By John Walker

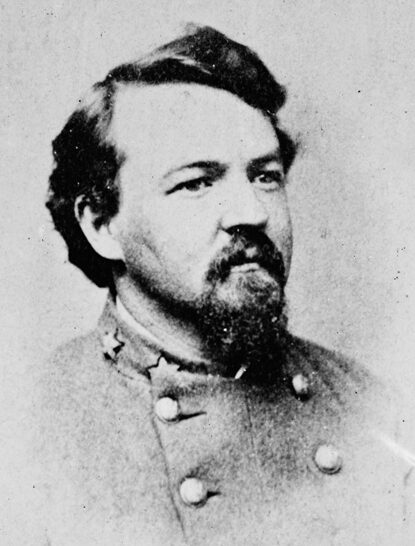

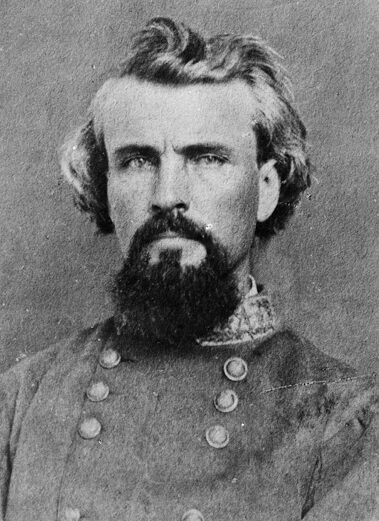

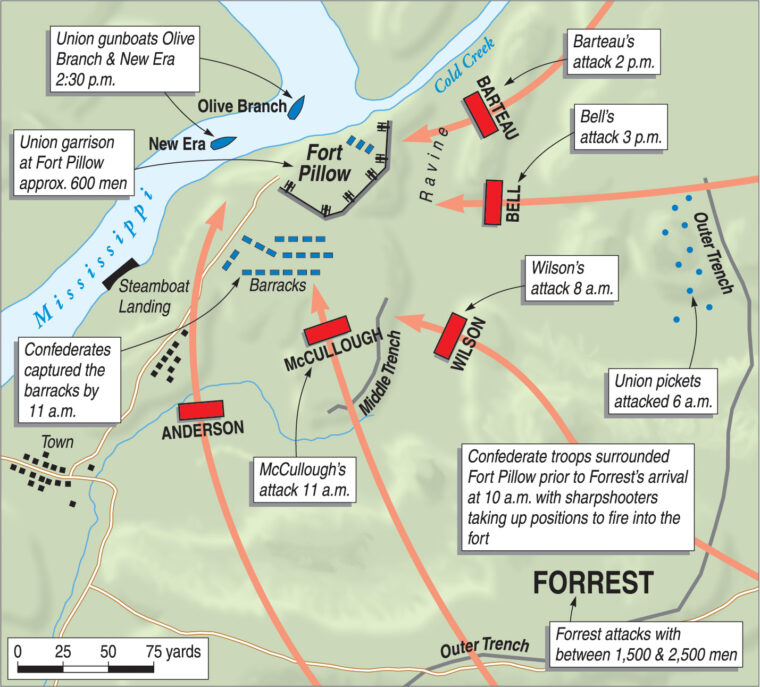

As dawn broke on April 12, 1864, the Union garrison manning Fort Pillow, a small redoubt on a cliff overlooking the Mississippi River in West Tennessee, found itself surrounded by 1,500 Confederate cavalrymen led by Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. Later that afternoon, after Union commander Major William Bradford refused Forrest’s surrender demand, 800 dismounted Confederates stormed the works, quickly overwhelming the fort’s 300 white Southern Unionists and 260 runaway slaves turned artillerymen.

As darkness approached, every member of the garrison was dead, wounded, missing, or captured, and the exhausted Confederates were celebrating their hard-won victory. During the fighting, however, a volatile mixture of pent-up racial animosity, resentment over two years of corrupt and incompetent Union occupation, and reports of depredations committed against local Southern sympathizers by Union soldiers stationed at the fort combined to spark a brief but deadly spasm of vengefulness and reprisal within the attacking Confederate ranks.

As news of the battle spread, Northerners began accusing Forrest and his troops of premeditated slaughter and dubbed the attack “the Fort Pillow massacre,” as it is still widely known to this day. The relatively minor battle sparked a firestorm of anger and recrimination on both sides, North and South, and remains one of the most tragic and contentious incidents in America’s history.

The American Civil War was especially harsh on the once vibrant state of Tennessee, which suffered more than its share of destruction resulting from years of warring armies repeatedly crisscrossing the state. By the time of Fort Pillow, battles had occurred at Shiloh, Murfreesboro, Knoxville, and Chattanooga. Tennessee supplied more soldiers to the Confederacy than any Southern state and also provided more soldiers to the Union Army than any other Southern state. More battles were waged in Tennessee than in any other state save Virginia.

A coalition of 26 East Tennessee counties tried twice to secede from the state itself after Tennessee became the last state to join the Confederacy (after President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 troops from each state to put down the rebellion, Middle Tennessee in a June 1861 referendum voted overwhelmingly to secede from the Union, tipping the balance in favor of West Tennessee). The state legislature in Nashville denied their request and sent Confederate troops under Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer to occupy the region. Many East Tennesseans subsequently engaged in guerrilla warfare against state authorities, burning bridges, cutting telegraph wires, and spying for the Union.

The nation’s vice president, Andrew Johnson, was a Tennessee Union loyalist. Strong pro-Union sentiment existed for the duration of the war and stymied the efforts of Confederate commanders—General Edmund Kirby Smith, Maj. Gen. Sam Jones, and Zollicoffer—to control the region. They oscillated between harsh measures and conciliatory gestures to gain support but had little success, whether they arrested hundreds of Unionist leaders or allowed men to escape Confederate conscription. Union forces finally captured Middle and East Tennessee in 1863.

Governor Isham Harris, conversely, was a staunch Confederate, as were three other prominent Tennesseans, Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham, and Forrest. Harris fervently believed in popular sovereignty—each state should decide the slavery question for itself—and questioned why all new United States territories became solely non-slave, which could potentially upset the fragile free state-slave state balance. Southerners, correctly claiming they had supplied more soldiers for the Mexican War than did the Free States and territories combined (the South was the fiercest supporter of the war as well), feared the loss of territories they had won in that war.

Built on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River by Confederates in mid-1861 and named for the commander of their forces in Tennessee at that time, Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow, Fort Pillow became untenable after the fall of Fort Donelson, Fort Henry, Island No. 10, and the Union occupation of Memphis, Tennessee. Union forces intermittently occupied the fort after the Confederates abandoned it on June 5, 1862. In January 1864, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman ordered the fort evacuated and all available troops sent to support his Meridian, Mississippi, expedition.

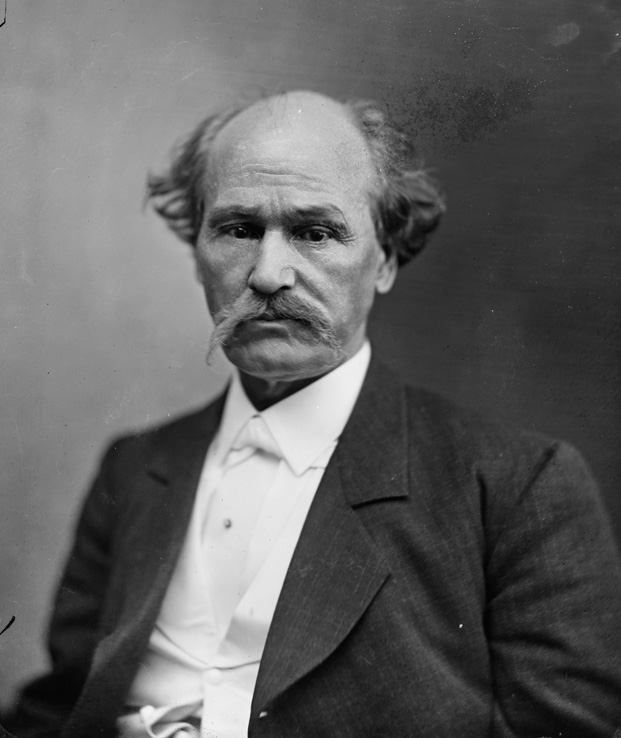

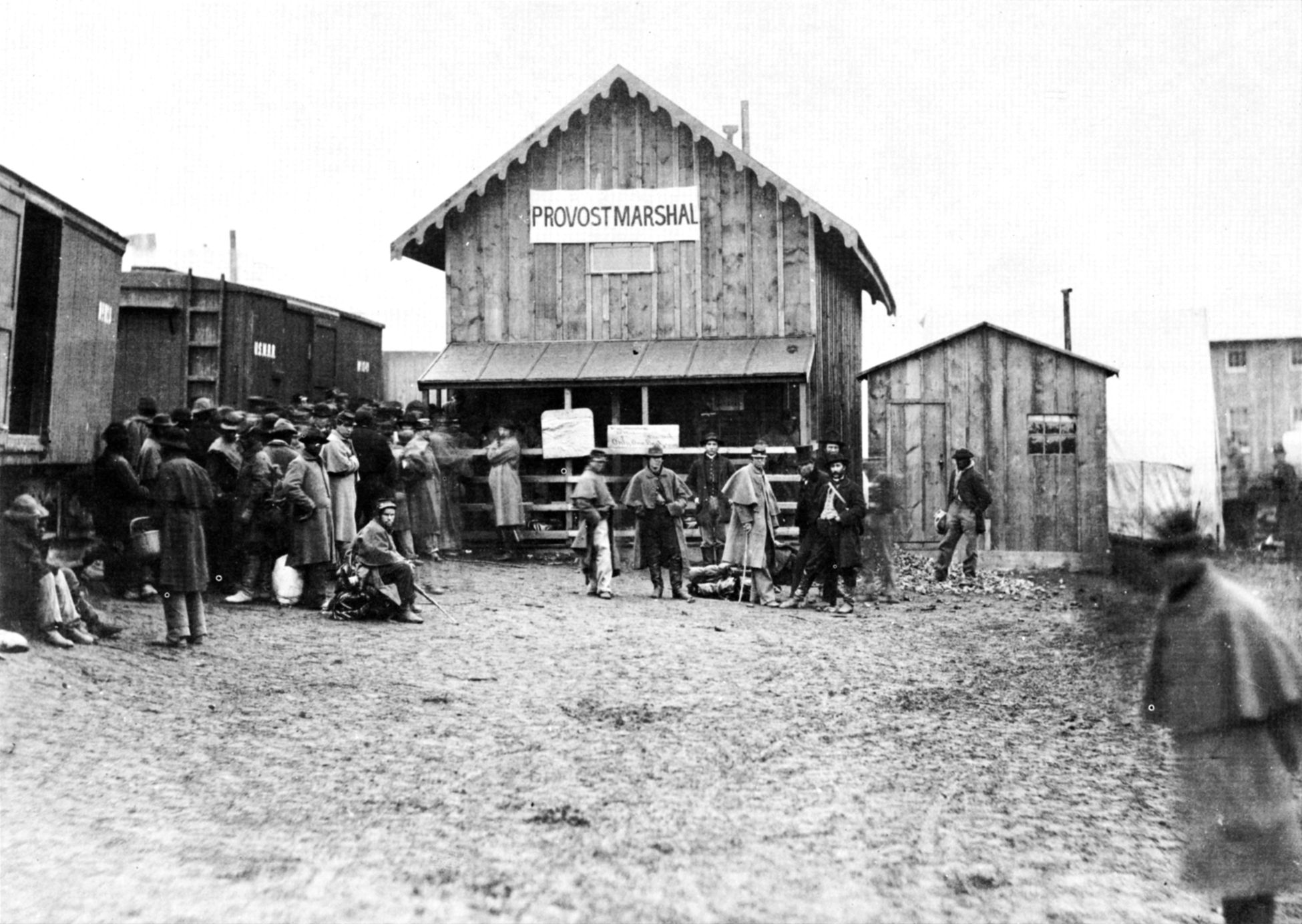

Major General Stephen Hurlbut, commander of the U.S. XVI Corps headquartered in the city of Memphis 40 miles south of the fort, issued orders dated January 11, 1864: “The regiments at Fort Pillow will be sent forward to Memphis and that post abandoned. He [the fort’s commanding officer] will also send forward to Memphis the two best of his three batteries of light artillery. All public property at Fort Pillow to be sent to Cairo or Memphis.”

However, Fort Pillow was situated in rich Tennessee bottomland. The location not only was ideally located for river trade, but also for growing bumper crops of cotton and corn. It was not unheard of for Union commanders to involve themselves in illegal trade in occupied areas. A garrison often might remain in an occupied area for one or more years, making it profitable to engage in farming.

In February, Hurlbut, whose service record already included numerous allegations of continual drunkenness, inability to command, and shady financial dealings in occupied areas, began reoccupying the abandoned fort without Sherman’s knowledge. Fort Pillow, close to Memphis and out of the limelight, was perfect for shady dealings. Hurlbut first sent Major Lionel F. Booth and four companies of heavy artillery, the 1st Battalion, 6th U.S. Heavy Artillery (Colored), or 6/USHAC, and a section of one company of light artillery, D Company, 2nd U.S. Light Artillery (Colored), or D/2/USLAC, to the fort, a move that was completed by March. The majority of Major Booth’s artillerymen were runaway slaves from Tennessee and Mississippi.

During the same period, Bradford, who had been recruiting Tennessee Unionists and Confederate deserters in Paducah, Kentucky, and Union City, Tennessee, shifted his base of operations to Fort Pillow as well. Bradford, a Tennessee loyalist, attorney, and abolitionist from Forrest’s home county of Bedford, was especially scorned by Southern supporters in the area; prior to receiving a commission in the U.S. Army, he had led a band of pro-Northern guerrillas in raids against Confederate sympathizers in Middle and West Tennessee.

Forrest’s first biographers wrote of this episode, “Under the pretext of scouring the country for arms and rebel soldiers, Bradford traversed the surrounding country with detachments, robbing the people of their horses, mules, beef cattle, beds, plates, wearing apparel, money, and every possible movable article of value.”

The biographers colorfully elaborated, “All this was besides venting upon the wives and daughters of Southern soldiers the most opprobrious and obscene epithets, with more than one extreme outrage upon the persons of these victims of their hate and lust.” Bradford’s unit, the 295-man 13th Tennessee Cavalry (U.S.) included at least 67 known Confederate deserters (derided as “homegrown Yankees” and “Tennessee Tories”) by the locals. About 100 civilians—family members, workers, and cotton traders—also were inside the fort, but all but 10 male civilians were evacuated before the battle. By March 1864, Fort Pillow was garrisoned once more, by almost 600 Union soldiers, a Union-raised force serving in a Southern state.

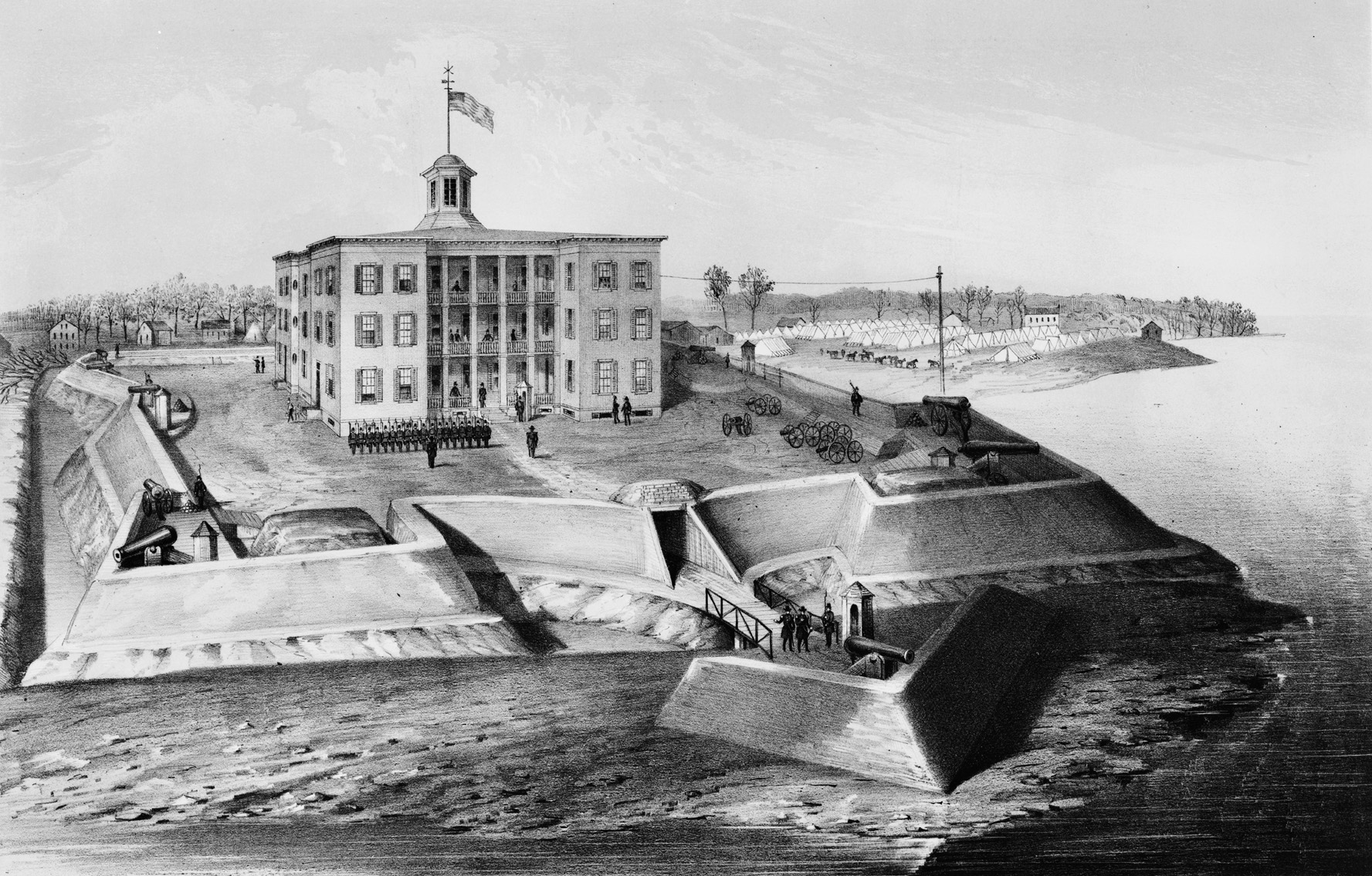

Fort Pillow originally was built with three distinct sets of defensive works, its outer ring shaped in a rough semicircle. Booth’s entire command did not exceed 600 effectives and boasted only six field pieces, so he chose to use only a portion of the fort. He selected a 30-acre promontory at the northernmost end of the second line of the old Confederate works, on a bluff that was surrounded on all sides by a deep ravine.

Within this area, Booth constructed an earthen redan in the shape of an elongated letter W, which enclosed an area of one acre fairly close to the bluff. The tops of the W faced west toward the river, the bottoms east toward Forrest’s forces. The fort’s six cannon were placed within the redan. Outside the redan, the Federals dug rifle pits along the inner edges of the ravine. Booth allowed the construction of several outbuildings just outside the works, including a hospital, dry goods store, quartermasters’ offices, and a line of four flimsy wooden barracks on the southern (right) flank of the Federal defenses.

Tactically, the location of the redan chosen by Booth was a poor one since the hill he selected was lower than a number of hills to its north and east, which provided an attacking force with excellent fields of fire. This could have been simply a case of bad judgment on Booth’s part, but it was the culmination of crucial judgments that made his actions suspect. The fortified area measured only about 100 yards by 100 yards. For Union garrison members who sought refuge within the confines of the redan during the battle, hemmed in like sardines, the only chance to gain safety and cover was to press up against the inside face of the redan. This congestion hampered the loading and firing of weapons.

Furthermore, the fort’s artillery pieces could not be depressed sufficiently to be effective against an attacking force that had closed on the works. Although Booth had reached an agreement with the Union Navy to patrol the river side of the fort, the gunboats’ high angle of fire was unsuited to a battle at close quarters. If Booth truly anticipated having to defend Fort Pillow, he seems to have given every advantage to his attackers.

By spring 1864, much of Tennessee was desolate, picked over and brown, with burned farmhouses and barns dotting the landscape. While Forrest and his 3,000 men camped at Jackson, Tennessee, preparing to move into Kentucky to gather horses, supplies, recruits, and deserters, he was angered by tales he began hearing from local residents. One Jackson woman whose property had been looted by Union raiders—members of the 6th Tennessee Cavalry (U.S.) under Colonel Fielding Hurst—had earlier taken Hurst to court and won a judgment of over $5,000 against him, after which Hurst and his men successfully extorted the same amount from the citizens of Jackson in return for not burning the city to the ground.

“The whole of West Tennessee is overrun by bands and squads of robbers, horse thieves, and deserters, whose depredations and unlawful appropriations of private property are rapidly and effectually depleting the country,” Forrest wrote angrily to his superior, Polk. Jackson residents also warned Forrest about the “nest of outlaws” manning Fort Pillow.

Forrest, accompanied by fugitive Tennessee governor Isham Harris, promised the people of Jackson he would “attend to” the Unionists at Fort Pillow in a couple of days. In the meantime, on March 22 he issued a proclamation “to who it may concern” that because of alleged crimes and Federal refusal of Confederate demands for redress, he was declaring “Fielding Hurst, and the officers and men of his command, outlaws, and not entitled to be treated as prisoners of war should they fall into the hands of the forces of the Confederate States.” Instead, they would be shot down whenever and wherever they were encountered. This was partly bluster on Forrest’s part, but Union authorities took the threat seriously enough to warn Hurst “against allowing your men to straggle or pillage … as a deviation from this rule may prove fatal to yourself and your command.” On May 1, 1863, the Confederate Congress enacted an official policy that called for the return of captured slaves to their owners and the summary execution of white officers commanding black Union units. It was in this toxic atmosphere that Forrest and his troops rode north toward Kentucky in late March.

Forrest detached part of his column, 500 troopers under Colonel William Duckworth, to capture Union City, a crossroads village in northwestern Tennessee. Duckworth carried out his assignment with finesse, posing as Forrest and sending a strongly worded surrender demand to the Union garrison’s commander, Colonel Isaac Hawkins, who had already surrendered to Forrest once before. Hawkins demanded to see Forrest in person before capitulating. Duckworth responded [as Forrest], “I am not in the habit of meeting officers inferior to myself in rank … but I will send Colonel Duckworth, who is your equal in rank, and who is authorized to arrange terms and conditions.” The ruse worked, and Hawkins, though holding a strong position, surrendered himself and his 500 soldiers along with 300 horses and $60,000 in U.S. currency the garrison had recently received in pay.

Forrest attacked Paducah, Kentucky, the next day and drove the Union commander, Colonel Stephen Hicks, and his men into Fort Anderson along the Ohio River west of town. After several hours of exchanging fire, during which black artillerists inside the fort inflicted considerable casualties upon Forrest’s men, Forrest sent his usual surrender demand, which Hicks refused. He had a force of 700 men, heavy artillery, and two gunboats close by in support. As it happened, Forrest’s objective was to pin the Union garrison inside the fort while his own troops pillaged Union stores within the city, and he withdrew from Paducah on the night of March 25 with 400 horses, 50 prisoners, and a large supply of clothing, saddles, ammunition, and medical supplies.

Safely back in Tennessee, Forrest turned his attention to Fort Pillow, an inviting target, but the Confederates first dealt with Colonel Hurst and his command. Confederate Colonel J.J. Neely and his troops picked up Hurst’s trail between Somerville and Bolivar, Tennessee, and on March 29, in Brig. Gen. James Chalmers’s words, “met the traitor Hurst at Bolivar, after a short conflict, in which we killed and captured 75 of the enemy, drove Hurst hatless into Memphis, and captured all his wagons, ambulances, and papers, as well as his mistresses, both white and black.” In conjunction with his plan to take Fort Pillow, Forrest sent units to demonstrate against Memphis and Paducah as diversions and as opportunities to scour the area for additional horses and supplies.

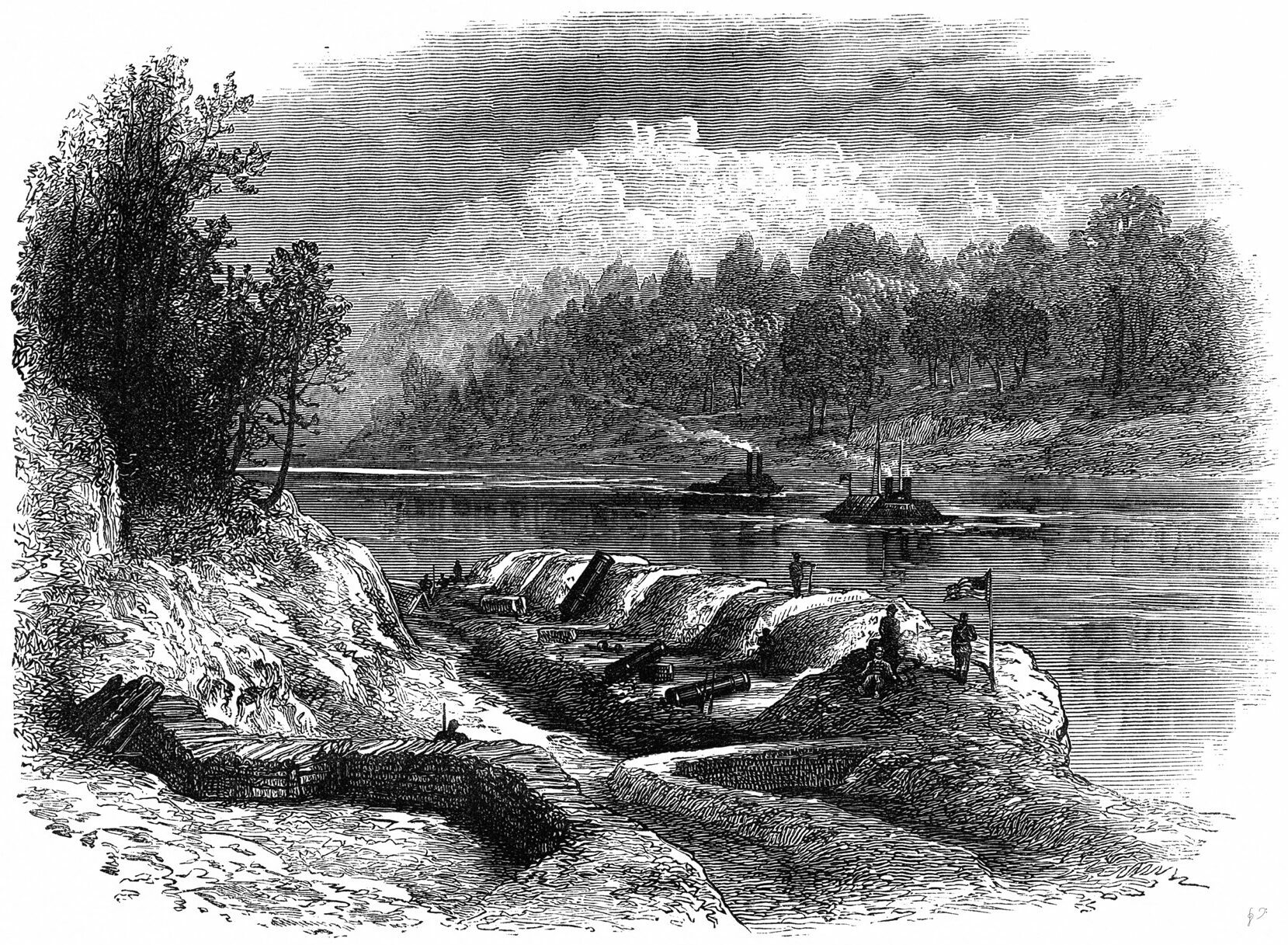

By May 1864, the Union enjoyed complete control of the Mississippi River. A typical day’s river commerce might see as many as five steamers laden with cargo pass by Fort Pillow bound for Cairo, Illinois. The U.S. Navy was represented by the gunboat USS New Era under the command of Captain David Marshall. New Era’s port of call was Fort Pillow, and it was part of the fleet commanded by Admiral David Dixon Porter to patrol this part of the river. The steamer USS Silver Cloud, commanded by Master William Ferguson, USN, was close by, its port of call being Island No. 10.

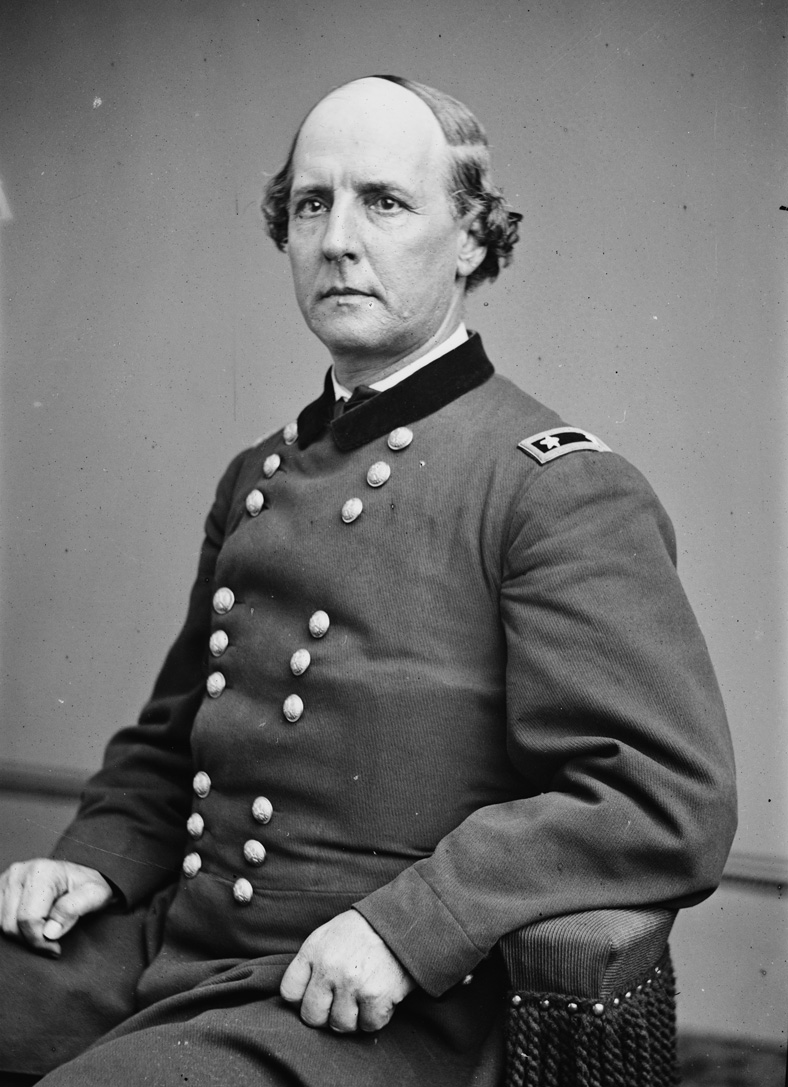

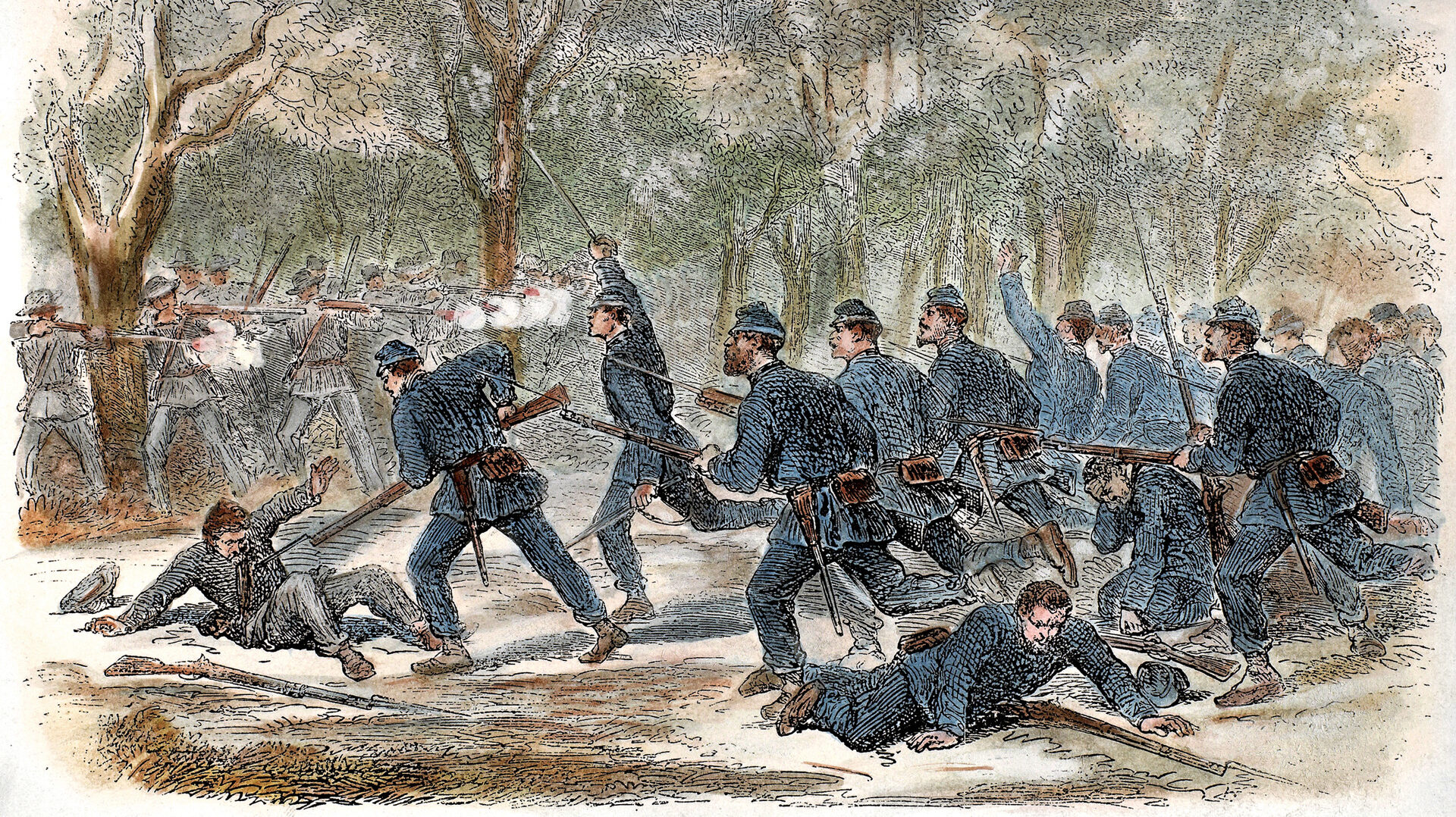

Early on April 12, 1864, about 1,500 Confederate troops commanded by Brig. Gen. James Chalmers, one brigade from each of Forrest’s two divisions, converged on Fort Pillow. Booth’s reconstituted defenses now extended in a 125-yard semicircle behind which the land rapidly fell away to the river. Deep ravines crisscrossed the landscape east of the fort, and the only really open, flat terrace of land lay to the southwest where the four barracks had been built. The open side of the redan overlooked the river from a steep, vine-choked bluff with a drop of 80 feet. A narrow, two-foot-wide footpath ran along the face of the bluff down to the river’s edge. The Confederates quickly drove in the outlying Union pickets and occupied hillocks that allowed Confederate sharpshooters to begin engaging the fort’s defenders. Booth attempted to burn the cabins and outbuildings located outside the ravine, including the wooden barracks, to prevent the attackers from using them for cover and concealment. During the attempt, a number of Union defenders were shot down and inadvertently burned in the very buildings they were torching to prevent Confederate use.

Directed by Forrest to invest the position and await his arrival, Chalmers followed his orders to the letter, advancing slowly and cautiously but steadily driving the defenders back into their innermost earthwork, after which the Confederates closed on the Union works. At 9 am, after a Confederate sharpshooter killed Booth, Bradford assumed command. Having ridden for the better part of a day and a night, Forrest arrived at mid-morning to find the fort virtually surrounded.

As was his norm, Forrest carefully reconnoitered the field, acquainting himself with the lay of the land and the enemy’s positions. During this early reconnaissance, Forrest’s horse was struck by Union gunfire; the horse reared and fell, badly bruising Forrest in the process. Forrest would lose two more horses before the day was over, shot from beneath him. While Forrest began making troop dispositions to conduct a double envelopment as well as a frontal attack, New Era began firing at the nearby Coal Creek ravine north of the fort in an unsuccessful attempt to keep the Confederates from reaching the area. At 1 pm, New Era pulled away upriver to allow its guns to cool, having fired almost 300 shells with little effect.

Forrest asked one of his cavalry brigade commanders, Colonel “Black Bob” McCulloch, what he “thought of capturing the barracks and houses which were near the fort and between it and my position.” McCulloch told Forrest that he could silence the enemy’s artillery by taking those positions, and Forrest unhesitatingly ordered him to go ahead.

The Federals had succeeded in burning only the row of barracks nearest the fort before heavy Confederate fire drove them back, and now enemy sharpshooters kept the Federals pinned down while McCulloch’s men, obscured by smoke from the one torched barracks, slipped in among the remaining three, just 60 yards from the southwest slope. A Union survivor, Lieutenant Mack Leaming, later recalled, “From these barracks the enemy kept up a murderous fire on our men, despite all our efforts to dislodge them.”

At 3 pm, Confederate ammunition resupplies arrived. After his troops successfully seized the rifle pits east of the fort, driving the last group of Federals into the redan, Forrest knew he was in a good position to storm the fort but preferred to send in a surrender request, as was his custom. Unaware that Booth had succumbed to his wounds, Forrest sent in his demand under a flag of truce. It read, “The conduct of the officers and men garrisoning Fort Pillow has been such as to entitle them to being treated as prisoners of war. I now demand the unconditional surrender of your forces, at the same time assuring you that you will be treated as prisoners of war.”

Explaining that his men had just received a fresh supply of ammunition, Forrest continued, “From their present position, they could easily assault and capture the fort. Should my demand be refused, I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command.” This last threat was a ploy, part of Forrest’s much used and often successful psychological arsenal by which he hoped to encourage his enemy, here and elsewhere, to give up without further struggle.

Union gunboats, now including USS Olive Branch and the steamer USS Liberty, began steaming in the direction of the fort in what appeared to the Confederates to be an attempt to reinforce it. Forrest responded by moving troops—200 men each under Captain Charles Anderson and Colonel Clark Barteau—toward the Mississippi River on both sides of the fort to repulse any Union landing attempts. Liberty, carrying hundreds of Federal infantrymen, picked up a number of refugees from a sandbar near the landing, then moved off after taking fire from Confederate sharpshooters. The Union later claimed Forrest had violated the rules of warfare by moving troops while under a flag of truce, without mentioning the actions of its own gunboats.

Olive Branch, carrying two batteries of artillery and 120 Federal soldiers, got no signals from the fort and passed by, eventually docking at Cairo, Illinois. Meanwhile, Bradford responded to Forrest’s note by requesting, in Booth’s name, one hour in which to consult with his officers and those of the New Era. Union soldiers along the ramparts, both black and white, seemingly agreeing with their new commander’s recent boast that the fort could not be taken, now began gleefully and profanely heckling the attacking Confederates, which only served to further enflame passions on the Confederate side. In a questionable move, Bradford allowed barrels of whisky, with dippers for the defenders to drink from, to be placed on the ramparts.

Convinced his adversary was stalling, Forrest quickly replied in writing that he would allow just 20 minutes for a decision. Growing impatient, Forrest rode to the scene of the negotiations between the truce parties; when he arrived, he found they were arguing over whether he was actually on the field. After convincing the Federals that he was indeed Bedford Forrest, the general stated that he wanted to know from Booth “in plain and unmistakable English, will he fight or surrender?”

The Union party returned to the fort, got an answer, and rode back. Forrest took the note, unfolded it, and quietly read the succinct reply, “I will not surrender.” He saluted and went back to his command post 400 yards from the fort fully determined to carry the works by assault and began issuing orders to that effect. The “Wizard of the Saddle” remained at his command post and didn’t lead the charge as he usually did due to his earlier painful injuries.

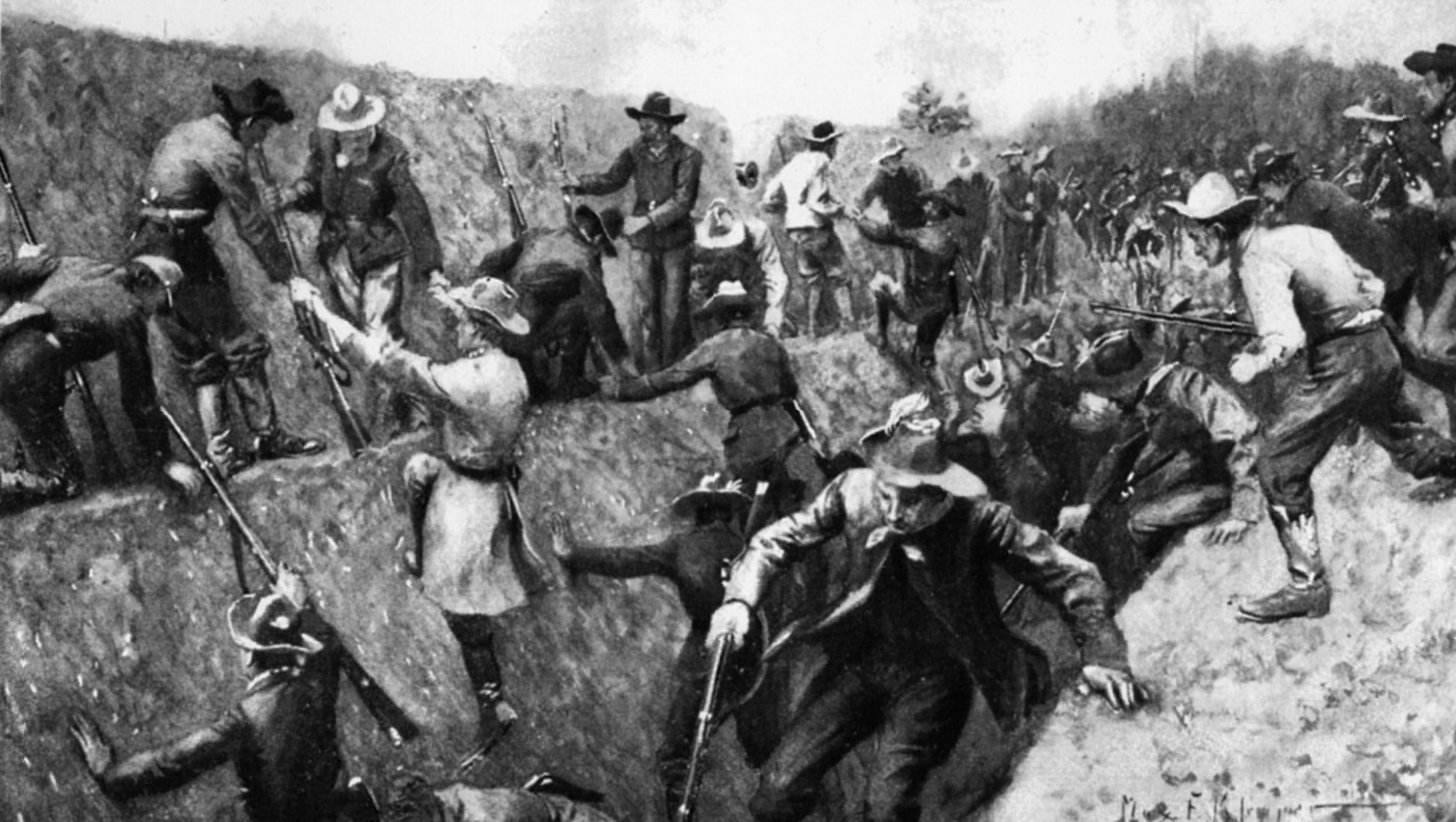

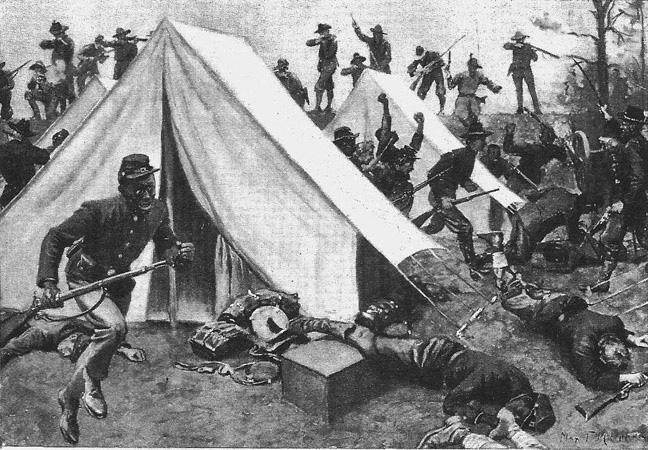

At 5 pm, Forrest ordered his bugler to sound the charge, and 800 Confederates surged forward. While Confederate sharpshooters kept the defenders’ heads down, the first wave of attackers plunged into the ditch and then helped the second wave gain the ledge between the ditch and parapet. The Confederates in one long wave climbed to the crest of the parapet, leaped over the wall, and began blazing away at the surprised Federals with carbines, double-barreled shotguns, and six-shot revolvers.

Meanwhile, three more waves of attackers rushed forward, Bell’s troops breaking through in the center, Barteau’s 22nd Tennessee from the north, and McCulloch’s brigade from the south. A black artilleryman, Private John Kennedy of A/2 USLAC, heard Bradford shout, “Boys, save yourselves!” The young artilleryman and others urged Bradford to “let us fight yet,” but the major, seeing Confederates pouring in from all directions, said despairingly, “It is of no use anymore!” and headed for the rear.

Any thought of an orderly withdrawal after first lowering the fort’s flag to signal the garrison had surrendered was abandoned, and the retreat became a panic-stricken rout. That the flag continued to fly is significant. Had Bradford or one of his soldiers lowered the flag—the universally accepted 19th-century signal during combat that a garrison had surrendered, and therefore an unmistakable signal to the victorious attackers to stop firing—some of the carnage might have been avoided.

Confusion reigned within the fort; some defenders dropped their weapons and attempted to surrender, some continued loading and firing their weapons, others simply broke and ran, spilling over the bluff’s brow and sliding down the treacherous, vine-choked bank toward the river.

One Confederate officer and Tennessean, DeWitt Clinton Fort, was in the forefront of the attack. “The wildest confusion prevailed among those who had run down the bluff,” wrote Fort in his diary. “Many of them had thrown down their arms while running and seemed desirous to surrender while many others had carried their guns with them and were loading and firing back up the bluff at us with a desperation which seemed worse than senseless. We could only stand there and fire until the last man of them was ready to surrender.”

Booth and Marshall had worked out a prearranged signal for New Era to steam close to the bank at the first sign of trouble and “give the Rebels canister.” Instead, no doubt to Bradford’s horror, Marshall swung the gunboat away from the shore, its ports closed tight, while Confederate sharpshooters stationed above and below the fort poured in a deadly enfilade fire. In front of a Congressional committee that investigated the Fort Pillow battle, Marshall said, “Major Bradford signaled to me that we were whipped. We had agreed on a signal that if they had to leave the fort, they could drop down under the bank, and I was to give the Rebels canister.”

Unfortunately for the defenders, both sides had now become so intermingled that fire from New Era would have killed friend and foe alike. Marshall went on to say that he had abandoned the plan partly because he was afraid the Confederates might “hail in a steamboat from below, capture her, put on four or five hundred men, and come after me.”

According to the ship’s log, New Era fired at least 260 shells at the Confederates during the battle’s earlier stages, but then “the fort’s flag came down and an indiscriminate massacre was commenced on our Troops, the enemy firing volley after volley into them while [they were] unable to resist, at the same time turning their fire on us. The enemy being in overwhelming force, we proceeded up the river.”

In the days after the battle, one of Forrest’s comments, “The river was dyed with the blood of the slaughtered for 200 yards,” was considered by many Northerners proof that a massacre had taken place. However, the soldiers that were killed in the river were retreating, hoping to reach safety upriver. There is no prohibition in international law against killing retreating enemies, who if allowed to escape might regroup in strength and return to the conflict.

There are many contradictory accounts by soldiers on both sides regarding what took place after the Confederates overran the fort; the sheer weight of corroborating eyewitness reports, however, whether in letters to family back home, comments made to reporters, or answers to questions in a Congressional inquiry, indicates that an unknown number of Confederate soldiers did indeed commit a number of heinous atrocities against both black and white Federals, some while they were attempting to surrender.

Most accounts, again from those on both sides, indicate that Forrest was not present when the atrocities began and that when he did arrive at the fort he and his officers immediately took steps to restore order and halt the outrages. Confederate Samuel Caldwell, who wrote his wife that the Fort Pillow battle “was decidedly the most horrible sight that I have ever witnessed,” went on to say, “They refused to surrender, which incensed our men and if General Forrest had not run between our men and the Yanks with his pistol and saber drawn not a man would have been spared.” When the battle finally ground to a halt, some 354 Union soldiers had been killed and wounded and the remaining 226 garrison members captured. The Confederates suffered 14 men killed and 76 wounded.

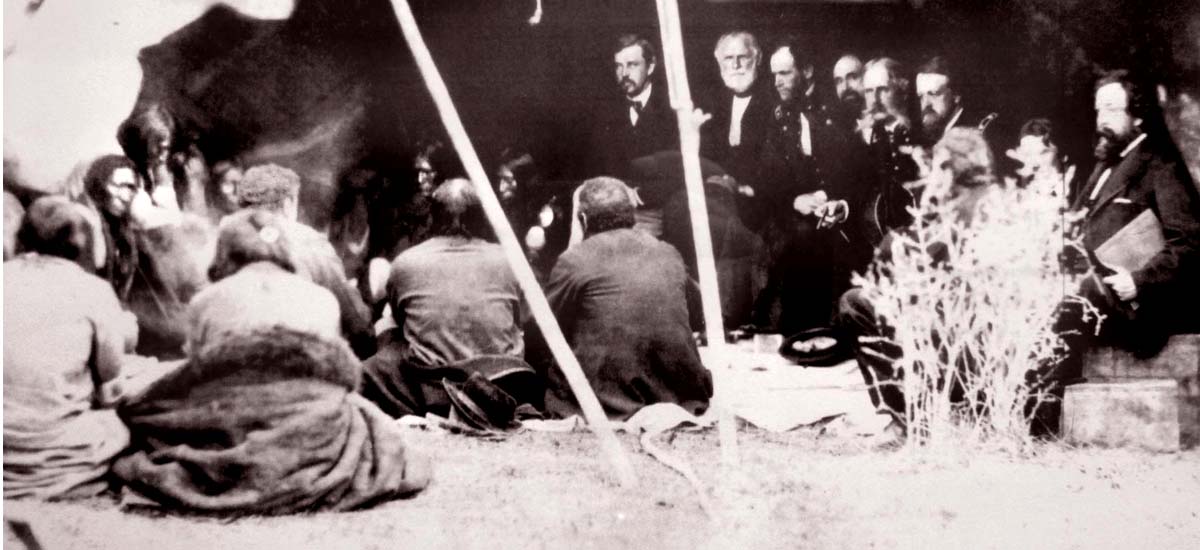

Regarding the surrender demand that Forrest sent into the fort, Captain W.A. Goodman, the bearer, said later he clearly remembered the offer was meant to treat the entire garrison as prisoners “because, when the note was handed to me, there was some discussion about it among the officers present, and it was asked whether it was intended to include the negro soldiers as well as the white; to which both General Forrest and General Chalmers replied, that it was so intended.”

However, other recountings indicate that the Confederates were in no mood to take prisoners. At 8 on the morning after the battle, after the Confederates proposed that the Federals come ashore to remove wounded and assist in burials, U.S. Navy Acting Master William Ferguson landed Silver Cloud below the bluff. He later claimed that he came upon a ghastly scene, finding “about seventy wounded men in the fort and around it, and buried, I should think, one hundred and fifty bodies.”

He later wrote, “All the buildings around the fort and the tents and huts in the fort had been burned by the rebels and among the embers the charred remains of numbers of our soldiers could be seen. Bodies with gaping wounds, some bayoneted through the eyes, some with skulls beaten through, others with hideous wounds … plainly told that but little quarter was shown to our troops. Strewn from the fort to the river bank, in the ravines and hollows, behind logs and under the brush where they had crept for protection from the assassins who pursued them, we found bodies bayoneted, beaten, and shot to death, showing how cold-blooded and persistent was the slaughter.”

Chalmers invited several Federal officers and a newspaper correspondent to visit the fort during the truce. Captain John Woodruff of the 113th Illinois Infantry recounted, “We saw the dead bodies of fifteen negroes, most of them having been shot through the head.”

He later wrote, “Some of them were burned as if by powder around the holes in their heads, which led me to conclude that they were shot at very close range. One of the gunboat officers who accompanied us asked General Chalmers if most of the negroes were not killed after they [the Confederates] had taken possession. Chalmers replied that he thought they had been, and that the men of General Forrest’s command had such a hatred for the armed negro that they could not be restrained from killing the negroes after they had captured them. He said they were not killed by General Forrest’s orders … that both Forrest and he stopped the massacre as soon as they were able to do so. He said it was nothing better that we could expect as long as we persisted in arming the negro.”

This became another point of contention in the battle’s aftermath: the Confederates were firing weapons that used black powder, which was known to leave powder burns when fired from extremely close range, such as when the Confederates swarmed over Fort Pillow’s ramparts.

Grant, for one, was among those Union officers who excoriated the killing and recommended retaliation. He told Sherman, “If our men have been murdered after capture, retaliation must be resorted to promptly.” Sherman, probably the Union’s foremost disciple of hard war, however, saw a default gain for the Union. He wrote, “I know well the animus of the Southern soldiery, and the truth is they cannot be restrained. The result will be of course to make the negroes desperate, and when in turn they commit horrid acts of retaliation we will be relieved of the responsibility.”

Sherman later was quoted as stating that Fort Pillow was one of the unfortunate consequences of war, and Forrest could not be held personally responsible for it. Like Sherman, Maj. Gen. James McPherson, a corps commander in the Union Army of the Tennessee, considered Fort Pillow a Pyrrhic victory for Southern arms. He concluded, “It is a deplorable affair, but will in the end I am certain be most damaging to the rebels.”

The only existing official Confederate reports of the engagement are those prepared by Forrest and Chalmers, neither mentioning anything about a massacre. Both generals asserted that individual Union soldiers, both black and white, who failed to stop firing and drop their weapons caused much of the unnecessary carnage. In considering these statements, it is relevant to examine Forrest’s previous conduct and character in military matters. Less than a month before the Fort Pillow affair, Forrest and his men captured a Union garrison at Union City, but there were no similarities between the treatment of that garrison and what allegedly took place at Fort Pillow.

Forrest was known as a strict disciplinarian, and there are numerous reports of prosecution and punishment of men in his command for such actions as those alleged at Fort Pillow. Indeed, Forrest was known for the fairness and generosity he showed to captured enemy soldiers. He spent the entire war capturing thousands of Union prisoners, and they were almost always immediately paroled through the prisoner exchange program. Forrest often received applause and shouts of appreciation when Union prisoners were read their terms of release and parole.

After Northern newspapers began publishing lurid accounts of the battle—“shocking scenes of savagery” and the “fiendishness of the Confederate behavior”—President Abraham Lincoln was besieged by demands for retaliation. Frederick Douglass, a prominent black leader, asked Lincoln to “order indiscriminate vengeance.” Showing admirable restraint, Lincoln replied, “Once begun, I do not know where such a measure would stop.”

Lincoln faced a quandary. If he exacted Old Testament vengeance, Confederates would continue the cycle of violence by executing white soldiers, something white Northerners would never stand for; if he ignored Southern crimes against black soldiers, he reneged on the government’s obligation to protect all soldiers, black or white, something Lincoln felt very strongly about. In the end, Lincoln and his cabinet essentially did nothing. General Ulysses S. Grant’s spring offensive raised new and more pressing concerns, including huge casualty lists.

Senator Benjamin Wade, a Radical Republican, who from the war’s outset had pressured Lincoln to wage “hard war,” was chairman of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Wade and Representative Daniel Gooch, another Radical Republican, journeyed to Fort Pillow soon after the battle. There they groomed witnesses, asked leading questions, and elevated the responses of illiterate soldiers into statesmanlike prose.

Not surprisingly, the committee concluded, “Southerners treacherously gained the positions from which they assaulted the fort during a flag of truce and then commenced an indiscriminate slaughter, sparing neither age nor sex, white or black, soldier or civilian.” The committee’s ensuing report described Fort Pillow as a “scene of cruelty and murder without a parallel in civilized warfare, which needed but the tomahawk and scalping-knife to exceed the worst atrocities ever committed by savages.”

Wade’s “findings” encouraged Radical Republicans to continue to pressure Lincoln to remove all restraints on the Union war effort. Although a separate Congressional inquiry conducted soon after the battle couldn’t conclusively determine exactly what happened at the fort and concluded that both sides had failed to control the action, Wade’s inquiry made the event “official.”

Congress ordered 40,000 copies of Wade’s report published and distributed in a bound volume just a month after the event to shore up support for the war effort, and it was widely read during the 1864 presidential campaign later that year. Although Sherman conducted an inquiry of his own, and Congress tried again in 1871, neither uncovered any credible evidence to find Forrest culpable. The Congressional inquiry concluded that isolated incidents had taken place along the riverbank and that Forrest had personally halted them when he arrived on the scene. That did little for Forrest and his men; they had already been tried and found guilty in the court of Northern opinion. The stain of the alleged “massacre” would persist through the years and become accepted as fact—even to this day.

Forrest’s association with the post-bellum Ku Klux Klan certainly did nothing to enhance his reputation in the North, though he not only ordered the Klan’s dissolution but also went on to publicly call for social and political advancement for blacks. In the years before his death in 1877, Forrest was clearly a changed man, tired of the race struggle and his reputation as the “Butcher of Fort Pillow.”

Not long before his death—500 blacks attended his funeral—Forrest was invited to speak at a black political gathering. The racial open mindedness that seems to have been growing in him in his later years is clearly evident in the words he spoke that evening: “I came here with the jeers of some white people who think that I am doing wrong…. We have but one flag, one country, let us stand together. Many things have been said about me which are wrong. I have been in the heat of battle when colored men asked me to protect them. I have placed myself between them and the bullets of my men, and told them they should be kept unharmed…. Go to work, be industrious, live honestly, and act truly, and when you are oppressed I’ll come to your relief…. I am with you in heart and in hand.”

I understand the differing points of view today about what happened at Ft. Pillow but one thing is quite certain. The concept of command responsibility was put on display and it failed the test. After the war, Forrest made some efforts to cast himself in a better light. He donated to ex-slave welfare causes and urged loyalty to reunited Union. At this point the whole of the events will never be known but we know from the result that no glory was earned in this battle.