the destruction of its armed forces.” February through early June marked intense preparations for D-Day. During that period, Ike increasingly depended on Bradley to plan the American portion of the invasion, while Patton was restricted to public appearances in support of Fortitude, the Allied deception plan designed to convince the Germans that Patton would spearhead the real invasion at Calais.

“World War II’s Odd Couple”

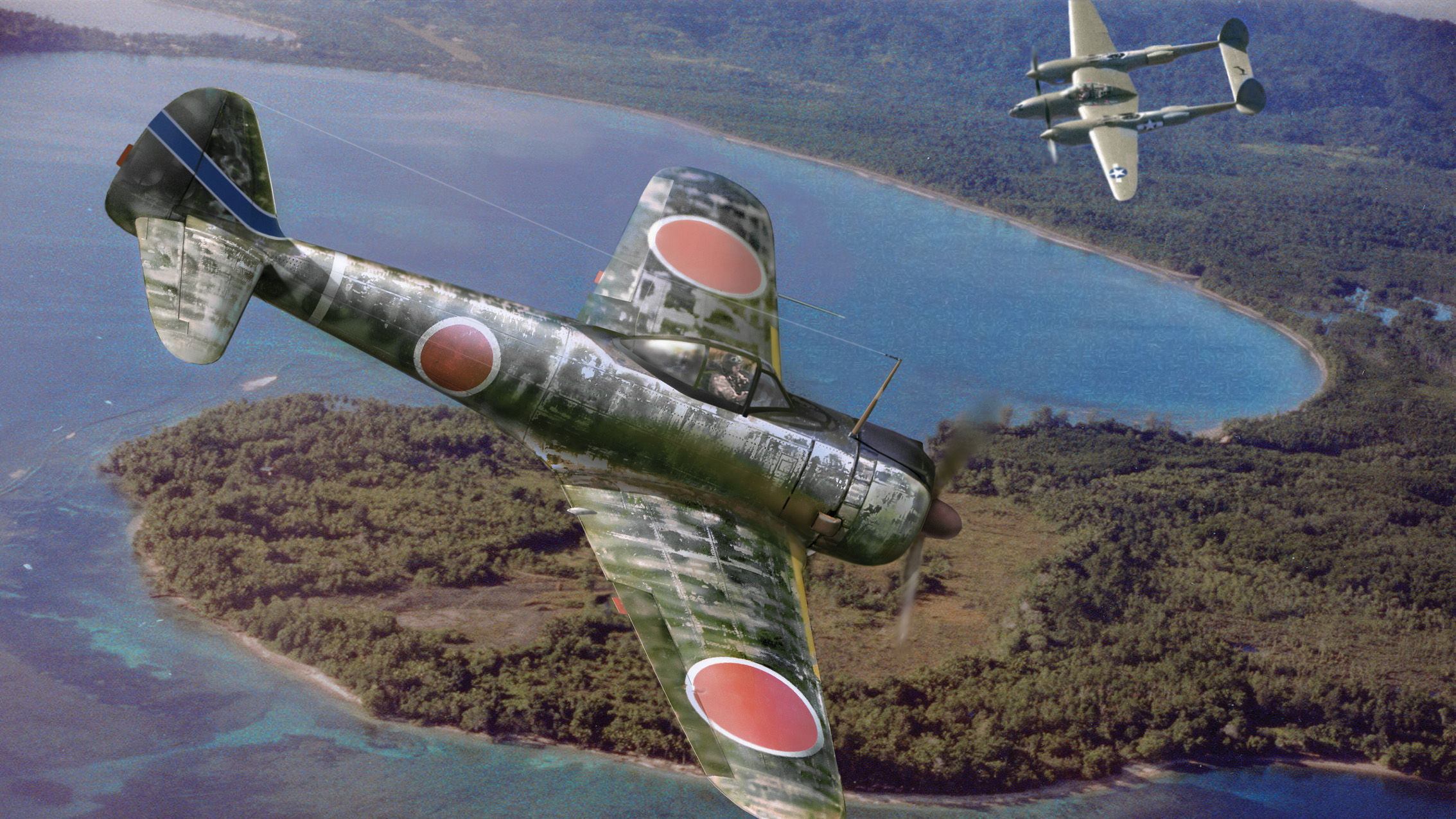

D-Day was one of the most important dates in military history as forces under command of General Eisenhower landed 130,000 soldiers and nearly 15,000 airborne troops. Casualties were excessive, particularly at Omaha Beach, owing in some part to inadequate aerial and naval bombardment. Bradley deserved some of the blame, for he had dismissed several reports from commanders, chiefly Maj. Gen. Charles Corlett, who had amphibious experience in the Pacific. In spite of the setbacks, Ike’s forces were ashore and they meant to stay.

The subsequent battle of the lodgment area and the stalemate in Normandy found Eisenhower frustrated with his principal land subordinates, Bernard Montgomery and Omar Bradley. Ike reserved his harshest criticism for Monty, whose failure to take Caen on D-Day, a highly unrealistic objective, soon led to stalemate on the eastern flank of the invasion area. Bradley, too, was stymied until late July, when his brilliantly conceived Operation Cobra ruptured the German defense at St. Lo and led to the American breakthrough in Normandy. One week later, Ike activated Third Army headquarters in France, and Patton spearheaded the breakout that eventually reached the French capital on August 25.

From Normandy to the German border, Eisenhower had nothing but praise for Bradley and Patton. Bradley, ever cautious but utterly dependable in Ike’s opinion, directed the American portion of Ike’s broad front advance to the German frontier. That campaign contributed to the continued dissolution of his relationship with Patton. Bradley and Patton were never close friends, but both realized that they owed much of their respective success to the other. Historian Blumenson characterized their relationship as “World War II’s Odd Couple.” He was undoubtedly correct, for neither commander liked the other.

Had Bradley had his way, Patton would not have commanded an army in the European Theater. Bradley considered Patton profane, vulgar, too independent, and not a team player. For his part, Patton thought Bradley was overly cautious, indecisive at critical moments, and lacking the resolve to follow through when the operational opportunity presented itself. Moreover, Bradley did his best to publicize the efforts of his other army-level commanders to the detriment of Patton. Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges, who succeeded Bradley in command of First U.S. Army, received the highest praise from Bradley, who always considered Patton not much more than a publicity hound.

The Battle of the Bulge: Patton’s Brilliance, Bradley’s Blunder

By mid-December, the Allied advance approached the Rhine River. The German counteroffensive in the Ardennes on December 16 produced Bradley’s worst moment and Patton’s most brilliant campaign. The massive enemy attack caught Eisenhower’s headquarters by complete surprise. In an effort to coordinate the Allied response, Ike transferred all forces north of the bulge to Montgomery’s command, a move that Bradley interpreted as “the worst possible mistake Ike could have made.” It was the right move on the supreme commander’s part, but Bradley’s feelings were hurt. Fortunately, George Patton’s brilliant turn north relieved the pressure on the southern side of the Bulge and broke the encirclement of Bastogne.

To assuage Bradley’s feeling of demotion, Ike cabled Marshall on December 21 and requested that the chief of staff consider elevating Bradley to four-star rank. Despite internal criticism of Bradley’s delayed reaction to the enemy’s attack, Ike noted that “Bradley has kept his head magnificently and has proceeded methodically and energetically to meet the situation.” Knowing that Marshall had heard of inter-Allied criticism, Ike assured his chief, “In no quarter is there any tendency to place any blame upon Bradley. I retain all my former confidence in him.” Since Congress was not currently in session, Bradley’s promotion was delayed until March 1945.

At the conclusion of the Battle of the Bulge, Eisenhower took stock of the relative merits of each of his American commanders to that point of the war. Confiding in his personal diary, the supreme commander compiled an order of merit for 38 officers based primarily upon his conclusions as to the value of services each officer had rendered in the war and only secondarily upon his opinion as to his qualifications for future usefulness. It was apparent that Ike still valued the services of his three principal subordinates at the beginning of the war.

On the Top of Ike’s List

Even prior to the final push into the heartland of Germany, Eisenhower confirmed that Bradley had eclipsed both Patton and Clark. Bradley’s other army-level commanders ranked farther down the list. Ike rated Bradley first, listing his outstanding characteristics as “quiet, but magnetic leader; able, rounded field commander; determined and resourceful; modest.” Patton appeared fourth on Eisenhower’s order of merit, with his principal qualifications being “dashing fighter, shrewd, courageous.” Next was Clark, as “clever, shrewd, capable; splendid organizer.” The officers whom Bradley sought to advance in Ike’s estimation at Patton’s expense were far distant from the flamboyant Third Army commander.

How much did Eisenhower value Bradley by the end of the war? Following the official deactivation of Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force at midnight, July 13, 1945, Ike penned a rather formal letter of appreciation of their services to all his former principal subordinates in the Allied organization.

To Bradley he wrote, “In my opinion, you are pre-eminent among the Commanders of major battle units in this war. Your leadership, forcefulness, professional capacity, selflessness, high sense of duty and sympathetic understanding of human beings, combine to stamp you as one of America’s great leaders and soldiers.” The former supreme commander signed the message “From your old friend.” No greater tribute could be paid to the “G.I. General.”

Cole Kingseed is a retired United States Army colonel. He resides in New Windsor, New York.

Bradley was not the “G.I. General.” He lived in luxury, played bridge with Ike while others fought the war, and he was jealous of Patton.

Patton was the best general of WWII and IKE’s promotion of the less qualified Bradley and Clark showed Eisenhower was intimidated and jealous of Patton’s success. Bradley’s plan for Normandy and Omaha Beach were disastrous. The Batt5of the Buldge also showed Bradley’s indecision. Patton aggressively moved through France and Belgium defeating the German forces at every turn. IKE’s friendship with Bradley clouded his judgment.

Patton was a very aggressive commander but was not concerned with how many of his own men were wounded or killed as long as he he could get the praise he desired above all else. He might have won the war sooner but a whole lot more Americans would have been buried in Europe. Bradley still would have won the war with or without Patton but he cared about his men more then just vain glory. We have seen recently a self loving vain commander in chief who cared only of his own glory and not at all about the American people or even democracy and how has that turned out? Are we a stronger and better country from his leadership or are we fractured and divided even more then we have been since the Civil War? Great leaders bind the country together and petty ones divided

us.

“Self-loving vain commander in chief who cared only of his own glory and not at all about the American people or even democracy and how has that turned out?” That comment didn’t age so well did it as I write this on 8/29/2021 did it. If you read throughout history and about individuals do not understand that sometimes even the vainest and vulgar of men ironically fulfill Humanity’s most divine purpose. What wisdom do you have to say that only a “Caring and Compassionate person” has the competency to complete life’s most difficult task.

My Father, Royal Budahl served with the Red Bull Division throughout their campaigns in Africa and Europe during WWII. They suffered possibly the worst casualties of any unit in American Forces. Although he too liked and respected General Bradley, he had the strongest admiration and respect for General Clark. I am very proud of my Father’s WWII service as well as all allied military forces. Very gallant men.

You’ve got that backwards. Patton cared very much for his men. He often visited the hospitals to check on his men. Sure he expected a lot out of his men but he knew that fighting harder would, in the end, help save lives. He slept in the field with his men. Bradley being brought up poor loved the lavish life and slept in nice surroundings. Patton was a great commander. Best we had. Should have been a 5 star. But politics had a lot to do with that.