By George A. Larson

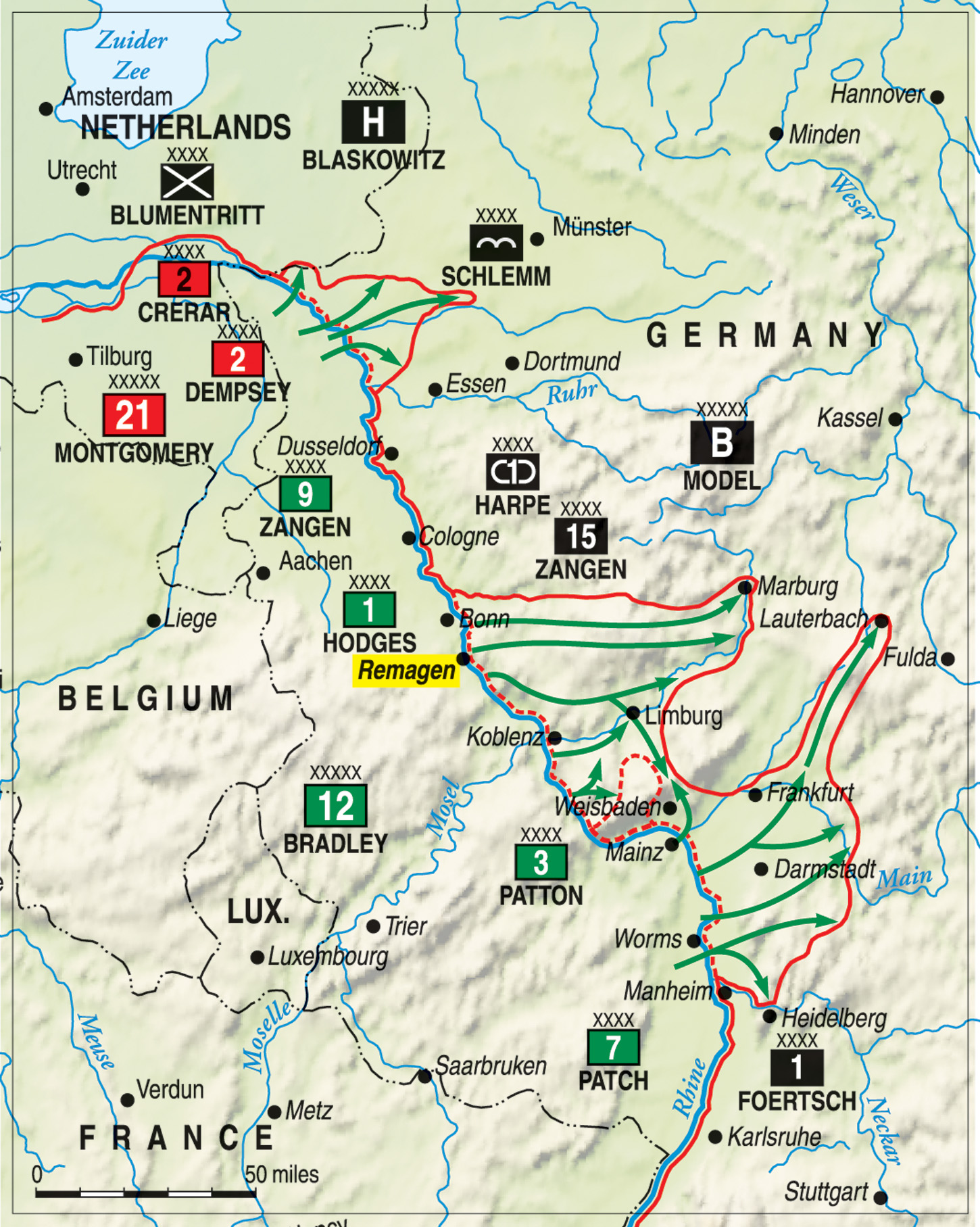

As Allied troops advanced along a broad front toward Nazi Germany in the winter of 1945, the United States Army was eager to capture an intact bridge over the Rhine River to allow its troops and heavy equipment to advance rapidly into Germany. The Rhine was the last major obstacle to Allied forces on their nine-month-long offensive, which had begun on D-Day, June 6, 1944, at Normandy. U.S. aerial reconnaissance identified two bridges still standing over the Rhine. One was at Oberkassel, near Dusseldorf, and the 83rd Division moved forward to seize it. As the American troops approached, German engineers blew up the bridge. The second was just south of Urdingen, and units of the 2nd Armored and 95th Infantry Divisions pushed toward the bridge. The American troops reached and crossed the bridge, but a German counterattack drove them back, allowing their engineers enough time to blow up the bridge. This near loss caused great concern in Berlin, and Adolf Hitler ordered that all remaining bridges over the Rhine be blown up, even if German forces fighting west of the river were cut off from making a last-second escape.

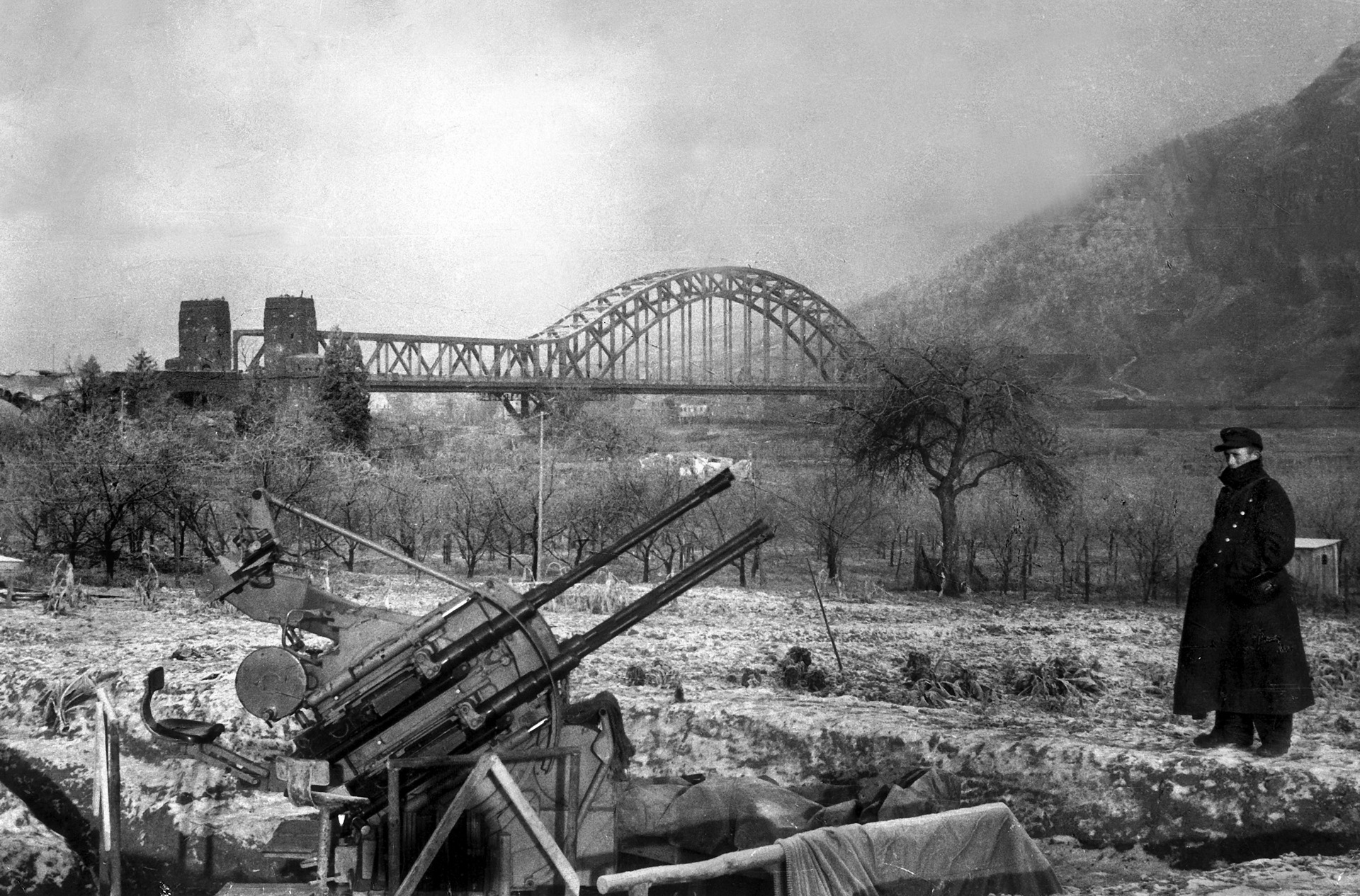

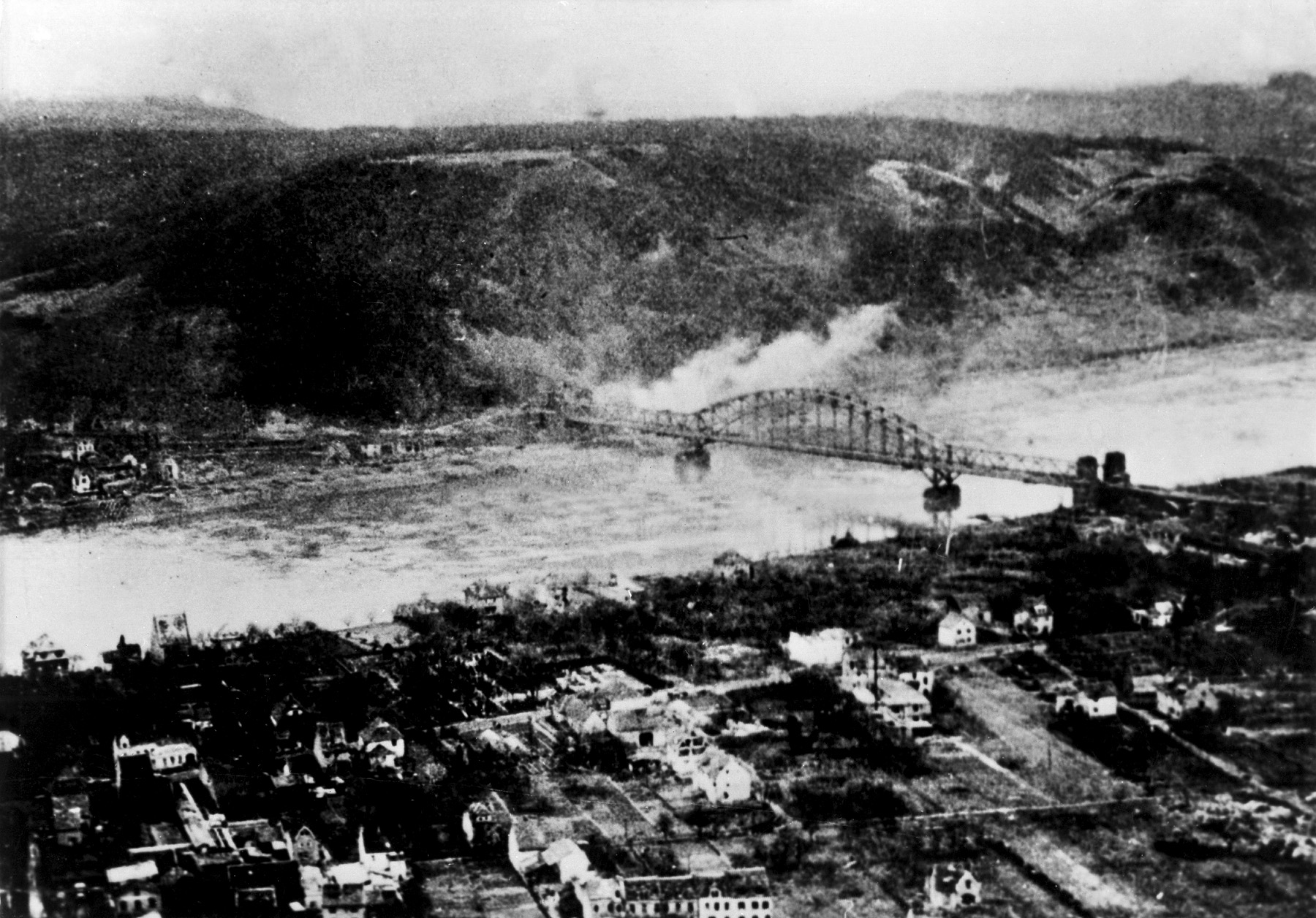

German troops following Hitler’s orders blew up all remaining bridges over the Rhine—except one. Inexplicably, the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen, an ancient, Roman-built town located between Bonn and Koblenz, was left standing. The 1,000-foot-long railroad bridge had been built by German engineers during World War I to move supplies and troops to the Western Front from the armament factories in the Ruhr Valley. After the war, France occupied the area and took control of the bridge. French engineers filled in the demolition chambers with cement, making the bridge very difficult to destroy and increasing its strength.

“Get those Men Moving Into Town”

Remagen, which had been fought over and occupied at one time or another by soldiers from France, Spain, Sweden, and Russia, was a noted resort town. Fine restaurants, cafés, and shops lined the old section of town, which surrounded the four-towered Gothic Church of St. Apollinaris and the remains of the saint, who was martyred in Italy in ad 79. Behind the town rose a 600-foot cliff known as the Erpeler Ley.

The Rhine, flowing swiftly past Remagen, is 300 yards wide; a tributary of the Ahr River adds its turbulent waters to the river’s course a mile above the town. The Ludendorff Bridge, which residents of Remagen resented for ruining the fine view down the Rhine, passed through a 1,200-foot tunnel in the Erpeler Ley before continuing eastward into the Ruhr Valley. The Allies had mounted repeated air attacks against the bridge after the Battle of the Bulge in an effort to slow the movement of German supplies and troops toward Belgium. U.S. air attacks damaged the bridge, but German engineers were able to repair it The bridge was scheduled to be attacked again on the morning of March 7, but the bombing raid was canceled on account of bad weather.

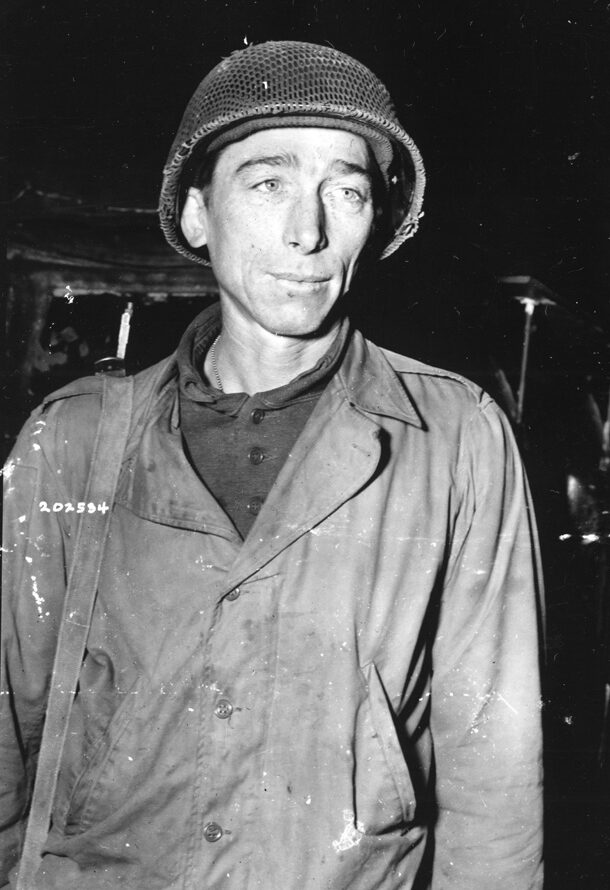

That morning, a reconnaissance unit assigned to the U.S. 9th Armored Division reached Remagen and reported the unbelievable news that the Ludendorff Bridge was still intact and was being used by the Germans. Second Lieutenant Karl Timmermann of the 27th Armored Infantry Regiment, commanding the unit, was half-German himself, the son of an American doughboy from World War I and a German mother. He had been born less than 100 miles from Remagen, at Frankfurt am Main, and emigrated to the United States with his parents as an infant. Leading the scouting party in a jeep, Timmermann rounded a hillside north of Remagen and saw a panorama below that made him blink. The two white-stone supports of the Ludendorff Bridge spanning the blue-green Rhine River were intact. German troops had laid wooden support planks across the bridge’s widely spaced railroad tracks to allow tanks and trucks to cross the bridge to safety. Troops and civilians also jammed the bridge, making it a tempting target for Allied warplanes. Timmermann sent a hasty message back to his battalion commander, Lt. Col. Leonard Engeman, reporting what he had seen.

At noon, Brig. Gen. William M. Hoge, commanding Combat Group B, 9th Armored Division, III Corps, First Army, received verification from Engeman that the Ludendorff Bridge had not been destroyed by the Germans. Against standing orders not to deviate from his planned objective—the town of Ahrweiler—Hoge ordered the bridge to be seized at once. “Get those men moving into town,” he radioed Engeman. “Already on their way,” Engeman answered. He had already ordered Timmermann to take a platoon of Pershing tanks from the 14th Tank Battalion, each equipped with a 90mm main gun, and head straight down the hillside toward the town. Said Engeman, “Go down into town. Get through it as quickly as possible and reach the bridge. The infantry will follow on foot. Their half-tracks will bring up the rear. Let’s make it snappy.”

The Pershing tanks clattered down the winding road into Remagen followed by the infantry. The Americans moved rapidly against spotty resistance from scattered German snipers. German prisoners taken from houses on the outskirts of Remagen were asked about the defenses in the town and on the bridge. One German soldier told the Americans that the Ludendorff Bridge was to be blown up at 4 pm. Similar intelligence had been obtained earlier by troops assigned to the 52nd Armored Infantry Battalion at Sinzig, several miles away from Remagen. These reports were relayed to Hoge, who told Engeman at 3:15 pm, “You’ve got 45 minutes to take the bridge.” Engeman radioed the leading Pershing tank commander, Lieutenant John Grimball: “Get to the bridge as quickly as possible.” Grimball radioed back: “Sir, I am already there.” The Pershing tanks turned to firing positions near the west end of the bridge. One of the first targets they found was a long string of freight cars along the east bank. The Pershings quickly destroyed the train.

German defenders at Remagen were under the command of Captain Willi Bratge, a former schoolteacher who had been given the unenviable task of guarding the vital bridge with a mere handful of wounded, elderly, or conscripted soldiers, some of whom were Russian “volunteers” who had been captured on the Russian front. Bratge had constructed an elaborate system of foxholes and bunkers, but he had only 36 men of mostly low combat efficiency to man them. The bridge itself had been wired with an electric ignition fuse system connected to a control switch inside the entrance to the Erpeler Ley tunnel. Sixty boxes of high explosives had been placed along the structure’s length, ready to be set off at the proper time by combat engineers.

Explosions Near the Remagen

On the morning of the 7th, German Major Hans Scheller was sent to take over the last-ditch defense of Remagen and the destruction of the Ludendorff Bridge. Scheller was totally unfamiliar with the town, the troops, and the bridge itself. He had scarcely arrived in Remagen and presented himself to Bratge when word came that German units on the hill above the town had been attacked by American tanks and infantry. A short while later an artillery captain dashed up to say that his battalion was on its way to the bridge; he pleaded with the other officers not to blow up the bridge before his troops had crossed it. Scheller agreed. He and Bratge established their headquarters inside the mouth of the tunnel on the far side of the bridge and waited for the Americans to show themselves. Precious time was lost. Soon, none was left. The Americans appeared on the opposite bank and began blasting away.

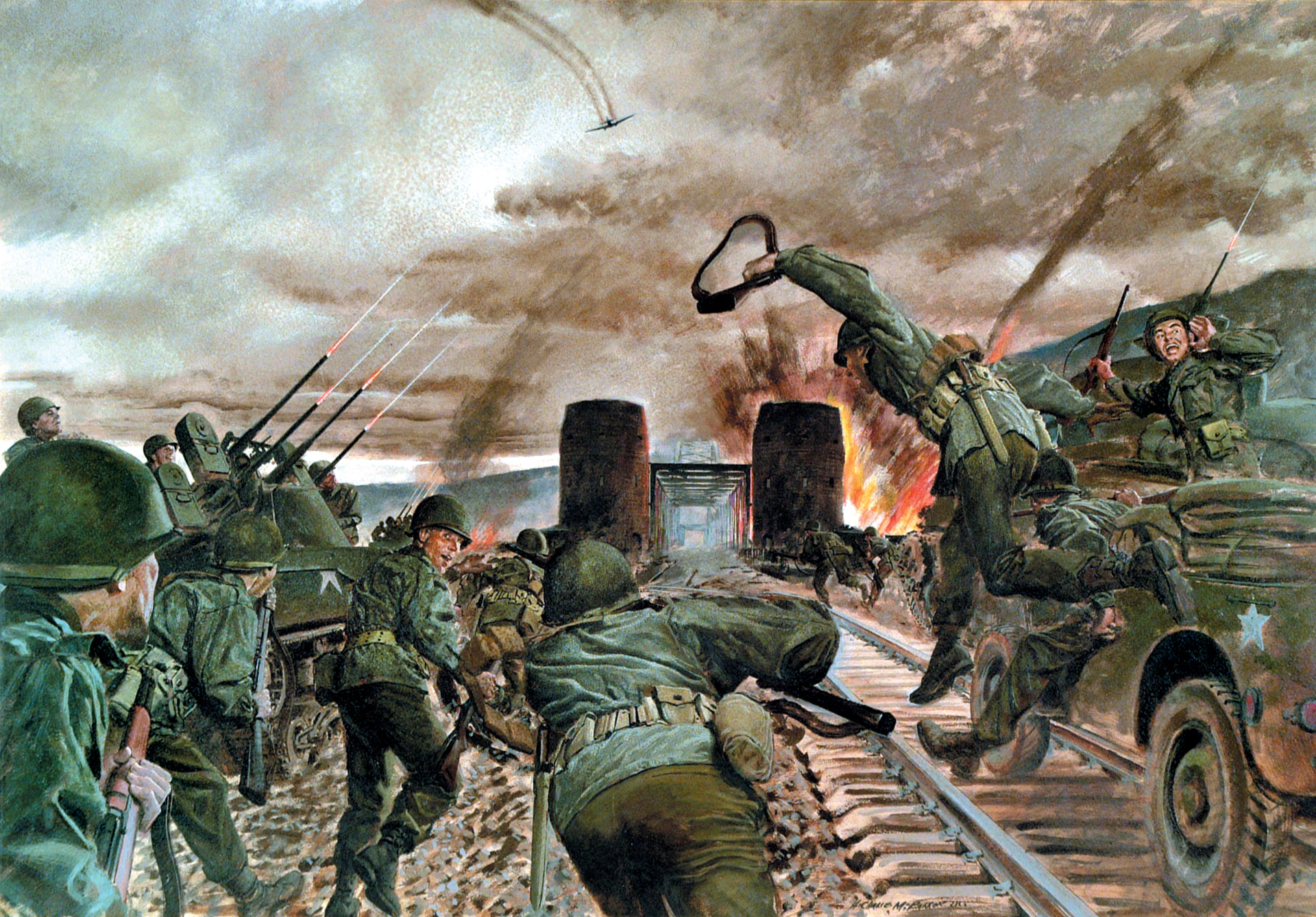

Even though the German defenders of the bridge had waited dangerously long to blow it up, there was no assurance that American troops could make it safely across the bridge before the demolition charges were finally set off. Engeman reasoned that the Germans would probably wait until the American tanks roared onto the bridge before they set off the demolition charges. Infantrymen led by Timmermann moved through the town of Remagen toward the bridge. Meanwhile, Grimball’s Pershing tanks took up firing positions at the bridge’s west end. When the 27th Armored Infantry Regiment’s Company A reached at the west end of the bridge at 3:50 pm, the Germans set off a demolition charge, creating a large crater at the bridge’s approach, preventing the tanks from crossing the bridge. The second detonation went off when Company A was approximately two-thirds across the bridge. The resulting explosion knocked out the main steel diagonal supports located on the upstream side of the bridge and destroyed a section of the wooden planking and flooring, resulting in a six-inch sag to the bridge, but did not destroy the bridge. The Americans, although shaken, continued across.

Paul Priest Recalls Crossing the Rhine

One of the first infantrymen to cross the bridge was Paul Priest of Flint, Michigan. He recalled many years later, “I almost did not make it to the Rhine River, being involuntarily assigned as a replacement crewman in a Sherman tank. I did not like it and after one day asked the captain of the tank unit to let me out, which he did. I was assigned to the division’s headquarters company, performing reconnaissance patrols for the division. On March 5, 1945, two days before we reached the Rhine River, I was detached from the lead division’s reconnaissance group, dropped off at a road checkpoint to guide the division’s vehicles as to which one of three roads to take. I took up my guard post at 2:30 pm. I was told the division should reach my position by 4 to 4:30 pm. The vehicles did not reach me by that time. It kept getting later and later. I went out and picked up all the guns I could locate, creating a large pile near the gas station I decided to use as cover for the evening. These weapons were all over the ground. I recovered them from dead German soldiers in the area, fearing that someone may pick one up and turn it on me.

“I was in the building until 9:30 pm. At that time, I heard the sound of tank tracks coming toward my location. It was the lead column of the 9th Armored Division. I showed the lead tank which road to follow. I climbed onto the lead tank, rejoining my reconnaissance unit in time to make the historic dash across the Ludendorff railway bridge over the Rhine River. On the morning of March 7, I was in the group heading toward the bridge. Not with the lead group of soldiers, but farther back in the reconnaissance column. Our tanks quickly knocked out the German train on the eastern bank. There were many secondary explosions. The tanks first knocked out the engine, bringing the train to a stop in a large cloud of steam released from the destroyed engine.

“I was in the lead group of infantry attacking across the bridge when the tanks had to stop because of the large crater at the west end of the bridge. The demolition charge was set off in front of me. We were taking machine gun fire from the two bridge towers at the east end of the bridge. I was not thinking about anything other than making it safely to the other side of the Rhine River.”

The Pershing tanks provided covering fire for the advancing Company A, 1st Platoon, which was quickly followed by the 2nd and 3rd Platoons. At about the same time, three 9th Armored Division engineers were on the bridge, cutting wires to four-pound demolition charges that had not yet been set off. The engineers were led by Lieutenant Hugh Mott and supported by Staff Sgt. John Reynolds and Sergeant Eugene Dorland. They located the main demolition cable, only to discover that the cable was too thick to be cut with pliers. Mott used his carbine to fire three shots to cut and destroy the demolition cable. Sergeant Joseph DeLisio knocked out the enemy machine gun in one of the east bridge towers and Tech. Sgt. Mike Chinchar knocked out the other. The troops dashed across the bridge. The first U.S. infantryman to make it to the east bank of the Rhine River was Sergeant Alexander Drabik of Toledo, Ohio. He was joined a few seconds later by Timmermann, who thus became the first officer of an invading army to set foot on German soil since Napoleon’s Grande Armée in the early 19th century.

Priest recalled the next part of the crossing: “One of our Pershing tanks, fitted with a bulldozer blade, filled in the crater at the west end of the bridge to allow tanks to move across the bridge. Engineers also were on the bridge to repair the hole in the flooring about two-thirds across the bridge. Once the east bridge tower machine guns were silenced, we cleaned out the tunnel of scattered German troops, young kids, and older men. I helped paint a sign on a piece of wooden planking, nailing it up on the east bank of the bridge: ‘Cross the Rhine with dry feet/courtesy of 9th Armd Div.’ We moved through the railway tunnel, into the cliffs beyond, attacking remaining German 88mm and four 20mm flak guns in that location. Our Pershing tanks destroyed some of the 88mm guns, and the others were abandoned by the German troops, which we destroyed with grenades. We did not encounter any real organized German resistance, for one day, until the Germans brought in more troops.”

Four Scapegoats

With the American infantry dog-trotting across the bridge, the German defenders hunkered inside the darkened railroad tunnel. Scheller attempted to rally the men for a counterattack, but the troops, most of whom did not know who he was, refused to budge. No one wanted to be the last man to die contesting the American entry into Germany. Frustrated, Scheller hopped aboard a bicycle and set off for the rear to get new orders. It was a fatal decision. A few days later, having made his way back to LXVII Corps headquarters at Altwied, Scheller was arrested and court-martialed for deserting his post. Along with three other officers—two engineers and an antiaircraft commander—who had failed to blow up the bridge at Remagen, he was handcuffed, led into the nearby woods, and shot in the back of the neck—four scapegoats for Adolf Hitler’s raging anger at the American bridgehead.

Back at the tunnel, Bratge and the others attempted to exit the opening from the rear, only to find it blocked by enemy GIs. Bratge noticed another group of soldiers and civilians leaving through the front entrance beneath a waving white flag. It gave him the necessary cover to save his honor. “That white flag was raised against our will,” he told the remaining troops. “To continue fighting now would constitute a brazen violation of the Geneva Convention and would make us responsible for the deaths of innocent women and children. For this reason, I order that all fighting cease immediately. Please disable your weapons and, soldiers, be the last to leave the tunnel.” The erstwhile defenders now became captives.

“The Best Break We’ve Had”

The full exploitation of the bridgehead almost did not take place because of a command failure at the highest levels of the American Army. Overall operational planning for offensive troop operations east of the Rhine was under control of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces. Maj. Gen. Harold “Pinky” Bull, in charge of G-3 intelligence, did not want the broad-front plan of advancement to be discontinued. General Omar Bradley, commander of the Twelfth Army Group, telephoned General Dwight Eisenhower, the overall commander of the Allied war effort, with the news that the 9th Armored Division had captured intact the Ludendorff Bridge across the Rhine River and had established a bridgehead on the east bank. Eisenhower told Bradley, “Brad, that’s wonderful. Sure, get right across with everything you’ve got. It’s the best break we’ve had. To hell with the planners.”

Within 24 hours after the Germans failed to destroy the Ludendorff Bridge, 8,000 U.S. troops, large numbers of tanks, self-propelled artillery, and trucks had crossed the Rhine into Nazi-held territory. Everything did not go smoothly. Tanks assigned to Company A, 14th Tank Battalion, made it safely across the bridge, but a tank destroyer assigned to the 656th Tank Destroyer Battalion broke through the wood planking, blocking following vehicles. U.S. troops riding in half-tracks behind the tank climbed out and walked across the bridge. It took some time to clear the stuck vehicle and resume the movement of heavy equipment across the bridge. After the first 24 hours, the German 9th and 11th Panzer Divisions were repositioned around the bridgehead the American forces had established, attempting to isolated the U.S. 9th Armored Division.

On March 9, 10 German Air Force aircraft, eight of which were Stuka dive-bombers, attacked the bridge, scoring two hits. On March 15, a larger force of 20 turbojet aircraft—a mixture of twin turbojet engine Messerchmitt ME-262 fighters and twin turbojet engine Arado AR-234 B-1 bombers—attacked the bridge. They scored no hits. The ubiquitous Priest witnessed the air attacks against the bridge by German aircraft. “This was the first time I saw turbojet aircraft,” he recalled. “At first, I thought the aircraft had been hit from our antiaircraft fire, but the smoke was coming from their twin turbojet engines. They dived from altitude, attacking at a high rate of speed. They were very fast and dropped bombs on the bridge. None of these bombs hit the bridge; [they were] splashing all around the bridge. The Germans were desperately trying to knock out the bridge.”

The German Effort to Blow the Bridge

After Eisenhower ordered the bridgehead to be exploited, American military police on the west bank of the Rhine dealt with a large traffic jam of military vehicles and thousands of infantry. All roads leading to the bridge were crowded, slowing movement across the river. To protect the bridge from German aircraft, flak vehicles were lined up side by side on the west bank, supported by artillery firing across the river at German troops attempting to isolate the 1.5-mile-deep, 1.5-mile-wide American bridgehead. Beginning on March 9, German artillery shelled the bridge and the engineers assigned to the 51st and 291st Engineer Battalions working to repair the bridge. These engineers also constructed pontoon and treadway bridges across the river on either side of the Ludendorff Bridge to increase vehicular traffic and tonnage moving into Germany. They were also a backup against the possibility that the Germans would be able to destroy the main bridge.

The engineers continued to work during heavy German field artillery shelling. Meanwhile, German civilians were removed from Remagen to eliminate the possibility of German troops receiving clandestine reports on what was happening on the west bank and the accuracy of their artillery shelling. American engineer teams worked 24 hours a day to keep the Ludendorff Bridge operational.

The Germans made persistent efforts to destroy the Ludendorff Bridge. They floated a barge containing explosives downstream to blow up the bridge. This was done at night but was not a very well hidden attempt to destroy the bridge. U.S. troops intercepted the barge, preventing it from traveling close enough to the bridge to be ignited and destroy the structure. Mines were floated downstream to blow up the bridge, but American sharpshooters fired at them, blowing them up before they could reach the bridge. Volunteer German troops, putting on rubber suits, entered the icy water upstream, towing explosives behind them to blow up the bridge, but they were detected by American troops on the river’s east bank and killed or captured before they could place the charges.

The Germans tried to make do with the troops and weapons they had along the east bank of the Rhine. The capture of the bridge cut off 300,000 German troops and their equipment west of the river. The German secret weapon, the V-2 rocket, was used against the Ludendorff Bridge. German troops opposite the U.S. east bridgehead pulled back approximately nine miles to get out of possible impact zones. The unit assigned to fire the V-2s against bridge was located at Hellendorn, Netherlands, 130 miles north of Remagen, positioned at that location on March 8. Because of Allied air attacks on its supply lines, the rocket unit suffered fuel and supply problems.

Hitler wanted to fire 50 to 100 V-2s against the bridge to destroy it over a two-day span, but the rocket troops were only able to fire 11 V-2s against the bridge on March 17. The rockets came dangerously close to the bridge. One struck the ground near the Apollinaris church in the town of Remagen, one mile from the bridge. The rocket destroyed several buildings around the church, with blast damage reaching out approximately 3,000 feet. The resulting ground and air shock wave was felt throughout the town. Another V-2 splashed into the Rhine, one mile from the bridge. A third landed inside the town of Remagen, destroying a building where 12 U.S. troops were billeted, killing three. A fourth V-2 struck the command post of the U.S. Army 1159 Engineer Combat Group, killing three and injuring 31.

The Bridge Finally Collapses

Even though none of the rockets hit the bridge, the ground shock wave effects, along with the demolition explosion and constant U.S. military traffic on the bridge, eventually caused it to collapse. At 3 pm on March 17, the bridge fell into the Rhine River, killing 28 American engineers who were working on the bridge. Recalled Priest, “I was not in the area when the bridge collapsed from the volley of V-2 rockets. We had moved up into the hills, up through a gully. This was where I was shot by a German using a wooden bullet. The impact took my helmet off. I was kept in the line, the wound considered only a flesh wound. Fortunately, by the time the bridge collapsed, the pontoon bridges took up the burden of moving men and equipment across the Rhine. The bridge was a mass of twisted metal, visible near both the west and east banks of the Rhine River. When I left the United States, I brought with me a small foldout camera, [and I took] photographs as we moved from place to place. I also took photographs from German troops we encountered and disarmed during the search.

“As we moved away from the Rhine River, many German troops surrendered to us. They threw their weapons onto the ground, raised their hands into the air, and surrendered. I did not take part in any large actions after crossing the Rhine River. German troops gave up, surrendering to U.S. or British troops rather than to the Soviet Army troops farther to the east. It was at this time I found out my parents had received a telegram reporting my death in Germany. It was another Paul Priest. But things like that happen in war. It was a great relief to my parents when they heard I was still alive when they got a letter from me.”

Priest survived the war and returned to Flint, where he married his prewar sweetheart, Joan. The couple had three children. After the war, Priest worked as a carpet and tile installer, eventually moving to Deadwood and then to Box Elder, South Dakota. As for his fellow GIs at Remagen, a shower of medals fell on their chests. Thirteen soldiers, including Timmermann, DeLisio, Drabik, Grimball, Mott, and Chinchar, received the Distinguished Service Cross. Another 152 received the Silver Star. The units that composed Combat Command B of the 9th Armored Division were awarded Presidential Unit Citations. Army Chief of Staff George Marshall summed up the significance of Remagen: “The prompt seizure and exploitation of the crossing demonstrated American initiative and adaptability at its best, from the daring action of the platoon leader to the Army commander who quickly directed all his moving columns,” said Marshall. “The bridgehead provided a serious threat to the heart of Germany, a diversion of incalculable value. It became a springboard for the final offensive to come.”

Karl Timmermann, the first Allied officer across the Rhine, returned to his hometown of West Point, Nebraska, after the war. He arrived without fanfare, alighting from a train and walking into town with his barracks bag slung across his shoulder. His welcoming committee consisted of one small dog that nipped at his heels. Timmermann ignored the dog. He had seen far worse at Remagen.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments