By Christopher Miskimon

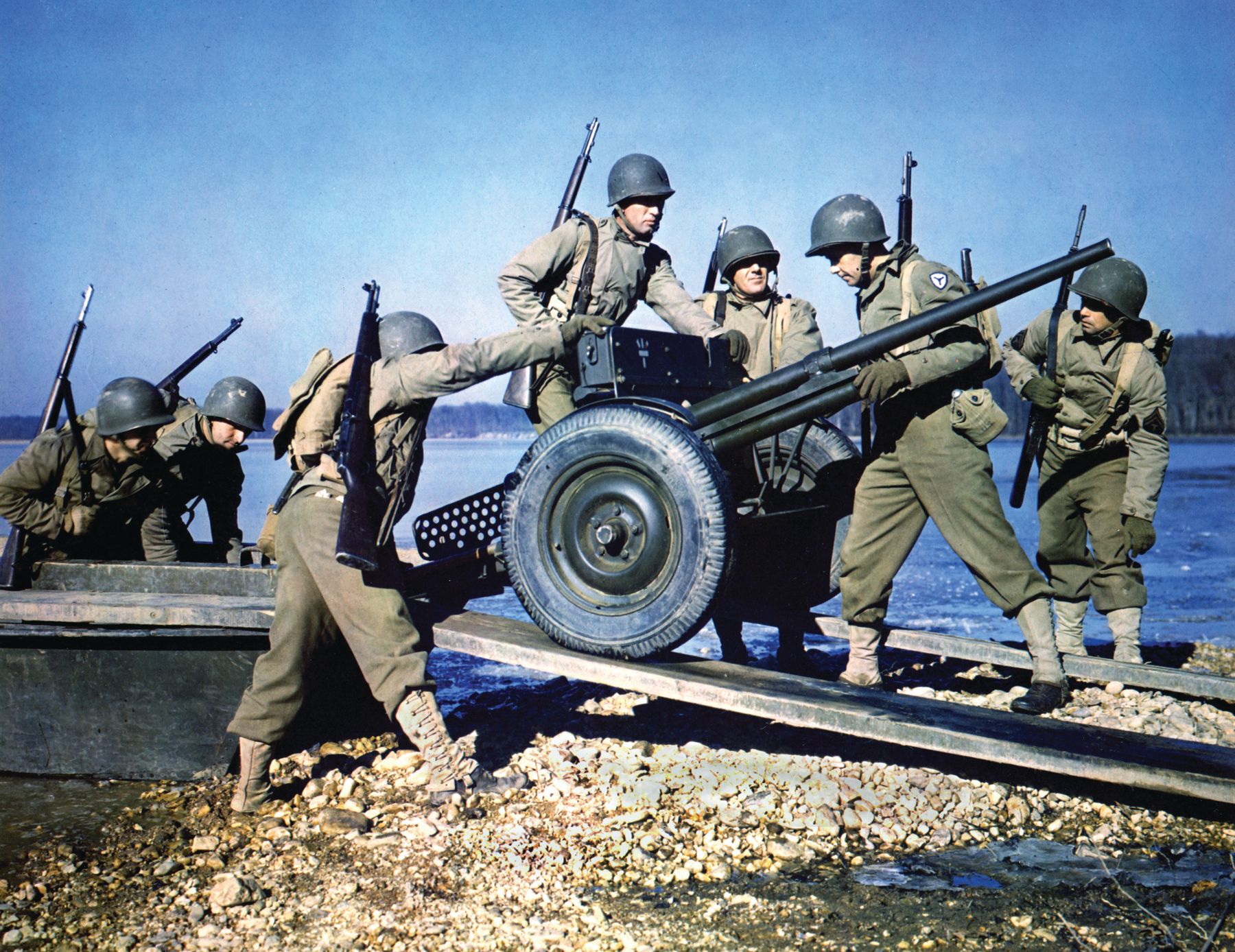

The men of Lieutenant Edwin K. Smith’s antitank platoon, 2nd Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division peered over the gun shields of their 37mm cannon at the column of Vichy French armored cars approaching their roadblock. It was 9 am on November 8, 1942. The platoon had been ordered to man a roadblock near the town of El Ancor, protecting the flank of the 26th Regiment during its landing as part of Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa.

It was a tense moment; Smith’s orders were not to fire unless fired upon. Would these French soldiers fight or not? The question was soon answered when a burst of machine-gun fire stuttered from one of the armored cars. The American return fire was instant. Two of the 37mm guns started banging away, hitting the lead armored car. All three French vehicles fired their own cannon and machine guns at the telltale muzzle flashes of the American guns. Another hit on the leading car set it afire, and moments later a skillful shot from an American 37mm some 1,800 yards away hit the rear armored car, setting it alight and trapping the middle vehicle.

The crews of the burning vehicles abandoned them, taking cover in a drainage ditch. Unable to move, the crew of the middle car did the same. This took the will to fight out of the Vichy troops, who surrendered. The gun crews and their 37mm cannon had just been introduced to combat in North Africa.

The M3 37mm antitank gun was one of the main antitank weapons of the United States in the early years of World War II. It was produced in larger numbers than any other American antitank gun and served through the entire war. This extensive service record comes despite the fact that the 37mm was effectively obsolescent as soon as America entered the war in December 1941.

America’s 18,702 M3s

The cannon’s story begins in the late 1930s as the United States began searching for a more powerful tank-killing weapon. At the time the antitank companies of U.S. infantry regiments were equipped with .50-caliber machine guns, admittedly quite effective against the thinly armored light tanks that were the standard for armored vehicles at the time. Experience gained during the Spanish Civil War forced an evolution in tank design, bringing heavier medium tanks to the forefront. As the United States watched from the sidelines, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, each supporting a different Spanish faction, upgraded their own weapons. The Germans adopted the PAK 36 37mm cannon; this drew increased American interest, and the Army acquired one for testing in early 1937.

In May of that year representatives from the artillery, infantry, and cavalry branches came together at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland to discuss their respective needs for the weapon. The infantry favored a lighter weapon that could be operated by one soldier while the artillerymen favored crew-served cannon. Prototypes were authorized by September 1937, and testing continued through 1938 as the various problems normal to weapons development were overcome.

Several different gun designs and carriages were tested, with the winner being accepted on December 15, 1938, as the M3 37mm cannon mounted on the M4 carriage. It is normal to classify guns and carriages separately as over time a carriage may be used as a platform for more than one type of cannon. When mated together, the complete weapon will generally be referred to by the model number of the gun.

As with many American weapons developed in the sparse fiscal environment of the late 1930s, the M3 did not enter actual production until the end of 1940 as war clouds began to loom and belated preparations were put into motion. Manufacture began slowly, with only 340 guns made in 1940 and 2,252 the year after. America was rearming, but at a snail’s pace. The attack on Pearl Harbor would change that.

With the war against the Axis under way, production was vastly expanded. Quotas were set for all manner of war material. For antitank guns the goal was set at 18,900 weapons by the end of 1943. In actuality, the factories far exceeded this goal. During 1942 and 1943, some 27,343 antitank guns were built with 37mm cannon accounting for 16,110 of this number. Total production of M3s would reach 18,702.

25 Rounds Per Minute

The M3 37mm cannon was a 53.5-caliber weapon, meaning the length of the bore was 53.5 times its diameter. Overall length was 154.5 inches with a width of 63.5 inches and a height of 37.8 inches. It weighed 912 pounds, light enough to be manhandled by its four man crew for short distances. A set of towing straps was provided to make it easier for the soldiers to pull the gun and carriage. The cannon could be traversed 30 degrees to either side of center and could be depressed 10 degrees or elevated up to 15 degrees.

The M3 could fire 25 rounds per minute of a variety of ammunition types. There were two types of armor-piercing rounds. The initial solid steel shot could penetrate 36mm of armor at 500 yards while the improved ballistic-capped round pierced 61mm at the same distance. High explosive and canister rounds were also available. The canister round was for anti-personnel use and functioned like a large shotgun shell, firing 122 3/8-inch steel balls to an effective range of 250 yards.

The new weapon saw use from the beginning of the war. It was issued both as an antitank gun and a tank cannon. The M2 “combat cars” used early in the war—the light M3/M5 Stuart tank series, and the medium M3 Grant/Lee tanks as well as the M8 armored car—all carried 37mm guns, and those 37mm cannon produced as tank guns were augmented by the numbers noted above that were produced for carriage mounts.

For infantry use, the 37mm equipped the antitank platoons of each battalion in an infantry regiment, three guns each. There was also a regimental antitank company with nine guns, for a total of 18 guns per regiment. The Army’s Tank Destroyer Branch made limited use of the 37mm in a self-propelled mounting called the M6. This was a ¾-ton Dodge truck mounting the 37mm on the rear bed. Intended as a stopgap vehicle until dedicated tank destroyer designs could be fielded, a handful of M6s saw service in North Africa in tank destroyer battalions. These units mixed their companies with a platoon of M6s and two platoons of M3 gun motor carriages, a half-track carrying a 75mm weapon.

The M6 had a relatively high silhouette for the diminutive caliber of its gun, and it had no protection for the crew other than a gun shield. It was almost suicidal to use them in modern combat against the Germans, and most company commanders quickly learned to keep their M6s at the rear of their columns. They were replaced at the end of the Tunisian campaign.

The M3’s Baptism of Fire

In its towed version, the 37mm was first used in combat in the Pacific where some were deployed during the Philippine fighting of early 1942. When the Marines went to Guadalcanal, they brought their M3s with them; they proved invaluable against not only Japanese tanks but in breaking up infantry attacks with explosive and canister rounds. At the Battle of the Tenaru River on August 21, 1942, a Japanese force commanded by Colonel Kiyono Ichiki attacked Marines defending along the line of the Ilu River (the Marine’s maps had mislabeled the Ilu as the Tenaru). Just after midnight the Marine pickets heard the approaching Japanese infantry and fell back across the river to warn their comrades. Among the Marine firepower were several 37mm guns that the crews loaded with canister rounds. The Japanese launched their attack with mortar fire and an infantry charge.

The Marines responded, their M3s discharging blasts of steel balls that cut through jungle foliage and human flesh alike. The fighting was hand to hand in some places. After an initial repulse, Ichiki sent in a second attack that bogged down in barbed wire. Small arms and cannon fire poured down on the hapless Japanese, slaughtering them. A Marine counterattack finished the night’s bloody work, leaving nearly 800 Japanese dead. Colonel Ichiki committed suicide.

Two months later, the Americans again used their 37mm guns in action against an attack by the Japanese Sendai Division. Due to a communications error, the Japanese launched their attack a day too soon, hitting the western side of the Marine perimeter. This attack included nine Japanese tanks positioned along a coastal road with infantry behind them, all ready to advance over a sandbar separating the two antagonists.

When the attack began, it was met by the combined fire of U.S. antitank guns, artillery, and small arms. The 37mm cannon barked at the approaching tanks, whose thin armor proved no match for their fire. Only one tank even made it over the sandbar; the rest lay wrecked or burning. The last vehicle, disabled by a Marine who shoved a grenade into its tracks, was picked off shortly afterward. With the armored threat eliminated, the antitank guns shifted their fire to the enemy infantry, leaving some 600 dead on the field at the battle’s end.

Mixed Results in North Africa

After proving itself in the Pacific, U.S. forces next took the 37mm with them to North Africa during Operation Torch. This theater of operations was very different from the Pacific, however. The German Army could field a force of modern tanks along with a well-developed doctrine for their use. The improved models of the German Mark III and IV tanks had thicker armor that the 37mm could only reliably penetrate at close ranges. This fact was not fully appreciated at the time of the landings. The U.S. Army would have to learn through the harsh instruction of battlefield experience.

In the initial phase of Torch, the 37mm performed well enough against the lightly armored vehicles of the Vichy French, but as soon as the Germans were encountered the M3’s inadequacy came to the forefront. Gun crews watched in frustration as their well-aimed shots bounced harmlessly off the armor of attacking panzers. Word went back to the Army Ground Forces (AGF), a stateside command that monitored weapons used in combat to seek improvement. It sent observers to gain first-hand information.

Not surprisingly, the frontline soldiers using the 37mm wanted it replaced quickly, while a number of the observers said the troops were not using the weapon properly. Critics stated the troops expected the gun to work at “excessive ranges” and that it had to be sighted properly to achieve hits on the enemy’s flanks. These critics apparently did not take into consideration that a towed antitank gun unit, once emplaced, cannot dictate the terms of an engagement and must be able to engage an enemy frontally. Guns cannot always be sited where the terrain will be to their advantage.

The prime movers of the 37mm, the jeep or ¾-ton Dodge truck, were unarmored. Bringing them forward under fire to move a gun carried a great risk of losing the vehicle. While these limitations apply to any towed cannon, the M3’s inability to knock out enemy armor only exacerbated the problem.

Criticism of the 37mm continued despite the excuses of some AGF observers, and by mid-1943 the newer 57mm gun was authorized to replace the 37mm on a one-for-one basis. Reequipping took time, so the divisions that went ashore at Sicily in July 1943 were still using many M3s with mixed effect. A high point came during a now famous engagement between U.S. Rangers under Colonel William Darby and an attacking Italian force using captured French Renault R35 tanks. The Italian tanks attacked the Rangers at the town of Gela. Lightly equipped, the Rangers first used bazookas and grenades to resist the enemy assault.

During the fighting, Colonel Darby drove to the beachhead and found a 37mm gun. He towed it back to Gela and set it up, hurriedly chopping open the ammunition box with an axe. Manning the weapon personally, he knocked out one of the R35s and helped fend off the attack. His bravery at Gela resulted in his second award of the Distinguished Service Cross.

Weaknesses of the 37mm Against the Germans

A corresponding low point came when a battalion of the 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, was attacked by the Hermann Göring Panzer Division, which included heavy Tiger tanks. The American 37mm guns were totally ineffective during the attack; the battalion commander was killed while manning one of the guns himself.

Soon afterward, more 57mm guns began arriving, and the 37mm was essentially finished as a dedicated antitank weapon in the European Theater. It continued there only as the primary armament of the M5 light tanks and M8 armored cars. There is a report of an M8 actually knocking out a German Panther tank with a shot from its 37mm. It is believed this would only have been possible by a chance ricochet off the tank’s mantlet down through the thinner roof armor or perhaps a round that landed short, ricocheted off the ground, and bounced up through the belly armor. Such a lucky hit could not be counted on, and units using light tanks or armored cars generally avoided action against German armor.

An Effective Gun in the Pacific

It was a different story in the Pacific, where both the Army and Marine Corps used the 37mm until the war ended. Conditions in the Pacific Theater were more favorable. Much of the fighting occurred in jungle or heavily forested areas that were mostly wild and undeveloped, lacking extensive road networks or built-up areas. Large tracts were wet and marshy with soft ground difficult for vehicles to traverse. The 37mm gun was light enough to be moved by its own crew and manhandled into firing positions. Many of the enemy bunkers and defensive positions were constructed from locally available logs and soil rather than concrete, leaving them vulnerable to the M3’s fire.

The gun was effective against Japanese tanks, which saw no real improvements in armor protection over the course of the conflict. Japanese tanks were thinly armored and vulnerable to the full range of U.S. antitank weapons, including the 37mm gun, though the weapon probably saw much more use in the fire support role. The Japanese did not use very large numbers of tanks and rarely massed their armor, often using what they had in the infantry support role or even dug in as pillboxes.

Rather than engaging Japanese tanks on a regular basis, the 37mm more often used explosive and canister ammunition against infantry or defensive positions. The canister round was found to be very effective at shredding away the foliage that concealed bunkers, revealing their positions for destruction by pinpoint fire. Often, armor-piercing rounds would follow, aimed at the log supports to crack and weaken them. High explosive rounds would finish the job, blowing the bunker apart.

A Small Part of the “Arsenal of Democracy”

During the war the United States gained the moniker of “Arsenal of Democracy” due to its vast exports of weapons and supplies. However, the 37mm played only a very small part in this. The major powers the United States supplied, Great Britain and the Soviet Union, each had adequate supplies of their own light antitank guns, the 2-pounder and 45mm, respectively, and had little need for the comparable American weapon. These nations used 37mm guns as mounted on American armored vehicles supplied via Lend-Lease but did not need them as towed weapons. The vast majority of towed M3s exported went to the Chinese Army; since they were fighting the Japanese, the M3 was a useful addition.

The 37mm had no substantial postwar use outside of a few Third World armies. Today it is relegated to museums and the occasional private collector. Its legacy is that of a weapon obsolete before it entered combat. Nevertheless, it served with both notable success and failure and earned its place in history.

I have a 37 mm casing dated 1941, lot 712-46. Is there a way that I can trace what region it was sent to and if it was used in a battle and stuff like that? Please advise. I’ve just started researching this as of September 2020.

Thanks, Paul